Sunday’s mission will be the second SpaceX launch from historic Pad 39A. Since the end of the Space Shuttle era, the pad has been extensively refurbished, including the construction of a Horizontal Integration Facility (HIF) for Upgraded Falcon 9 vehicles and payloads. Photo Credit: SpaceX

Just three weeks after triumphantly bringing historic Pad 39A back to operational service, SpaceX is set to launch the heavyweight EchoStar-23 communications satellite, in the hours of darkness on Tuesday, 14 March. The Hawthorne, Calif.-based launch services organization’s Upgraded Falcon 9 booster was originally scheduled to fly early on Sunday, 12 March, which might have seen it fly during the middle-of-the-night crossover period from Eastern Standard Time (EST) to Eastern Daylight Time (EDT). However, a delayed Static Fire Test of the nine Merlin 1D+ first-stage engines—which eventually took place on the evening of Thursday, 9 March, some 48 hours later than planned—led SpaceX to move the revised launch time up to a 2.5-hour “window”, which extends from 1:34 a.m. through 4:04 a.m. EDT on Tuesday. This promises to be the first nocturnal launch from Pad 39A since shuttle Discovery’s second-to-last mission, STS-131, way back in April 2010.

The nature of its EchoStar-23 primary payload—destined for insertion into an approximately 22,300-mile (35,800 km) Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO)—has led to a decision for the Upgraded Falcon 9’s first stage to be discarded on this flight. The high-energy and high-velocity demands for the GTO destination has long precluded the possibility of bringing first stages back to solid ground at Landing Zone (LZ)-1 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla. It is noted the greater energy demands to lift heavyweight payloads into such high orbits invariably means that less propellant can be kept in reserve for the critical engine “burns” needed to steer the first stage back through the sensible atmosphere to achieve a pinpoint landing on solid ground. However, several previous GTO-bound SpaceX missions, including last August’s JCSAT-16, have completed landings on the Autonomous Spaceport Drone Ship (ASDS) without incident. In comments provided to AmericaSpace, SpaceX explained that several reasons, including the size and mass of the payload and the complexity of the orbital parameters, were behind the decision to dispense with a landing attempt on this mission.

The Upgraded Falcon 9’s nine Merlin 1D+ first-stage engines roar to full power during Thursday evening’s Static Fire Test. Photo Credit: SpaceX/Twitter

It has been a busy few months for Inverness, Colo.-headquartered EchoStar Corp., which saw its EchoStar-18 bird lofted via Europe’s Ariane 5 booster in June 2016 and EchoStar-19 following aboard a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V, a few days before Christmas. Another mission, EchoStar-21—tasked with providing pan-European mobile broadband services, together with S-band support for EchoStar Mobile Ltd.—was scheduled to ride a Russian Proton-M vehicle out of the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan in December 2016, but has been repeatedly postponed and is now slated to fly no sooner than April. Additionally, later in 2017, SpaceX will launch the SES-11 satellite into the 105 degrees West orbital position, marketing its transponders as EchoStar-105.

These launches add to an impressive portfolio of satellites for a company which was formed in 1980, originally as a distributor for C-band television systems. EchoStar received a Direct Broadcast Satellite (DBS) license at 119 degrees West longitude in 1992. Three years later, in December 1995, its first satellite—EchoStar-I—was launched atop a Chinese Long March 2E booster and shortly afterwards the company began marketing its home satellite TV system, branded “Dish Network”. Although the next two EchoStar satellites, launched in 1996 and 1997, encountered major failures, subsequent missions atop Proton, Atlas, Zenit, and Ariane rockets went on to provide communications services across the contiguous United States, as well as Alaska and Hawaii, together with Bermuda, Mexico, Puerto Rico and other locations. By the time EchoStar-XVIII launched atop an Ariane 5 booster in June 2016, Dish Network had accrued almost 14 million subscribers for its pay-TV services.

EchoStar-23 has been built by Space Systems/Loral (SS/L), based upon its highly reliable SSL-1300 “bus”, which in 2015 recorded 100 of these satellites launched into orbit. There are, of course, major differences between that centenery of satellites. Compared to the first-flown member of the fleet—Japan’s Superbird-A communications satellite, launched in June 1989—today’s SSL-1300 bus produces eight times more power, a 30-percent longer operational life span and can house four times as many transponders. SS/L was selected in April 2014 to build EchoStar-23, which is described as “a very flexible Ku-band satellite, capable of providing service from any of eight different orbital slots”.

