.

26.08.2015

LAUREL, MD. — NASA began an early feasibility study for missions to the distant, mostly ignored ice-giants Uranus and Neptune, a senior agency official said here Aug. 24.

“I’ve asked [the Jet Propulsion Laboratory] to initiate an ice giant study,” Jim Green, NASA’s director of planetary science, said during a presentation to the agency-chartered Outer Planets Assessment Group, which met at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory here.The study will run “at least a year” once JPL, Pasadena, California, stands up what is known as a science definition team, Green said. He advised scientists here who are interested in participating on the team to watch for a formal announcement NASA will publish “soon.”

Green assigned a cost cap of $2 billion in fiscal year 2015 dollars to either orbiter mission.

The study is a long way from a NASA commitment to send a probe to either Uranus or Neptune: Largely unexplored bodies planetary scientists have long desired to observe more closely.

No NASA mission to the ice-giants would launch until the late 2020s or 2030s; the JPL-led study is intended to inform the planetary science community as it prepares to write its next 10-year science roadmap, or decadal survey, that will be published by the National Research Council around 2022, Green said.

Green said the JPL team will answer very preliminary questions: A mission’s addressable science objectives; required technology development; and whether the objectives are realistic given NASA’s budget outlook and short supply of nuclear power systems. Green said a nuclear power source would be needed for any Uranus or Neptune mission.

Before NASA mounts a mission to either planet, Uranus and Neptune will again have to receive the planetary science community’s endorsement as top destinations in the 2022 decadal.

“I’m sure they will,” Green said. “They’re very worthy.”

NASA’s Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft ever to get anywhere near Uranus and Neptune. The spacecraft snapped closeups of Uranus in 1986, and of Neptune in 1989.

Quelle: NASA

-

Update: 27.08.2015

.

Back to the Ice Giants: Proposed New Mission Would Re-Visit Uranus or Neptune (or Both!)

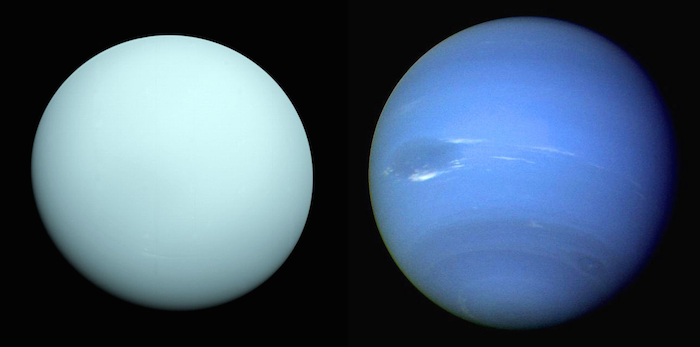

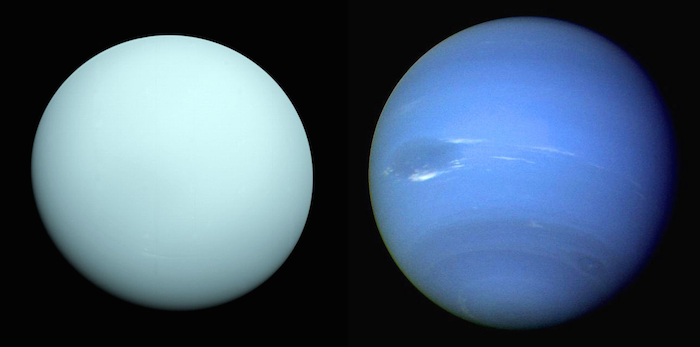

Uranus (left) and Neptune (right). These two ice giants and their many moons are awaiting further exploration. Image Credit: NASA

-

The outer Solar System has been a busy place lately, with the ongoing Cassini mission at Saturn and New Horizons’ recent spectacular flyby of Pluto. Literally in-between those two worlds, however, it has been quiet for a long time now – the last time the ice giants Uranus and Neptune were visited was 26 years ago yesterday, when the Voyager 2 spacecraft flew past Neptune. There have been no new missions to these worlds since then, but if a new proposed mission gets the green light, that may change in the not-too-distant future.

Jim Green, head of NASA’s planetary sciences, announced that NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) will now be studying a possible flagship mission to return to Uranus and/or Neptune. The news was announced at the Outer Planets Assessment Group meeting in Laurel, Maryland.

.

