“GMRT is a world-class instrument, recently upgraded with new receivers, and was able to detect the very faint signal” coming from the ultimately doomed Schiaparelli EDM lander on Mars.

The GMRT (Giant Metre-wave Radio Telescope), NCRA. Credit: National Centre for Radio Astrophysics/Tata Institute of Fundamental Research

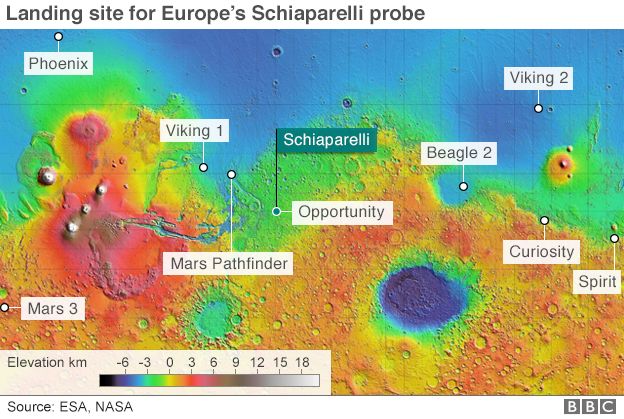

In December 2003, a British mission to Mars called Mars Express was nearing the red planet for the final part of its journey. It consisted of two parts: the Mars Express Orbiter, which would get into orbit and study the planet’s surface and subsurface composition and atmosphere; and the Beagle 2 lander, a set of instruments that would drop to the surface, remain stationary and make measurements of their own. The deployment was supposed to happen on December 19 – and it did. By December 25, the Mars Express Orbiter was in an elliptical orbit around the planet and began its observations. However, even by February 2004, mission scientists didn’t know what had happened to Beagle 2.

In fact, they wouldn’t know until 12 years later, when NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spotted the lander sitting intact on Mars’s surface. Scientists hadn’t been able to contact Beagle 2 because two of its solar panels hadn’t fully unfurled, blocking the antenna.

Since the 1960s, scientists have had bad luck with Mars landers, especially in the late 1990s. However, in all this time, they haven’t equipped landers with radio antennae that transmit data as the craft descends to the surface, instead choosing to rely on the communications antenna that comes online only after the lander has landed healthily. Before the Beagle 2 failure in 2003, there was NASA’s Mars Polar Lander failure in 1999, whose fate hasn’t been confirmed still. And after Beagle 2, there was the Schiaparelli lander of the Euro-Russian ExoMars mission on October 19 this year. Though the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter got into Mars orbit comfortably, the lander appears to have crashed on the martian surface.

This time, however, there was confirmation – as well as live transmission as the lander descended, thanks to the world’s largest telescope of its kind located in Maharashtra, India.

A world-class telescope

The National Centre for Radio Astrophysics (NCRA) to the city’s north is home to the aptly named Giant Metre-wave Radio Telescope (GMRT). Built at $20 million and going operational in 1995, the GMRT is actually an array of 30 telescopes each observing radiation coming in from space with a wavelength in the order of metres – or radio-frequency. The telescopes rely on a technique called aperture synthesis to make their studies. The larger a telescope’s antenna is, the higher the resolution with which it can observe its targets. Aperture synthesis allows multiple telescopes to act as a single giant antenna, where the size of the antenna is the distance between the most separated telescopes in the network. In the case of GMRT, this is 25 km.

There is no telescope bigger than the GMRT when it comes to observing in the metre wavelength, which corresponds to radio waves. It is often used to study distant galaxies, blackholes, quasars and other high-energy cosmic objects billions of lightyears away. And because of its sensitivity, the GMRT can also be used to detect faint radio signals coming from objects closer to Earth – for example, a lander descending on Mars.

“It wasn’t that the technology didn’t exist,” Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Centre for Astrophysics at Harvard University, told The Wire. “In the earlier landing failures, there was no live radio link with Earth. I think this was mostly to save money. They didn’t put a transmitter on the probes that was strong enough to reach Earth.” However, after the failures in 1999 and 2003, it became imperative to be able to understand how landers failed so frequently. “After those losses, people realised it was a very bad idea not to have a radio link, you just don’t know what went wrong if it failed.”

In the case of the Schiaparelli lander of the ExoMars mission, scientists found that a software glitch could have forced the lander’s parachute to separate sooner than necessary, causing the lander to crash at 300 km/hr. This information wouldn’t have been available now if not for the GMRT.

