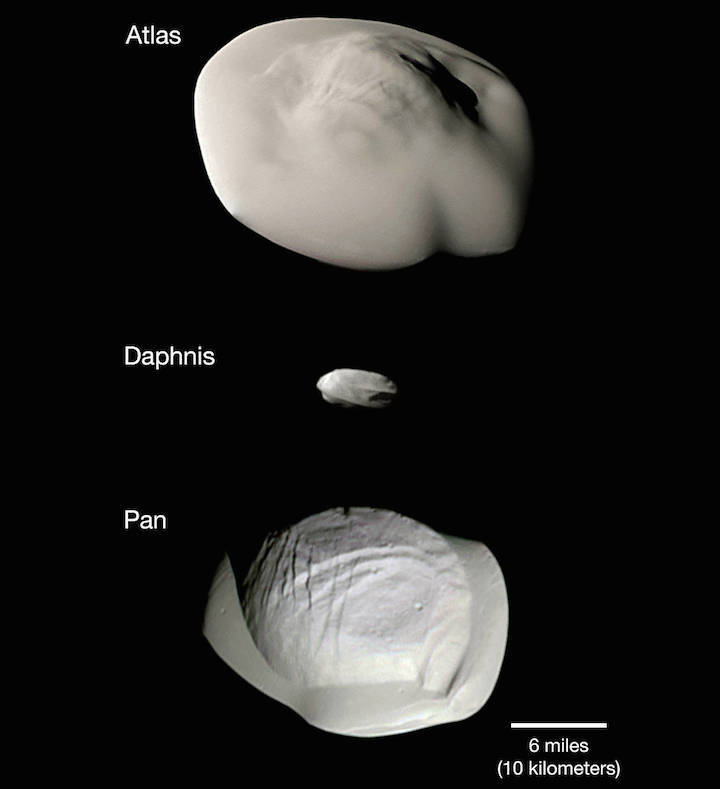

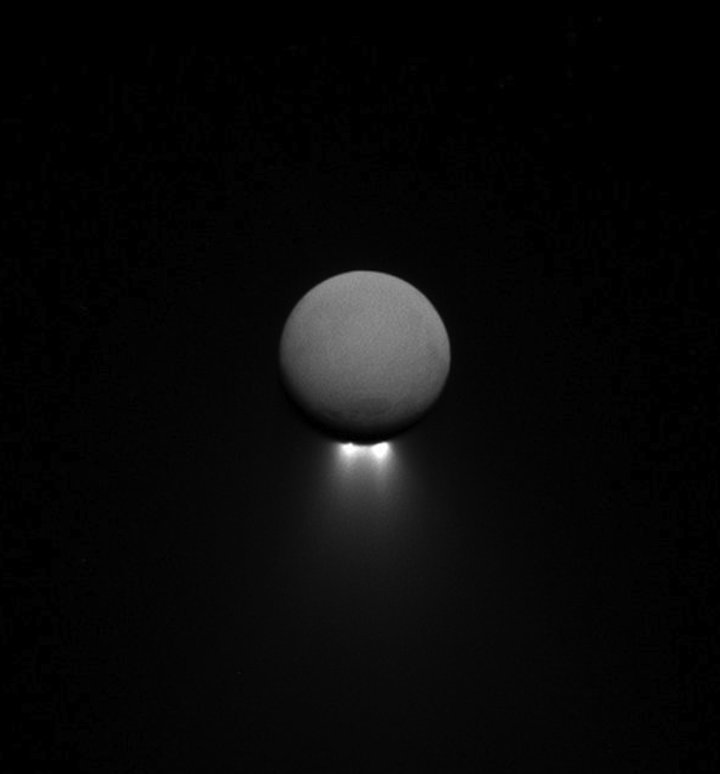

A photo of Saturn's moon Enceladus looks poised for liftoff as jets fly from its southern hemisphere.

While Enceladus can't fly — at least outside of its ordinary orbit around the ringed planet — its remarkable icy jets intrigue scientists because they hint at a subsurface ocean that could support life.

The photo, taken by the Cassini spacecraft, spotlights the moon's Saturn-facing hemisphere, which is 313 miles across (504 km), according to NASA's image caption. The jets are backlit by sunlight, while the front shines with light reflected back from Saturn. Cassini was 502,000 miles (808,000 km) from Enceladus when it captured the visible-light image with its narrow-angle camera on April 13, and the image shows 3 miles (5 km) per pixel.

