.

6.01.2015

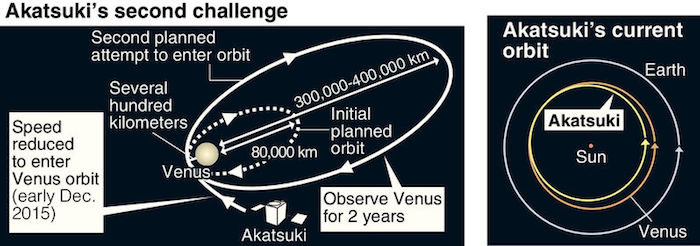

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency plans to have its probe Akatsuki reattempt an entry into the orbit of Venus in early December, probably its last chance due to low fuel, following a failed endeavor to do so in December 2010 because of engine trouble.

According to JAXA, the agency has been looking for an opportunity to have Akatsuki make a new attempt, while checking if the probe was still functional.

If the second attempt succeeds, Akatsuki will be Japan’s first probe to enter the orbit of a planet other than Earth.

According to JAXA, Akatsuki is currently located about 134 million kilometers from Venus and is shortening the distance by about 400,000 kilometers a day.

In the previous attempt, Akatsuki tried to enter Venus’ orbit by burning its main rocket in reverse to decelerate. But the rocket stopped working midway and the probe passed Venus. JAXA believes the engine likely malfunctioned due to abnormally high temperatures.

.

JAXA made gradual adjustments to Akatsuki’s course, eventually having the probe orbit the sun on the off chance Akatsuki could approach Venus once more.

The agency initially considered a second attempt at the end of 2016, but decided instead to aim for an orbit in November this year over concern that the probe’s body is deteriorating from the sun’s heat. Following calculations, the agency said the ideal orbital insertion window was in early December.

According to the plan, Akatsuki aims to enter an oval orbit several hundreds to 400,000 kilometers above the planet by reducing its speed with four of its 12 small engines to control the probe, as its main engine is out of order.

Venus is almost the same size as Earth, which is why it is called “Earth’s sister planet.” But Venus has surface temperatures of 500 C, not to mention atmospheric pressure about 90 times stronger than its “sister.” JAXA says Akatsuki is scheduled to observe Venus by revolving around the planet, taking eight to 10 days in each orbit over two years as it delves into why the planet’s conditions became so severe.

The second attempt will have fewer observation opportunities as well as degraded image quality taken by its on-board camera as the orbit is farther from Venus than initially planned. But JAXA Prof. Masato Nakamura who leads the Akatsuki project said, “Provided the equipment works, we should be able to make most of the planned observations.”

The biggest hurdle looms ahead: Akatsuki will approach the sun in February and August before orbit insertion. By then, some of the probe’s equipment will encounter temperatures as high as nearly 200 C. Nakamura added the minimum requirements for the second attempt will be met if the probe survives unscathed with no fuel leakage.

Quelle: The Japan News

-

Update: 7.02.2015

.

Venus Climate Orbiter “AKATSUKI”

Re-injection to Venus Orbit and Observation Plan

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency has decided the schedule for the Venus Climate Orbiter “AKATSUKI” to be injected into the Venus orbit in the winter of 2015, as well as its observation plan.

After failing to be inserted into the Venus orbit in December 2010, JAXA has been carefully studying another attempt opportunity for the injection when the orbiter meets Venus in the winter of 2015.

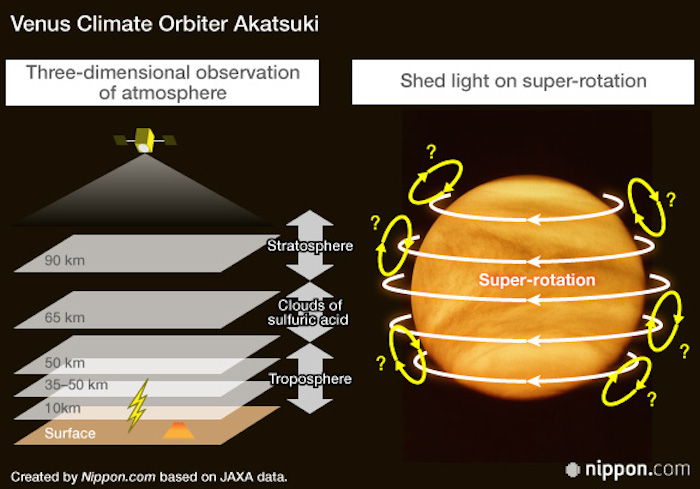

After being injected into the orbit, the AKATSUKI will observe the atmosphere of Venus, which is often referred to as a twin sister of the Earth, through remote sensing. Its observations are expected to develop “Planetary Meteorology” further by elucidating the atmospheric circulation mechanism and studying the comparison with the Earth.

1. Injection schedule to Venus orbit

Planned date: Dec. 7 (Mon.), 2015 (Japan Standard Time)

2. Observation plan

The observation plan of the AKATSUKI is to measures the following with a multiple number of wave lengths from an elliptical orbit around Venus whose period is eight to nine days.

When flying further away from Venus, or about 10 times the radius of Venus from the planet, the AKATSUKI will continuously observe Venus as a whole to understand its clouds, deep atmosphere, and surface conditions.

