-

NASA Curiosity Team Pinpoints Site for First Drive, First Laser Use On Tap This Weekend

WASHINGTON -- The scientists and engineers of NASA's Curiosity rover mission have selected the first destination for their one-ton, six-wheeled mobile Mars laboratory. The target area, named Glenelg, is a natural intersection of three kinds of terrain. The choice was described by Curiosity Principal Investigator John Grotzinger of the California Institute of Technology during a media teleconference on Aug. 17.

"With such a great landing spot in Gale Crater, we literally had every degree of the compass to choose from for our first drive," Grotzinger said. "We had a bunch of strong contenders. It is the kind of dilemma planetary scientists dream of, but you can only go one place for the first drilling for a rock sample on Mars. That first drilling will be a huge moment in the history of Mars exploration."

The trek to Glenelg will send the rover 1,300 feet (400 meters) east southeast of its landing site. One of the three types of terrain intersecting at Glenelg is layered bedrock, which is attractive as the first drilling target.

"We're about ready to load our new destination into our GPS and head out onto the open road," Grotzinger said. "Our challenge is there is no GPS on Mars, so we have a roomful of rover-driver engineers providing our turn-by-turn navigation for us."

Prior to the rover's trip to Glenelg, the team in charge of Curiosity's Chemistry and Camera instrument, or ChemCam, is planning to give their mast-mounted rock-zapping laser and telescope combination a thorough checkout. On Saturday night, ChemCam is expected to "zap" its first rock in the name of planetary science. It will be the first time such a powerful laser has been used on the surface of another world.

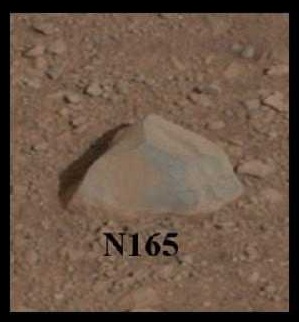

"Rock N165 looks like your typical Mars rock, about three inches wide. It's about 10 feet away," said Roger Wiens, principal investigator of the ChemCam instrument from the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. "We are going to hit it with 14 millijoules of energy 30 times in 10 seconds. It is not only going to be an excellent test of our system, it should be pretty cool too."

Mission engineers are devoting more time to planning the first roll of Curiosity. In the coming days, the rover will exercise each of its four steerable (front and back) wheels, turning each of them side-to-side before ending up with each wheel pointing straight ahead. On a later day, the rover will drive forward about one rover-length (10 feet, or 3 meters), turn 90 degrees, and then kick into reverse for about 7 feet (2 meters).

"There will be a lot of important firsts that will be taking place for Curiosity over the next few weeks, but the first motion of its wheels, the first time our roving laboratory on Mars does some actual roving, that will be something special," said Michael Watkins, mission manager for Curiosity from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Quelle: NASA

-

On Saturday night, Curiosity is due to use its laser blaster for the first time, taking 30 shots at a poor little rock known as N165. In the coming days, the rover also will analyze the rocks that have been exposed at a blast mark known as Goulburn Scour, which was left behind by Curiosity's rocket-powered sky-crane descent stage during the Aug. 5 landing. And it will take its first test drive, going about 10 feet (3 meters) to limber up for its first long-distance journey.

-

-

A photo from the Curiosity rover's Mastcam imaging system shows rover hardware in the foreground and highlights the location of a rock known as N165, which is the first target for the ChemCam laser zapper.

'Target practice' for laser zapper

The mission's purpose is to analyze Martian rock and soil to determine whether the planet's chemistry could have supported life in Mars' ancient past, when the planet was wetter and warmer than it is today. The car-sized, 1-ton Curiosity rover has 10 scientific instruments to do the job — including its ChemCam imaging system, which incorporates a laser powerful enough to vaporize tiny spots of rock.

N165, a 3-inch-wide (7.5-centimeter-wide) rock sitting on the ground about 10 feet (3 meters) from the rover, would be the first target for the laser zapper, said Roger Wiens, a planetary scientist from Los Alamos National Laboratory who is the ChemCam team's prinicipal investigator. About 30 laser blasts would be aimed at the rock over the course of 10 seconds.

"This is sort of target practice, if you will," Wiens said.

Each 14-millijoule laser pulse briefly focuses the energy equivalent of a million light bulbs onto an area the size of a pinhead. The flashes of light given off by the mini-blasts of plasma are captured by ChemCam's imaging system and routed through fiber optics to a spectrometer inside the rover. By checking the spectrum of the light, scientists can figure out the composition of the material vaporized by each zap.

Wiens said he expected N165 to be the kind of garden-variety basalt rock typically found on Mars. He and his colleagues are more interested in finding out whether ChemCam can discriminate between the rock's dusty coating and the minerals beneath the coating. That's why the rock is being blasted so many times in succession. The first results could be revealed early next week, Wiens said.

"Our team has waited eight long years to get to this date," Wiens said.

Instruments coming to life

Grotzinger said the checkouts for all of Curiosity's scientific instruments are going well. Just today, the neutron-generating device known as DAN (Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons) was turned on while another instrument called RAD (Radiation Assessment Detector) monitored the radiation that DAN was giving off, he said.

The rover's weather station, dubbed REMS (Rover Environmental Monitoring Station), is already providing temperature readings: Grotzinger said the high temperature on Mars over the past day was just above freezing (276 Kelvin, which is 37 degrees Fahrenheit or 2.85 degrees Celsius).

"It's been exactly 30 years since the last long-duration-monitoring weather station was present on Mars," he said. "That was when the Viking 1 lander stopped communicating with the earth. That was back in 1982, so 30 years later we're happy to be on the surface doing that monitoring again."

The instrument checkout should be complete "toward the end of next week," Grotzinger said. At one time, he had suggested that the blast marks left behind by the descent stage, just yards away from the rover's landing site, might be a good first target for detailed sampling. But today, Grotzinger said that the exposed bedrock at Goulburn Scour appeared to be a loosely held-together combination of material. "This rock is really not a good one for the first drilling," he said.

So instead, scientists will examine the blast marks with Curiosity's cameras, perhaps including ChemCam, and then most likely move on. The blast marks have been given names that reflect their fiery genesis: Goulburn, Burnside, Hepburn and Sleepy Dragon. "The theme here is heat," Grotzinger said.

The first samples could well be scooped from the Martian surface at some point between the landing site, which is in a quadrant that's been nicknamed Yellowknife, and the Glenelg site, Grotzinger said. Those samples could be ground up and deposited into a couple of onboard chemical laboratories called CheMin and SAM (which stand for "Chemistry and Mineralogy" and "Surface Analysis at Mars," respectively). "That first scooping activity is really important," Grotzinger said.

Quelle: NASA+NBC-News