.

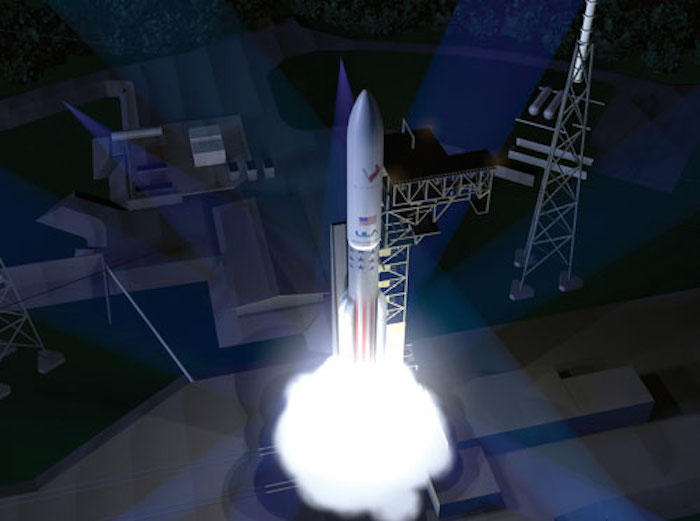

Concept art for ULA's Vulcan launch system

.

The words “affordable” and “national security space” systems are not often paired together.

The Air Force and other agencies involved in building, launching and operating satellites are better known for cost overruns.

Air Force, National Reconnaissance and Navy satellite programs were for decades plagued by delays that ultimately cost taxpayers billions of dollars. Sending the largest spacecraft to orbit was handed over to a monopoly in 2005 resulting in spiraling launch fees. And often lost in this equation was the inefficient and high price of the ground systems that carry out day-to-day satellite operations.

“Space acquisition isn’t broken and we can achieve affordability,” Lt. Gen. Ellen Pawlikowski, military deputy at the office of the assistant secretary of the Air Force for acquisition, said at the recent Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

There are movements in all three industry sectors — satellite acquisition, ground systems and launch — that have the potential to make space more affordable.

Pawlikowski, the former commander of the space and missile center, asserted that the Air Force had turned around its beleaguered satellite development enterprise.

“Everybody talks about the horror stories,” she said. “We need to stop beating ourselves up over space acquisition.”

All of the Air Force’s highest profile spacecraft acquisitions were at one time delayed by years and suffered from cost overruns. Advanced EHF and Wideband Global System communication satellites ended up being lofted years after their original dates, and hundreds of millions over budget. The space-based infrared system suffered a similar fate, as did GPS II, she noted.

“We figured out how to make those systems affordable,” Pawlikowsi said. The Air Force space procurement budget has been reduced from $11 billion to $6.7 billion since the Budget Control Act of 2012 took effect, and the service continues to successfully acquire new blocks of these spacecraft, she said, ascribing some of the success to the Better Buying Power initiatives promulgated by the Defense Department’s Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Frank Kendall.

One change was going from cost-plus to fixed price contracts. That took care of the age-old problem of requirements creep — adding features to a program while it is under development. That has always been tempting for spacecraft developers since the satellites, once lofted, can last 10 to 15 years, and acquisition personnel wanted to ensure they had the most up-to-date technology aboard.

“It disciplines the government because when you have a fixed-price contract you can’t change things around as easily because you understand the costs associated with doing that,” Pawlikowski said.

The center had to learn to understand and refine requirements and the risks associated with them, she added. As an example, the space fence — a ground-based radar system designed to track spacecraft and orbital debris — was originally budgeted as a $6 billion program, but is now $1 billion, she noted.

A recent Government Accountability Office report on space acquisitions delivered to the Senate Armed Services Committee after Pawlikowski’s speech — “Some Programs Have Overcome Past Problems, but Challenges and Uncertainty Remain for the Future” — acknowledged that some of the space and missile center’s acquisition efforts had turned around.

