.

Thanks to a new book, these female pioneers who helped the U.S. win the space race are finally getting their due

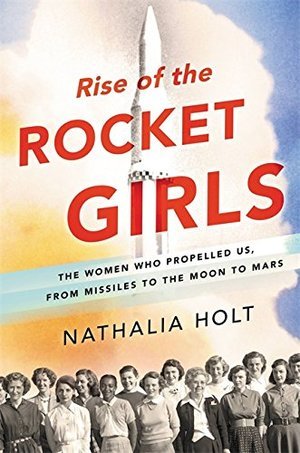

The women "computers" pose for a group photo in 1953. (Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech)

.

It’s rare that a scientist’s name becomes a household one, no matter how great his or her discovery is. And yet, a handful of brilliant American innovators in rocket science still enjoy name recognition: Werner Von Braun, Homer Hickman, Robert Goddard, among them. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, is where many of the brightest rocket scientists collaborated on the early achievements of the space program, and JPL’s website is quick to hail the men behind the missions. Even lesser-known figures, such as Frank Malina, Jack Parsons and Ed Forman, who founded the lab in the 1930s, are remembered fondly as “rocket boys” and “rocketmen.” What’s missing from an otherwise detailed history online, however, is major part of the story: the rocket girls.

When biologist and science writer Nathalia Holt stumbled, serendipitously, upon the story of one of NASA’s first female employees, she was stunned to realize that there was a trove of women’s stories from the early days of NASA that had been lost to history. Not even the agency itself was able to identify female staffers in their own archival photographs.

Preview thumbnail for video 'Rise of the Rocket Girls: The Women Who Propelled Us, from Missiles to the Moon to Mars

Rise of the Rocket Girls: The Women Who Propelled Us, from Missiles to the Moon to Mars

Based on extensive research and interviews with all the living members of the team, Rise of the Rocket Girls offers a unique perspective on the role of women in science: both where we've been, and the far reaches of space to which we're heading.

Holt took on the cause and was ultimately able to find a group of women whose work in rocket science dates back to before NASA even existed. In her new book Rise of the Rocket Girls, Holt documents the lives of these women, who were not only pioneers in their profession, but also in their personal lives. The “rocket girls” worked outside of the home when only 20 percent of women did so, had children and returned to work, went through divorce when it was first becoming socially accepted, and witnessed the first wave of feminism, not to mention other social revolutions in the decades that spanned their careers.

Holt spoke to Smithsonian about discovering this lost chapter of history, the choices she made in how to tell their stories, and the state of women in the sciences today.

The book came about when you discovered a special connection to one of the women that you researched, Eleanor Frances Helin. Can you tell that story?

In 2010, my husband and I were expecting our first baby and we were having an incredibly difficult time coming up with names. We were thinking about “Eleanor Frances,” so I Googled the name, as you do these days to make sure there isn’t anything bad out there. The first picture that came up was this beautiful picture in black and white of a woman accepting an award at NASA in the 1950s. It was very shocking to me that there were women who were part of NASA during this time. I had never heard of them.

I found out more about Eleanor Frances. She had an amazing career at NASA. She discovered many meteors and comets. But one of the most surprising things to me was that she wasn’t alone. She was one of many women that worked at the space agency, and so it was because of her that I found out about this really incredible group of women that were at NASA right from the beginning.

I didn’t know I was going to write a book. I just became very interested in who these women were. When I started contacting the archives and going through records at NASA, I found that they had these wonderful pictures of women who worked there during the 1940s, the 1950s, and on through today, yet they didn’t know who the women in the pictures were. They couldn’t identify them, and they had very little contact information at all for anyone from that time. It ended up being quite a lot of work just to hunt down the right women. Once I did find a few of them, it became easier. They’re a group of women who worked together for 40, 50 years and they’re still friends today.

I’m very grateful that we named our daughter Eleanor Frances, who unfortunately passed away a year before our Eleanor was born, but she was a really inspiring person. It would have been nice for her to make a bigger appearance in the book, but it focuses on the core group of women who started out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) right from the beginning and worked as “computers,” and on how they became the first female engineers at the lab.

The chapters incorporate not only the women’s professional trajectories and accomplishments, but also detail their personal lives, especially their relationships with spouses and partners. How did you balance the science part of the story with those humanizing, personal anecdotes?

In the beginning, I was worried that spending too much time talking about their lives would somehow detract from their contributions, but I wanted to make sure the book was about the women. We’ve had many books that have looked at the early days of NASA, and so I wanted to make sure that I was really celebrating what they did. What I found as I was writing it is that so much of what they were working on at the time mirrored things that were happening in their lives.

