.

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA

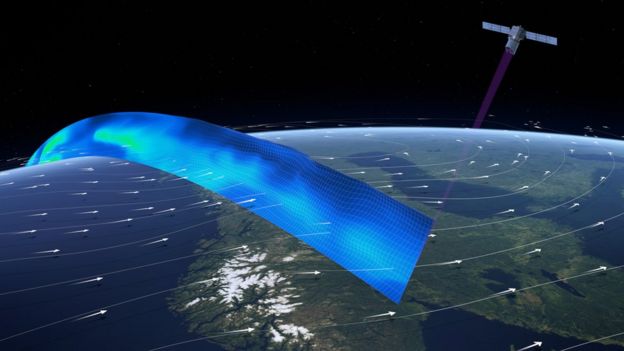

Europe’s Aeolus space laser mission, which is designed to make unprecedented maps of Earth’s winds, has reached a long-awaited key milestone.

Engineers at Airbus in the UK have finally managed to bolt together all the elements of the satellite after overcoming major technical challenges.

Aeolus is now set for several months of testing before being sent into orbit next year.

That will be 10 years on from the originally envisaged launch date.

“It’s been a long time coming but it’s a hugely important mission,” said Dr Ralph Cordey from Airbus.

“Operating lasers in space is not easy, but I’m pleased we’ve persevered with this technology in Europe because it has many potential applications, not just in measuring the wind."

The European Space Agency (Esa) has stuck with the project because of the nature of the data it will return.

It promises to give a big filip to weather forecasting. Even with the delays to the programme, the meteorological agencies still regard its information as a priority.

Image copyrightMAX ALEXANDER/AIRBUS DS

Image copyrightMAX ALEXANDER/AIRBUS DS

Aeolus carries a laser Doppler lidar, called Aladin, that will probe down through the atmosphere to see which way the wind is blowing and how fast.

Today, we have multiple ways of measuring the wind, from whirling anemometers and balloons to satellites that infer wind behaviour by tracking cloud movement or sensing the choppiness of the seas.

But these are somewhat limited indications, telling us what is happening in particular places or at particular heights.

Aeolus, on the other hand, will attempt to build a global, 3D view of the way the wind blows on Earth, from the surface of the planet all the way up through the troposphere into the stratosphere (from 0km to 30km).

The models used to forecast tomorrow’s weather will clearly benefit from this, but so too will the simulations that investigate future climate scenarios.

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA

Circling the globe, the satellite’s ultraviolet beam will pulse the air below it.

The time taken for the light to scatter back off molecules, dust and moisture particles will reveal where the big wind streams are in the atmosphere.

Small shifts in the frequency of the light will betray the speed at which those various markers - and the winds that carry them - are moving.

The concept is well established. Lasers like this are routinely fired into the sky from the ground to retrieve similar data at a single location.

The difficulty for Aeolus team has been in developing an instrument that will work in space. Esa approved the mission back in 1999 and contracted industry to start building it in 2003. That’s when the trouble started.

Installing a flush

The first problem was in finding diodes to generate a laser source with a long enough lifetime to make the mission worthwhile.

With that fixed, the mission looked in great shape until engineers discovered their laser system could not work in a vacuum - a significant barrier for a space mission. Tests revealed that in the absence of air, the laser was degrading its own optics.

Image copyrightAIRBUS DS

Image copyrightAIRBUS DS

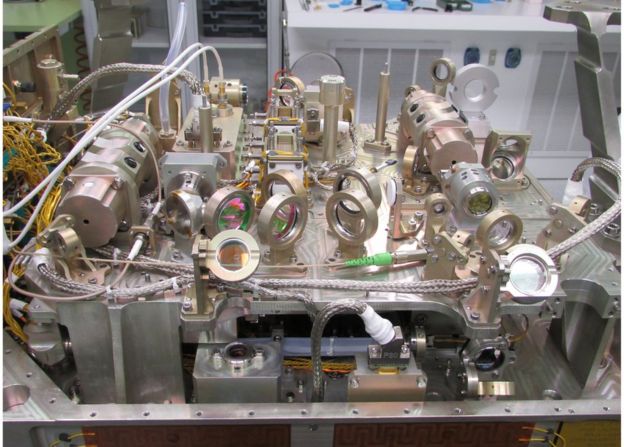

“Inside the instrument there are over 100 optical surfaces - lenses and mirrors to prepare the laser beam - and they were becoming contaminated,” explained Aeolus Airbus project manager Richard Wimmer.

