The NASA spacecraft that could one day help ferry humans to Mars is scheduled to undergo a parachute test tomorrow (March 8).

The Orion spacecraft can carry humans on long trips into deep space, but once it returns to Earth, it needs a little help touching down. Like the Apollo spacecraft, Orion relies on a parachute system to lower it down through Earth's atmosphere, and safely return astronauts to the ground.

The test is scheduled to take place at 7:30 a.m. local time (9:30 a.m. EST/1430 GMT) at the U.S. Army’s Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona. A model of Orion will be dropped from a C-17 aircraft flying at an altitude of 25,000 feet, according to a statement from the agency. NASA is currently investigating the possibility of flying two astronauts on a test flight of the Orion spacecraft as early as 2019.

Tomorrow's parachute test will simulate what would happen if an abort sequence took place during Orion’s launch. If something goes wrong with NASA's Space Launch Systems (SLS) rocket that Orion is riding on, NASA officials may decide to abort the flight, meaning the spacecraft would be ejected from its seat atop the rocket. In such an event, the parachutes would deploy and drop the spacecraft safely back to Earth. During an abort sequence, the spacecraft will be traveling at the relatively slow speed of about 130 mph [210 km/h], rather than speeds of about 310 mph [500 km/h] during re-entry after reaching space, according to NASA. The drop will last for about four minutes total; the last one to two minutes will take place under fully deployed parachutes, according to a NASA representative.

This will be Orion's second airdrop parachute test in a series of eight qualifying drop tests that will replicate various scenarios in which Orion's parachute system would need to be deployed, according to the statement.

Quelle: SC

---

Update: 10.03.2017

.

Orion’s parachutes tested under launch abort conditions

A model of NASA’s Orion spacecraft, in development to loft astronaut crews into deep space, was dropped from a U.S. Air Force cargo plane over Arizona on Wednesday in the latest in a series of tests to verify the capsule’s parachutes are up to the job of safely landing with humans on-board.

The instrumented test module, shaped like the real Orion capsule with a foam shell, was deployed from the cargo bay of the C-17 transport plane at an altitude of 25,000 feet — about 7,600 meters — Wednesday morning over the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona.