In fact, scientists have also noted a difference between data received at the GMRT and that collected by probes orbiting Mars when Schiaparelli stopped working, and are currently following this up.

The GMRT experiment

The Schiaparelli lander had been equipped with an ultra-high frequency (UHF) radio onboard to allow it to communicate with orbiters currently around Mars; the orbiters would’ve then relayed the signal to receiving stations on Earth. But with the ExoMars mission, scientists wanted to experiment with the GMRT – even though Schiaparelli’s UHF radio wasn’t powerful enough to transmit all the way to Earth, a distance of 54 million km, the telescope seemed sensitive enough to be able to pick that up.

According to Thomas Ormston, a spacecraft operations engineer at the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, “In practice testing during Schiaparelli separation from the [ExoMars orbiter], we did see the weak trace of the signal from the lander at GMRT” with only 18 telescopes in the array available at the time. Ormston also wrote that there had been some concerns during the descent phase that GMRT might not receive the signal if Schiaparelli’s radio was facing away.

McDowell clarified that “the amount of radio interference in [the radio] waveband is lower in Maharashtra than in some other parts of the world where there are radio telescopes”. According to the NCRA, which operates the GMRT, “Manmade radio interference is considerably lower in this part of the spectrum in India.”

Separation of EDM from TGO as detected at GMRT, Pune, on 16 October 2016. Caption: Thomas Ormston/ESA. Credit: GMRT/NASA/JPL

Good for Russia and India

Moreover, the ExoMars mission is being conducted in two phases. The first just finished while the second begins in 2020, when the European Space Agency (ESA) and its Russian counterpart Roscosmos will jointly deploy a rover on the martian surface. Knowing now as to what killed the lander, as opposed to 12 years down the line, will be of great help in lowering the rover properly. “GMRT is a world-class instrument, recently upgraded with new receivers, and was able to detect the very faint signal,” McDowell explained. “That signal will help engineers study the ExoMars EDM lander’s descent, both seeing how well the bits that work did work and seeing what went wrong with the bits that didn’t.”

According to people familiar with the upgrades, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, helped equip GMRT with the special receivers.

That the GMRT experiment was a success is also good news for Russia as well as India. Between 1960 and 1988, the USSR participated in 17 missions to Mars; and between 1996 and 2016, in three (including Schiaparelli). And in these 20 missions, the Russians have found success only in two missions – the last time in 1973. Even then, the Mars 5 mission lasted just nine days against its planned lifetime of at least one year. In fact, the USSR/Russia’s last successful interplanetary expedition was the Vega program to Venus, followed by a flyby of Halley’s comet, that concluded in 1985.

Though ESA has declared the Schiaparelli part of the mission a success (because it did demonstrate that its way of landing almost worked), its landing gear was built by Russian engineers, the same people who will be responsible for landing the rover in 2021. With GMRT data – as McDowell said – they will know now what bits worked and what didn’t.

As for India: the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) plans to launch a rover as well as a lander on Mars between 2020 and 2022, in a mission it has called Mangalyaan 2. As with the previous mission, which succeeded in September 2014 when the Mars Orbiter got into orbit around Mars, the rover and lander may also be successful on ISRO’s first try. And the GMRT could play an important role in ensuring that.

Quelle: WIRE

---

Computing glitch may have doomed Mars lander

Researchers sift through clues after Schiaparelli crash in hopes of averting mistakes in 2020 mission.

A model of the ExoMars lander Schiaparelli, in front of European Space Agency scientists explaining its failed landing on Mars.

Photos of a huge circle of churned-up Martian soil leave few doubts: a European Space Agency (ESA) probe that was supposed to test landing technology on Mars crashed into the red planet instead, and may have exploded on impact.

The events of 19 October may be painful for ESA scientists to recall, but they will now have to relive them over and over again in computer simulations. The lander, called Schiaparelli, was part of ESA's ExoMars mission, which is being conducted jointly with the Russian Space Agency Roscosmos. It was a prelude to a planned 2020 mission, when researchers aim to land a much larger scientific station and rover on Mars, which will drill up to 2-metres down to look for signs of ancient life in the planet’s soil. Figuring out Schiaparelli’s faults and rectifying them is a priority, says Jorge Vago, project scientist for ExoMars. “That’s super important. I think it’s on everybody’s mind.”

