.

7.04.2015

BEPICOLOMBO ANTENNA IN LSS

RADIO TESTING OF BEPICOLOMBO ORBITER

MEET THE FLEET

BepiColombo: Joint Mercury mission ready for 'pizza oven'

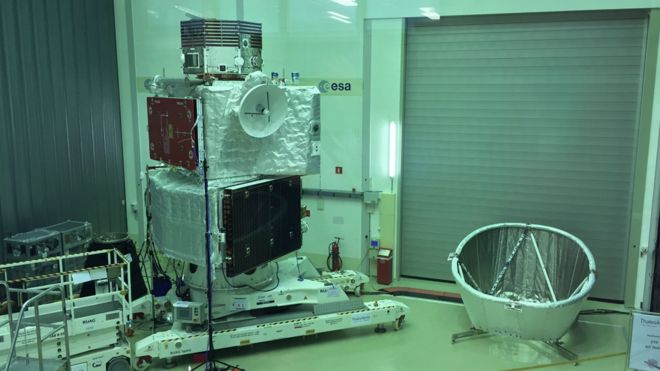

The two satellites that make up the BepiColombo mission to Mercury were presented to the media on Thursday.

This joint European-Japanese venture has been in development for nearly two decades, but should finally get to the launch pad in 15 months' time.

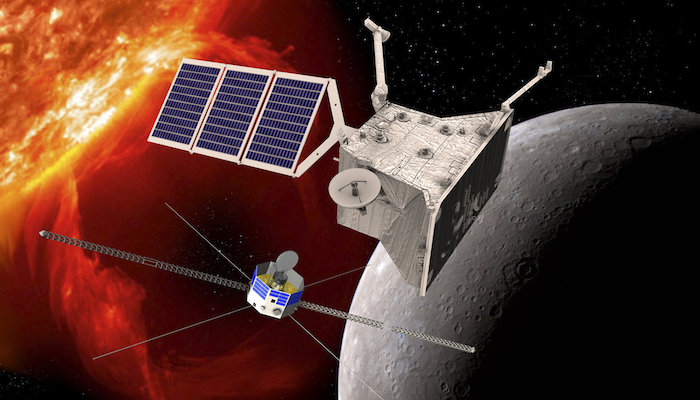

The two spacecraft will travel together to the baking world but separate on arrival to conduct their own studies.

Thursday's event in the Netherlands was the last chance for journalists to view the so-called "flight stack".