One great example I feel like was when they were working on Jupiter-C, an early frontrunner to the first American satellite. This project could have beaten Sputnik possibly, certainly the women feel like that could have happened, but much of it was held back for political reasons. The women had these positions where they were incredibly skilled mathematicians, and yet they weren’t being given full credit and the full ability to show what they could do.

In 1960, only 25 percent of mothers worked outside of the home. So it is important to celebrate the fact that these women were able to have these careers where they had to work a lot of late nights and had very demanding jobs and were really part of the science at JPL – and also we have these stories of them trying to balance their home lives. I think it's very relatable for women and mothers today no matter what your profession is or what you're doing. There's something about seeing that struggle in the ’50s and ’60s and comparing it to today.

Your book opens with the story of the launch of Explorer I, the first American satellite to go in orbit, and closes with the 50th anniversary of that event, in which two of the “Rocket Girls” are excluded. Why did you choose to frame the whole book that way?

The book, overall, is a joyful story because these women ended up having incredibly long careers and getting many of the achievements that they really strived for, but they did not necessarily get the recognition. There are some very sad parts in the book, where you have these two women who were in the control room, who were a vital part of the first American satellite, who were not invited to the big celebration 50 years later.

Despite how much they were able to accomplish and what a vital part they played, their stories were lost to history. Of course, it isn’t just them. There are scientists all over who played a vital role in our lives but haven't gotten the recognition they deserve. This happens to women scientists in all areas. Though, I feel right now like there's a lot of attention. People are interested to learn more about these turning points in history and more about the women that were part of them. So it was important to me, in writing this book, to try to bring as much attention as I could to what these women did because it's incredible. When you look at what they did in these 50-year careers, the number of missions they were part of, it's amazing and inspiring.

In one section, there is a passage in which the women “bristled at the term” “computresses” and called themselves “the sisterhood.” Later, you write that they weren’t called “engineers” until 1970. Can you talk about the ways these women labeled themselves and thought about their role in space research, as opposed to how men or the outside world thought of them?

I was very struck when I first found out that these women were called computers. Of course today we think of computers as devices, so it was interesting to me that there were many, many people, men and women, who worked as computers. Many of the male engineers I spoke to, who worked with the women, called them computresses. It just sounds horrible, and that's certainly how the women felt about it. They hated being called that.

So to overcome that, they gave themselves their own names. They called themselves “Helen's Girls” for a long time because of one very influential supervisor named Helen Ling. Helen did an incredible job bringing women into NASA and was a powerhouse in bringing women engineers into the laboratory. They also called themselves the sisterhood because they were a close group that supported one another. They were really there for one another, and you can see that in the way that they went and had kids and came back: They looked out for each other and made phone calls to make sure women were coming back after having kids. It was a really special group. They really enjoyed each other's company and they really loved their careers at JPL.

It's a big turning point in the book when they become engineers, when they finally get the label they deserve, and, of course, the increased pay that comes with that. Although it didn’t change everything: In the book, I talk about Susan Finley, who is NASA's longest-serving woman. She doesn't have a bachelor's degree, which many of the women didn’t. A few years ago, NASA changed some of the rules, and if you did not have a bachelor's degree, then you had to be an hourly employee, you couldn’t be a salaried employee. And so they actually changed her pay. It was really shocking to me that this kind of thing would happen to someone to who's been there since 1958. It ended up that she was getting so much overtime that they changed the rule for her, so she is on salary now and she's doing fine.

Today, around 18 percent of American engineering students are women, and only 13 percent of engineers working in the U.S. today are women. Can you talk about if and how the field has changed, and how these women set some of that into motion or helped other women who came after them?

The number of women graduating with degrees in computer science has actually fallen in the last 20 years quite significantly. This is a problem. I feel that what Helen did [in keeping women in the lab] is remarkable. You have women not only not pursuing degrees in science and engineering and tech, but even when they do get degrees, you often have women dropping out of the career. Half of all women in STEM fields leave their jobs mid-career. We talk about the problem of sexual harassment in science. We talk about problems of sexism. There are many ideas of what might be going on.

What I really like about this group of women is not just all that they accomplished at a time when they had to deal with difficult sexual harassment and many challenges, but what they found: that by being this group of women with a female supervisor, they were really able to advocate for each other. And there's actually been a lot of research that supports this. Researchers have found that when you have a gender balance in a specialty that tends to be a male dominated field, it reduces sexual harassment for both men and women.