Yet the bus for the mission has an interesting back story. Originally destined from mid-2006 to support EchoStar’s CMBStar satellite, with an anticipated major role in covering the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, its fabrication was suspended to review its performance specifications. It was eventually canceled. Following the contracts to develop EchoStar-23, the bus was rescoped to support the new mission. After launch, EchoStar-23 will undergo approximately three months of on-orbit testing at 86.4 degrees West longitude, before it is maneuvered into its planned operational “slot” at 44.9 degrees West.

The EchoStar-23 satellite is designed for up to 15 years of operational service at geostationary altitude. Photo Credit: EchoStar Corp.

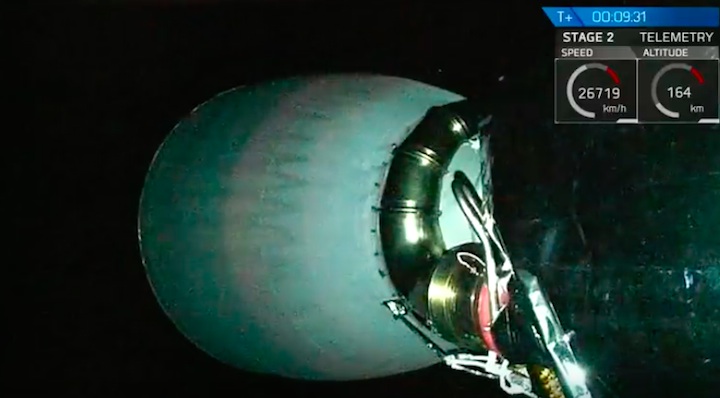

EchoStar-23 is one of SpaceX’s heaviest payloads to date, weighing around 12,000 pounds (5,500 kg). It carries a pair of X-shaped solar array “paddles” and can support an operational life span at geostationary altitude of 15 years. It is expected that the satellite’s End-of-Life (EOL) power will be in the region of 20 kilowatts. Equipped with Ku-, Ka- and S-band transponders for Direct-to-Home (DTH)/Direct Broadcast Satellite (DBS) services, EchoStar-23 will operate under a Brazilian government contract and, according to a report last November by Space News, is required to be ready for operational service by mid-2017.

Launch was targeted for the third quarter of 2016, but the explosion of an Upgraded Falcon 9 on the pad, last September, caused a multi-month hiatus in SpaceX operations. Pending the resolution of this anomaly, EchoStar-23 was intended to be the first launch from Pad 39A since the end of the Space Shuttle era. However, late in January 2017, SpaceX announced the need for “additional testing of ground systems” at the pad and opted to fly the Commercial Resupply Services (CRS)-10 Dragon cargo mission to the International Space Station (ISS), ahead of EchoStar-23. After a 24-hour delay, Dragon speared smoothly to orbit on 19 February. And if EchoStar-23 flies on time early Tuesday, just 23 days will have elapsed between a pair of launches, the shortest interval from Pad 39A since April 1985, when shuttles Discovery and Challenger rocketed into orbit within 17 days of each other.

Pad 39A has now seen a total of 95 of the most historic missions ever conducted in the annals of space exploration. From the maiden voyage of the Saturn V in November 1967 to humanity’s first piloted expedition to lunar orbit in December 1968 and the effort to implant the first American boots on the Moon in July 1969, the complex hosted no fewer than 12 Apollo-era missions, bookended by the launch of the Skylab space station in May 1973. It then underwent significant modification and between April 1981 and July 2011supported 82 Space Shuttle launches—including the first shuttle-Mir docking flight, the first ISS construction mission and the final voyage of Columbia—before NASA handed it over to SpaceX on a 20-year lease in April 2014 for Falcon 9 operations. Last month, the site saw its first launch under the SpaceX banner, when the CRS-10 Dragon cargo mission was lofted to the ISS.

Significantly, however, Tuesday’s mission—whose a 2.5-hour “window” extends from 1:34 a.m. through 4:04 a.m. EDT—is expected to mark the first launch from Pad 39A in almost seven years to occur in the hours of darkness. The pad saw the rousing post-midnight ride of Apollo 17 to the Moon in December 1972 and was followed by 34 nocturnal shuttle launches between August 1983 and April 2010. These included the voyage of the first African-American astronaut, four of the five Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing missions and the first shuttle flight to begin the mammoth ISS construction campaign.