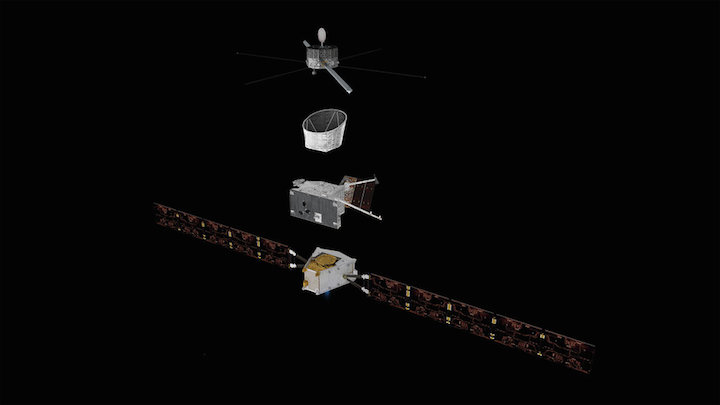

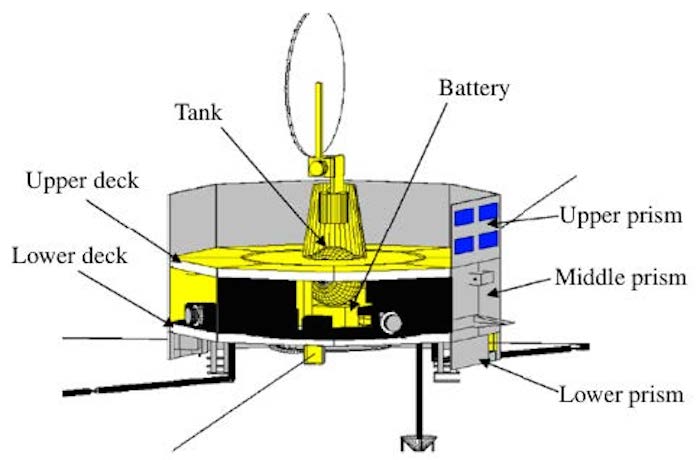

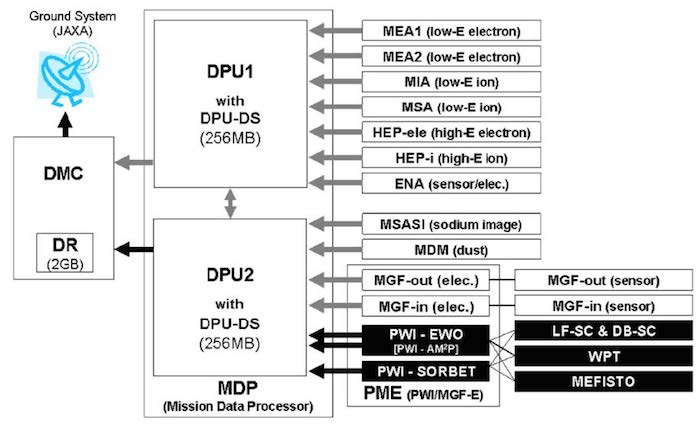

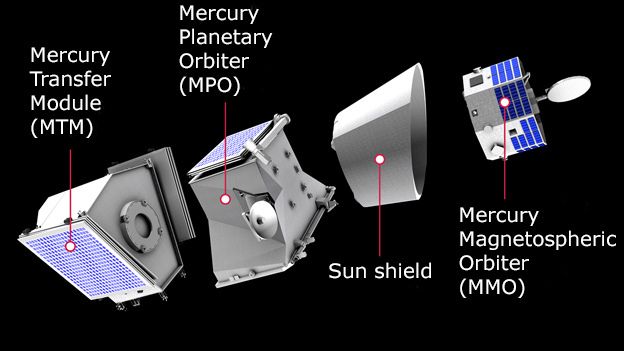

This is the edifice that goes on top of the rocket and comprises Europe's Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and Japan's Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO), as well as the propulsion module to control their path towards the world that circles closest to the Sun.

As a single item, the stack has just finished a series of important tests, but it will shortly be taken apart so that the individual components can continue with their own preparations. The structure will not be reassembled until all equipment reaches the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana.

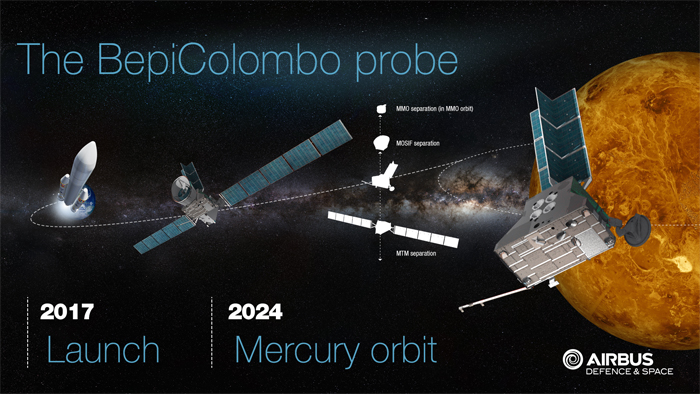

The double mission is due to blast away from Earth on an Ariane rocket in October 2018. Everyone will have to be patient, however. It is going to take seven years for the satellite duo to get to their destination.

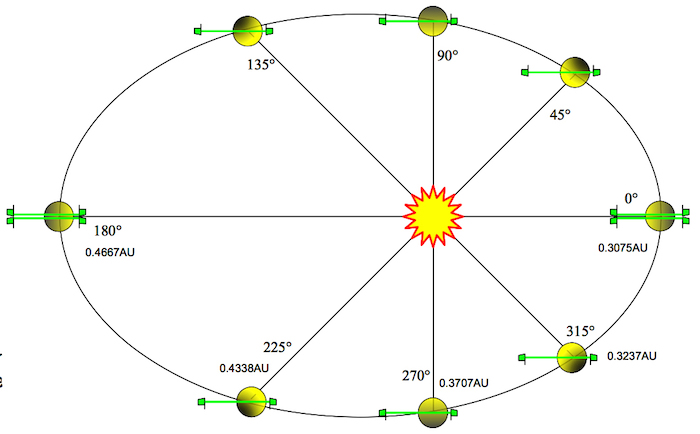

The gravity of the Sun pulls hard on any spacecraft travelling into the inner Solar System, and Bepi will have to fire thrusters in the direction of travel to ensure it does not overshoot Mercury.