When flying closer to Venus, or less than 10 times the radius of Venus, the orbiter will conduct close-up observations to clarify cloud convection, the distribution of minute undulatory motions and their changes.

When the AKATSUKI comes closest to Venus, it will observe the layer structure of clouds and the atmosphere from a lateral direction.

When the orbiter is in the shade of the sun, it will monitor lightning and airglow (night glow.)

The AKATSUKI will also observe to capture the atmospheric layer structure and its changes by emitting radio waves that penetrates the atmosphere of Venus and receiving them on the ground.

Quelle: JAXA

-

Update: 20.11.2015

.

JAXA mission updates: Akatsuki Venus orbit entry!

Akatsuki is finally approaching its second attempt to enter Venus orbit, on December 7. The mission is asking its fans to share messages and tweet #あかつき応援 ("Akatsuki cheer") in their support. Even astronaut Kimiya Yui is getting into the act of cheering on Akatsuki.

It looks like the best place for updates on Akatsuki's status is the mission's Twitter feed. They have successfully tested several of the cameras, and the rest of the science instruments will be checked out after orbit insertion. They also have rehearsed the day of orbit entry, coordinating with the Japanese ground stations at Usuda and Uchinoura as well as NASA's Deep Space Network. There is a detailed post summarizing Akatsuki's status and the plans for orbit insertion at spaceflightnow.com today.

I am really not sure what to think of Akatsuki's chances for orbit entry using nothing but its steering rockets, but I am confident that the mission engineers have done everything they possibly could to increase Akatsuki's chances for success. So my wishes for the Akatsuki Venus orbit entry attempt are for the aerospace engineer's favorite word: I wish everything is nominal! Go Akatsuki!

Quelle: JAXA

-

Update: 2.12.2015

.

AKATSUKI: Second attempt to enter Venus orbit

The Venus Climate Orbiter AKATSUKI will try to enter the orbit of Venus on Dec. 7 (Mon.) after five years of operation. We are welcoming support messages.

After AKATSUKI’s failure to enter Venus' orbit on Dec. 7, 2010, JAXA investigated the cause and considered a second attempt schedule while operating the satellite for a long period. Now, on Dec. 7, 2015, coincidentally the same day on the calendar as the previous attempt, we will perform the injection for the second time.

The AKATSUKI is in a good condition and it will take a few days of confirmation to know the result. Your support for the AKATSUKI and its project team members is very much appreciated.

Quelle: JAXA

-

Update: 7.12.2015

.

Venus Climate Orbiter “AKATSUKI”

Result of Attitude Control Engine Thrust Operation

for Venus Orbit Insertion (VOI-R1)

December 7, 2015 (JST)

National Research and Development Agency

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)

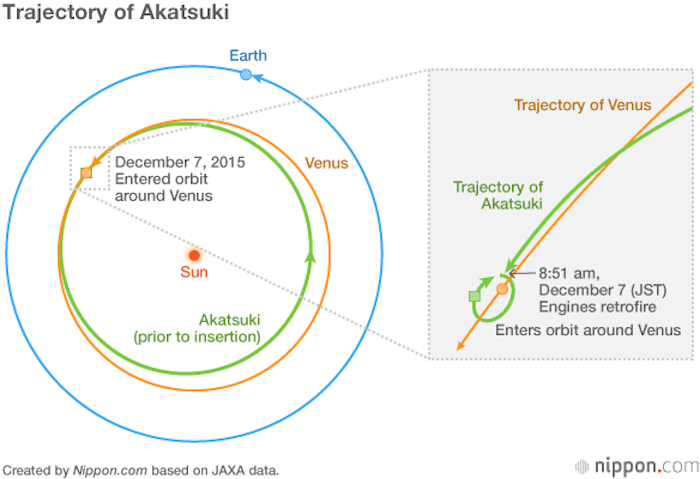

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) performed the attitude control engine thrust operation of the Venus Climate Orbiter “AKATSUKI” for its Venus orbit insertion from 8:51 a.m. on December 7 (Japan Standard Time).

As a result of analyzing data transmitted from the orbiter, we confirmed that the thrust emission of the attitude control engine was conducted for about 20 minutes as scheduled.

The orbiter is now in good health. We are currently measuring and calculating its orbit after the operation. It will take a few days to estimate the orbit, thus we will announce the operation result once it is determined.

Quelle: JAXA

---

Update: 21.00 MEZ

.

AKATSUKI's first shots of Venus taken during health check

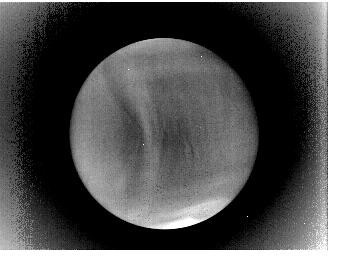

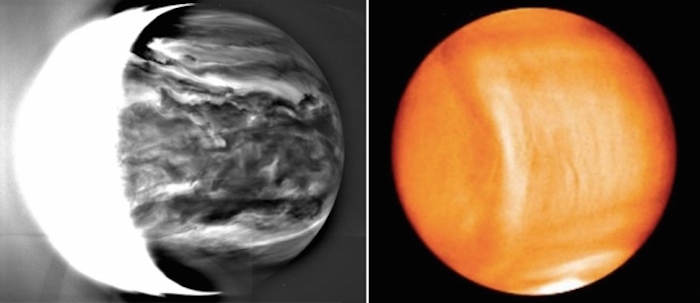

Given the failure of injecting AKATSUKI into the planned Venus orbit, the project team and a dedicated investigation team led by the ISAS Director are now conducting extensive analyses of its cause. Various functionality and health checks of the probe are now underway. As a result of this activity, we obtained images of Venus at around 9 a.m. on Dec 9th (JST).