Anatomy of a crash

Unlike the British-led and ESA-operated Beagle 2 mission, which disappeared during its landing on Mars on Christmas Day 2003, Schiaparelli sent data to its mother ship during its descent. Preliminary analysis suggests that the lander began the manoeuvre flawlessly, braking against the planet’s atmosphere and deploying its parachute. But at 4 minutes and 41 seconds into an almost 6-minute fall, something went wrong. The lander’s heat shield and parachute ejected ahead of time, says Vago. Then thrusters, designed to decelerate the craft for 30 seconds until it was metres off the ground, engaged for only around 3 seconds before they were commanded to switch off, because the lander's computer thought it was on the ground.

The lander even switched on its suite of instruments, ready to record Mars’s weather and electrical field, although they did not collect data. “My guess is that at that point we were still too high. And the most likely scenario is that, from then, we just dropped to the surface,” says Vago.

The craft probably fell from a height of between 2 and 4 kilometres before slamming into the ground at more than 300 kilometres per hour, according to estimates based on images of the probe’s likely crash site, taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on 20 October.

The most likely culprit is a flaw in the craft’s software or a problem in merging the data coming from different sensors, which may have led the craft to believe it was lower in altitude than it really was, says Andrea Accomazzo, ESA’s head of solar and planetary missions. Accomazzo says that this is a hunch; he is reluctant to diagnose the fault before a full post-mortem has been carried out. But if he is right, that is both bad and good news.

European-designed computing, software and sensors are among the elements of the lander that are to be reused on the ExoMars 2020 landing system, which, unlike Schiaparelli, will involve a mixture of European and Russian technology. But software glitches should be easier to fix than a fundamental problem with the landing hardware, which ESA scientists say seems to have passed its test with flying colours. “If we have a serious technological issue, then it’s different, then we have to re-evaluate carefully. But I don’t expect it to be the case,” says Accomazzo.

The ExoMars team will try to replicate the mistake using a virtual landing system designed to simulate the lander’s hardware and software, says Vago, to make sure that scientists understand and can deal with the issue before redesigning any aspects of ExoMars 2020.

2020 vision

The rover mission has already been delayed by two years, owing to hold-ups on both Russian and European sides, but Vago believes that making tweaks to its design will not push the mission back. “At this point, no one wants to think about flipping to 2022. It was painful enough to go from 2018 to 2020,” he says.

The 2020 mission still has a budget shortfall of around €300 million (US$326 million), which ESA will request from European Union member states at a meeting of ministers in December. Asked at a press briefing on 20 October whether Schiaparelli’s failure would jeopardize the mission, ESA director general Johann-Dietrich Wörner said it wouldn’t have any impact. “We have the function which we need for the 2020 mission, so we don’t have to convince them, we just have to show them,” he told reporters.

But Vago is more pragmatic. “It would have been much nicer to be able to go to the ministers with a mission where both elements had performed flawlessly.”

ESA is keen to stress that overall, the ExoMars mission can be seen as a triumph: Schiaparelli sent back test data from the majority of its descent, and its sister craft — the Trace Gas Orbiter — successfully manoeuvred into Martian orbit. The orbiter is the more scientifically valuable of the two halves of the mission: from December 2017, it will study Mars’s atmosphere, aiming to find evidence for possible biological or geological sources of methane gas. It will also be a communications relay for the 2020 rover.

“As it is, we have one part that works very well and one part that didn’t work as we expected,” says Vago. “The silver lining is that we think we have in hand the necessary information to fix the problem.”

Quelle: nature

---

Mars lander crash complicates follow-up rover in 2020

Engineers at the European Space Agency (ESA) are racing to figure out what went wrong with the Schiaparelli Mars lander. On 19 October, it seemed to drop out of the sky and crash to the surface less than a minute before its planned soft landing. A diagnosis is urgent, because many of the same pieces of technology will be used to get a much bigger ExoMars rover down to the surface in 2020.

More than engineering is at stake. If the ExoMars 2020 rover is to fly at all, ESA must persuade its 22 member states to chip in to cover a €300 million shortfall in the €1.5 billion cost of both the 2016 and 2020 phases of ExoMars. On 1–2 December, at a meeting of government ministers, ESA officials will make their case that they are not throwing good money after bad. After the Schiaparelli loss, securing funding for ExoMars 2020 “is really more important than ever, if Europe wants to be seen as part of exploring our solar system,” says David Southwood of Imperial College London, who was ESA’s director of science from 2001 until 2011.