"Mercury is the least explored of the rocky planets, but not because it is uninteresting," said Prof Alvaro Giménez Cañete, the director of science at the European Space Agency (Esa).

"It's because it's difficult. It's difficult to get there; it's even more difficult to work there."

Temperatures on the surface of the diminutive world go well above 400C - hot enough to melt some metals, such as tin, zinc and lead.

- Europe's Mercury mission takes shape

- Mercury mission ends with a bang

- Water bonanza at Mercury's pole

How to build a mission to Mercury

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA

- MTM is a propulsion module to control the cruise to Mercury

- Europe's Mercury Planetary Orbiter carries 11 instruments

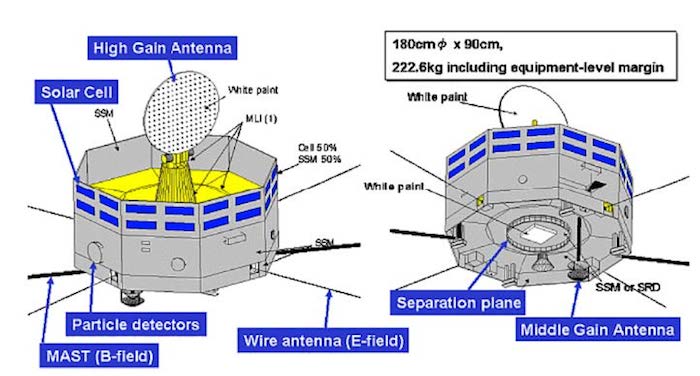

- For the cruise phase, a sun shield protects the MMO

- At Mercury, Japan's orbiter dispenses with the shield

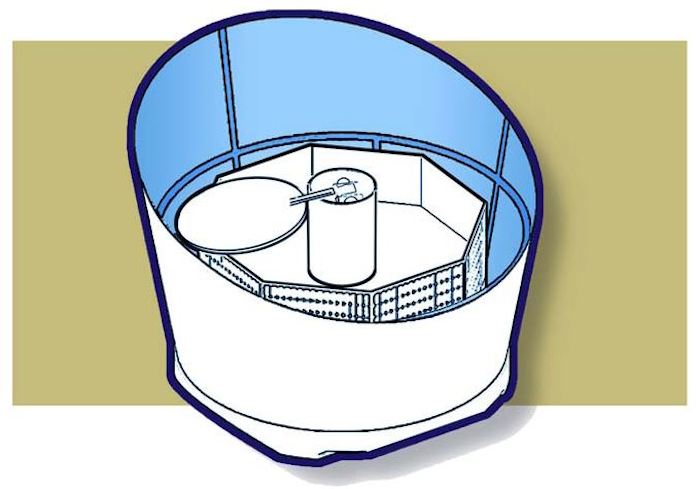

- It will simply spin to prevent its surfaces from overheating

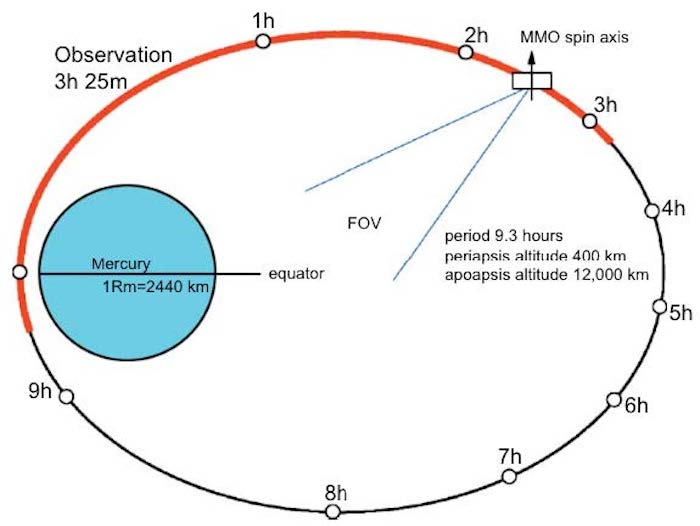

- MMO and MPO will go into different polar orbits at Mercury

The MPO and MMO will be looking to deepen and extend the knowledge gained at Mercury by the US space agency’s recent Messenger mission.

