On Thursday, NASA announced that a flyby mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa, planned for the 2020s, will be called Europa Clipper and it will look for signs of habitability and life on the moon.

Right now, scientists are working with limited data, because most of the information from the Galileo probe focused on Jupiter itself. But NASA is moving forward with the mission to Europa because of the compelling possibility of finding extraterrestrial life. Europa has an icy crust, but underneath, it’s an ocean world. And water means one thing: the potential for alien life to make a home for itself.

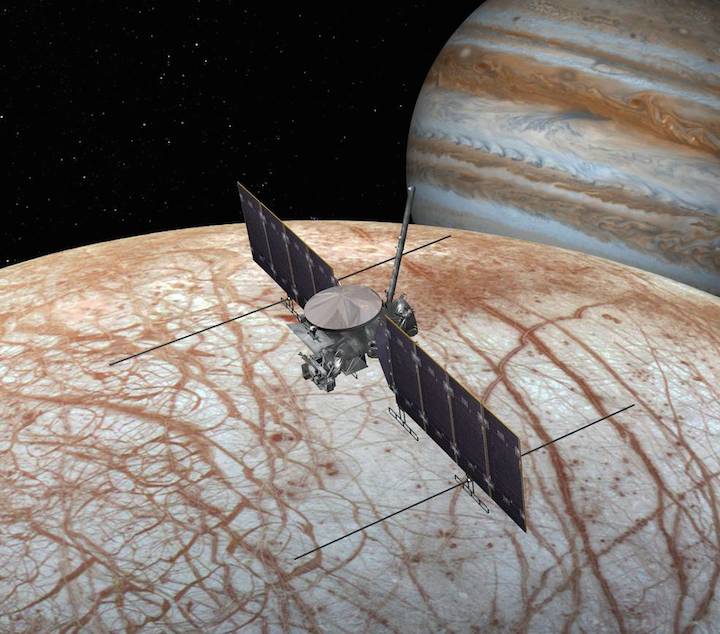

After the six-ton Clipper spacecraft is launched, it will reach Jupiter in 2.7 years. Once it reaches its destination, it will sail past Europa every two weeks and make 40 to 45 flybys.

During this time, it plans to find the best place on Europa for finding life in a future landing mission, whether it’s near plumes, fresh ice, or somewhere else. It will also take high-resolution images of the icy surface, investigate the composition and structure of Europa’s interior and shell, and test the technology needed for the lander.

Here are three things you need to know about upcoming missions to Europa.

Why do scientists suspect there might be life on Europa?

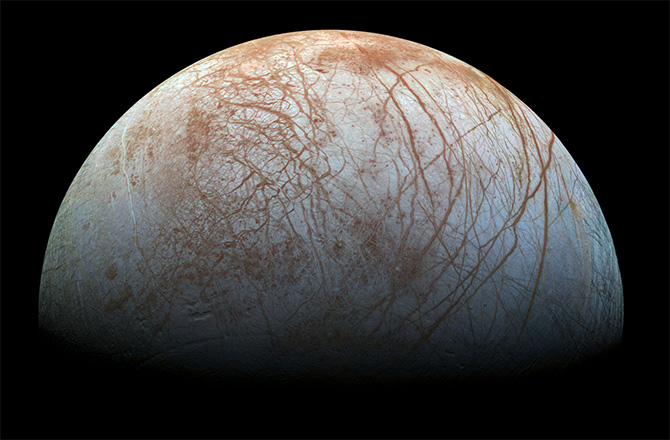

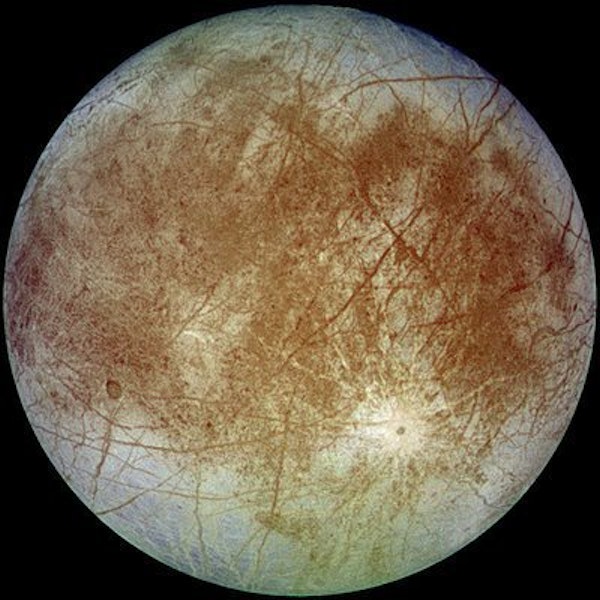

On the outside, Europa looks like a deserted planet, prone to deadly radiation from Jupiter.

