When leaders of the Congressional committees that approve NASA’s missions and budgets put forth their priorities in February, only space science and deep space exploration made the cut. Conspicuously absent was Earth science—a US $2 billion function within NASA that tracks our rapidly changing “home planet.”

Add in White House skepticism of climate science, and what experts call today’s “golden age” of monitoring Earth via satellite faces some serious challenges.

That age began in 2009, when President Barack Obama responded to a U.S. National Research Council warning that budget cuts had left the United States’ Earth observing system “at risk of collapse.” NASA, the lead federal agency for satellite development, saw its Earth science budget rise 56 percent between 2008 and 2016, and it placed eight new Earth-observing satellites in orbit during that period packing state-of-the-art sensors.

The data they deliver inform a widening range of activities—crop planning and management, wildfire risk assessment, extreme air pollution warnings, and more. NASA delivered 1.42 billion data products in 2015—174 times as many as it delivered in 2000—according to a November 2016 review by the agency’s Inspector General.

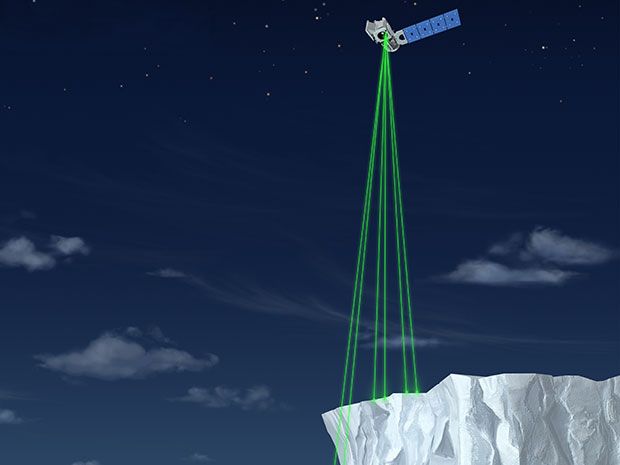

More missions are in the pipeline, such as NASA’s second Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat-2), whose primary objectives are tracking melting polar ice sheets and glaciers and quantifying the carbon locked up in the globe’s forests.

ICESat-2, however, exemplifies both the present strength of the U.S. Earth observation program and a less visible weakness. To understand why, you need a sense of the ambitious nature of ICESat-2’s mission.

Rather than rerunning the first ICESat mission, which ended in 2009, NASA redesigned the laser altimeter to boost its impact. One laser beam firing sporadically became six beams firing 365 days a year; higher-precision digital photon counting replaced analog detection of beams bouncing back from Earth.

ICESat-2 should enable measurement of annual elevation changes in ice sheets at ± 4-millimeter accuracy (and better for other targets), and at 17 times the spatial resolution of its predecessor, according to Thorsten Markus, chief of cryospheric sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in Maryland. Such data, he says, will elucidate some basic physical processes that elude climate models, and thus improve their predictions.

But pushing for the best has not come cheap. Instead of $300 million for an ICESat rerun, NASA’s estimate for ICESat-2’s development started at $559 million and has grown to $764 million. Including operations for up to seven years, the mission could cost nearly $1.1 billion, according to that November Inspector General report. Launch dates, meanwhile, have slipped from 2015 to 2018.

Delays and cost creep in ICESat-2 and other missions, as well as several failed launches, put a significant tarnish on Earth observation’s golden age. Extending existing missions to avoid gaps in observational data creates risk, according to NASA’s Inspector General: “More than half the Agency’s 16 operating missions have surpassed their designed lifespan and are increasingly prone to failures that could result in critical data loss….”

Similar risks confront the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a key partner in climate and weather observation, according to a February report by Congress’s watchdog agency the Government Accountability OfficeNOAA’s polar readings currently come from a dying NASA demonstration mission. If it fails before the agencies’ long-awaited Joint Polar Satellite System launches, it would degrade weather forecasts, “exposing the nation to a 15 percent chance of missing an extreme weather event forecast,” writes the GAO.

If the golden age of Earth observation harbored weak spots before the 2016 election, experts say the new administration introduces new risks. One is the $54 billion in belt-tightening proposed for federal agencies by President Donald Trump. In early March the Washington Post reported that the President will ask for 17 percent less funding for NOAA.

Another is potential interference with climate science. In February, Lamar Smith, chairman of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, called for “rebalancing” of NASA’s portfolio. A former chairman, Robert Walker, now a lobbyist for space-related industries, built a similar plank into the space platform that he drafted for Trump’s campaign. Both men question human-induced climate change—a view held by many Republicans in Congress and Trump appointees.

Walker says expanded Earth observation under Obama came at the expense of other science programs, particularly deep space robotic missions. He also alleges that NASA science was “tainted" by a political agenda against fossil fuels, focusing on impacts from burning coal, oil, and natural gas and neglecting natural climate influences such as volcanic eruptions. “There’s an extremely complex system that involves a lot more than CO2,” he says.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2014 assessment, however, expressed “very high confidence” that volcanic eruptions caused only “a small fraction” of the warming observed since the Industrial Revolution. And it cites “robust evidence” from satellite data showing that natural factors have had “near-zero” effect since 1980.

The notion that human activities alter climate is not a political invention, but a scientific judgement based on gigabytes of data downloaded daily from a gilded era’s orbiting sensors. “It’s not a belief,” says NASA’s Markus. “That’s what the data show.”

Quelle: IEEE