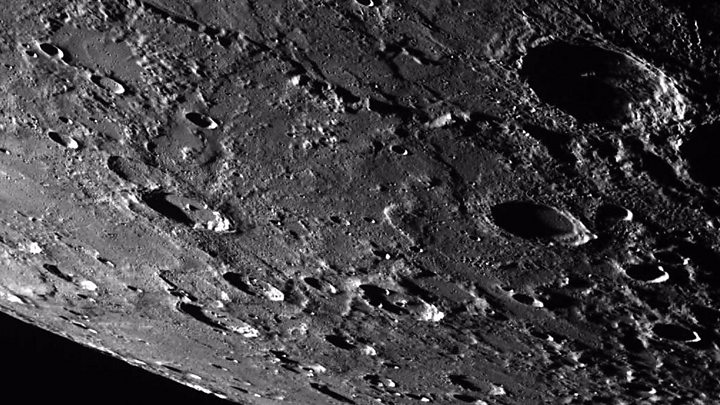

The American probe, which ceased operations in 2015, took some 270,000 images of the planet's surface and acquired 10 terabytes of other scientific measurements.

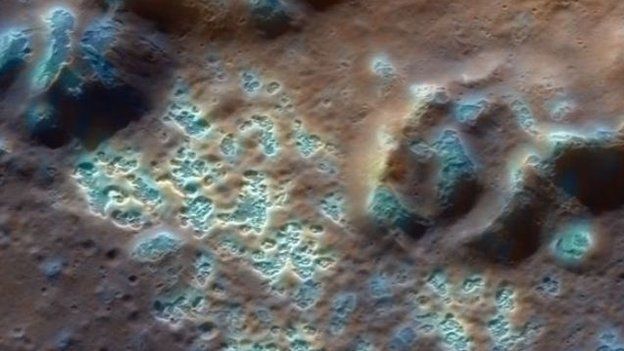

It provided remarkable new insights on the composition and structure of the smallest terrestrial planet, and it made the amazing discovery that, despite those high temperatures, there are shadowed craters where it is still cold enough to support water-ice.

Esa and the Japanese space agency (Jaxa) hope that the more advanced, higher-resolution technology on their satellites will be able to answer questions that Messenger could not.

Esa's BepiColombo project scientist, Johannes Benkhoff, said: "We need to come up with new ideas. And for that reason we need to have good instrumentation and we need to do very close monitoring of the planet; and we can do that with our spacecraft that we're sending to Mercury."

The oddball close to the Sun

- Past Mercury visitors were Nasa missions: Mariner 10 and Messenger

- The planet's diameter is 4,880km - about one-third that of the Earth

- It is the second densest planet in the Solar System: 5.4 grams/cu cm

- The Caloris Basin is the largest surface feature (1,550km across)

- It is an extreme place: surface temps swing between 425C and -180C

- There is water-ice in the planet's permanently shadowed craters

- Mercury's huge iron core takes up more than 60% of the planet's mass

- Apart from Earth, it is the only inner planet with a global magnetic field

The key conundrum is why the planet contains an outsized iron core and only a thin veneer of silicate rocks.

A favoured theory before Messenger was that Mercury at some point in its history was stripped of its outer layers, either by a big collision with another body or by the erosive effects of being so close to the Sun.

But the American probe observed large abundances of volatile substances. "They shouldn't be there had those events happened in Mercury's past; the sulphur and potassium volatiles on the surface just shouldn't be there," insisted Prof Emma Bunce, a principal investigating scientist from Leicester University, UK.