But beneath the crust, there’s an ocean scientists believe is over 60 miles deep, which is exactly where the Clipper will search for signs of life. Scientists believe that Europa has twice as much water than Earth, and the radiation on the surface may actually benefit life in the oceans.

That’s because radiation from Jupiter’s magnetosphere breaks down water molecules into hydrogen and an oxygen-hydrogen molecule, and over time, those molecules combine to form hydrogen peroxide. This eventually decays into hydrogen and oxygen. And while the lighter hydrogen molecules escape into space, the heavier oxygen stays on the surface.

The age of Europa’s surface varies between 10 million and 100 million years old, which means periodically some parts of the ice shell are brought into the ocean, delivering oxygen into the water.

At the bottom of its ocean, Europa likely has hydrothermal vents or similar structures. In Earth’s oceans, life thrives in the superheated water spewing from hydrothermal vents.

With oxygen, energy, and water, Europa might just have aquatic life swimming beneath its icy shell.

What’s going to happen on the upcoming mission to Europa?

So far, the Clipper team already selected ten instruments for this mission and tested some spacecraft components.

The Clipper mission recently entered Phase B, or its preliminary design phase, where the team will continue testing components, do preliminary design, select prototype hardware elements for scientific instruments, and start building and testing spacecraft subassemblies.

In February, NASA received a report for a possible landing mission to Europa, which has been in the works since June 2016. In the landing mission, a probe will search for evidence of alien life on Europa, assess its habitability, and characterize the surface and subsurface for future explorations to this moon and its ocean.

NASA has also made progress in the problem of planetary protection, or the concern that microbes from Earth can contaminate Europa’s ecosystem. To solve this problem, before launching, a lander will bake at extremely high temperatures to kill contaminants, and when its work on Europa is done, it will self-destruct.

Clipper will cost $2.7 billion, and this doesn’t include the launch vehicle and some other vehicles. In total, it will likely cost $3 to $4 billion, and the landing mission will cost about the same. In total, these missions to Europa will cost NASA as much as $8 billion.

It’s a gamble whether we’ll find life there, but a lander has higher chances of finding life because it can test the ice.

What would a lander do on Europa?

The lander would burrow 10 cm below Europa’s surface to search for signs of life. The lander features a sampling arm with a “cutter,” or a small rotary saw. Since Europa is so cold, the ice is harder than granite, but engineers have tested 35 types of blades on 25 different surfaces to find the best tool for cutting ice. In total, the lander would collect five samples.

Besides the cutter, the lander would also bring a microscope capable of seeing cells, as well as spectrometers to corroborate evidence of life. In August, there will be a call for proposal submissions to build instruments, and they’ll be selected in May 2018.

Besides searching for life, the lander would also analyze the habitability of the oceans, such as the water’s chemistry and the ice shell’s thickness, as well as study Europa’s physical features for future expeditions.

The surface mission should last 20 days, as the batteries have a capacity of 45kWh. This is the same amount of energy as a MacBook Pro operating at full capacity for a straight month.

Quelle: INVERSE

---

Update: 1.04.2017

.

Europa lander work continues despite budget uncertainty

WASHINGTON — The NASA team studying a lander mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa says their work is continuing even though the White House is requesting no funding for the mission in its latest budget.

In a presentation at a meeting of the Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Science at the National Academies here March 29, Barry Goldstein of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory said that ongoing studies of the proposed lander are continuing, including a mission concept review scheduled for June.

“We still have enough funding to make it through the end of the year for development,” he said. “We’re going to pursue the mission concept review and let the chips fall where they may as we proceed.”

The administration’s fiscal year 2018 budget blueprint, released March 16, proposed a record-high $1.9 billion for NASA’s planetary science program, including support for the Europa Clipper mission that will go into orbit around Jupiter and make dozens of flybys of Europa.

However, the document explicitly ruled out funding for the follow-on lander mission. “To preserve the balance of NASA’s science portfolio and maintain flexibility to conduct missions that were determined to be more important by the science community, the Budget provides no funding for a multi-billion-dollar mission to land on Europa,” the document stated.

The lander mission, along with Europa Clipper, has enjoyed strong support from Congress, notably from Rep. John Culberson (R-Texas), chairman of the House appropriations subcommittee that funds NASA and an advocate of exploration of the icy moon that scientists believe is potentially habitable. Culberson, in recent years, has provided funding for Europa Clipper well above any administration request and at one point called for launching both Europa Clipper and the lander simultaneously.

Culberson did not mention the budget proposal in brief comments at the end of the public lecture about Europa exploration here March 29, but did reiterate his support for sending both orbiter and lander missions there.

He said he reached final agreement with fellow appropriators for a fiscal year 2017 spending bill that must be passed by April 28, when the continuing resolution that currently funds NASA and other federal agencies at 2016 levels expires. He didn’t provide details about the contents of that bill, which has not yet been formally introduced, but said, “You’ll be very pleased with the result.”