At the ministerial meeting, ESA officials will emphasize the success of the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), the other part of the ExoMars 2016 mission. As Schiaparelli fell to its doom, the TGO entered a highly elongated 4.2-day orbit around Mars. Next month, it will begin to calibrate science instruments designed to sniff out methane and other trace gases in the atmosphere to pinpoint their origin—not just where they arise, but whether they emanate from geological or biological sources. In March 2017, TGO will begin dipping down into the martian atmosphere, generating friction that will slow and circularize its orbit so that it can begin science observations later in the year. “We have 100 kilograms of science instruments in orbit around Mars. Solving the mystery of methane is now in our future,” David Parker, ESA’s director of human spaceflight and robotic exploration, told reporters last week.

Compared with the expected science return of the TGO, the weather data that Schiaparelli would have collected with just a few days of battery power on the surface was an afterthought. But as students of ESA’s comet-orbiting Rosetta mission learned, the fate of plucky landers resounds in the public consciousness. In November 2014, Rosetta dropped the Philae lander to the surface of a comet, where it survived a couple days. Even though its few pictures and measurements were far surpassed by those of its mother ship, it captured the public’s fancy and was a public relations coup.

ESA engineers studying what happened to Schiaparelli are working with information from several sources: data the lander transmitted to the TGO during its descent and elements of the same signal that were picked up by ESA’s Mars Express orbiter and a radio telescope on Earth. All sources agree that the signal abruptly stopped around 50 seconds before the expected landing. Early analysis suggested that something went awry after the lander shed its parachute and heat shield and fired its thrusters to slow the final descent. That transition seemed to begin too soon, and the thrusters only fired for a few seconds before cutting out.

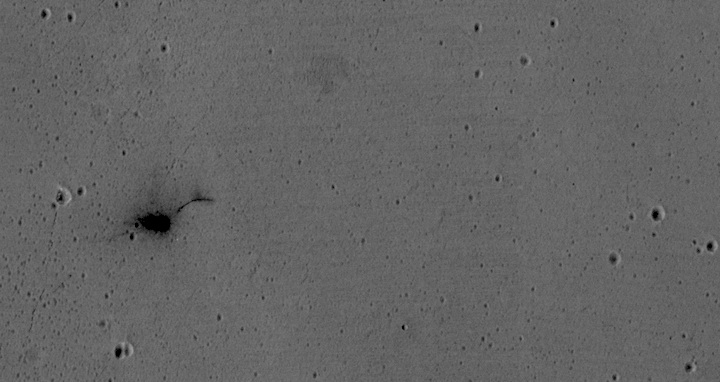

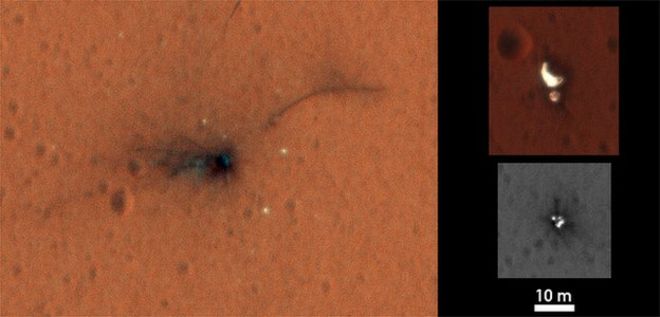

On 20 October, the day after the landing, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) flew over the landing site and snapped images with its low-resolution camera. These showed a white dot, thought to be Schiaparelli’s parachute, and 1 kilometer away a fuzzy dark patch, 15 by 40 meters in size. ESA says this dark smudge is probably soil disturbed by the impact of Schiaparelli or even the scar of an explosion, since the lander’s propellant tanks would have been full on impact. ESA says the lander probably fell from a height of up to 4 kilometers (the parachute was meant to release it at 1.1 kilometers), and that it would have hit the ground at 300 kilometers per hour. MRO is expected to take more pictures of the site this week with its high-resolution camera.

The pressure is on Schiaparelli’s engineers because the ExoMars 2020 rover and its landing platform are already taking shape. Many components, which are being duplicated from Schiaparelli with little change, need to be shipped to Russia for integration into the spacecraft by next year, says Thierry Blancquaert, Schiaparelli’s mission manager. The aeroshell that will protect the 2020 rover during descent and slow it as it enters the atmosphere is the same shape but instead will be built by Russia, which has been partnering with ESA on the ExoMars program since NASA pulled out in 2012. The parachute in 2020 will be the same type but will deploy in two phases—a small one followed by a big one—and the main chute will be much larger: 35 meters across compared to Schiaparelli’s 12 meters.