Enceladus' fierce jets emerge from a series of ridges in its southern hemisphere nicknamed "tiger stripes." Cassini first spotted the jets in 2005, and dove through the plumes multiple times; in 2015, it passed within 30 miles(50 km) of the moon's surface while sampling their composition. Data from that flyby suggested that its subsurface ocean might have enough energy, suggested by the existence of molecular hydrogen, to host life similar to microbes on Earth. Besides water ice, the plumes contain traces of methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, salts and simple organic molecules.

Cassini is a collaboration among NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency, and it has orbited Saturn since 2004. The probe is in the Grand Finale phase of its mission, as it makes close flybys between Saturn and its rings before plunging down into the planet's atmosphere Sept. 15. That dive is partially motivated by a desire to protect the little icy moon — as Cassini ran out of fuel, its orbit could have become unstable and led to it crashing and contaminating moons in Saturn's neighborhood.

Quelle: SC

---

Update: 25.07.2017

.

As NASA's Cassini spacecraft makes its unprecedented series of weekly dives between Saturn and its rings, scientists are finding -- so far -- that the planet's magnetic field has no discernible tilt. This surprising observation, which means the true length of Saturn's day is still unknown, is just one of several early insights from the final phase of Cassini's mission, known as the Grand Finale.

Other recent science highlights include promising hints about the structure and composition of the icy rings, along with high-resolution images of the rings and Saturn's atmosphere.

Cassini is now in the 15th of 22 weekly orbits that pass through the narrow gap between Saturn and its rings. The spacecraft began its finale on April 26 and will continue its dives until Sept. 15, when it will make a mission-ending plunge into Saturn's atmosphere.

"Cassini is performing beautifully in the final leg of its long journey," said Cassini Project Manager Earl Maize at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. "Its observations continue to surprise and delight as we squeeze out every last bit of science that we can get."

Cassini scientists are thrilled as well -- and surprised in some cases -- with the observations being made by the spacecraft in the finale. "The data we are seeing from Cassini's Grand Finale are every bit as exciting as we hoped, although we are still deep in the process of working out what they are telling us about Saturn and its rings," said Cassini Project Scientist Linda Spilker at JPL.

Early Magnetic Field Analysis

Based on data collected by Cassini's magnetometer instrument, Saturn's magnetic field appears to be surprisingly well-aligned with the planet's rotation axis. The tilt is much smaller than 0.06 degrees -- which is the lower limit the spacecraft's magnetometer data placed on the value prior to the start of the Grand Finale.

This observation is at odds with scientists' theoretical understanding of how magnetic fields are generated. Planetary magnetic fields are understood to require some degree of tilt to sustain currents flowing through the liquid metal deep inside the planets (in Saturn's case, thought to be liquid metallic hydrogen). With no tilt, the currents would eventually subside and the field would disappear.

Any tilt to the magnetic field would make the daily wobble of the planet's deep interior observable, thus revealing the true length of Saturn's day, which has so far proven elusive.

"The tilt seems to be much smaller than we had previously estimated and quite challenging to explain," said Michele Dougherty, Cassini magnetometer investigation lead at Imperial College, London. "We have not been able to resolve the length of day at Saturn so far, but we're still working on it."

The lack of a tilt may eventually be rectified with further data. Dougherty and her team believe some aspect of the planet's deep atmosphere might be masking the true internal magnetic field. The team will continue to collect and analyze data for the remainder of the mission, including during the final plunge into Saturn.

The magnetometer data will also be evaluated in concert with Cassini's measurements of Saturn's gravity field collected during the Grand Finale. Early analysis of the gravity data collected so far shows discrepancies compared with parts of the leading models of Saturn's interior, suggesting something unexpected about the planet's structure is awaiting discovery.

Sampling Saturn

In addition to its investigation of the planet's interior, Cassini has now obtained the first-ever samples of the planet's atmosphere and main rings, which promise new insights about their composition and structure. The spacecraft's cosmic dust analyzer (CDA) instrument has collected many nanometer-size ring particles while flying through the planet-ring gap, while its ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) has sniffed the outermost atmosphere, called the exosphere.

