This data could reveal a lot. Wikipedia

The noises coming from Jupiter sound like they’re straight out of a Halloween movie.

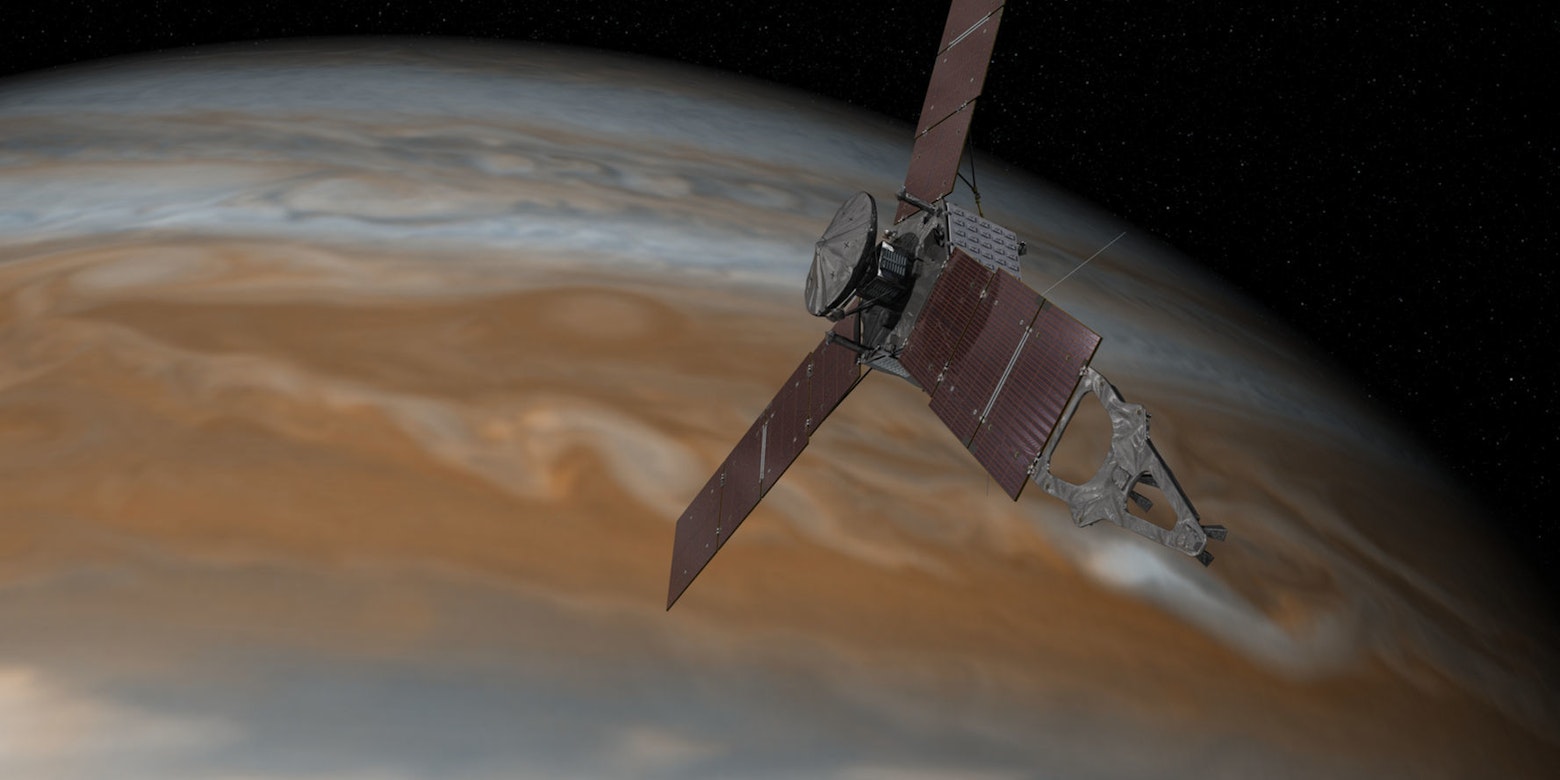

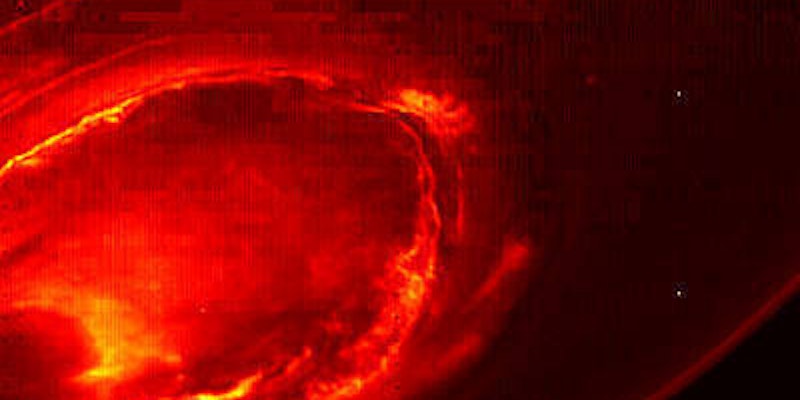

When NASA’s Juno spacecraft made its first full orbit around Jupiter on August 27, an instrument on board called Waves recorded the gas giant’s auroras. The emissions of the light show—which is similar to the northern and southern lights on Earth but on a vastly larger scale—were discovered in the 1950s but never able to be analyzed up close until now.