The project team switched on the long wave infrared camera (LIR), ultraviolet imager (UVI), and 1 micron camera (IR1) to take images of Venus at the distance of 0.6 milion km*. Venus was pictured with the angular size of about 1.2 deg**.

* Distance between Earth and the moon is 0.38 milion km

** Angular size of the moon from the ground is about 0.5 deg.

Long wave infrared camera (LIR) : 10 micron (wavelength)

Field of View: 12.4 deg x 16.4 deg

Number of pixels: 248 x 328

.

Ultraviolet imager (UVI): 365 nm (wavelength)

Field of View: 12 deg x 12 deg

Number of pixels: 1024 x 1024

.

N.B. Left image is artificially colored.

1 micron camera (IR1) : 0.9 micron (wavelength)

Field of View: 12 deg x 12 deg

Number of pixels: 1024 x 1024

.

N.B. Left image is artificially colored.

Comparison of images in the same scale

.

N.B. Images are artificially colored (UVI image - blue; IR1 image - red)

Quelle: JAXA

-

Update: 9.12.2015

.

Venus Climate Orbiter “AKATSUKI” Inserted Into Venus' Orbit

December 9, 2015 (JST)

National Research and Development Agency

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) successfully inserted the Venus Climate Orbiter “AKATSUKI” into the orbit circling around Venus.

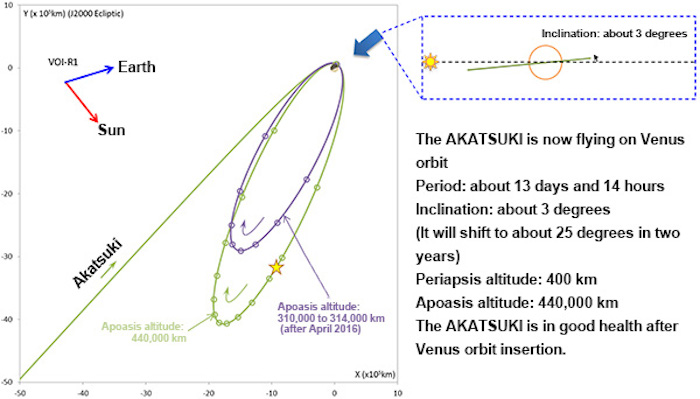

As a result of measuring and calculating the AKATSUKI’s orbit after its thrust ejection, the orbiter is now flying on the elliptical orbit at the apoapsis altitude of about 400 km and periapsis altitude of about 440,000 km from Venus. The orbit period is 13 days and 14 hours. We also found that the orbiter is flying in the same direction as that of Venus’s rotation.

The AKATSUKI is in good health.

We will deploy the three scientific mission instruments namely the 2μm camera (IR2), the Lightning and Airglow Camera (LAC) and the Ultra-Stable oscillator (USO) and check their functions. JAXA will then perform initial observations with the above three instruments along with the three other instruments whose function has already been confirmed, the Ultraviolet Imager (UVI), the Longwave IR camera (LIR), and the 1μm camera (IR1) for about three months. At the same time, JAXA will also gradually adjust the orbit for shifting its elliptical orbit to the period of about nine days. The regular operation is scheduled to start in April, 2016.

Orbit calculation result (as of Dec. 9)

Periapsis altitude About 400 km

Apoasis altitude About 440,000 km

Inclination About 3 degrees against Venus’ revolution plane

Period About 13 days and 14 hours

.

Orbit pattern diagram

.

