.

7.11.2014

.

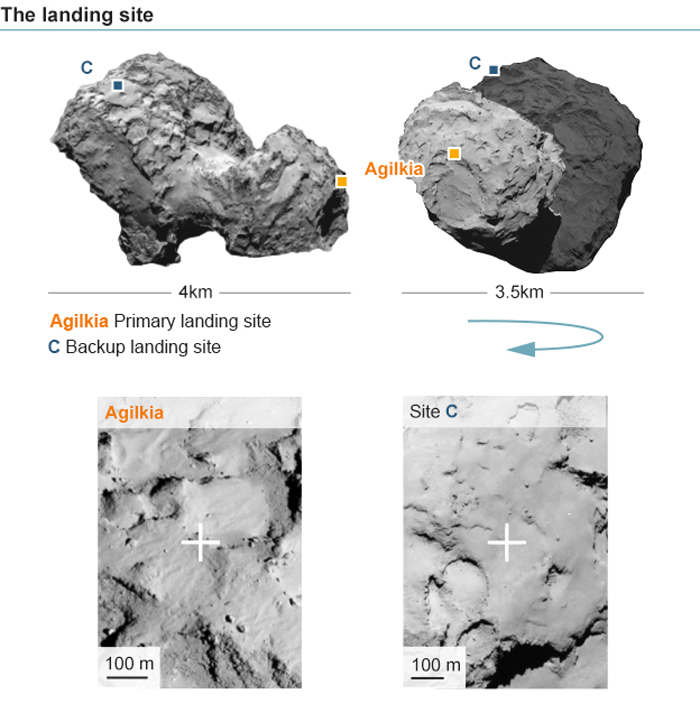

However, the one square kilometre site contains cliffs and crevices and has huge boulders - any of which could scupper a landing.

Agilkia has good lighting conditions, which for Philae means having some periods to recharge its solar-powered batteries and periods of darkness to cool its systems. Site C has been selected as a back-up.

Getting closer to the unusually shaped comet has given us its dimensions, but analysis has also revealed other details:

Comet's rotation: 12.4 hours Mass: One trillion kg (or 10 billion tonnes) Density: 400kg per cubic metre (the same as some woods) Volume: 25 cubic km

Colour: Charcoal - based on its albedo, or the amount of incident light it reflects back into space.

.

Separation and landing

"The point though is not merely to watch the comet from a safe distance, but to get down on the ground and actually touch the object." Prof Ian Wright, Open University

The landing is set for 12 November. Rosetta will release Philae at 08:35 GMT from a distance of 22.5km from the centre of 67P. An inaccuracy of a few millimetres per second in Rosetta's orbit could result in Philae completely missing the comet.

The descent, monitored from Esa's mission control in Darmstadt, Germany, is expected to last about seven hours.

Because the event is taking place 510 million km from Earth, communication between Rosetta and controllers takes 28 minutes and 20 seconds each way. As a consequence, confirmation of separation is not expected until about 09:03 GMT and of the landing until just after 16:00 GMT.

There will be no steering of the lander down to the comet's surface - once released, it is on a path of its own.

"We need a certain amount of luck to end up in a nice spot," Paolo Ferri, head of mission operations, said.

Although the date has been set, the Rosetta team will have to make a series of Go or No-Go decisions before the landing attempt on 12 November.

"If any of the decisions result in a No-Go, then we will have to abort and revise the timeline accordingly for another attempt, making sure that Rosetta is in a safe position to try again," says Fred Jansen, Esa's Rosetta mission manager.

.

1: Release from Rosetta

Rosetta will push the Philae lander away when the spacecraft is about 22.5km from the comet's centre. Rosetta needs to release Philae at exactly the right place in time and space to be sure of putting the little robot on the correct path to the comet

2: Descent

The descent to the comet's surface is expected to take about seven hours. On the way down, Philae will take pictures of the comet and start taking measurements of the environment around the comet

3: Comet activity

The comet activity on the day - throwing out gas and dust or even the splitting up of the comet itself - cannot be predicted. The descending robot will just have to cope with whatever is chucked at it

4: Landing zone

The chosen landing area is not perfectly flat, but most slopes are at an angle of less than 30 degrees. There are some boulders that could pose a problem if Philae hits them, however

5: Touchdown

When the lander hits the surface - at walking pace - footscrews will drill into the surface and harpoons will be used as anchors. A thruster on top of Philae will also gently push the robot into the surface to stop it bouncing off into space. If the surface is very soft, the screws may not secure the lander. If it is very hard, they may not penetrate it at all

.