NASA engineers have recently shifted 13 hours of radio emissions from Jupiter’s intense auroras into the audio frequency range so they can be heard by the human ear. They fall between seven and 140 kilohertz.

In this video posted by NASA, they auroras are displayed both audibly and visually in a format similar to a voiceprint, meaning the intensity of the sound waves is depicted as a function of frequency in time. The warmer the color, the more intense the waves.

So what can we make of these sounds? It turns out they pointed us to the strongest emission of energetic particles in the solar system, and we can use this to learn more about their origin.

“Jupiter is talking to us in a way only gas-giant worlds can,” Bill Kurth, research scientist at the University of Iowa and co-investigator for Waves, said according to Futurity. “Waves detected the signature emissions of the energetic particles that generate the massive auroras that encircle Jupiter’s north pole. These emissions are the strongest in the solar system. Now we are going to try to figure out where the electrons that are generating them come from.”

The Waves instrument will next take a measurement on November 2.

Quelle: OBSERVER

-

Mission Prepares for Next Jupiter Pass

› Full image and caption

Mission managers for NASA's Juno mission to Jupiter have decided to postpone the upcoming burn of its main rocket motor originally scheduled for Oct. 19. This burn, called the period reduction maneuver (PRM), was to reduce Juno's orbital period around Jupiter from 53.4 to 14 days. The decision was made in order to further study the performance of a set of valves that are part of the spacecraft's fuel pressurization system. The period reduction maneuver was the final scheduled burn of Juno's main engine.

"Telemetry indicates that two helium check valves that play an important role in the firing of the spacecraft's main engine did not operate as expected during a command sequence that was initiated yesterday," said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "The valves should have opened in a few seconds, but it took several minutes. We need to better understand this issue before moving forward with a burn of the main engine."

After consulting with Lockheed Martin Space Systems of Denver and NASA Headquarters, Washington, the project decided to delay the PRM maneuver at least one orbit. The most efficient time to perform such a burn is when the spacecraft is at the part of its orbit which is closest to the planet. The next opportunity for the burn would be during its close flyby of Jupiter on Dec. 11.

Mission designers had originally planned to limit the number of science instruments on during Juno's Oct. 19 close flyby of Jupiter. Now, with the period reduction maneuver postponed, all of the spacecraft's science instruments will be gathering data during the upcoming flyby.

"It is important to note that the orbital period does not affect the quality of the science that takes place during one of Juno's close flybys of Jupiter," said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. "The mission is very flexible that way. The data we collected during our first flyby on August 27th was a revelation, and I fully anticipate a similar result from Juno's October 19th flyby."

The Juno spacecraft launched on Aug. 5, 2011, from Cape Canaveral, Florida, and arrived at Jupiter on July 4, 2016.

JPL manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA's New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. Lockheed Martin Space Systems, Denver, built the spacecraft. Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages JPL for NASA.

Quelle: NASA

-

Update: 16.10.2016

.

NASA’s Juno spacecraft has a problem with its engine

Science not affected yet, but if problem isn’t fixed Juno will fly fewer orbits.

For NASA's Juno spacecraft, all had been going well since its July 4th insertion into orbit around Jupiter—as well as things can go when radiation is slowly eating away at a spacecraft, that is. That ended when mission managers tried to send a command to the robotic probe on Thursday.

According to a NASA news release, two helium check valves that play an important role in the firing of the spacecraft's main engine did not operate properly during the command sequence. "The valves should have opened in a few seconds, but it took several minutes," Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said. "We need to better understand this issue before moving forward with a burn of the main engine."

NASA had intended to fire the spacecraft's Leros 1b engine, its primary source of thrust, next Wednesday. The goal was to bring Juno into a shorter orbital period around the gas giant, from 53.4 to 14 days. The optimal time for such a "period reduction maneuver" is when the spacecraft is closest to the planet, so Juno's next opportunity for this engine burn will not come until Dec. 11. This was to be the final burn of the Leros 1b engine, which fired perfectly on July 4 to put Juno into a precise orbit around Jupiter. Future maneuvers can be conducted by smaller onboard thrusters.

Mission scientists emphasized that the longer orbital period would not affect the quality of science that Juno can collect as it flies close to the planet's poles. However, if the issue cannot be resolved, the spacecraft will not be able to make as many flybys as scientists hoped due to expected degradation of the spacecraft and its scientific instruments as it flies through Jupiter's harsh radiation environment. NASA hoped Juno would make 36 orbits during the next 20 months.

Quelle: arstechnica

-

Update: 20.10.2016

.