Cristina T. Chaplain, director of GAO acquisition and sourcing management, said most of Air Force Space Command’s programs are mature. The command is working its way through a series of analysis of alternative reports that may radically change space architecture, and it is not committed to many new development programs.

Meanwhile, one of its few new programs, GPS III, has been delayed by 28 months because of problems with its navigation payload, GAO said. Its GPS next-generation operational control system is experiencing “significant schedule delays and cost growth.” Software and cyber security upgrades may push its delivery back by four years.

Pawlinkowsi said: “We can draw our best lessons on things we have done in the last five or 10 years.” Nevertheless, she described the Air Force space acquisition enterprise as a “recovering alcoholic.” It had at one time plenty of funding, but those days are over. Fiscally, the command is in for some tough times, she said. Meanwhile, demand for space services continues to grow. ”We can’t rest on our laurels,” she added.

Lt. Gen. Samuel Greaves, Air Force space and missile center commander, said Pawlinkowski had reviewed 33 past and current programs to determine the reason for the delays.

“We intend to assure that we don’t make the same mistake twice,” he said.

The center will bring back developmental planning in a disciplined away, he said. It will retire the risks of developmental technology before building new spacecraft around it. He has instituted more frequent contractor and program feedback, not just during periodic reviews. “This will be a tough thing to do,” he acknowledged.

The center has established an advanced development directorate, which is a center of excellence for new technologies to be inserted before a program reaches milestone A decisions.

“We have to reduce risks through demonstrations and pathfinders and rigorously analyze alternatives,” he said.

Often ignored, but vitally important for reducing costs, are ground systems.

Sequestration began a drive to create common architectures and applications that may end up making ground systems more affordable, said Bob Canty, vice president of business development for Raytheon intelligence and Earth observation.

Satellite control systems were developed in stovepipes. Each fleet has its own operators, software and hardware. There is little automation, so ground stations must be manned around the clock, he told reporters.

.

SpaceX's GPS III satellite

.

Air Force Space Command Commander Gen. John Hyten said he wants a common ground system that can operate any satellite.

“We have spent tens and hundreds of millions of dollars on stand-alone ground systems … If we keep on going on this path, we’ll have five separate ground systems to operate five separate satellites. It’s the dumbest thing in the world,” he said in a speech at the symposium.

“We have to get to common ground system … and we’re going to get to it one way or another. We cannot fail in this endeavor,” he said.

Canty said before the budget crunch, the desire on the part of Space Command was to simply share data. Now, with a push for affordability, those two goals are dovetailing.

“You’re starting to see both of these things working together. As you get more common, the sharing is easier and you start getting into different ways of looking at how I can leverage the enterprise and leverage the data itself,” Canty said.

Greaves said: “Ground systems are becoming more capable of handing more complexity in terms of constellation management, infusing more types of data, delivering combat relevant information.”

Vincent Sica, vice president of ground solutions at Lockheed Martin, said it is necessary to separate the information technology backbone layer and the applications layer.

Ground station applications “were so interwoven with IT operating systems and services, that anytime you made any change you had to change the entire ground system from the IT layers to services and applications.”

A new modular separation — or what he called an “enterprise service bus” — has been slowly evolving over the past few years, allowing for more commercial-off-the-shelf products and services, he said. “We’ve had some applications where we have shown significant savings by going to a private cloud infrastructure,” he said.

There are also big savings to be had in software testing, which can account for 50 percent of any upgrade. The modularity allows for more application plug-ins, which cuts down the need for tests.

It has been a slow process because these are systems being used 24/7 to control vital satellites. He likened it to changing wheels on a car while still driving.

“You have to do it in a systematic way. Nobody has big budgets out there for big bang transitions,” he said. The transition is being made as software coding is being updated. “When you do have a new start, you obviously want to build it that way from the beginning and you can certainly see the benefits of that. In many cases you don’t see that scenario.”