In readiness for launch, the 230-foot-tall (70-meter) Upgraded Falcon 9 booster was transferred from the Horizontal Integration Facility (HIF) to Pad 39A and elevated to the vertical on Tuesday, 7 March, by means of the Transporter-Erector (TE). SpaceX teams then pressed ahead with customary pre-launch procedures, with a brief Static Fire Test of the nine Merlin 1D+ engines of the first stage scheduled for Tuesday evening. This was delayed by 24-48 hours and eventually took place without incident on Thursday, 9 March. New rules, implemented after last September’s Amos-6 failure, require a customer’s payload to be installed atop the booster after the completion of the Static Fire Test. “Static fire of Falcon 9 just completed,” SpaceX tweeted Thursday evening. “Targeting EchoStar-23 launch from @NASA’s Kennedy Space Center on Mar. 14, early morning EDT.” The booster was subsequently returned to the horizontal, allowing the EchoStar-23 payload fairing to be integrated, before being elevated back to vertical on the pad.

According to the 45th Space Wing at Patrick Air Force Base, the outlook for the small hours of Tuesday morning calls for a 70-percent likelihood of acceptable weather conditions. Increased cloud cover over Central Florida, coupled with a “vigorous system” along the Gulf Coast, is expected to bring widespread showers and isolated thunderstorms over the weekend. However, the frontal boundary associated with the system should pass KSC by Monday, causing clouds to gradually diminish as launch time approaches. Lingering clouds, which pose a potential threat to the Thick Cloud Rule, are the main risk factor for Tuesday. In the event that the opening launch attempt is scrubbed, SpaceX will stand down for 48 hours, before a second effort early Thursday, when conditions are expected to improve to 80-percent-favorable. “Winds will lighten during the day on Wednesday and should be within liftoff constraints by the backup launch window early Thursday morning,” the 45th noted. “The main concern will be Liftoff Winds.”

In keeping with procedures implemented since the Amos-6 failure, the Upgraded Falcon 9 has benefited from a somewhat longer fueling regime on its two previous missions. Loading of rocket-grade kerosene (known as “RP-1”) and “densified” cryogenic oxygen is expected to begin around an hour before T-0. This is quite different from previous practice with the booster, which saw fueling commence about 35 minutes before T-0. The longer fueling regime is expected to be a temporary measure, until a further enhanced Falcon 9 upgrade enters service, later in 2017.