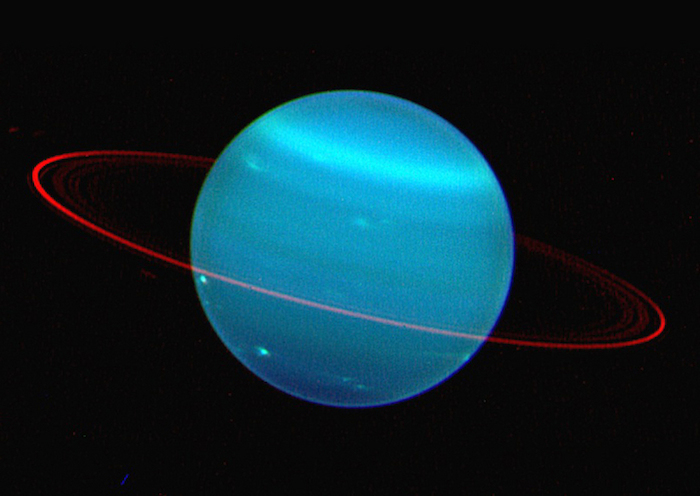

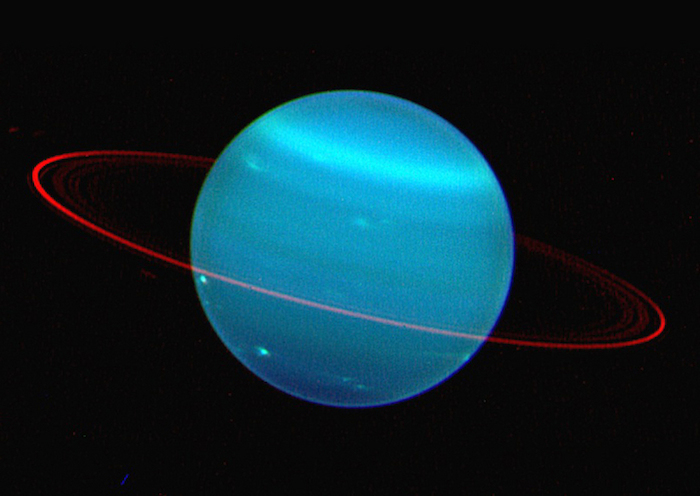

The rings of Uranus. Like Saturn, Uranus and Neptune (as well as Jupiter) are known to have ring systems, but they are much fainter and less prominent. Image Credit: Lawrence Sromovsky (Univ. Wisconsin-Madison)/Keck Observatory

“I’ve asked [the Jet Propulsion Laboratory] to initiate an ice giant study,” Green said.

NASA’s director of planetary science, – See more at: http://spacenews.com/nasa-to-study-uranus-neptune-missions/#sthash.WGnyVnWb.dpufIf it goes forward, this would be the next major Solar System mission since the Mars 2020 Rover and the Europa Multiple Flyby Mission (formerly called Europa Clipper). There is also the Juno mission currently en route to Jupiter, but it is scheduled to end by 2018. Flagship missions are larger and more complex than smaller-scale missions, designed for in-depth, ongoing study of planets and moons. Previous ones have included Cassini, Galileo and Voyager. The Cassini mission will also end in 2017, when the fuel finally runs out and the spacecraft plunges into the gas giant’s atmosphere, as planned. This new mission, if approved, should cost less than $2 billion, according to Green.

The as-yet unnamed mission could use the massive Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, now being built and tested, to get to Uranus or Neptune faster than was previously possible, although would probably still be later in the 2020s. Even, it would be unlikely to close the so-called “50-year gap,” the time between the last visit to the ice giants and the predicted return to them.

.