The thrusters that will ease the 2020 rover onto the surface will be different, and are currently being developed by Russian space agency Roscosmos. But the radar Doppler altimeter—which senses the surface and allows the thrusters to bring the spacecraft down gently—as well as the guidance and navigation systems will be the same as Schiaparelli’s, so those parts of last week’s descent will be under special scrutiny.

Earlier this year, the planned launch date for the rover was delayed from 2018 to 2020 because of problems mating the ESA-built rover with the Russian aeroshell. Many see this as a blessing in disguise. “The industrial and instrument teams were following aggressive schedules, but the delay is a bit of relief,” says Andrew Coates of University College London, principal investigator of the rover’s PanCam imaging system. “Now there’s time to do something about it.”

It remains to be seen whether government ministers will decide that the 2020 mission is a good bet. Enthusiasts like Southwood say ESA needs to follow the example of NASA which, despite a series of Mars mission failures in the 1990s, kept doggedly at it. “Space exploration is tough. As long as we believe in its societal worth, Europe needs to show the same resolve as our American cousins.”

Even with seven successful landings under its belt, Mars still makes NASA engineers anxious, says Allen Chen, who heads the entry, descent, and landing team for NASA’s Mars 2020 mission at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Mars’s thin and unpredictable atmosphere means much can go wrong. Like ESA, NASA is also planning to drop a rover to the surface in 2020, as is China. “Every Mars landing attempt teaches us things,” Chen says. “The only true failure is to stop trying.”

Quelle: AAAS

-

Update:

-

The most powerful telescope orbiting Mars is providing new details of the scene near the Martian equator where Europe's Schiaparelli test lander hit the surface last week.