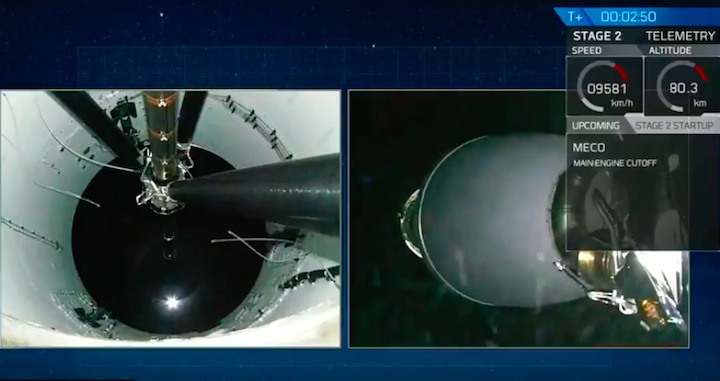

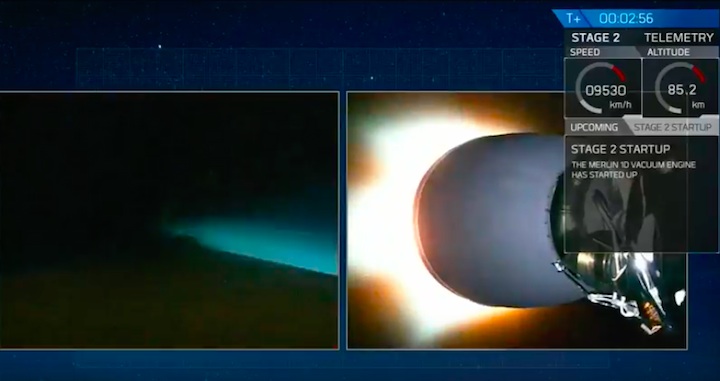

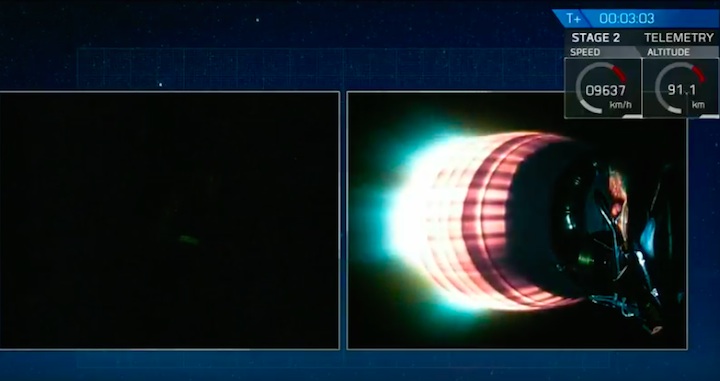

Passing T-10 minutes, the terminal countdown autosequencer will be initiated and the nine Merlin 1D+ engines of the first stage—which are configured in a circle of eight, with the ninth at the center—were chilled down, ahead of ignition. The vehicle will transition to internal power and assume primary command of all critical functions, going into “Startup” a minute before launch. At T-3 seconds, the nine Merlins will roar to life, pumping out a combined thrust of 1.5 million pounds (680,000 kg). Following liftoff, the first stage will power uphill for the opening minutes, before the second stage and its restartable Merlin 1D+ Vacuum engine picks up the baton to deliver EchoStar-23 to orbit.

Quelle: AS

-

Update: 16.03.2017

.

