.

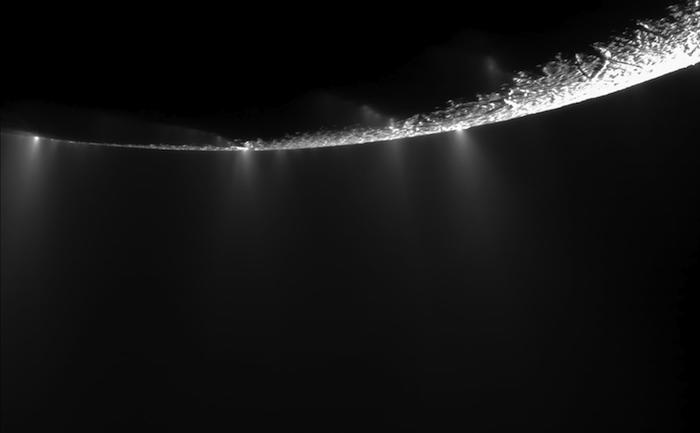

Plumes erupting off the surface of Enceladus, an icy moon. Credit: NASA/JPL/SSI

-

How acidic is the ocean on Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus? It’s a fundamental question to understanding if this geyser-spouting moon could support life.

Enceladus is part of a family of icy worlds, including Europa (at Jupiter) and Titan (also at Saturn), populating our outer solar system. These bodies are some of the most promising places for life because they receive tidal energy from the gas giants they orbit and some contain liquid water.

The Cassini spacecraft has been taking regular measurements of Enceladus for more than a decade to evaluate its environment. One of the key factors influencing the habitability of an environment is its chemical composition, in particular its pH. On Earth, it’s possible for life to exist near the extremes of the pH scale that ranges from 0 (battery acid) to 14 (drain cleaner). Knowing the pH can help us to identify geochemical reactions that affect the habitability of an environment, because many reactions cause predictable changes in pH.

Oceanography of another world

While we cannot stick a strip of pH paper into the ocean water on Enceladus to measure the pH directly, it can be estimated by looking at molecules in its plumes that change form in response to pH changes.

Recently, geochemist Christopher Glein led a team that developed a new approach to estimating the pH of Enceladus’ ocean using observational data of the carbonate geochemistry of plume material. This is a classic problem in geochemical studies of Earth (such as rainwater), but scientists can now solve the carbonate problem on an extraterrestrial body thanks to measurements of dissolved inorganic carbon by the Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA), and carbon dioxide gas by the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) onboard Cassini.

Glein’s team tried to create the most comprehensive chemical model to date of the ocean by accounting for compositional constraints from both INMS and CDA, such as the salinity of the plume. Their model suggests that Enceladus has a sodium, chloride and carbonate ocean with an alkaline pH of 11 or 12, close to the equivalent of ammonia or soapy water. The estimated pH is slightly higher by 1 to 2 units than an earlier estimate based on CDA data alone, but the different modeling approaches are consistent in terms of the overall chemistry of an alkaline ocean.

“It’s encouraging that there is general agreement, considering that these approaches are based on spacecraft data from a plume. This is much more difficult than getting the pH of a swimming pool, so it would not be surprising if the models are missing some of the details. Of course, we are trying to reconcile the data as much as possible because the details may provide clues to understanding the eruptive processes that turn an ocean’s chemistry into a plume,” said Glein.

A paper based on Glein’s research, “The pH of Enceladus’ ocean,” was published in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta in August. Glein is a research scientist at Southwest Research Institute, but completed the research while at the Carnegie Institution of Washington. The work was funded by the NASA Astrobiology Institute element of the Astrobiology Program at NASA.

.

A portion of the “Lost City” hydrothermal vents in the Atlantic Ocean, which may be most similar to what is happening on Enceladus. Credit: NASA

.

Hydrothermal activity for life

It is believed that Enceladus’ alkaline chemistry comes from a geochemical process called serpentinization. This happens when a rock that is rich in magnesium and iron is converted to clay-type minerals. On Earth, we see this process in very limited locations, such as the low-temperature hydrothermal vent field named Lost City in the Atlantic Ocean.

“It’s exactly what we would expect if there is a liquid water ocean in contact with rocks on and below the ocean floor on Enceladus,” Glein said.

In addition to a high pH, this process produces hydrogen gas, a potent fuel that can drive the formation of organic molecules that in some cases can be building blocks of life.

An unresolved question, however, is whether serpentinization is taking place now. If the activity is ongoing, this would provide habitable conditions, which could support an ecosystem similar to Lost City. If it occurred long ago, the high pH may be a relict and life may be less likely, although still not impossible if there are other sources of chemical energy.

Cassini did a final flyby of Enceladus in late October that targeted the chemistry of the plumes directly. The INMS team, which includes Glein, is searching for molecular hydrogen in that plume, which would be chemical evidence of active serpentinization. An absence of molecular hydrogen would be a sign that the serpentinization is extinct.

The data analysis from this flyby may be completed in time for the American Geophysical Union’s fall meeting in December. Glein added that the planned NASA mission to Europa includes advanced descendants of both the CDA and INMS instruments, meaning that in a decade or two, scientists can start to make these same measurements at Europa. This will allow us to better understand the importance of serpentinization across the Solar System.

“On other icy worlds, if they have liquid water oceans, [serpentinization] should be inevitable because these bodies are massive mixtures of water and rock,” he said. “Maybe the methane we see in Titan’s atmosphere formed when hydrogen from serpentinization combined with deep carbon in a hydrothermal environment. There may also be liquid water on [dwarf planet] Pluto, through cryovolcanoes and a youthful surface. We expect there to be some degree of water-rock interaction on such ocean worlds, setting the stage for serpentinization and the generation of hydrogen that could be utilized if there is anyone out there.”

Quelle: ASTROBIOLOGY MAGAZINE

4251 Views