.

NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft is still searching for other Earths and studying the cosmos, despite being sidelined by a mechanical problem several years ago.

After being crippled by a mechanical malfunction, NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft is back in action and has found a slew of planets orbiting other stars.

Called K2, the revamped mission has already found more than 100 confirmed planets, the University of Arizona’s Ian Crossfield announced Tuesday at a conference of the American Astronomical Society. Some of these are very different from what the spacecraft observed during its original mission; many are in multi-planet systems and orbit stars that are brighter and hotter than the stars in the original Kepler field.

It has found a system with three planets that are bigger than Earth, spotted a planet in the Hyades star cluster—the nearest open star cluster to Earth—and discovered a planet being ripped apart as it orbits a white dwarf star.

Scientists have also found 234 possible planets that are awaiting confirmation, said Andrew Vanderburg of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

“It’s probing different types of planets [than the original Kepler mission],” says Tom Barclay of NASA’s Ames Research Center. “We’re focusing on stars that are much brighter, stars that are nearer by, stars that are more easy to understand and observe from the Earth. The idea here is to find the best systems, the most interesting systems.”

.

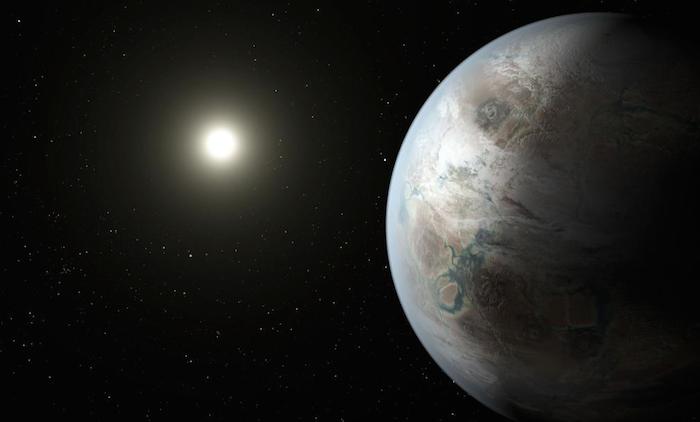

Among the planets discovered by a revived Kepler spacecraft is one in the Hyades star cluster, the nearest of its kind to Earth.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA, ESA, AND STSCI

-

From 2009 to 2013, Kepler stared at the same patch of star-filled sky, watching for periodic blips in starlight caused by orbiting planets. The mission’s goal was to determine how common Earth-like planets are, and over four years Kepler discovered more than 1,000 new planets.

But in 2013, Kepler lost its ability to stare at the same exact spot. After a tweak to its steering ability, the spacecraft can still peer into the cosmos and study alien worlds, even if it can no longer dare the universe to blink first.

But K2 isn’t looking only at planets orbiting other stars. Among other objects, it’s also spying on supernovas, and studying planets orbiting our star. In 2014, it spent about 70 days observing Neptune, studying the ice giant’s extremely windy weather.

“This is the best view, the longest view of Neptune we’ve ever had—this thing we’ve known about for hundreds of years,” Barclay says. Now, Kepler is staring at Uranus, a world that is much more placid than its blue, wind-whipped sibling Neptune, and will target a population of asteroids that share an orbit with Jupiter.

“The area I get most excited about is the study of bodies in our own solar system. It’s just so new for us, it’s something we’ve never done before with the spacecraft,” Barclay says.

“Suddenly we can look at things we can see from our backyard.”

K2 will also attempt to spot planets that are wandering through the galaxy without stars of their own. The gravity of these free-floating planets can briefly magnify the light from distant stars and galaxies, producing a fleeting increase in an object’s brightness. As Kepler stares at the sky, it will look for those brief blips that signify wandering worlds.

“For free-floating planet candidates, these timescales could be as short as days or even hours,” says Calen Henderson of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Quelle: National Geographic Society

4614 Views