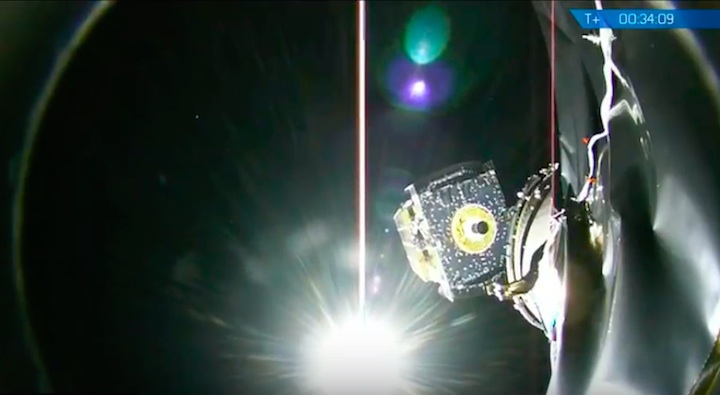

Erfolgreicher Start von Falcon-9 mit EchoStar 23 Satelliten

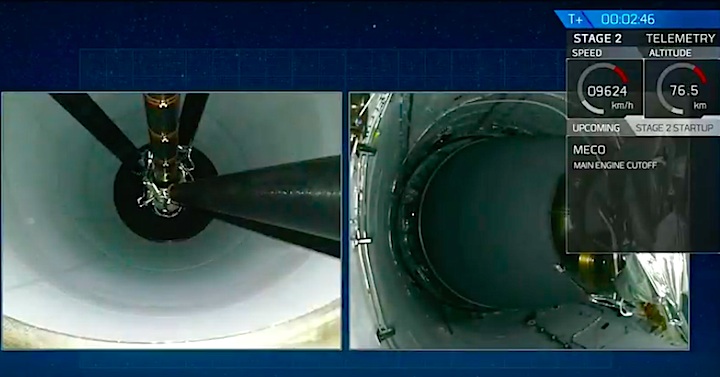

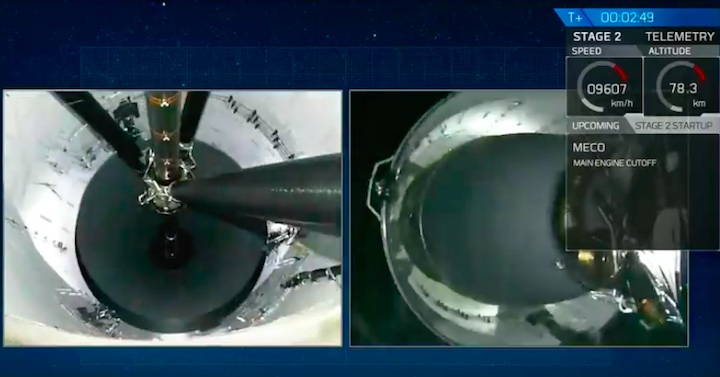

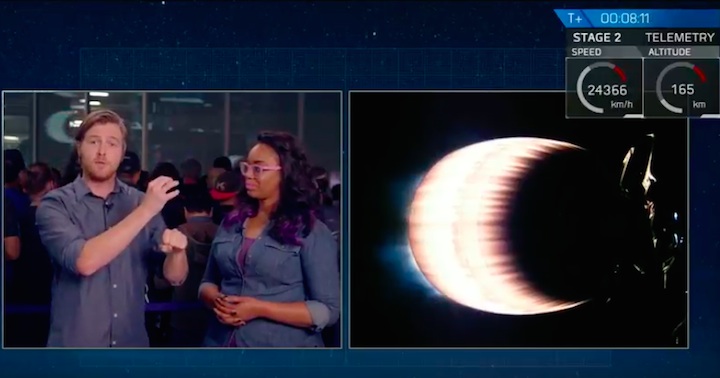

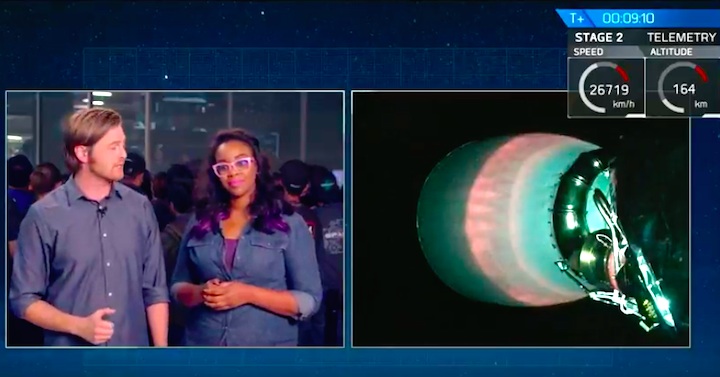

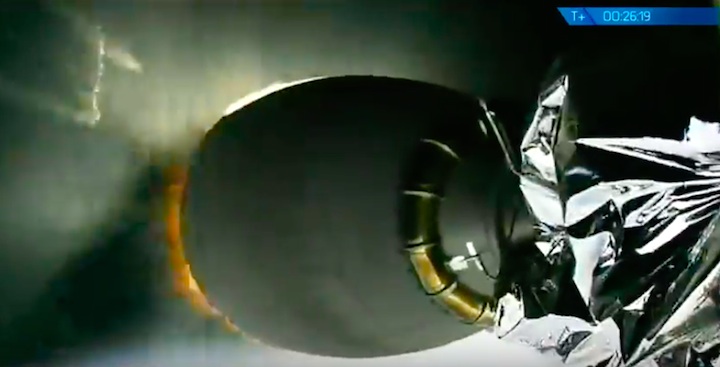