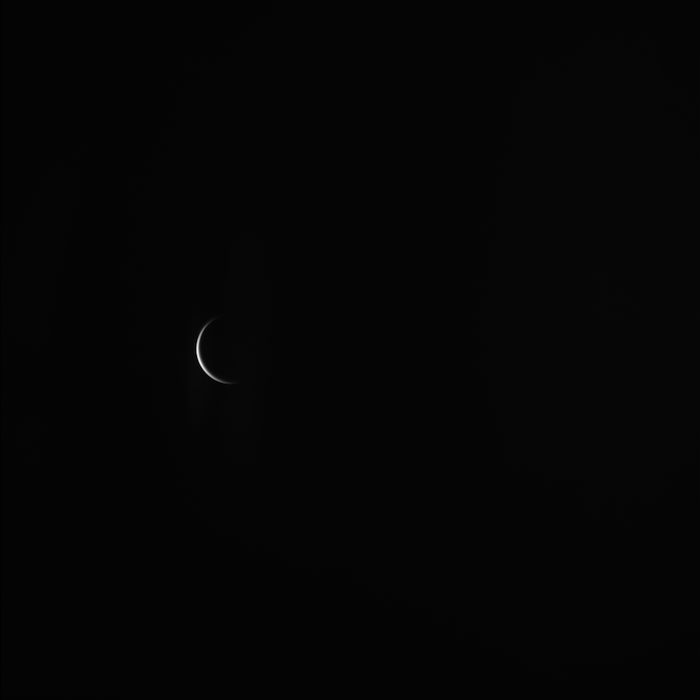

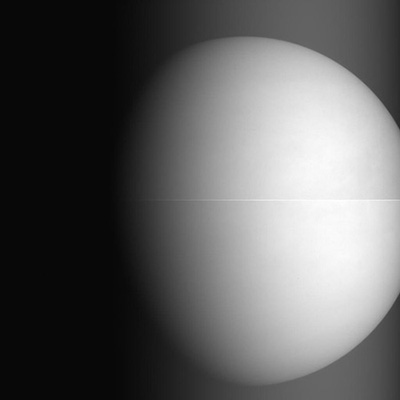

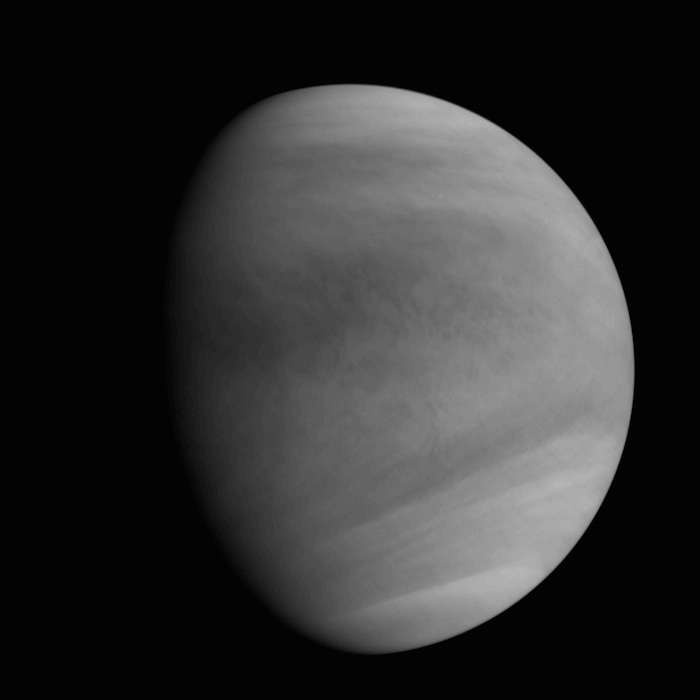

Venus image taken by AKATSUKI immediately after its attitude control ejection.

By 1μm camera (IR1) at around 1:50 p.m. on Dec. 7 (Japan Standard Time) at the Venus altitude of about 68,000 km

.

By Longwave IR camera (LIR) at around 2:19 p.m. on Dec. 7 (Japan Standard Time) at the Venus altitude of about 72,000 km

.

By Longwave IR camera (LIR) at around 2:19 p.m. on Dec. 7 (Japan Standard Time) at the Venus altitude of about 72,000 km

Quelle: JAXA

.

Update: 8.01.2016

.

- Second Chance at Venus Orbit for Wandering Akatsuki Probe

- On December 7, 2015, the Akatsuki probe entered into orbit around Venus, five years after its first, failed attempt. The probe was launched by JAXA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, in 2010, a year when the successful return of Hayabusa from its mission to gather asteroid dust changed the attitude of the Japanese public toward space exploration.

- .

Routine Successes Soon Forgotten

NASA’s crewed Apollo Program missions, from Apollo 7 to Apollo 17, were all successful in various ways. Neil Armstrong’s “one giant leap for mankind” on the surface of the moon during the Apollo 11 mission was instant history and unforgettable. On the other hand, the drama of the Apollo 13 mission, when instrument failure forced the lunar landing to be abandoned, lay in how close it came to disaster before the astronauts safely returned to Earth. The original recording of its descent and later re-creation on screen in the eponymous film starring Tom Hanks have helped to fix the story in people’s memories.

By contrast, the other missions are not so memorable, despite the further successful moon landings, spacewalks, and long-term stays in orbit. One could say that they have been forgotten by the general public perhaps because their success was achieved so smoothly.

Dawn Probe Orbits Venus

On December 7, Japan’s Akatsuki probe finally entered the orbit of Venus; the insertion was found to have been successful two days later. Akatsuki, meaning “Dawn,” was initially launched on an H-IIA rocket in 2010, but engine failure meant that its first attempt to orbit Earth’s neighbor came to nothing. Five years later it got a second chance, allowing Japan to follow the former Soviet Union, the United States, and Europe in getting a closer look at Venus. It is the first Japanese probe to orbit another planet.