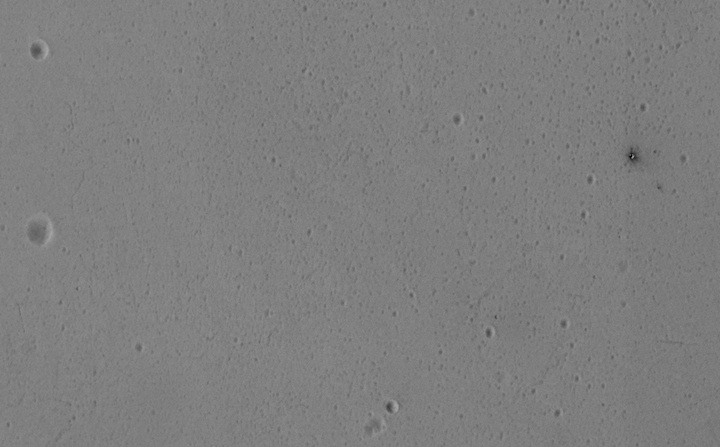

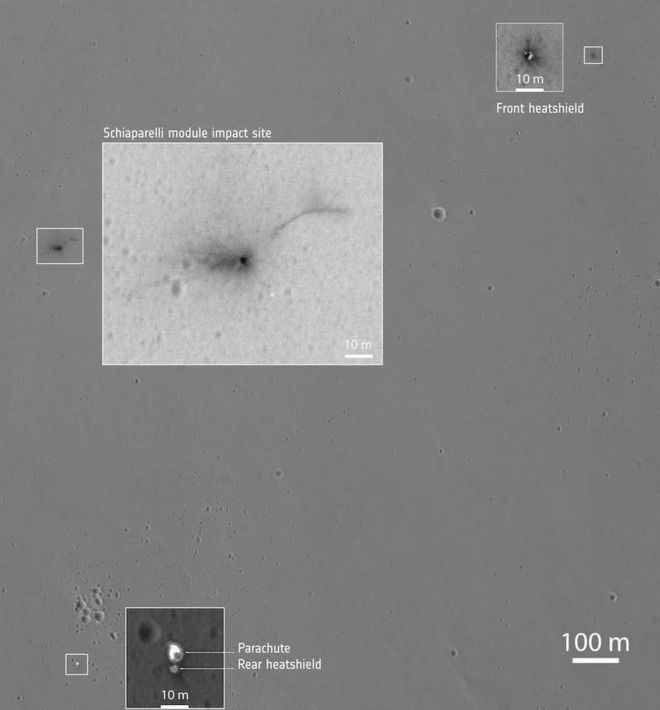

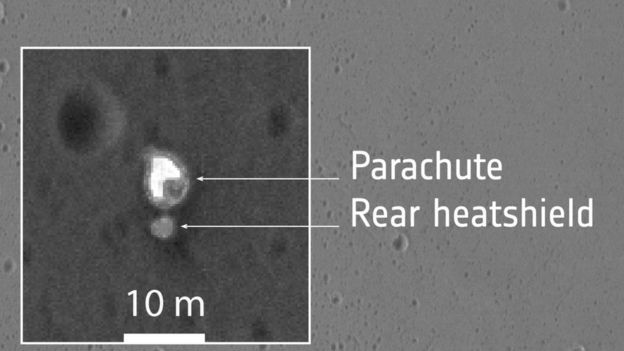

An Oct. 25 observation using the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows three impact locations within about 0.9 mile (1.5 kilometers) of each other.

The scene shown by HiRISE includes three locations where hardware reached the ground. A dark, roughly circular feature is interpreted as where the lander itself struck. A pattern of rays extending from the circle suggests that a shallow crater was excavated by the impact, as expected given the premature engine shutdown. About 0.8 mile (1.4 kilometers) eastward, an object with several bright spots surrounded by darkened ground is likely the heat shield. About 0.8 mile (1.4 kilometers) south of the lander impact site, two features side-by-side are interpreted as the spacecraft's parachute and the back shell to which the parachute was attached. Additional images to be taken from different angles are planned and will aid interpretation of these early results.

The test lander is part of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 mission, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on Oct. 19. The orbiter will investigate the atmosphere and surface of Mars and provide relay communications capability for landers and rovers on Mars.

Data transmitted by Schiaparelli during its descent through Mars' atmosphere is enabling analysis of why the lander's thrusters switched off prematurely. The new HiRISE imaging provides additional information, with more detail than visible in an earlier view with the Context Camera (CTX) on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

With HiRISE, CTX and four other instruments, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has been investigating Mars since 2006.

Quelle: NASA

-

Update: 28.10.2016

.

Images reveal crashed Mars lander

Image copyrightNASA

Image copyrightNASAThe European Space Agency has tried hard to avoid using the words "crash" or "failure" about its attempted Mars landing but the fate of the spacecraft is cruelly exposed in new pictures.

The Schiaparelli lander is seen in greater detail than ever before, lying on the Martian surface.

It is well within its intended landing zone but obviously unable to function.

The images, gathered by Nasa, could provide important new clues about what went wrong.

They show a dark patch around the capsule - a possible hint that a fuel tank exploded - and the indication is that the impact gouged out a crater 50cm deep.

Last week's landing - a joint Esa-Russian Space Agency (Roscosmos) endeavour - was billed as a "technology demonstrator" to pave the way for a far bigger venture in 2020 with a sophisticated rover to hunt for clues about life.

The loss raises difficult questions about the risks involved in that follow-on mission and whether Esa's member governments will be too nervous to pledge the funds needed to mount it.

The Schiaparelli spacecraft was meant to touch down last week using a combination of a heat-shield and a parachute to slow its fall and retro-rockets to lower it to the surface.

Image copyrightNASA

Image copyrightNASA

Instead communications were lost during what should have been the final minute of the descent and it is estimated that the spacecraft hit the ground at about 300kph.

It was quickly established that the parachute and back cover were released earlier than they should have been, according to a pre-programmed sequence of tasks.

It is also known that the retro-rockets, which should have fired for 30 seconds, only operated for three or four seconds, and the lander probably fell from a height of 2-4km.

In the aftermath of the attempt, Esa's Director-General, Jan Woerner, claimed that the mission was a success because the spacecraft transmitted data for five of the six minutes of its descent, providing useful information and proving that key stages of the operation had worked well.

He also highlighted that the lander's mother ship, known as the Trace Gas Orbiter, had been successfully placed in an orbit that would allow it to sniff the Martian atmosphere for hints of methane.

Soon after the mission, Nasa's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter gathered pictures of the landing zone which revealed the presence of two new dots in the Martian landscape - a dark one for the spacecraft and a white one for the parachute.

Now the same spacecraft has used its more powerful HiRise camera - with a resolution of 30cm per pixel - to focus on the landing zone and produce the images released today.

In a bitter irony, it was the same US orbiter that managed to spot Europe's earlier attempt at a Mars landing, with the Beagle-2 mission in 2003.

Those images showed how the tiny craft had made it to the surface in one piece but then failed to fully open its solar panels which meant that it could not communicate or survive.