There are some devastating moments when pregnancies or motherhood threaten their careers. Then at one point, JPL lets the women change their working hours to accommodate childcare. The book acts as a fascinating time capsule, capturing what it was like to be a working woman at a time when only 20 percent of women worked outside the home, or when a woman could be fired simply for being pregnant. How did these women make it work?

The institutional policies at JPL were key for this group of women having the long careers that they did. You can see that when you look at what was happening at other NASA centers at the time. They also had groups of computers, many of them women, many of them hired after WWII. (During WWII, there were not enough men to take these jobs, so you had women mathematicians that were able to get in the door at these centers all over the country.) But [despite the circumstances], at these centers, they did things very differently. Many had very strict schedules. The women had to work 8-hour days, they had set breaks, many of them didn’t allow women to talk to one another, they had to work in complete silence. These policies are not only not family-friendly, they're really just not friendly at all. Who would want to work under these conditions?

JPL was always different. It was founded by this crazy group of people called the “suicide squad,” who were trying to push the limits and do crazy experiments. So even though it was an Army lab, it always had this association with Caltech and this university culture that was very different. And because of that, you see a difference in what happened to the women who were computers at JPL. For them, it was never about a set number of hours. It was about getting the job done. They were able to come in earlier in the morning when they needed to, there were times when they had to work all night, they had to work all kinds of crazy hours during missions, but then they were able to modify their hours at other times when they had family needs.

It was also a very social place where they had parties and beauty contests. That seems ridiculous by today's standards, and yet for the women that were part of it, it actually ended up fostering relationships between the women and the men that they worked with. Because of that, many of these women were included on scientific publications that were authored by the men. During that time, it was very unusual for women to be included on these publications. And so these social activities could end up bolstering their careers quite a bit. Many of these factors made JPL a unique place, and really made it ideal for them.

Some of the women were also pioneers in a different kind of domestic arena: divorce. How did various social changes impact the women and their work?

Social changes permeated their culture everywhere. One of these is divorce, one of these is the birth control pill, another is the rise of feminism. These are all really interesting points that impact what's happening with NASA, with our women, and with Margaret Behrens in particular. It is heartbreaking to see her marry so young and be in this horrible marriage. She ends up getting out of it and coming back to the lab, and things change for the better, but it was such a difficult time for her. She really felt like she was the only person in the world getting divorced, even though at that time, divorce rates were going way up.

Sylvia Lundy, too, goes through an experience like this, and it's reflected in the other things happening in her life. She becomes a very important engineer at JPL, directing the Mars program office, and experiencing losses with some of the missions that she wishes were funded. It sounded like a similar emotion, when I spoke with her about it, that she felt about divorce. It's interesting how loss can sometimes feel the same when you're so invested in the science that you're doing.

For the most part, the women had so many different types of experiences. You have women in long, happy marriages, but that had really no family support nearby and felt stranded sometimes. There were women who had strained relationships. There were women who had a lot of family nearby and were able to figure out childcare very easily because of that. There were all different kinds of relationships going on in these women’s lives, and yet they all worked together and were able to make it work. It’s inspiring.

As recently as 1974, the men and women of JPL worked in separate buildings. Can you talk about some of the specific aspects of sexism and gender segregation these women encountered?

All of the women were in one building, and all of the men were in the other, which seems so crazy by today's standards. Many of the men who worked at JPL at the time, though they weren't making decisions about which offices people worked in, look back and have regrets about how things were done. They kind of can’t believe this is the way that the women were treated, that they weren’t treated as equals during that time. They can look back with some perspective.

And many of them, at the time, were trying to change things right along with the women. It wasn’t like the women were out there alone trying to change their positions. Many of the men were trying to change how the women were involved in decision making, how they were brought in on projects, and how they were put on papers.

The men and women working in different buildings was one thing. The beauty contests, as I mentioned before, were just ridiculous. One of the women, Barbara Paulson, was in the contest when it was Miss Guided Missile. When I went through these pictures, it seemed so absurd. But the interesting thing was that when I talked to her about it, she really felt that this was never about how you looked. It was more just a fun social moment, and it was about popularity. She was the second-runner-up which was a big deal, she got to ride in a convertible around the lab and wave at all her colleagues, and then she was made supervisor just a few years later. So as absurd as all of this seems, there are parts of it that were surprisingly helpful to them.

How can we do a better job bringing women and girls into the hard sciences?

Numerous studies have found that role models are key to increasing underrepresented groups into the sciences. When young people see scientists who look like them, it makes the dream of pursuing careers in STEM attainable. Bolstering the presence of women scientists in education is critical and my hope is that by shedding light on the groundbreaking women of NASA, young women will find in their stories a reflection of themselves and what they aspire to be.

Quelle: Smithsonian

4434 Views