Once on the surface, Philae can get to work. The lander will take a panoramic photo of its surroundings using its onboard micro-cameras. Next, about an hour after touchdown, the first sequence of surface science experiments will begin, and will last for 60 or so hours.

The Rosetta orbiter will continue to study the comet using its 11 science instruments - but it will also be relaying data from Philae's instruments. Radio waves sent from Philae to Rosetta when the orbiter spacecraft is on the opposite side of the comet will help determine the structure of the comet's interior.

Drills, ovens, cameras and sensors onboard Philae will analyse everything from the surface composition and temperature to the presence of amino acids - essential building blocks in the chemistry of life.

.

1: Cameras - Philae's CIVA imaging system has cameras that will take panoramas of the comet's surface terrain. The download-looking ROLIS system will spy the comet on descent, and take close-ups once landed

2: Nucleus probe - CONSERT - will use radio waves to probe the internal structure of the comet nucleus

3: Footscrews - Ice screws on the feet of Philae's legs will drill down into the comet to secure the lander. Problems could arise if the surface is too hard or too soft

4: Sample drill - SD2 - Sample and Distribution Device - will drill more than 20cm into the surface, collect samples and deliver them to onboard laboratory equipment COSAC and PTOLEMY for analysis.

5: Harpoons - Immediately after touchdown, a harpoon will be fired to anchor Philae to the comet's surface and prevent it bumping off because of the comet's weak gravity

6: Surface probe - MUPUS - Sensors on the lander's anchor, probe and exterior will measure the density, thermal and other properties of the surface and subsurface

Prof Ian Wright, of the Open University, is the principal investigator of the Ptolemy instrument. He says the Rosetta mission is already a success, whatever happens with the landing - which everyone on the project knows is a risky venture.

"As things stand, the orbiter will continue to shadow the comet until the end of next year. This will be an opportunity to observe how the body responds to its close passage to the Sun," he said.

"The point though is not merely to watch the comet from a safe distance, but to get down on the ground and actually touch the object. For those of us who are used to handling and analysing samples in the lab it is the only way to study it. We realise that we may ultimately end up with nothing but that is the nature of exploration."

.

After the initial science sequences, longer-term studies are planned, depending on how well Philae's batteries are able to recharge. This could be affected by how much dust gathers on its solar panels.

As the mission continues and the comet journeys closer to the Sun, temperatures inside the lander will get so hot that its batteries and electronics will stop working. This could be around March 2015.

But even after Philae's mission ends, Rosetta will continue its escort and remote analysis of the comet for a few more months.

.

August 2014: Rendezvous with comet - Rosetta reaches Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko after a 10-year journey. The craft starts orbiting the comet and identifies suitable sites for the Philae lander.

November 2014: First Science Sequence - After landing on the comet, Philae's first few days are spent running through a predetermined set of experiments.

December 2014: Long-term science - The team hopes Philae will continue working and recharging its batteries, to continue its observations despite its temperature constraints on the comet.

March 2015: Lander limits - Philae could be affected by increasing temperatures on the comet and may be at risk of layers of dust hampering the effectiveness of its solar panels.

August 2015: Perihelion - The comet reaches its closest position to the Sun. Rosetta will be measuring the level of activity as the icy object enters its most active phase.

Quelle: BBC

.

Update: 10.11.2014

.

Rosetta: Die dunkle Seite des Kometen

Ein Teil des Kometen 67P liegt seit Monaten in völligem Dunkel. Licht, das Staubpartikel in der Umgebung des Kometen streuen, erlaubt nun einen ersten Blick auf diese Region.

.

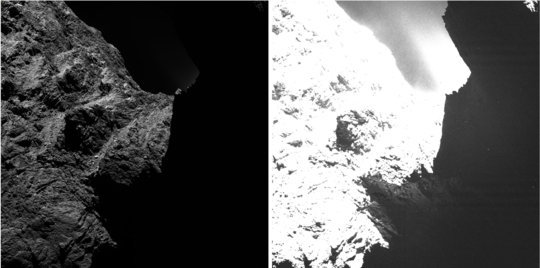

OSIRIS, das wissenschaftliche Kamerasystem an Bord der ESA-Raumsonde Rosetta, hat einen ersten Blick auf die Südseite des Kometen 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko geworfen. Seit Monaten bereits ist diese Seite durchgängig der Sonne abgewandt, so dass es nach wie vor unmöglich ist, dort Strukturen oder auch nur grobe Formen zu erkennen. Nur das Streulicht von Staubpartikeln in der Umgebung des Kometen lässt einige Oberflächenstrukturen erahnen.