During Cassini's first dive through the gap on April 26, the spacecraft was oriented so its large, saucer-shaped antenna would act as a shield against oncoming ring particles that might cause damage. While at first it appeared that there were essentially no particles in the gap, scientists later determined the particles there are very small and could be detected using the CDA instrument.

The cosmic dust analyzer was later allowed to peek out from behind the antenna during Cassini's third of four passes through the innermost of Saturn's main rings, the D ring, on June 29. During Cassini's first two passes through the inner D ring, the particle environment there was found to be benign. This prompted mission controllers to relax the shielding requirement for one orbit, in hopes of capturing ring particles there using CDA. As the spacecraft passed through the ring, the CDA instrument successfully captured some of the tiniest particles there, which the team expects will provide significant information about their composition.

During the spacecraft's final five orbits, as well as it final plunge, the INMS instrument will obtain samples deeper down in the atmosphere. Cassini will skim through the outer atmosphere during these passes, and INMS is expected to send particularly important data on the composition of Saturn's atmosphere during the final plunge.

Amazing Images

Not to be outdone, Cassini's imaging cameras have been hard at work, returning some of the highest-resolution views of the rings and planet they have ever obtained. For example, close-up views of Saturn's C ring -- which features mysterious bright bands called plateaus -- reveal surprisingly different textures in neighboring sections of the ring. The plateaus appear to have a streaky texture, whereas adjacent regions appear clumpy or have no obvious structure at all. Ring scientists believe the new level of detail may shed light on why the plateaus are there, and what is different about the particles in them.

On two of Cassini's close passes over Saturn, on April 26 and June 29, the cameras captured ultra-close views of the cloudscape racing past, showing the planet from closer than ever before. Imaging scientists have combined images from these dives into two new image mosaics and a movie sequence. (Specifically, the previously released April 26 movie was updated to greatly enhance its contrast and sharpness.)

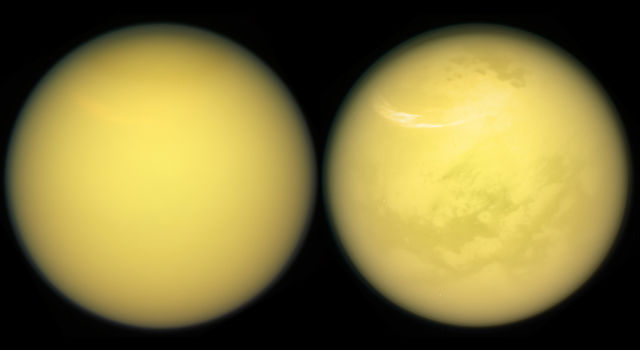

Launched in 1997, Cassini has orbited Saturn since arriving in 2004 for an up-close study of the planet, its rings and moons, and its vast magnetosphere. Cassini has made numerous dramatic discoveries, including a global ocean with indications of hydrothermal activity within the moon Enceladus, and liquid methane seas on another moon, Titan.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. JPL designed, developed and assembled the Cassini orbiter.

Quelle: NASA

---

Update: 1.08.2017

.

Saturn Surprises Right Up Until Cassini’s End

Saturn keeps its secrets as NASA's Cassini spacecraft heads towards its September grand finale.