The year 2010 having been a momentous one for the nation’s space program, many in Japan may not remember the Akatsuki launch on May 21. They must, however, recall the reentry into Earth’s atmosphere of the Hayabusa probe three weeks later on June 13. The Hayabusa capsule, which had completed a mission to gather dust from an asteroid, landed in the Australian outback, where it was recovered by a team of space scientists. The reentry itself was live-streamed in Japan on Ustream and Niconico, as well as by universities. Shōchiku, Tōei, and 20th Century Fox all produced films about Hayabusa and its unprecedented feat as the space program enjoyed an unusual boom. Under these circumstances, the attempt in December that year to get the Akatsuki into a Venus orbit caused unexpected interest, even though it failed.

The probe did not simply drift aimlessly through space in the five years that followed. Although its controls were damaged, its cameras and other observational equipment were still in working order, so it was able to gather scientific data while following an altered orbit with the aim of making a second attempt. Taking advantage of its positioning between the sun and Venus in March 2011, it was used to complete photometric observations of the planet. Then in June 2011, with the sun between Earth and Akatsuki, it transmitted radio waves to Earth with an ultrastable oscillator, obtaining data on how the waves were affected by plasma and solar winds emitted by the sun. The device was originally built for observing Venus, but was also fit for this purpose.

Even so, the five years spent voyaging through the solar system have taken their toll on Akatsuki. Its unplanned approach toward the sun exposed its equipment to high temperatures and there is no guarantee that these devices have not been damaged. Its main thrusters for inserting the probe into orbit were damaged five years ago and it now has to rely on smaller thrusters for adjusting its position. With these restraints, entering the orbit of Venus was like threading a needle.

.

.

Akatsuki took this picture of Venus at 2:19 pm on December 7 (JST) from an altitude of 72,000 kilometers. (Photo provided by JAXA.)

- .

- The Importance of Continuity

The time lag between Earth and probes in space makes them particularly difficult to control. With machines of such complexity, problems caused by human error are also expected to some degree. These constraints mean that rapid decisions have to be made about whether it is possible to complete an objective—and, if not, whether an alternative objective can be completed. Hayabusa is a case in point. The mission faced endless difficulties, but each time the members of the operating team used all their knowledge to get it back on track, ultimately bringing the capsule back for its stirring return to Earth.

From another perspective, there was an undeniable need to tackle the design faults in the Hayabusa mission that led to the misfiring of the probe’s engine, problems with the sampling equipment, and the failure to deploy the MINERVA (Micro/Nano Experimental Robot Vehicle for Asteroid) rover. The lessons learned in the course of dealing with these issues must be applied to future design as an essential part of pushing development forward. A sense of project continuity is required so that young researchers and technicians, including graduate students, can build up and carry over experience from the design to the operational stage and decision-making skills honed through meeting any problems that occur. As the time between projects stretches out, though, it is difficult to acquire the abilities gained from actually working on a mission. Unfortunately, budgets are limited and space research has to carry on regardless.

Success Now a Matter of Course

Around two weeks before Akatsuki achieved orbit, an H-IIA rocket carrying a communications and broadcast satellite for Telstar of Canada was launched. It was the first time Japan had turned its space technology to business purposes by carrying another country’s commercial satellite. The rocket’s second stage LE-5B engine also used unprecedented re-ignition technologies, which have a similar effect to hitting the gas in a car to climb a slope after coasting down a straight road. This allows the rocket to travel much farther through space, where there are no “gas stations,” and deliver satellites much closer to a stable orbit. The launch was very significant for Japan’s space business, but as a smoothly executed success, it did not attract much attention.

The Selene lunar orbiter popularly known as Kaguya was launched four years after Hayabusa, completing an almost perfect mission. It too was largely ignored as a routine success. It is ironic then that the recovery efforts for Hayabusa were highly praised, resulting as they did from problems that arose during the mission.

The overshadowing of Kaguya by the Hayabusa story and the lack of interest in the Telstar launch may not necessarily be bad developments, although they must be vexing for those involved in space exploration. Japan regularly carries out routine launches—everything from probes and orbiters to cargo ships for the International Space Station—and individual projects are quickly forgotten. Now that smooth successes have become expected, the once regular failed launches and fruitless efforts to get satellites into orbit are a rarity. The media no longer grumbles about the waste of taxpayers’ money on equipment that ends up in the sea or as useless space junk.

A Spirit of Tolerance

Apollo 13 did not complete its objective of landing on the moon, but it was still regarded as a “successful failure.” President Richard Nixon praised the crew as well as the efforts of the ground controllers who supported them on their return, awarding them the Medal of Freedom. The mission seems to have changed the thinking of American society and how people viewed space exploration.

Japan’s investigation of Venus, our “morning star” and “evening star,” will soon begin. Akatsuki, however, only has a design lifespan of four and a half years, and has sustained damage. It will soldier on until it loses its remaining strength. If it meets some dramatic end, it may win people’s affection even if it cannot complete its initial mission. On the other hand, if it completes its mission and then one day communications from the probe quietly cease, this will be another expected success, after which Akatsuki may well be forgotten.

.

It remains to be seen what will happen. The story of Hayabusa in 2010, however—the year when Akatsuki was launched—was one that stirred people’s hearts, despite the mission’s many failures, and one that seems to have fostered a spirit of tolerance in Japan for the space program when it battles on through difficulties and errors. It could be said that this tolerance spurred on Akatsuki’s successful second attempt.