Newly released photo shows Jupiter's smiley face

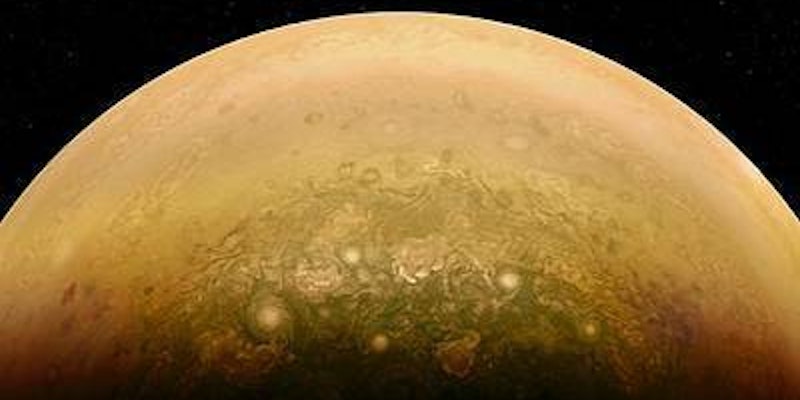

A new image, processed by a citizen scientist using data from a NASA spacecraft near Jupiter, shows the huge planet in a friendly new light.

While Jupiter — the largest planet in our solar system — is usually known for its immense gravity and extreme belts of hazardous radiation, the world looks distinctly happy, with a large smile in this new image created from data collected by NASA's Juno mission. Randy Ahn created the smiley photo by copying and flipping an image of a "half-lit" Jupiter, mirroring it on itself, according to NASA.

The new image was released as part of the agency's JunoCam initiative, which asks people to process raw images beamed back from Jupiter by Juno.

"The amateurs are giving us a different perspective on how to process images," Candy Hansen, JunoCam imaging scientist, said in a statement.

"They are experimenting with different color enhancements, different highlights or annotations than we would normally expect. They are identifying storms tracked from Earth to connect our images to the historical record. This is citizen science at its best."

Juno is also beaming back plenty of science in its own right, but the spacecraft — which reached Jupiter in July — recently ran into some snags.

Another citizen scientist-processed image of Jupiter.

IMAGE: NASA/JPL-CALTECH/SWRI/MSSS/ALEX MAI

Unexpected issues onboard

The spacecraft went into "safe mode" unexpectedly on Tuesday, when a monitor forced a reboot of Juno's computer after detecting something wasn't right. Because of that safe mode, the science instruments were turned off, and the spacecraft wasn't able to gather scientific data during a close flyby of Jupiter.

Mission controllers still aren't sure exactly why the spacecraft went into safe mode, but radiation doesn't seem to be the culprit.

“At the time safe mode was entered, the spacecraft was more than 13 hours from its closest approach to Jupiter,” Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager, said in the statement.

“We were still quite a ways from the planet’s more intense radiation belts and magnetic fields. The spacecraft is healthy and we are working our standard recovery procedure.”

NASA is also looking into another problem with Juno involving valves important to its propulsion system.

Last week, mission controllers put off an engine burn that would have brought Juno's orbit down to 14 days, instead of 53, but due to the issue, they decided to postpone.

It's not yet clear when or if engineers will decide to change Juno's orbit, but even if it does stay in the longer orbit for the rest of its mission, it will still be scientifically productive, according to Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton.

"The worst-case-scenario is I have to be patient and get the science slowly," Bolton said. If they have to stick to the 53-day orbit, "the science opportunities are all there," he added.

In spite of those setbacks, scientists are still working through analyzing data sent home from Juno gathered during its close flyby of Jupiter on Aug. 27.

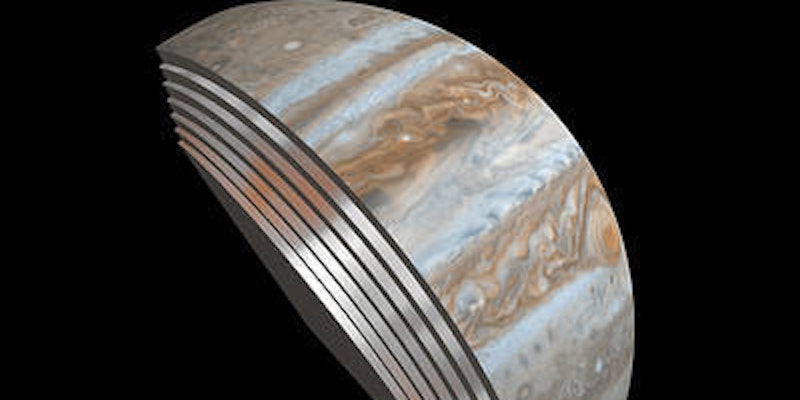

Scientists are starting to peer beneath Jupiter's cloud tops for the first time, checking out the layers below.

"We are seeing that those beautiful belts and bands of orange and white we see at Jupiter’s cloud tops extend in some version as far down as our instruments can see, but seem to change with each layer," Bolton said.

Juno also gathered data about the planet's strong magnetic field and its extreme auroras, but those discoveries are expected to be announced later this year.

Quelle: Mashable

-

Update:

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7309429/pia21107_secondary.0.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7424327/juno_burn-16b.0.jpg)