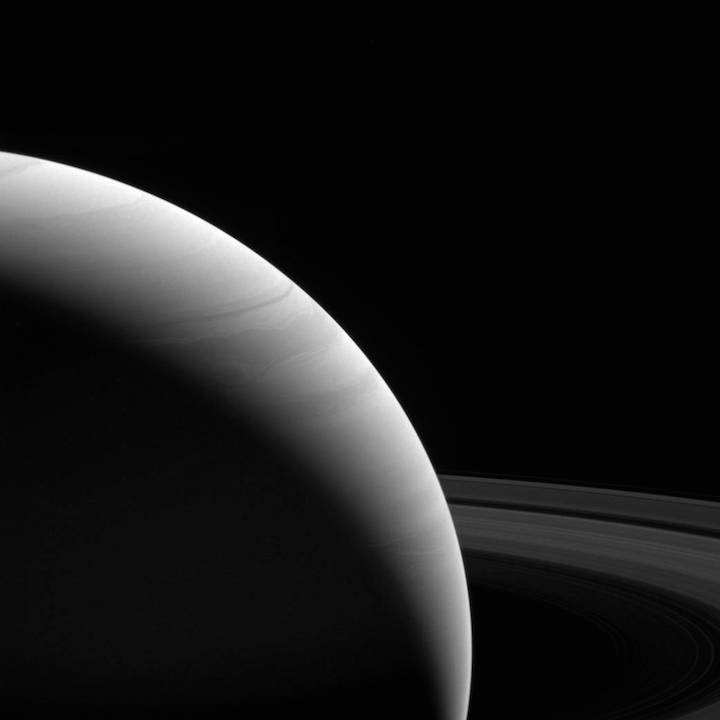

An alien vista stretches out before Cassini, in this false color image taken by the spacecraft's narrow angle camera on July 16th. You can just see the thin haze of the planet's upper atmosphere on the lit limb, with the rings beyond.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The ringed planet seems to be hanging on to at least some of its secrets right up until the very end.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft is now in the midst of a series of dramatic weekly Grand Finale dives through the gap between Saturn and its ring system. This follows a series of wider Ring Grazing Orbits spanning late 2016 into earlier this year, and will climax with the end of the mission itself in September.

Cassini is performing beautifully in the final leg of its long journey," says Earl Maize (NASA-JPL) in a recent press release. "Its observations continue to surprise and delight as we squeeze out every last bit of science that we can get."

Cassini is now in the 16th of a total of 22 weekly orbits, coming as close as 1,900 miles to the planet's cloud tops. This allows the mission to not only examine the magnetic field of the planet close up, but also allows Cassini a chance to sample the upper atmosphere of the planet itself.

These final orbits are a bit of a risk, as the spacecraft must thread its way through the ring plane at 77,000 mph. This elevated risk is one reason that researchers have held off on the exploration of Saturn close-up until now.

A "noodle mosaic" of Saturn, composed of 137 images from the first Grand Finale dive in April, shows the pole (upper left) down to the planet's equator (bottom right).

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute

Science at Saturn

One of the strangest recent findings from Cassini is what it didn't find: much of a discernible difference in tilt between Saturn's rotational axis and its magnetic field. In other planets, this tilt sustains the dynamos that emanate from liquid metal cores. Think of Earth, where liquid iron in its outer core generates our protective magnetic field — and a magnetic pole offset from Earth's true, rotational pole.

Cassini's magnetometer has found that Saturn's magnetic pole — in this case, generated by liquid metallic hydrogen in its core — is remarkably well aligned with the planet's rotational axis, down to less than 0.06 degrees. This finding flies in the face of how we think planetary magnetic fields are generated, suggesting that we don't understand Saturn's internal structure as well as we thought we did.

The surprisingly good alignment also masks the true length of Saturn's day. While we see the planet's cloud tops spinning once every 10 hours, 14 minutes near the planet's equator, a gaseous planet doesn't all rotate at the same rate so its rotation changes at the poles. A discernible tilt in the magnetic field would make the planet wobble, betraying its true rotational speed. Since scientists haven't been able to measure the wobble, the length of Saturn's day remains a mystery.

Plus, check out these amazing new views of aurora over the limb of Saturn, shot by Cassini on July 20, 2017:

Taking Samples of Saturn

On the first plunge through the ring plane, Cassini went “dish first,” using its large radio antenna to protect the bulk of the spacecraft while a few instruments made tentative peeks out around the edges to "sniff" the local environment. But as researchers discovered the gap between the planet and the rings is — at least where Cassini sampled it — surprisingly devoid of debris, engineers relaxed constraints somewhat on subsequent passages, bringing other instruments to bear. Cassini has since used its Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) to sample the tenuous exosphere of Saturn's atmosphere and its Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA) to sample the few ring particles obtained on each pass.

The strange "streaky texture" of Saturn's C-ring.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

What's next? Cassini will dive deeper still on final passes and the INMS is expected to get better atmospheric samples on each pass. And of course, we've getting some thrilling up close images of Saturn itself, with more to come.

Launched two decades ago in 1997, the Cassini mission promises a thrill ride to the very last moment, just over one month away. Cassini is on a ballistic date with destiny, meaning that even if the spacecraft were to fall silent, destruction via atmospheric entry on September 15th is assured. But the science results will continue to pay off for years to come.

Not bad for a spacecraft launched last century.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope

---

Update: 10.08.2017

.