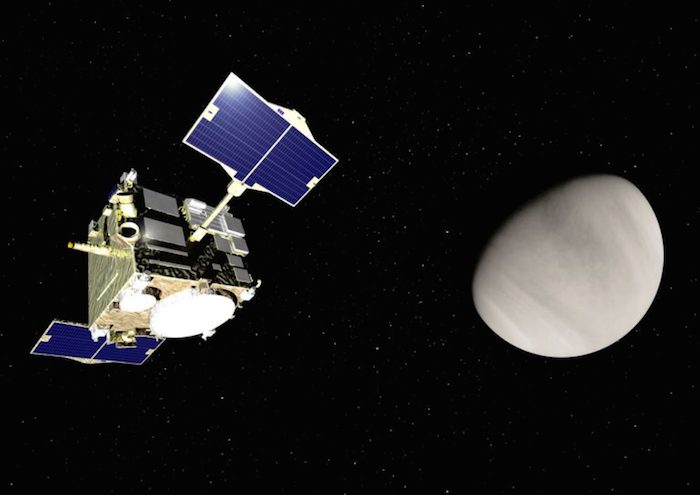

(Banner photo: An artistic rendering of the Venus Climate Orbiter Akatsuki. Image provided by JAXA.)

Quelle: nippon

.

Update: 13.04.2016

.

Rescued Japanese spacecraft delivers first results from Venus

Streaked acidic clouds and a bow shape in the atmosphere are among Akatsuki’s findings.

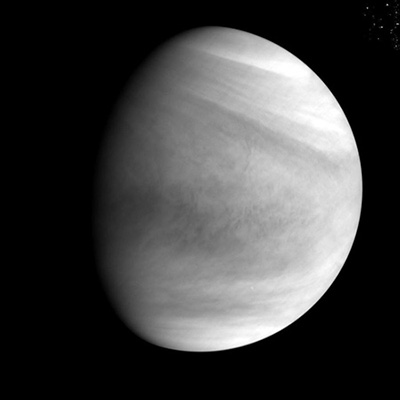

After an unplanned five-year detour, Japan’s Venus probe, Akatsuki, has come back to life with a bang. On 4–8 April, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) presented the first scientific results from the spacecraft since it was rescued from an errant orbit around the Sun and rerouted to circle Venus, four months ago. These include a detailed shot of streaked, acidic clouds and a mysterious moving ‘bow’ shape in the planet’s atmosphere.

Despite the probe’s tumble around the Solar System, its instruments are working “almost perfectly”, Akatsuki project manager Masato Nakamura, a planetary scientist at JAXA’s Institute of Space and Astronautical Science in Sagamihara, Japan, announced at the International Venus Conference in Oxford, UK. And if another small manoeuvre in two years’ time is successful, he said, the spacecraft might avoid Venus’s solar-power-draining shadow, and so be able to orbit the planet for five years, rather than the two it was initially assigned.

Akatsuki, which means ‘dawn’ in Japanese, launched in 2010 and was supposed to enter into orbit around Venus later that year to study the planet’s thick atmosphere. The mission would include looking for signs of active volcanos and other geology. But upon entry, a fault in a valve caused the probe’s main engine to blow, and the craft instead entered an orbit around the Sun. As Akatsuki passed near Venus in December, JAXA engineers managed to salvage the mission by instructing the craft’s much smaller, secondary thrusters to push it into a looping elliptical orbit around the planet. The results presented in Oxford were captured from this vantage point with a suite of five cameras that capture light ranging from infrared to ultraviolet.

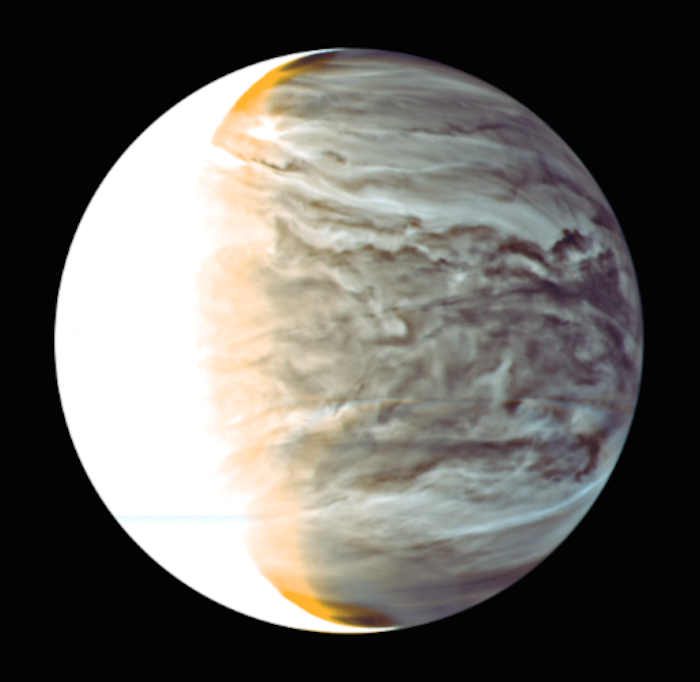

A highly detailed shot of dense layers within Venus’s sulfuric acid clouds elicited applause from the audience. The highest-quality infrared image of this view of Venus, it suggests that the processes that underlie cloud formation might be more complicated than thought, project scientist Takeshi Imamura told attendees.