The Air Force is also looking for efficiencies on the ground with its new consolidated Air Force satellite control network modifications, maintenance and operations (CAMMO) program. The service currently has different contracts to cover development, sustainment and operations of the ground control systems. CAMMO will bring all these functions under one contract and team.

That will give the Air Force an efficient trouble shooting process with one team responding to restore service, Sica said.

“I believe you should see significant savings that could be put into modifications and future upgrades,” he added.

Canty said: “Once I get these systems common, now I can operate these globally with one overall sustainment type of model.” The Air Force and other services will move toward managed services, he predicted.

Raytheon has already seen a 50 percent reduction in computing infrastructure, floor space, power and sustainment costs at ground control facilities, he added.

Common ground “transforms the way you look at your operations with better insight into data for analytics, improved agility and response time and enable smart network sensors,” Canty said.

Meanwhile, the private sector is poised to come in and offer more managed services in order to help reduce the cost of space.

The Air Force in October awarded commercial satellite communications provider Intelsat General a study contract to investigate whether such companies could take over the day-to-day tracking, telemetry and control of the Wideband Global Satcom satellites.

“Intelsat, with global operations that span over 400 antennas and that achieve 99.99 percent availability, has demonstrated that we can provide our customers with more cost efficient operations without sacrificing innovation, resiliency, quality or security,” Intelsat president Kay Sears said in a statement.

WGS spacecraft technology is based on commercial satellite systems, so a commercial satellite operator should be familiar with its operations. The comsat sector’s ground control costs are one-fifth of the U.S. military’s, the statement noted.

Rebecca Cowen-Hirsch, senior vice president, government strategy and policy at Inmarsat Inc., a comsat provider, said her company is offering an end-to-end communication system that include terminals that connect the war fighters to satellites.

It provides terminals, the satcom, a service level agreement and technology refresh.

“They hold us accountable to a service level agreement and a committed information rate,” she said. This may be particularly attractive because military customers often put off refurbishing or replacing their radios and terminals for budget reasons, she said.

This is another element the government can put in its portfolio to consider its investment strategies, she said. Inmarsat already has one “small scale” U.S. government customer for this managed service, although she declined to disclose its identity.

Without assured access to space, national security satellites cannot make it to orbit. The government long ago stopped acquiring its own rockets and instead asked contractors to provide launch services. Only two companies at the time were able to manufacture rockets powerful enough to loft the heaviest satellites: Lockheed Martin and Boeing.

They formed United Launch Alliance in 2005 and the joint venture has had a monopoly on heavy lift since then. Launch fees rose dramatically over the past decade, although GAO’s Chaplain said that those costs are now under control.

.

SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk, is expected to have its first rocket certified for national security launches this summer, and is beginning the process of having its Falcon 9 Heavy certified.

Meanwhile, ULA announced that it will scrap the Atlas 5 and Delta 4 rockets it currently employs and develop a new launch system it calls the Vulcan. It is aiming to send the first rocket to orbit in 2019.

The space launch industry is fundamentally different — and much healthier — than it was in the past, Hyten said. “That’s the good news. But it is a very complicated industry.”

Ultimately, the Air Force must have at least two competitors to guarantee assured access to space, Hyten told reporters in Washington, D.C. The Air Force wants more competition to bring costs down. But questions remain: “If I’m buying launch as a service, how do I then make sure I still have access to space in this commercial partnership?” Hyten asked.

“If one provider is 5 percent cheaper than the other, and both are equally effective, you still have to keep the second operator in business,” he said. There will have to be launches carved out for the second provider to meet the national policy objectives. “That’s a very complicated business arrangement that we’re going to have to work out with our partners.”

Chaplain acknowledged that space is a difficult field. “We recognize DoD has made strides in recent years in enhancing its management and oversight of space acquisitions and that sustaining our superiority in space is inherently challenging, both from a technical perspective and a management perspective.”

Quelle: NDIA

5062 Views