In 2015, Congress extended NASA’s operations of the International Space Station through 2024 — but as that deadline approaches, lawmakers are trying to figure what should happen to the orbiting lab beyond that date. This morning, the House Subcommittee on Space held a hearing to discuss just that, and one thing is clear: there’s no consensus yet.

A variety of suggestions came up at the hearing, and most of them focus on transitioning the ISS from NASA to the private space industry at some point. But it’s uncertain how that transition should happen and when commercial companies will be ready to fully take over the ISS without NASA’s help.

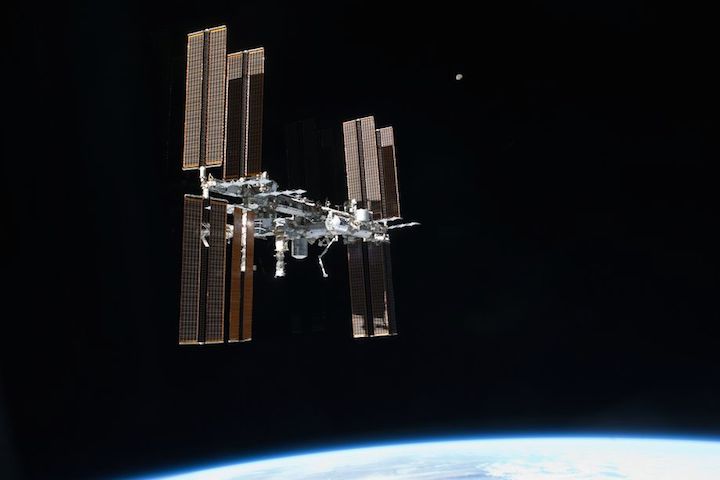

The ISS has been a global collaborative project between NASA and space agencies from Russia, Japan, the European Union, and Canada. Since 2000, the ISS has been the primary destination for NASA astronauts traveling to space. The lab, which sits in lower Earth orbit, has been a place for conducting valuable scientific research in microgravity, including testing materials and researching new drugs. It’s also been a tool to learn more about how zero gravity affects the human body — insights that will be needed for sending humans to Mars one day.

It costs NASA between $3 and $4 billion to operate its share of the ISS each year —about half of the agency’s budget for human space exploration. But as NASA moves forward with its more ambitious goals for the future — namely sending humans into deep space and onto Mars — there’s a concern about how money within the agency will be distributed.

NASA is currently developing a monster rocket called the Space Launch System, as well as a crew capsule called the Orion. Together, those two programs take up about $4 billion of NASA’s annual budget. But a whole lot more hardware will have to be developed if we want to get people to the surface of another world; we need habitats, landers, and a bunch of other technology we haven’t even created yet.

At today’s hearing, Rep. Brian Babin (R-TX), the chairman of the space subcommittee, noted that continuing to operate the ISS would mean trade-offs at NASA. “Tax-dollars spent on the ISS will not be spent on destinations beyond low Earth orbit, including the Moon and Mars,” Babin said in his opening statement. “What opportunities will we miss if we maintain the status quo?”

During the Obama administration, NASA made it clear that it wanted to eventually move beyond lower Earth orbit and transition the ISS to the private sector. However, it’s unlikely that commercial space companies will be fully prepared to privatize the ISS by 2024. That means operating the ISS with private dollars and personnel, as well as using commercial launch vehicles to send people and cargo to and from the station.

At the hearing, Eric Stallmer, the president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, argued that the best way to transition the ISS would be to extend the station’s operations through 2028, while opening up even more opportunities for private companies to partner with NASA. The space agency has already tasked private companies with figuring out ways to send people and supplies to and from the ISS. There are even plans to allow companies to hook up their own modules. But that’s not enough, according to Stallmer. NASA should begin privatizing portions of the station and adding even more commercial habitats to the ISS, he said.

Stallmer’s idea was approved by Mary Lynne Dittmar, the executive director for the Coalition for Deep Space, but she also argued that the only way the transition will work is if there are multiple ways to make revenue off of the station. Yet the industry is still quite young, and it’s not clear what kind of commercial markets will emerge in lower Earth orbit, said Dittmar.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8205501/29894260842_1d70c6d562_o.jpg)

No one explicitly called for the complete cancellation of the ISS, though the prospect hung over most of the witnesses’ testimonies today. Everyone seemed to agree that losing the station would be detrimental — both for NASA and the commercial space industry. Private companies use the station to test out new vehicles and develop new technologies; Stallmer said that the industry would “lose its outpost in space” without the ISS. NASA has spent $67 billion on the station’s development to date and is still learning things from using the lab, according to Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration.

“It’s... wrong to assume that ISS and exploration are competing with each other,” Gerstenmaier said at the hearing. “They’re really helping each other. We’re working today on space station to understand the physiological problems of being in microgravity on the human body. Those are not fully resolved yet.”

The ISS also provides NASA with a relatively close destination for astronauts and cargo, which are sent them on over a dozen missions every year. NASA plans to eventually build another outpost in the space around the Moon, but that reality is many years away still. Even when that station is completed, NASA’s Space Launch System will only be able to launch people and cargo there once or twice a year at best.

Plus, the idea of completely getting rid of the ISS is troubling for Congress, given China’s ambitions in space. In 2023, the Chinese space agency plans to put up its own space station capable of housing six astronauts. Congress members, which often view China’s spaceflight initiatives as threatening US leadership in space, expressed concern that abandoning the ISS would mean “turning over human presence in low-Earth orbit to China,” according to Babin.

For now, there’s no clear answer about the path forward. However, NASA is going to have to come up with some kind of roadmap soon. Yesterday, President Donald Trump signed into law the NASA Transition Authorization Act of 2017, which also directs the agency to come up with a plan for transitioning the ISS beyond 2024. And in the world of space, 2024 is only a heartbeat away.

Quelle: THE VERGE