“There were two sources of contamination. If there were particles on the optical surfaces, the laser would burn them and blacken the surfaces. But the laser was also dragging particles on to the surfaces that were outgassing from the spacecraft.”

The solution was to introduce a means to flush Aladin with oxygen at a very gentle rate. Its implementation has, of course, elongated the programme and added significant extra cost.

What was supposed to have been a €300m mission is now estimated at €450m.

'We'll be ready'

For many years, I would pass through the Airbus cleanroom in Stevenage and see the spacecraft bus - that part of the satellite which holds its computers, avionics, fuel tanks, and the like - sitting idly in the corner, waiting on experts in Italy (Leonardo) and France (Airbus) to solve the instrument issues.

But on Thursday, the British engineers were finally able to lower a completed Aladin laser instrument - together with the telescope it will use to spy the scattered light signal - on to the rest of the satellite.

Image copyrightAIRBUS DS

Image copyrightAIRBUS DS

The spacecraft must now undergo a series of tests prior to riding its Vega rocket into orbit next year.

Richard Wimmer has stayed with Aeolus throughout its trials and tribulations and was clearly delighted to see the full satellite come together.

“It’s one of those bizarre things where you wait and wait and wait, and then it comes and it seems like just another event. But it’s a major milestone for sure because now we’re on a more standard assembly, integration and testing sequence.

“We’ve got one very important and complex procedure to do in Liège in Belgium, where as well as putting the satellite in a thermal vacuum chamber we’ll also operate the whole instrument system and measure its performance. Then we’ll be ready.”

For Europe, Aeolus is an important step. The hard lessons learned are being applied to the next Esa laser mission called Earthcare, which will study the role clouds and atmospheric particles play in a changing climate.

But having this technology opens up other possibilities as well, such as making very precise surface height measurements. The Americans, for example, have done this with ice sheets and forest canopies.

Image copyrightMAX ALEXANDER/AIRBUS DS

Image copyrightMAX ALEXANDER/AIRBUS DS

Today, ESA and Arianespace signed a contract to secure the launch of the Aeolus satellite. With this milestone, a better understanding of Earth’s winds is another step closer.

The contract, worth €32.57 million, was signed at ESA headquarters in Paris, France, by ESA’s Director of Earth Observation Programmes, Josef Aschbacher, and CEO of Arianespace, Stéphane Israël.

Josef Aschbacher said, “Aeolus has certainly had its fair share of problems. However, with the main technical hurdles resolved and the launch contract now in place, we can look forward to it lifting off on a Vega rocket from French Guiana, which we envisage happening by the end of 2017.”

Carrying pioneering ultraviolet lasers, never before flown in space, Aeolus will provide slices through the world’s winds along with information on aerosols and clouds.

This will not only advance our knowledge of atmospheric dynamics, but also provide much-needed information to improve weather forecasts.

As part of the Earth Explorer series, it has been developed to contribute to our understanding of the way Earth works and how human activity is affecting the delicate balance.

While the mission responds to the needs of the scientific community, it will also demonstrate cutting-edge technology that could pave the way for new ways of observing our planet and future applications of Earth observation data.

In fact, Aeolus will be the first satellite to provide profiles of the wind on a global scale. To do so it carries one of the most challenging pieces of space technology ever developed: the Aladin wind ‘lidar’ – a laser form of radar.

Several years in the making, this state-of-the-art instrument houses two powerful lasers, a large telescope and very sensitive receivers.

The laser generates ultraviolet light that is beamed towards Earth. This light bounces off air molecules and small particles such as dust, ice and droplets of water in the atmosphere. The fraction of light that is reflected back to the satellite is collected by Aladin’s telescope and measured.

The movement of the air molecules, particles or droplets cause this reflected light to change frequency slightly. By comparing the frequencies returned from various altitudes with the original laser, the winds below the satellite can be determined.

Despite numerous setbacks developing it, recent tests show that Aladin is now up to the demanding task that lies ahead.

With these development problems resolved, engineers at Airbus Defence and Space in Stevenage, UK, are now busy adding the instrument to the satellite. Once Aeolus is complete and thoroughly tested, the satellite will be prepared for shipping to Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana.

Vega rockets can place 300–1500 kg satellites into low orbits. The first ESA Earth observation satellite to be taken into orbit on a Vega was Sentinel-2A in 2015.