And the team expects still better results to come. The image was taken from 100,000 kilometres away — more than 10 times the probe’s distance at its closest pass of Venus. “We will achieve better spatial resolution still,” said Takehiko Satoh, principal investigator for the probe’s 2-micrometre infrared camera, IR2, which took the image. “We promise to give a fantastic data set to the research community for years.”

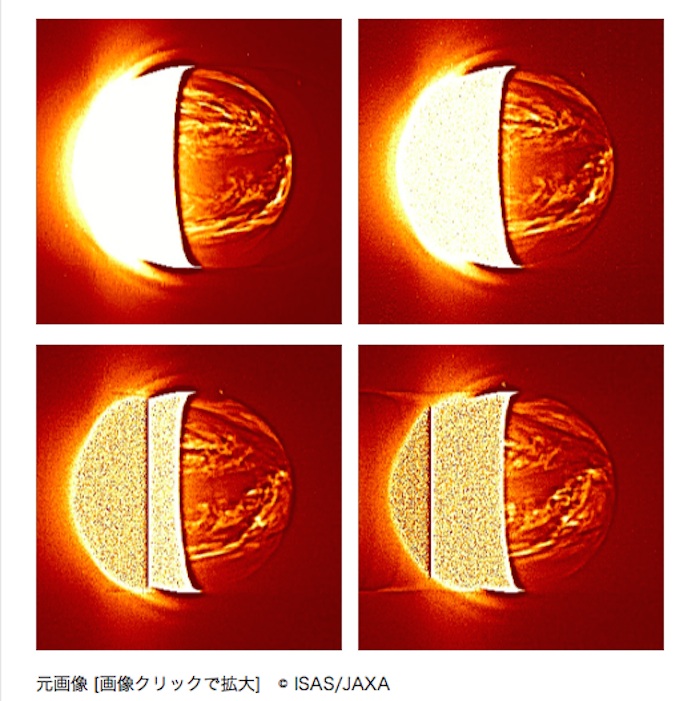

The bow shape, which was seen in thermal images taken using a long-wave infrared (LIR) camera, provided some intrigue. The moving cloud formation, which swept from pole to pole across the planet for days, seemed to rotate with Venus’s surface, rather than with its much quicker-moving atmosphere.

The motion suggests that the front could be linked to features on the ground, said Makoto Taguchi, who leads the LIR camera. Others at the conference were at a loss as to what may have caused it. “It’s certainly mysterious,” says planetary scientist Suzanne Smrekar of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Akatsuki’s success has cheered researchers, especially because it is now the only working probe deployed at Venus. “The mood is very good,” says Colin Wilson, a planetary scientist at the University of Oxford, UK. Akatsuki’s orbit — which was tweaked slightly on 4 April to give the probe the best chance of lasting for years to come, as well as to provide a good scientific vantage point — will allow it to survey Venus’s equator as originally planned. The resulting images will complement surveys of the planet’s poles from the European Space Agency’s Venus Express orbiter, which ended its mission in 2014.

But Akatsuki’s new lease of life comes with compromises, too. Its current 10.5-day operational orbit takes it almost 5 times as far from Venus at its most distant point than its original intended orbit (see ‘Orbital alteration’). Except for those taken during the short period when the probe sweeps close to the planet, images will be lower in resolution than planned. This means that studies that require detail, such as spotting flashes of lightning, will take longer. But the team said that it plans to make the best of the probe’s wide orbit to take whole-Venus images that track large-scale features over time.

.

The mission has also not shrugged off all consequences of its long and unexpected cruise around the Sun. One camera malfunctioned in January, probably because of gradual contamination of a helium coolant with water vapour over the years, said Satoh. Engineers have now fixed the problem by warming the coolant to disperse the vapour, but it took a while. “We had a painful blank of about a month,” says Satoh.

Planetary scientists outside of JAXA will have to wait a year from acquisition to access the data, but they are nonetheless excited by the probe’s initial success. Two Venus-based projects are among five proposals shortlisted by NASA for possible launch in the early 2020s. The agency is expected to decide by the end of December, and Venus missions could get a boost from Akatsuki’s success — especially if the orbiter finds intriguing features that require follow up, says Smrekar, who leads one of the Venus proposals that NASA is considering, the proposed VERITAS radar orbiter. “If they’re able to see new volcanism, for example, it definitely makes the case for going back to explore more fully,” she says.

Quelle: nature

- -

- Update: 18.05.2016

- .

Japanese orbiter officially begins science mission at Venus

Artist’s concept of Japan’s Akatsuki spacecraft at Venus. Credit: JAXA

-

Five months since a belated arrival at Venus, Japan’s Akatsuki spacecraft has officially started a modified scientific survey of the sweltering, shrouded planet’s atmosphere and climate.

The probe’s science cameras are collecting regular images of Venus’s exotic clouds, and Japanese engineers are optimistic Akatsuki can remain operational for at least two years, and perhaps through 2020.

Akatsuki braked into orbit around Venus in early December, five years later than originally planned after it missed an arrival opportunity in 2010.