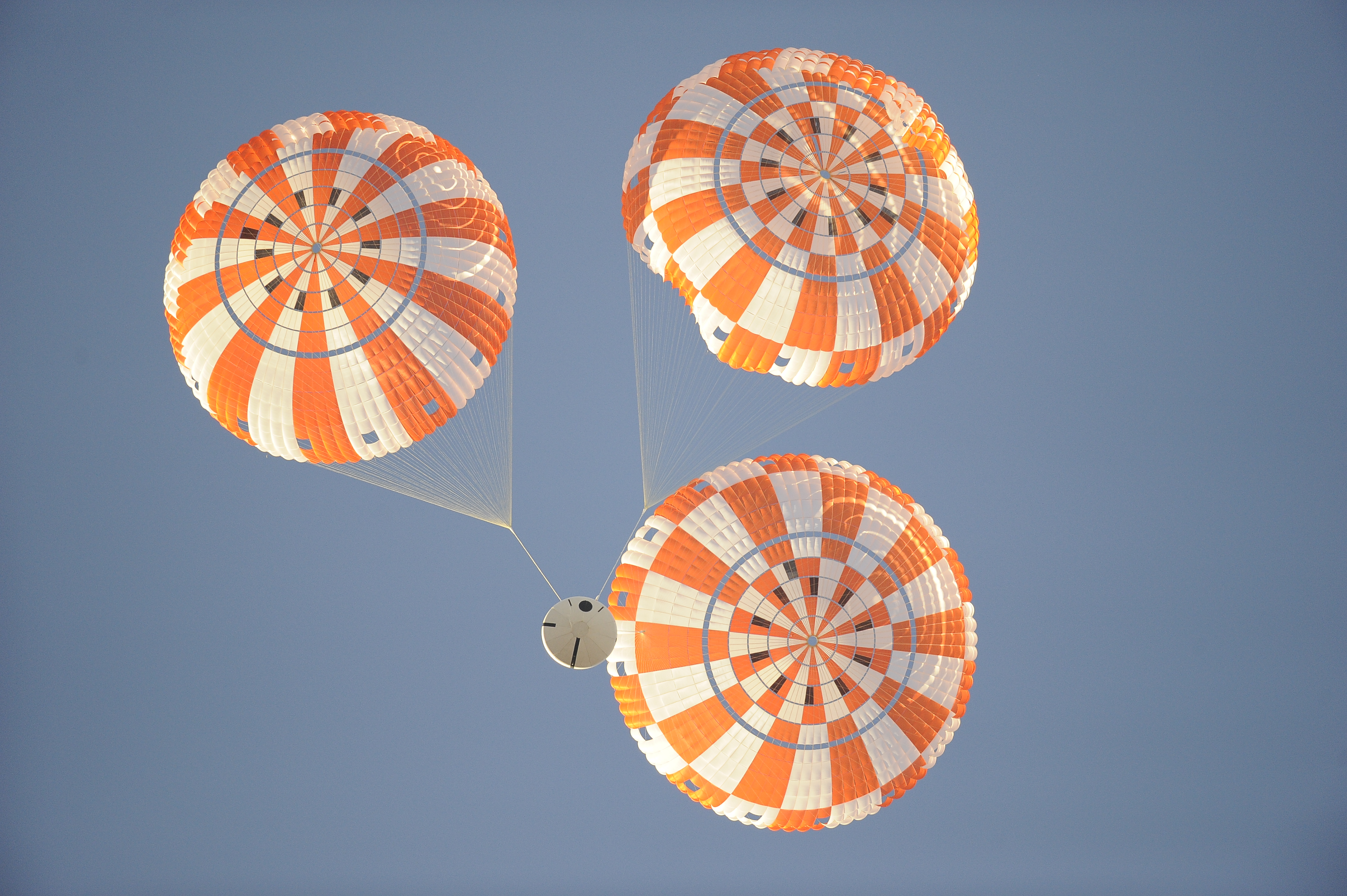

Two drogue parachutes unfurled to steady the descending capsule, then three 116-foot-diameter (35-meter) orange and white main parachutes inflated to slow down for landing. The descent profile mimicked the conditions an Orion spacecraft would see in the event of an abort during launch, beginning at a relatively slow speed of 130 mph (209 kilometers per hour) instead of the 310 mph (499 kilometers per hour) at which the parachutes would deploy at the end of a normal mission.

Engineers were expected to analyze the performance of the two drogue parachutes at low speeds, and the inflation of the three main parachutes, which were suspended 265 feet (80 meters) above the capsule before touchdown in the desert in southwest Arizona.

The test was the second of eight drops designed to qualify the parachute system for human spaceflight. Instead of landing in the desert, Orion capsules returning from space or a launch abort will splash down at sea.

The Orion spacecraft has performed one space mission to date — an unpiloted test flight in Earth orbit in December 2014 — and the next mission is scheduled for no earlier than late 2018 on a trip into lunar orbit and back, also without astronauts.

Following a request from the Trump administration, NASA is studying whether to add a two-person crew to the next Orion mission, which will lift off on the first flight of the agency’s Space Launch System rocket, for a round-trip voyage around the moon. A decision to fly astronauts on the next Orion flight, named Exploration Mission-1, would delay the launch past next year to complete development and testing of the capsule’s abort and life support systems, and add to the program’s cost, officials said last month.

The on this page show the capsule’s drop from the C-17, its descent under parachutes, and the recovery team swarming around the engineering test craft after landing.

NASA and its Orion contractor, Lockheed Martin, plan to reuse the test parachutes flown Wednesday. The capsule will also be refurbished, have new foam added, and reused on four of the remaining six drop tests. A dart-shaped mass simulator will be dropped on the other two qualification tests in the coming months.

The foam damage seen in the images is expected. The outer foam shell is “sacrificial” and designed to protect the capsule’s primary structure and avionics, according to Jared Daum, a hardware and parachute engineer working on Orion’s Capsule Parachute Assembly System.

None of the 11 parachutes used on a real Orion mission will be reused, Daum said.

Engineers will review video and data recorded during Wednesday’s drop test as they prepare for the next in the qualification series. Technicians will also inspect the parachutes and capsule for tears and dings.

“We’re one step closer,” Daum told reporters at the landing site. “We’ve got six more in our qualification series — still a lot of work to do.”

More images of the drop test are posted below, including views of astronauts Stan Love and Victor Glover observing the test, assisting in the recovery and discussing the event with news media.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 12.03.2017

.

A flight-sized boilerplate of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner touched down gently under parachutes against the backdrop of the San Andres Mountains in late February, providing a preview of how the spacecraft will return to Earth in upcoming NASA missions. Boeing is developing the Starliner to take astronauts to and from the International Space Station in partnership with NASA’s Commercial Crew Program.

The parachute test is one in a series that will allow the vehicle to pick up the same velocity as the actual spacecraft when returning to Earth in the southwest region of the United States from the International Space Station. The goal of the test series is to prove the design of the Starliner’s parachutes.