Quelle: ESA

---

Arianespace chosen by ESA to launch ADM-Aeolus (Atmospheric Dynamics Mission) satellite with Vega in 2017

The ADM-Aeolus launch contract was signed by the European Space Agency’s Director of Earth Observation Programmes Josef Aschbacher (at left) and Arianespace Chairman and CEO Stéphane Israël (right), in the presence of ESA Director General Jan Woerner. Photo: ESA–Nadia Imbert-Vier, 2016

Arianespace has signed a contract with the European Space Agency (ESA) to launch the ADM-Aeolus satellite, a key mission within the scope of Europe’s Earth Explorer program.

ADM-Aeolus will provide global observations of 3D wind profiles from space, enabling scientists to refine the currently known characteristics and improve techniques for modeling and analyzing the Earth’s atmosphere. This mission will make a direct contribution to improving the quality of weather forecasts and climatology research. The ADM-Aeolus mission is named after the mortal designated by the gods in Greek mythology as the keeper of the winds.

ADM-Aeolus will weigh about 1,400 kg at launch, and will be injected into Sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of 320 km. It comprises three modules:

- Aladin (Atmospheric Laser Doppler INstrument), a direct-detection lidar (a laser “radar”) incorporating measurements of scattering from aerosols and water droplets (“Mie”) and molecular scattering (“Ray-leigh”), to provide 3D images of wind profiles.

- A platform based on that used for the Mars Express spacecraft.

- Solar array.

Airbus Defence and Space is prime contractor for the ADM-Aeolus mission, and is also in charge of the Aladin in-strument.

The satellite will be launched from the Guiana Space Center, Europe’s spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, during the second half of 2017, using a Vega light launch vehicle.

Following the contract signature, Stéphane Israël, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Arianespace, said: “We are both proud and honored to be chosen once again for a European space mission, which will make a major scientific contribution to our planet. I would like to extend my warm thanks to ESA’s Earth observation directorate for their expression of trust. This latest contract is further recognition of the quality and reliability of the launch services offered by Arianespace and our light launcher, Vega.”

About Arianespace

To use space for a better life on earth, Arianespace guarantees access to space transportation services and solutions for any type of satellite, commercial as well as institutional, into any orbit. Since 1980, Arianespace has placed more than 500 satellites into orbit with its three launchers, Ariane, Soyuz and Vega, from French Guiana in South America, and from Baikonur, Kazakhstan (central Asia). Arianespace is headquartered in Evry, France near Paris, and has a facility at the Guiana Space Center in French Guiana, plus local offices in Washington, D.C., Tokyo and Singapore.

Quelle: arianespace

-

Update: 1.02.2017

.

WIND SATELLITE HEADS FOR FINAL TESTING

The road to realising ESA’s Aeolus mission may have been long and bumpy, but developing novel space technology is, by its very nature, challenging. With the satellite now equipped with its revolutionary instrument, the path ahead is much smoother as it heads to France to begin the last round of tests before being shipped to the launch site at the end of the year.

Aeolus carries one of the most sophisticated instruments ever to be put into orbit: Aladin, with two powerful lasers, a large telescope and very sensitive receivers.

It shoots pulses of ultraviolet light down into the atmosphere to profile the world’s winds.

This is a completely new approach to measuring the wind from space, which usually involves tracking cloud movement, measuring the roughness of the sea surface or inferring wind from temperature readings.

Aeolus has been built mainly to advance our understanding of Earth. These vertical slices through the atmosphere, along with information on aerosols and clouds, will advance our knowledge of atmospheric dynamics and contribute to climate research.

However, Aeolus also has a very important practical role to play because its measurements will be delivered rapidly, improving weather forecasts.

After its long development, Aladin was finally ready to join the satellite at Airbus Defence and Space in Stevenage in the UK in August last year.

ESA’s Aeolus project manager, Anders Elfving, said, “Over the last months, the UK team with support of their colleagues from Toulouse in France have worked tirelessly to integrate Aladin into the satellite, to check that all is aligned and that the complete satellite is working flawlessly.”

With the satellite now complete, it is time move it to Toulouse where it will be tested to make sure that it can withstand the vibration and noise of liftoff.

“This next round of tests is very important and I know the team is raring to get the opportunity to show that their proudly built satellite can withstand the tough ride on the launcher,” added Anders.

After this, Aeolus will go to Liege in Belgium to be checked in a thermal–vacuum chamber.

Anders said, “We still have some critical steps ahead. We need the ultimate proof that the laser and the complex optical system performs well with the satellite thermal radiators and in vacuum conditions, but I am confident that the satellite, operation and launch teams will deliver as planned.”

Once all this is done, towards the end of the year, it will be shipped across the Atlantic to Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana for launch on a Vega rocket.

Quelle: ESA