Scientists checked out the orbiter’s science instruments since the craft arrived at Venus, and declared Akatsuki operational in April, according to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. One of the spacecraft’s instruments, the lightning and airglow camera, is still being calibrated before it shifts to regular observations, JAXA said.

Launched by a Japanese H-2A rocket in May 2010, Akatsuki survived an unplanned five-year cruise to Venus, passing closer to the sun and withstanding higher temperatures it was designed to endure after a propulsion failure thwarted an orbit insertion burn in December 2010.

A salt formation blocked an engine valve, starving Akatsuki’s main thruster of fuel during the critical firing to swing into orbit around Venus.

Five years later, when Akatsuki was again in the vicinity of Venus, the spacecraft fired its secondary attitude control thrusters to steer into orbit. But the smaller engines had less power than the probe’s primary thruster, driving Akatsuki into an orbit stretching nearly five times farther from Venus than originally intended.

A course correction burn April 4 slightly adjusted Akatsuki’s orbit to reach a peak altitude of 370,000 kilometers (about 230,000 miles), roughly the distance between the Earth and the moon. At the low end of its orbit, Akatsuki passes between 1,000 and 10,000 kilometers (620-6,200 miles) above Venus’s cloud tops.

The higher orbit will complicate the mission’s scientific observations, with Venus appearing much smaller to Akatsuki’s cameras. It also produces fewer opportunities for radio occultation measurements, which use radio signals passed between the spacecraft and Earth-based antennas to study the vertical structure of Venus’s atmosphere.

The orbiter’s lightning and airglow camera, conceived to take the first pictures of lightning flashes on Venus, can only collect images for about one hour during each 10.8-day orbit, when Akatsuki is in the shadow of the planet. The limited imaging windows for the lightning camera have extended the instrument’s calibration time, but scientists expect it to begin full science observations in June.

Takeshi Imamura, Akatsuki’s project scientist at JAXA’s Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, told a gathering of planetary scientists in Britain last month that the mission’s shortcomings could be overcome with more high-resolution imaging at the low point of Akatsuki’s orbit, and an extension of the probe’s operations beyond its original two-year lifetime through 2020.

Akatsuki, which means dawn in Japanese, is the only mission currently operating at Venus. It is also Japan’s first spacecraft to orbit another planet.

The craft is the first Venus mission dedicated to unraveling the planet’s complex atmosphere, with high-altitude super-rotating jet streams, thick clouds made of sulfuric acid and a blanket of heat-trapping carbon dioxide, driving surface temperatures to 900 degrees Fahrenheit (480 degrees Celsius), hot enough to melt lead.

.

One of Akatsuki’s infrared cameras took this image of the night side of Venus, the most detailed view of the planet’s nighttime clouds ever acquired. Credit: JAXA

-

Akatsuki carries three infrared cameras, each tuned to resolve a different layer in Venus’s atmosphere.

One of the imagers can see deep into the planet’s shroud of clouds and toxic haze to see Venus’s surface terrain. An early picture from the camera revealed Aphrodite Terra, a highland region near the planet’s equator so far only observed by radar surveys.

Another sensor in longwave infrared can detect the temperature of Venus’s cloud tops, while a two-micron imaging channel is suited for observations of the planet’s night side.

Akatsuki beamed back the most detailed global image ever captured of Venus’s night side clouds March 25. The six-second exposure, posted above, reveals previously unseen wave and stripe patterns.

“This is to date the most detailed global view of the night-side disk,” JAXA wrote in a description accompanying the image. “At 2.26 microns, spatially-inhomogeneous clouds appear as silhouette back-illuminated by thermal radiation from the hot lower atmosphere. Such images, combined with other cameras’ data, will be used to study the 3D structure and dynamics of Venus atmosphere.”

The longwave infrared camera spotted an unexpected bow-shaped cloud stretching thousands of kilometers running from the northern hemisphere to the southern hemisphere of the planet.

“This is the first time to learn (of) such a phenomenon,” JAXA said in a statement.

An ultraviolet camera aboard Akatsuki can help scientists study the origin of the planet’s clouds and track weather patterns as they move around the planet with jet stream winds moving at up to 400 kilometers per hour (250 mph).

Imamura said the processes responsible for the formation of Venus’s sulfuric acid clouds seem to be much more complicated than expected.

Scientists plan near-continous global imaging throughout Akatsuki’s mission, plus closeups when the spacecraft is near Venus, occasional searches for lightning and atmospheric profile measurements with the probe’s radio science platform.

Quelle: SN

-

Update: 13.06.2016

.

A movie of the Venus' night-side produced by IR2

This movie is produced from the IR2 2.26-μm images, acquired on 29 March 2016 at a distance of 0.36 million km. Original 4 images were acquired with 4-hour intervals from 16:03 JST (07:03 UT).

In 4 hours, the super-rotating clouds move by ~10 degrees. Such images are numerically derotated to produce intermediate images so that the resultant motion becomes smoother. Deformation, appearance and disapperance of clouds are obvious in this movie. As the mission enters the "nominal" observing phase, we plan to shorten the intervals to 2 hours or even shorter so the high-definition movies will definitely help understanding of the Venus atmosphere.

.

Quelle: JAXA

6709 Views