.

24.04.2016

Missile tests stand up Alaska Aerospace business

North Korea dictator Kim Jong-un tested his new intercontinental ballistic missiles twice in July.

It was his way of showing the world he has a big one. Both times events in Alaska deflated him, at least a bit.

Kim’s first test was July 4 and his second on July 29. The U.S. fired off a test missile interceptor July 10 from Kodiak’s Pacific Spaceport with a second interceptor launched July 30, one day after Kim fired off his second test ICBM.

Both interceptors from Alaska hit their ballistic missile targets high above the Pacific Ocean. They were fired by U.S. Army units from the Kodiak launch facility, which is owned and operated by the state-owned Alaska Aerospace Corp.

It wasn’t really tit-for-tat with Kim Il-Sung, of course. The coincidence of the dual interceptions, both shortly after Kim launched his missiles, delighted Americans and sent a message to the North Korean dictator.

But the Alaska tests, involving the U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense, or THAAD, system, were actually planned a year ago by the U.S. Missile Defense Agency, according to Craig Campbell, CEO of Alaska Aerospace, who spoke July 26 at a World Trade Center Anchorage lunch event.

Still, Kim’s aggressive testing has lent an urgency to the U.S. missile defense program and focused new attention on Alaska’s role in it. U.S. missile defense interceptors aimed at intercepting intercontinental ballistic missiles in “mid-course,” high in their trajectory while in space, are already based at Fort Greely, east of Fairbanks.

Long-range radar systems that would detect enemy missiles are at Clear Air Force Station, southwest of Fairbanks.

Upgrades and expansions at both installations were underway even before North Korea launched its latest missile program, but these will now be accelerated.

Alaska’s U.S. Sen. Dan Sullivan was able to get amendments into this year’s National Defense Authorization Act that would authorize 28 additional ground-based interceptors as well as development of new missile defense sensor technologies that would function in space.

Sullivan’s amendment includes a study of installation of up to 100 interceptor missiles at locations across the U.S.

The Alaska senator had previously introduced a bill expanding the interceptor program, co-sponsored by a bipartisan group of 25 senators, but he wound up being able to incorporate 85 percent of the bill in a series of amendments to the defense appropriation bill.

Kim’s missiles, however, have also extended a lifeline to the Alaska spaceport at Kodiak, which had been struggling. When the state formed the then-Alaska Aerospace Development Corp., or AADC, and built the Kodiak launch complex in the early 1990s, the goal was always to primarily service commercial space companies by offering an alternative, lower-cost launch site to the big government-owned launch centers at Cape Canaveral in Florida and Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

The commercial space industry didn’t develop as quickly as expected, however, but the state was able to keep the lights on at its Kodiak facility by launching test missiles in the early stages of the U.S. missile defense program as well as for other government agencies. There were a handful of commercial launches too, including some that put satellites into orbit.

But the launches weren’t frequent enough, and by 2012 the future looked uncertain for the state’s space venture.

“We can’t pay the bills with just one launch every 12 to 18 months,” said Campbell, who came aboard at AADC in 2011 and became its president of in 2012.

Campbell, a former state adjutant general and lieutenant governor, moved to inject new life into the state corporation. For starters, the name changed, removing “development,” so that it became the Alaska Aerospace Corp.

It was an important distinction.

“We did this because we are really an operations, not a development organization,” Campbell said.

Having “development” in the name conveyed a message that the state corporation was still developing when, in fact, it had long proved itself as a capable manager of launch operations.

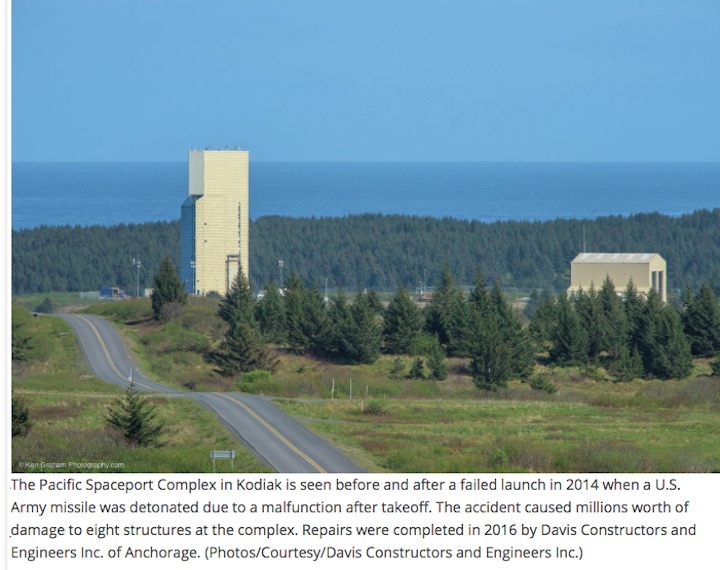

The Kodiak Launch Complex was also renamed Pacific Spaceport Complex to bring more attention to its location and access to a wide area of the North Pacific, with no populated areas, across which launches can be made safely.