Seitdem die ESA-Raumsonde Rosetta im August dieses Jahres am Kometen 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko eingetroffen ist, hat das Kamerasystem OSIRIS den Großteil der Oberfläche kartiert. Auf diese Weise wurden beeindruckende Oberflächenstrukturen wie etwa steile Klippen und Brocken sichtbar. Die Südseite von 67P ist jedoch noch völlig unerforscht. Da die Rotationsachse des Kometen nicht senkrecht auf der Bahnebene steht, sondern gekippt ist, liegen Teile der Oberflächen zeitweise in dauerhaftem Dunkel. Seit einigen Monaten erfährt die Südseite des Kometen eine solche Polarnacht – vergleichbar mit den Wochen völliger Dunkelheit in den Polarregionen der Erde.

.

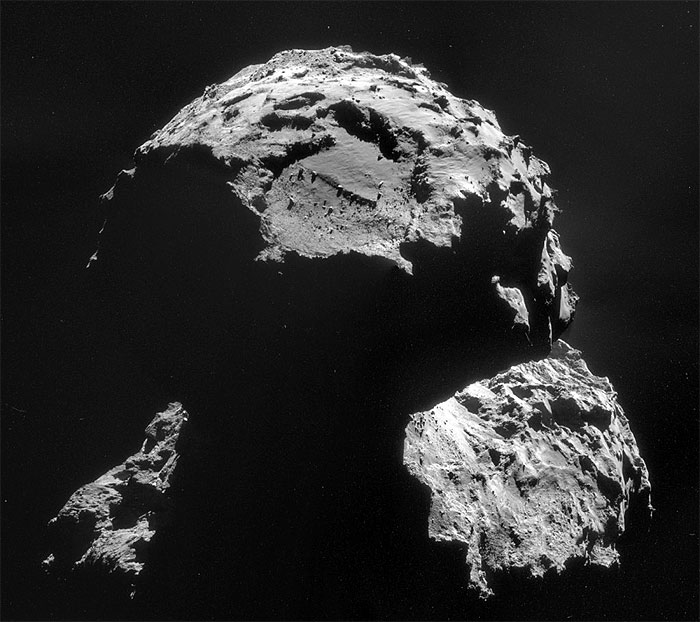

Ein Bild des Kometen 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, das am 30. Oktober 2014 vom Kamerasystem OSIRIS aus einer Entfernung von ... [mehr]

ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

-

Gleichzeitig könnte die dunkle Seite des Kometen helfen, die Aktivität des Körpers besser zu verstehen. „Wenn 67P seinen sonnennächsten Punkt erreicht, trennen ihn nur etwa 186 Millionen Kilometer von unserem Zentralgestirn. In dieser Phase wird gerade diese Südseite beleuchtet und ist somit besonders hohen Temperaturen und starker Strahlung ausgesetzt“, erklärt der Leiter des OSIRIS-Teams, Holger Sierks vom Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung (MPS) in Göttingen. Wissenschaftler vermuten deshalb, dass diese Seite am stärksten von der Aktivität des Kometen gezeichnet ist. „Wir sind schon sehr gespannt auf den Mai nächsten Jahres. Dann endet die Polarnacht und wir können die Südseite endlich genau betrachten“, so Sierks.

Bis dahin bietet ein Bild aus den vergangenen Wochen einen kleinen Vorgeschmack. Darin beleuchtet das Streulicht, das Staubteilchen in der Koma des Kometen reflektieren, seine dunkle Seite, so dass sich einige Oberflächenstrukturen erahnen lassen.

.

Ein seltener Blick auf die dunkle Seite des Kometen 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Durch das Licht, das Staubteilchen aus ... [mehr]

ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

.

„Einer normalen Kamera würde diese winzige Lichtmenge kaum weiterhelfen”, erklärt OSIRIS-Teammitglied Maurizio Pajola vom Center of Studies and Activities for Space der Universität Pardua in Italien, der das Bild als erster entdeckte. Während gewöhnliche Kamaras Informationen in 8 Bits pro Pixel speichern und somit nur 256 verschiedene Graustufen unterscheiden können, ist OSIRIS eine 16-Bit-Kamera. Das bedeutet, dass ein einzelnes Bild mehr als 65000 Graustufen enthalten kann – deutlich mehr als etwa ein Computerbildschirm in der Lage ist darzustellen. „Aus diesem Grund kann OSIRIS schwarze Oberflächen, die dunkler als Kohle sind, und weiße Regionen so hell wie Schnee in ein und demselben Bild abbilden“, so Pajola.