Goldstein, at the committee meeting, said the funding the proposed mission has received has helped make major progress on its design. “We’ve done an enormous amount of not only technical design, but also programmatic design, evaluating the capabilities and how long it will take to make this mission come to fruition,” he said.

That design, he said, permits a launch no earlier than October to December of 2025 on a Space Launch System rocket. No other launch vehicles, he said, have the performance to launch the lander mission, and even an SLS launch requires the use of an Earth gravity assist that would send the spacecraft to Jupiter, arriving in mid-2030.

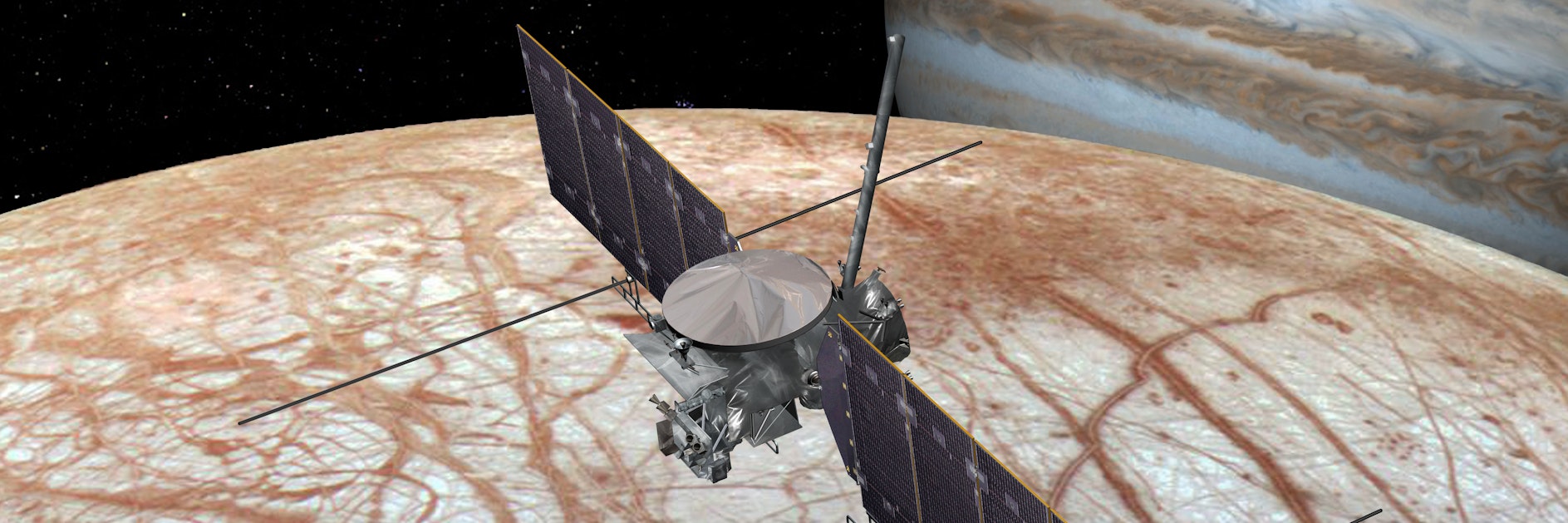

The choice of launch vehicle and trajectory is driven by the spacecraft’s mass of 16.6 metric tons. By comparison, he said, Europa Clipper weighs 6 metric tons, and will be the largest spacecraft JPL has built to date. “Almost all of that mass is either liquid of solid propellant” to place the spacecraft into orbit around Jupiter and then Europa, and for the landing itself, he said.

The lander itself will be able to accommodate a payload of 42.5 kilograms of science instruments, with a notional suite of five instruments proposed by scientists in a report released in February. Those instruments would support the goals of looking for evidence of life on Europa, assess its habitability and characterize the moon to support future missions there.

The lander will use a “skycrane” landing system similar to that employed to the Mars Curiosity lander. Goldstein said early concepts of the lander looked similar to the 1990s Mars Pathfinder spacecraft, with petals to stabilize the spacecraft.

“The team looked at that quite a bit and realized… that it was very susceptible to ‘pathological’ landing cases that would end the mission,” he said, referring to the jagged terrain seen on much of the moon’s icy surface. The lander will instead use what Goldstein described as the “cricket” design, with four landing legs in lieu of petals.

The battery-powered spacecraft is designed for a 20-day mission after landing, although that could be extended depending on how many samples the spacecraft collects and processes with its robotic arm. At the end of the mission, the spacecraft will self-destruct using a “thermite-based incinerator” to comply with planetary protection requirements. That system can also be triggered if the spacecraft loses contact with the Earth.

“Like in ‘Mission Impossible,’ we’ll hit the self-destruct button and sterilize,” he said.

Quelle: SN