"And the other mystery about the surface is that there isn't much iron on it, seemingly; and so that needs to be looked into in more detail and that's something we'll be able to do with our imaging X-ray spectrometer, MIXS."

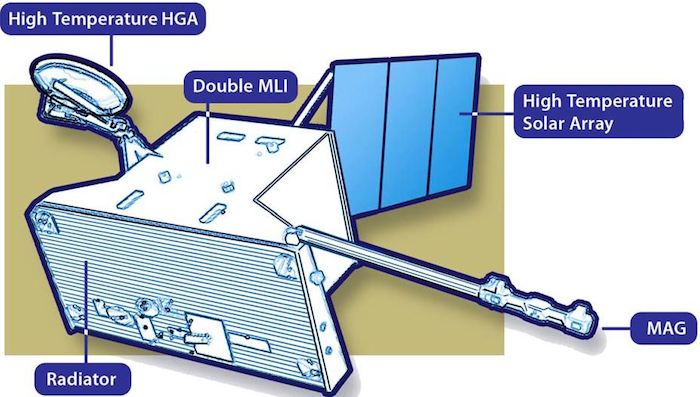

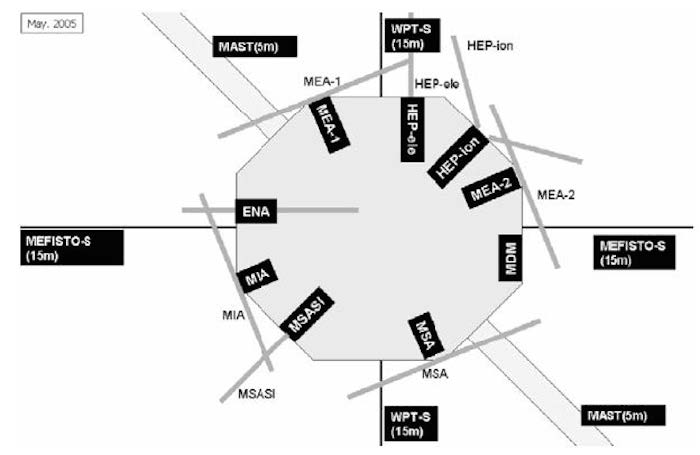

Europe's MPO will have a total of 11 instruments onboard. It will fly in a near-circular polar orbit around the planet, mapping the terrain, generating height profiles, sensing the interior, and collecting data on surface composition and the wispy "atmosphere".

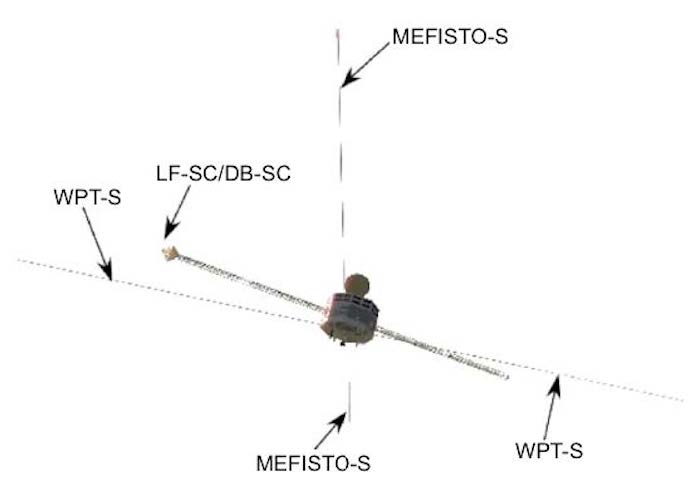

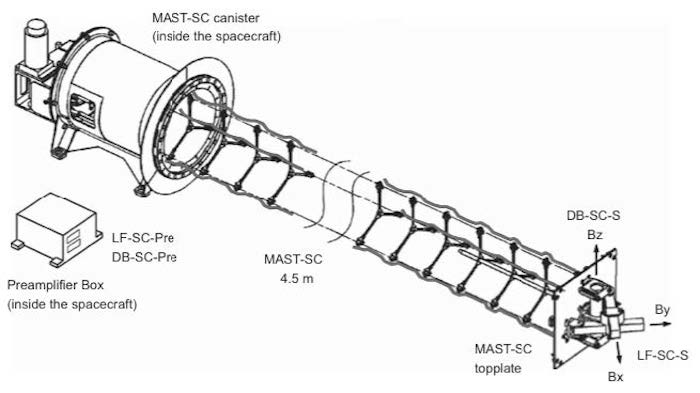

Japan's MMO will have five instruments and will investigate the planet's magnetic field.