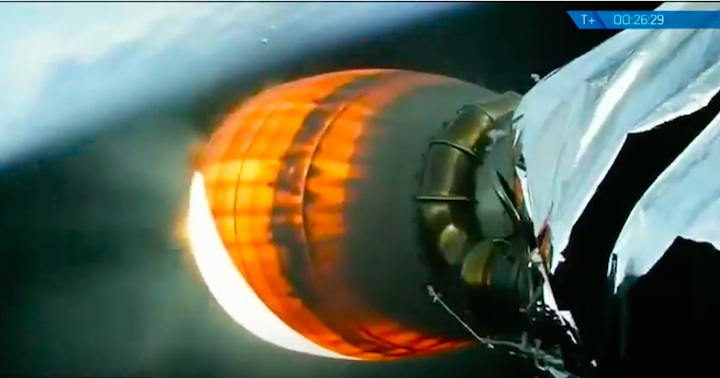

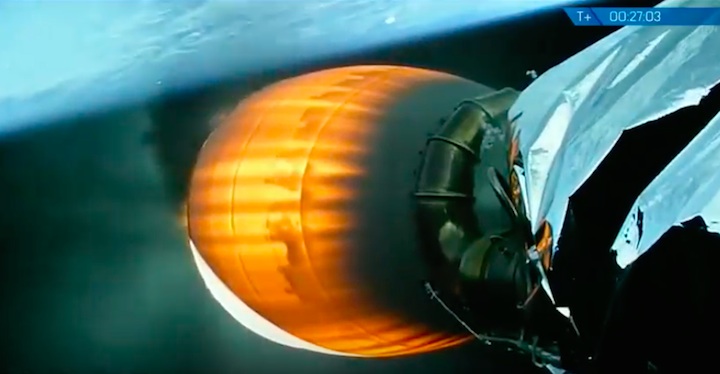

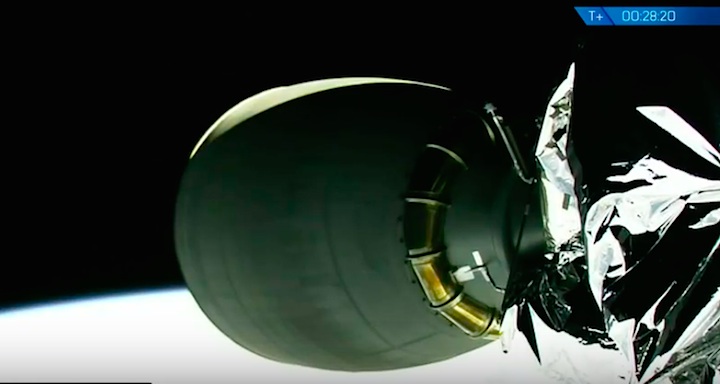

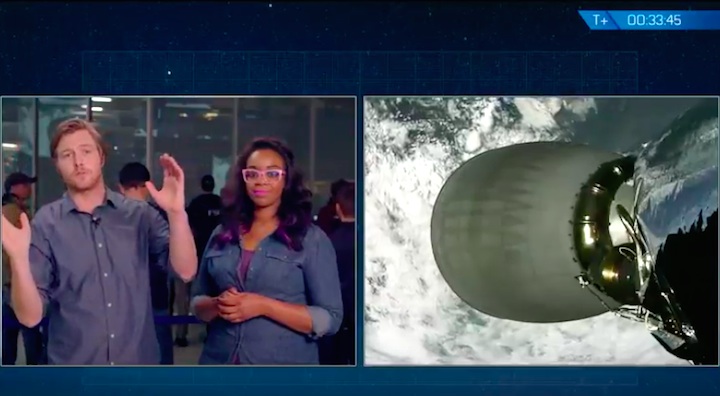

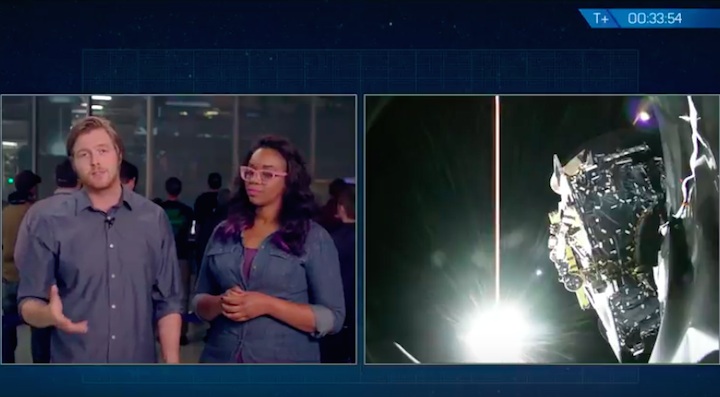

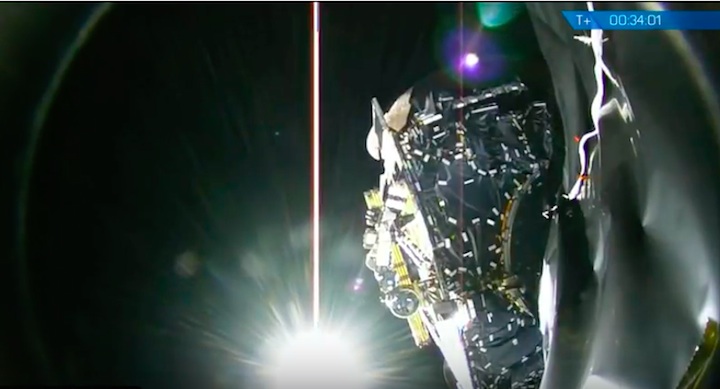

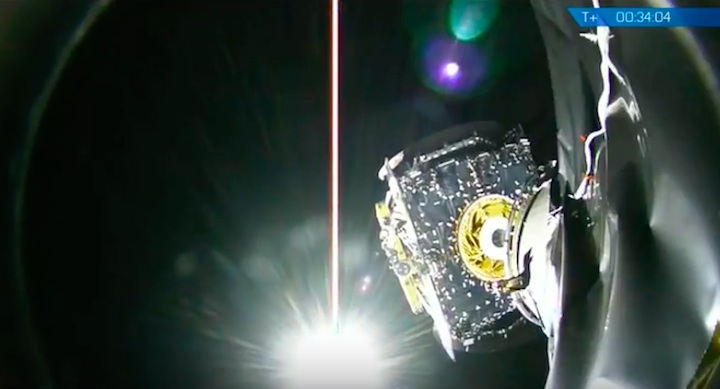

Frams von LIVE-Start:

Quelle: SpaceX