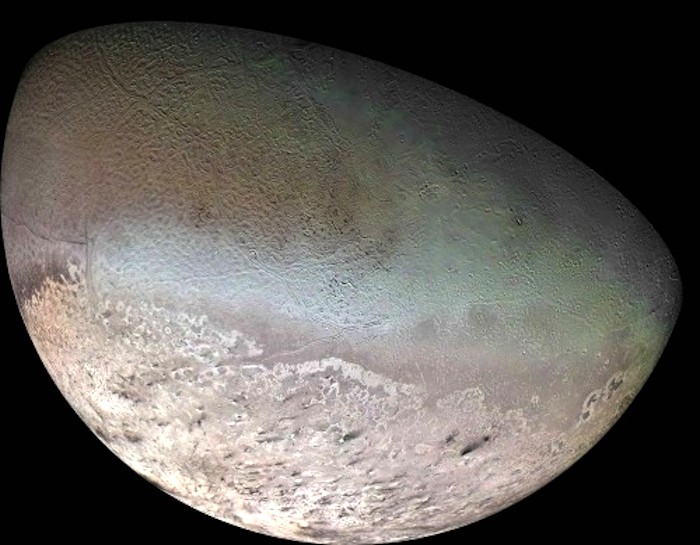

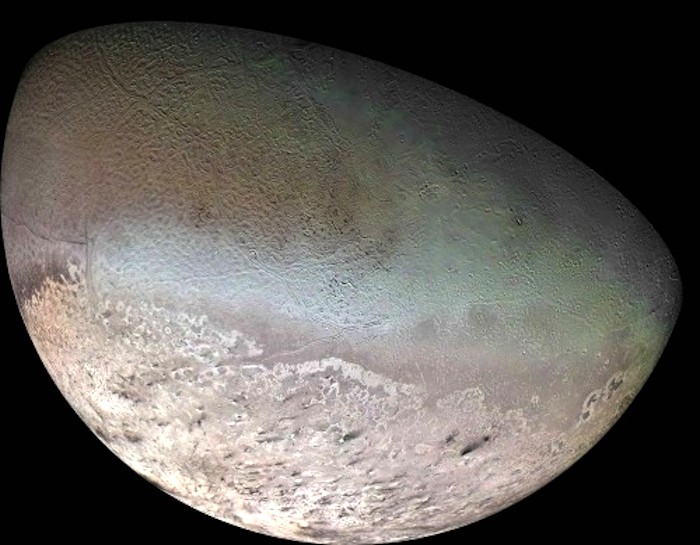

Neptune’s largest moon Triton has unusual “cantaloupe” terrain and geysers of nitrogen. Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

.

There was one previous mission proposal to return to Neptune, called Argo, but it never got off the ground due to a limited supply of plutonium, which missions to the outer Solar System use since there is not enough solar energy available at such great distances from the Sun. Argo could have launched in a timeframe of 2015 to 2020, but it is now too late for that. Argo would have required gravity assists from Jupiter and Saturn to speed up the spacecraft, but that is no longer an option at this late stage. There is now, however, funding again for plutonium, making such long journey possible again. Of course, all of this is dependant on funding, as well.

Just like the Jupiter and Saturn systems, Uranus and Neptune are of great interest to planetary scientists as they are also like miniature solar systems, with many moons of wide geological variety. They are similar in composition, with atmospheres composed primarily of hydrogen and helium, along with traces of hydrocarbons and possibly nitrogen, as well as water, methane and ammonia ices. The interiors are mostly ice and rock. Altogether, Neptune has at least 14 known moons and Uranus has 27.

Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, has active plumes or “geysers” of nitrogen erupting from ice volcanoes (cryovolcanoes). Something like the geysers on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, except those one are spewing water vapor and ice particles instead of nitrogen. So far, Triton has only been visited by one spacecraft, Voyager, and only one side was imaged in high-resolution. Even so, scientists have already seen tantalizing glimpses of this fascinating world, with weird “cantaloupe” terrain and the geysers as well as a possible subsurface ocean. The major science objectives of studying Triton closer include the interior structure, surface geology, surface composition and atmosphere, the plumes and Triton’s interaction with Neptune’s magnetosphere. Due to the scarcity of craters, Triton’s surface is thought to be quite young, only about 10-100 million years, meaning that the moon is still geologically active. Triton is also thought to possible be a dwarf planet captured by Neptune’s gravity, rather than forming in place, due to its unusual retrograde orbit.

.