Mercury is the only terrestrial planet - apart from Earth - to have a global magnetic field. But it is an odd one. The field is roughly three times stronger in the northern hemisphere than it is in the south.

Both Esa and Jaxa are delighted to at last be approaching launch.

The development of the mission, particularly on the European side, has been a torrid learning curve.

The launch date was repeatedly put back as engineers struggled to find equipment that could cope with the intense heat and radiation experienced just a few tens of millions of km from the Sun. The development of solar cells in particular proved extremely problematic.

"We're flying into a pizza oven," quipped Esa project manager Ulrich Reininghaus. "We had to test materials at different, very high temperature regimes, sometimes with very unwanted results."

When Esa's Science Programme Committee originally green-lit BepiColombo in 2000, it had in mind a launch in 2009. Even when the industrial contract to build the MPO was finally signed in 2008, a launch was thought possible in 2013.

Esa says the mission is costing roughly €1.65bn (£1.45bn; $1.85bn). This includes all European and Japanese costs.

One fascinating aside. That SPC meeting in 2000 also approved Esa participation in the successor space telescope to Hubble, which is called the James Webb Space Telescope. Its development schedule has also been heavily delayed and is itself now booked for launch on an Ariane in October 2018.

But it is not possible to put both missions up at the same time, so one will have to stand aside. A decision on whether it is Bepi or JWST that goes first is likely to be made this September.

Quelle: BBC

---

Update: 7.07.2017

.

PREPARING FOR MERCURY: BEPICOLOMBO STACK COMPLETES TESTING

ESA’s Mercury spacecraft has passed its final test in launch configuration, the last time it will be stacked like this before being reassembled at the launch site next year.

BepiColombo’s two orbiters, Japan’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter and ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter, will be carried together by the Mercury Transport Module. The carrier will use a combination of electric propulsion and multiple gravity-assists at Earth, Venus and Mercury to complete the 7.2 year journey to the Solar System’s mysterious innermost planet

Once at Mercury, the orbiters will separate and move into their own orbits to make complementary measurements of Mercury’s interior, surface, exosphere and magnetosphere. The information will tell us more about the origin and evolution of a planet close to its parent star, providing a better understanding of the overall evolution of our own Solar System.

To prepare for the harsh conditions close to the Sun, the spacecraft have undergone extensive testing both as separate units, and in the 6 m-high launch and cruise configuration.

One set of tests carried out earlier this year at ESA’s technical centre in the Netherlands focused on deploying the solar wings, and the mechanisms that lock each panel in place. The 7.5 m-long array of the Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the two 12 m-long array of the Mercury Transport Module will be folded while inside the Ariane 5 rocket.

Last month, the full spacecraft stack was tested inside the acoustic chamber, where the walls are fitted with powerful speakers that reproduce the noise of launch.

Just last week, tests mimicked the intense vibrations experienced by a satellite during launch. The complete stack was shaken at a range of frequencies, both in up-down and side-to-side motions.

These were the final tests to be completed with BepiColombo in mechanical launch configuration, before it is reassembled again at the launch site.

In the coming weeks the assembly will be dismantled to prepare the transfer module for its last test in the thermal–vacuum chamber. This will check it will withstand the extremes of temperatures en route to Mercury.

The final ‘qualification and acceptance review’ of the mission is foreseen for early March. Then BepiColombo will be flown to Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, in preparation for the October 2018 departure window. The date will be confirmed later this year.

“This week was the last opportunity to see the spacecraft in its stacked launch configuration before it leaves Europe. The next time will be when we are at the launch site already fueled,” says Ulrich Reininghaus, ESA’s BepiColombo Project Manager. “This is quite a milestone for the project team. We are looking forward to completing the final tests this year, and shipping to Kourou on schedule.”

Quelle: ESA