“Completion of this test campaign will bring Boeing and NASA one step closer to launching astronauts on an American vehicle and bringing them home safely,” said Mark Biesack, spacecraft systems lead for the agency’s Commercial Crew Program.

The test began at the Spaceport America facility near the Army’s White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. During the test, the Starliner was lifted about 40,000 feet in the air, the flying altitude of a typical commercial airline flight, by a Near Space Corp. helium balloon and then released over the White Sands Missile Range.

Given the flight-like characteristics and the large size of the capsule, Boeing was not able to fit the Starliner test article into the hold of a C-130 or C-17 aircraft. Their solution, a 1.3-million-cubic-foot balloon, which is able to lift the capsule to its intended altitude.

“This parachute test, as well as the subsequent tests in Boeing’s qualification test campaign, provides valuable data, because the test article has the same mass, outer mold line, and center of gravity as the flight vehicle,” said Biesack. “The high-fidelity data they receive from these tests will anchor predicted models of realistic parachute deployment.”

Attached underneath the Starliner boilerplate was a large, yellow stabilization weight used to orient the test vehicle’s angle of attack and speed of descent. As the Starliner descended to the desert at speeds of 300 miles per hour, a series of dynamic events slowed the spacecraft. Shortly after the Starliner was released from the balloon, the spacecraft deployed two drogue parachutes at 28,000 feet to stabilize the spacecraft, then its pilot parachutes at 12,000 feet. The main parachutes followed at 8,000 feet above the ground prior to the jettison of the spacecraft’s base heat shield at 4,500 feet. Finally, the spacecraft touched the ground lightly, kicking up the desert sand.

During missions to the station, the Starliner will be equipped with large air bags that will cushion the impact during landing. The Boeing design calls for the spacecraft to be reused up to ten times, and a land-landing will aid with reusability. In the event of an emergency, the spacecraft also can splash down in the ocean.

The Starliner spacecraft will launch on an Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. NASA also is partnering with SpaceX to develop a crew transportation system all in an effort to return to U.S. human spaceflight launches from American soil. SpaceX will launch its Crew Dragon spacecraft on the company’s Falcon 9 rocket from Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

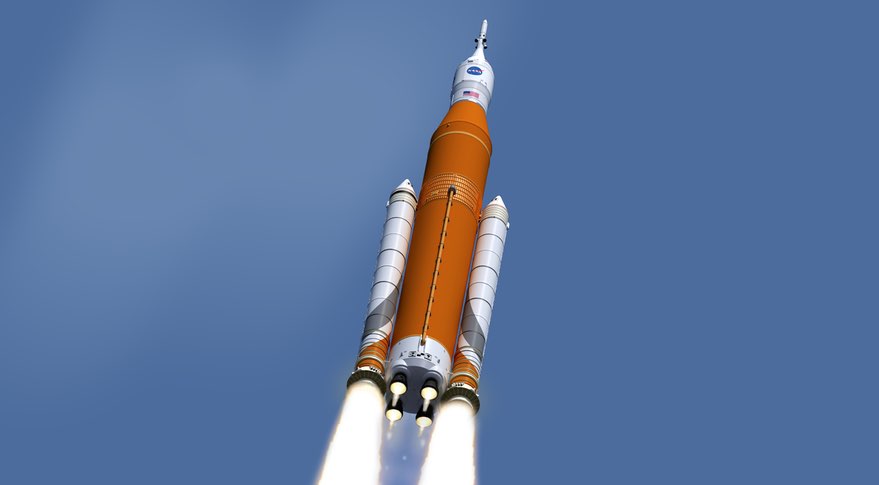

Upper stage arrives for NASA's big SLS rocket

The upper stage for NASA’s next big exploration rocket has arrived at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

United Launch Alliance’s Mariner ship delivered the “interim cryogenic propulsion stage,” or ICPS, from its factory in Decatur, Alabama, reaching Port Canaveral last Tuesday.

The hydrogen-fueled stage is a modified version of the one flown on ULA’s Delta IV rocket.

If plans hold, the stage will fly only once, on the inaugural test fight of NASA’s Space Launch System rocket.

After that, NASA plans an upgrade to the more powerful Exploration Upper Stage, or EUS.

NASA tentatively is targeting a first launch of the SLS late in 2018 on Exploration Mission-1, or EM-1, flying an Orion capsule around the moon.

The second mission, EM-2, would fly no sooner than 2021 and as late as 2023, in part because of time needed to modify ground systems to handle the larger upper stage.

NASA is studying whether to fly astronauts on the first SLS flight, a change that would delay the mission at least into 2019.

Quelle: Florida Today