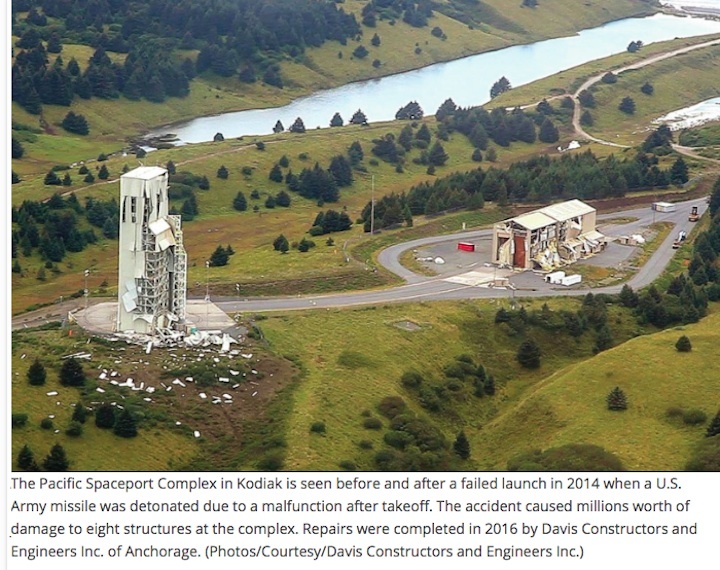

There was some really bad luck in 2014, however. An Army test missile malfunctioned just after it launched and had to be destroyed, but debris from the explosion caused heavy damage at the Kodiak facility.

It seemed like the end of the road.

“The launch itself was flawless. The problem was in the missile itself,” Campbell said.

Alaska Aerospace was still without customers, however, and it now had a damaged launch facility. To top it off, in 2015 Gov. Bill Walker had to cut the small amount of state general fund support for the corporation as the state faced an implosion of its oil revenues.

Extensive repairs to the Kodiak facility totaling $35 million were largely paid for through the company’s insurers. Campbell wrote via email that as a state-owned corporation the complex was covered through the state insurance pool.

The repairs were completed in 2016 with $20.3 million worth of work completed by Davis Constructors and Engineers Inc. of Anchorage and the launch complex was back in business.

Meanwhile, Campbell and his crew hustled for contracts.

“Things were looking grim, but we went out with an aggressive marketing effort,” Campbell said.

AAC returned to a former prime customer, the Missile Defense Agency, and opened an office in Huntsville, Ala., where the MDA is headquartered.

The initiative paid off with an $80.4 million multi-year “task order” from the agency, a kind of purchase order to cover launch activities. The two THAAD tests in July were part of that.

More missile defense tests will likely happen and the timing if those is confidential. One that is officially set for next summer, however, is a test of a modified Israeli “Arrow” interceptor, a joint Israel-U.S. test program.

The Arrow 3 is a modified version of Arrow 2, which Israel has long used.

“Arrow 3 is a longer-range version and it needs a bigger test range. But you can’t just launch these over the Mediterranean Sea,” Campbell said.

The wide expanse of the Pacific south of Kodiak provides the space, he said.

MDA has brought breathing room for Alaska Aerospace, with funding to cover operations and maintenance until the commercial business picks up. That’s now happening, Campbell said.

Alaska Aerospace has strategically targeted a fast-emerging niche of the commercial space business, companies launching small rockets, typically with small satellites.

These firms need a lower-cost alternative to the big U.S. government launch sites, and also ones that can offer flexibility in scheduling because military and large commercial users dominate the schedules of Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg.

There are now several places in the world that can offer this, New Zealand for example, but few are in the U.S., an important factor for certain customers, Campbell said.

One commercial contract that is signed and scheduled for December is with a new space company that cannot now be identified, Campbell said.

Interestingly, this will be the first launch from Kodiak of a rocket using liquid fuels. All other rockets have been solid-fueled.

“This will require us to design and install facilities to handle liquid fuels,” with fuel storage and piping, as well as planning additional safety measures, Campbell said.

Once the liquid fuel systems are installed, the Kodiak facility will offer customers the option of using liquid-fueled rockets, which are typically less costly and more attractive to commercial customers. The military typically uses solid fuel rockets.

Vector Space Systems, an Arizona-based company formerly known as Garvey Spacecraft, has also signed with Alaska Aerospace for test flights of its new Nanosat Launch Vehicle, the Vector-R, in 2018.

A contract that still in negotiation for launches planned in 2018 and 2019, is with Rocket Lab USA, a California-based company that has been in the space business for several years.

Alaska Aerospace supported Rocket Launch earlier this year in a launch by the company in New Zealand; the Alaska corporation provided its mobile range safety and telemetry equipment in support of Rocket Lab, moving the equipment to New Zealand.

Rocket Lab now wants to use Kodiak for launches of its new “Electron” rocket, Campbell said.

Another company in discussions for launches in 2019 is Zero Point Frontiers, based in Alabama, for its 55-foot Xbow Launch Vehicle that will launch small satellites to orbit.

Interestingly, Zero Point Frontiers would use a rail-launch system it has developed for its small rockets, an alternative to the traditional vertical launch of rockets from a pad. Alaska Aerospace will be involved in helping design and install this, Campbell said. Once the system is installed it will remain in Kodiak, giving the Pacific Spaceport another new capability.

Also, some companies negotiating with Alaska Aerospace want an ability to put satellites in an equatorial orbit, which is more easily done from a launch site at a more southerly latitude than Kodiak, which is more suited to launches to polar orbits for satellites.

Alaska Aerospace is now investigating possible sites for alternative southern launch locations in the Pacific, one at Saipan and the other on Hawaii, the biggest of the Hawaiian Islands, Campbell said.

Quelle: Alaska Journal