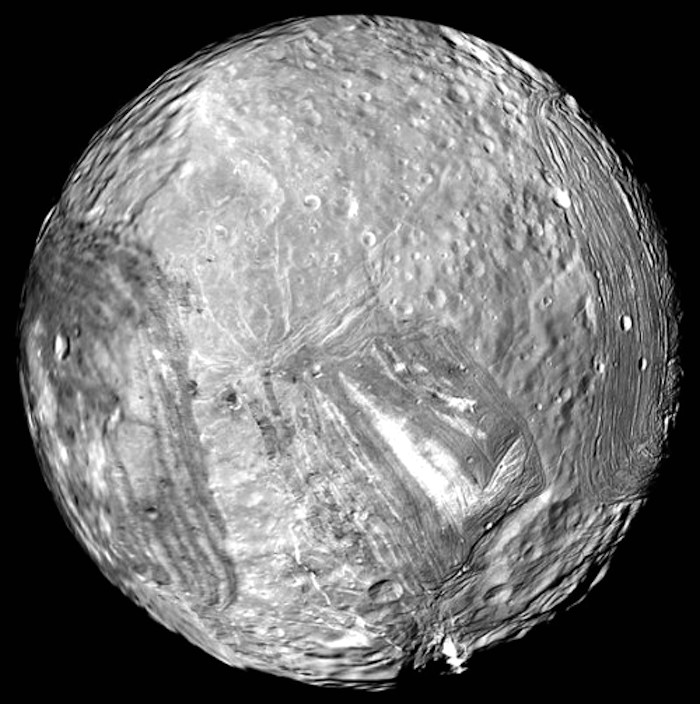

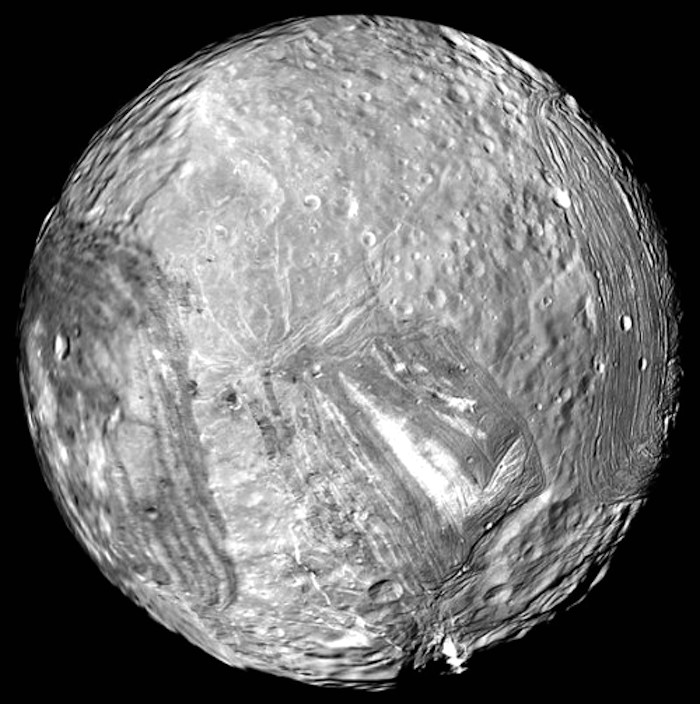

Uranus’ moon Miranda shows signs of past geological activity, with deep canyons and other chaotic terrain. Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

.

The five main moons of Uranus are Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon. They’re combined mass would be less than half that of Triton. The largest, Titania, has a radius less than half that of our own Moon. They don’t appear to be geologically active now, but Miranda has obvious signs of past activity, with deep canyons, terraced layers and a chaotic variation in surface ages and features. It looks like bits of different moons all randomly mashed together. The moon also has the tallest known cliff in the Solar System, Verona Rupes, which is 3-6 miles (5-10 kilometers) in height.

There is an extensive overview of the scientific goals of OPAG, including the continued study of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and geologically active moons such as Europa, Enceladus, Titan, Io, Ganymede and Triton. Many of these moons are known or suspected to have subsurface oceans of water, making them potentially habitable and prime targets for astrobiology and the search for evidence of life elsewhere in the Solar System, even if just microscopic. Some of the primary goals include:

Study origin and evolution of our Solar System – giant planet migration, with major complementarity with exoplanets

Investigate habitability of icy worlds – to gain insight into the origin of life on earth

Understand the dynamic nature of processes in our Solar System – importance of time domain

Explore giant planet processes and properties

Use giant planets to further our understanding of other planets and extrasolar planetary systems

Determine giant planets’ influences on habitability

Before moving forward, the proposed mission will need to be endorsed by planetary scientists in the 2022 decadal.

“I’m sure they will,” Green said. “They’re very worthy.”

Uranus and Neptune are both jewels in the outer Solar System, just waiting for further exploration; if the new proposal becomes reality, we may get a chance to do just that after all. It was once thought that the outer Solar System was a relatively dead place geologically speaking, too far from the Sun for much if any activity to be going on. But as the in-depth studies of Jupiter and Saturn have shown, that is not the case at all, with a wide variety of worlds including ones with oceans under their surfaces. Very likely, and has been hinted at so far, the same can be said about the Uranus and Neptune systems as well.

Quelle: AS

4683 Views