Die OSIRIS-Wissenschaftler nutzen diese hohe dynamische Bandbreite nicht nur, um in das Dunkel der Polarnacht zu blicken, sondern auch, um Informationen über Regionen zu erhalten, die in manchen Bildern für kurze Zeit im Schatten liegen.

Rosetta ist eine Mission der Europäischen Weltraumagentur ESA mit Beiträgen der Mitgliedsstaaten und der amerikanischen Weltraumagentur NASA. Rosettas Landeeinheit Philae wurde von einem Konsortium unter Leitung des Deutschen Zentrums für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR), des Max-Planck-Instituts für Sonnensystemforschung (MPS) und der französischen und italienischen Weltraumagentur (CNES und ASI) zur Verfügung gestellt. Rosetta wird die erste Mission in der Geschichte sein, die einen Kometen anfliegt, ihn auf seinem Weg um die Sonne begleitet und eine Landeeinheit auf seiner Oberfläche absetzt.

Das wissenschaftliche Kamerasystem OSIRIS wurde von einem Konsortium unter Leitung des Max-Planck-Instituts für Sonnensystemforschung in Zusammenarbeit mit CISAS, Universität Padova (Italien), Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille (Frankreich), Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucia, CSIC (Spanien), Scientific Support Office der ESA (Niederlande), Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial (Spanien), Universidad Politéchnica de Madrid (Spanien), Department of Physics and Astronomy of Uppsala University (Schweden) und dem Institut für Datentechnik und Kommunikationsnetze der TU Braunschweig gebaut. OSIRIS wurde finanziell unterstützt von den Weltraumagenturen Deutschlands (DLR), Frankreichs (CNES), Italiens (ASI), Spaniens (MEC) und Schwedens (SNSB).

Quelle: MAX-PLANCK-GESELLSCHAFT, MÜNCHEN

.

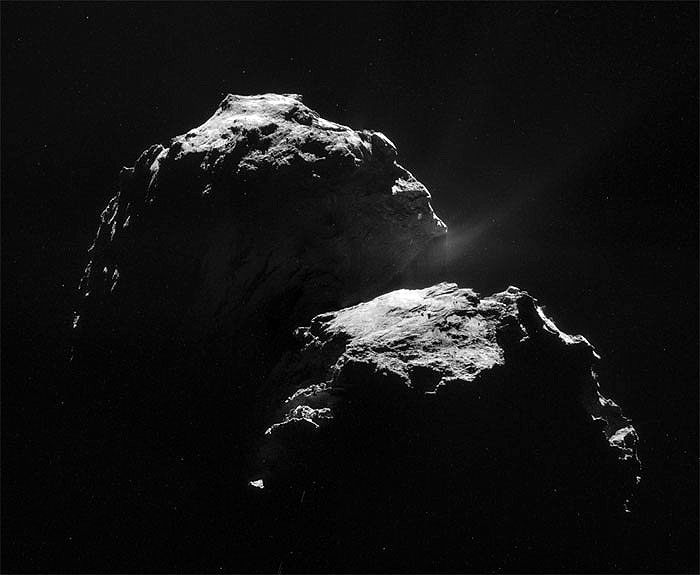

COMETWATCH – 4 NOVEMBER

This NAVCAM mosaic comprises four individual images taken on 4 November from a distance of 31.8 km from the centre of Comet 67P/C-G. The image resolution is 2.7 m/pixel, so each original 1024 x 1024 pixel frame measured 2.8 km across. The mosaic has been slightly rotated and cropped, and measures roughly 4.6 x 3.8 km.

.

Four image NAVCAM mosaic comprising images taken on 4 November. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

This mosaic was relatively tricky to make, given the lack of features in some of the overlap regions and some rotation of the comet between images. But as always, the individual images have also been made available below to allow you to check on the accuracy of the mosaicing.

The larger lobe of the comet is seen in the foreground and the smaller lobe behind (Note: the original post had this the wrong way round, sorry!). As with the OSIRIS image posted yesterday, we are looking into deep shadows on the small lobe, below the 'neck' of the comet. However, the brightly sunlit parts of the comet reflect enough light into the shadows to reveal hints of the features there, with the help of some image processing to bring out the full dynamic range.

Emission from gases escaping from the nucleus of 67P/C-G is also visible on the right side of the image, although it is not immediately obvious in this picture where the source of the emission is. Finally, there are many small white blobs in the image which could well be real objects in the vicinity of the comet rather than cosmic ray events hitting the detector.

.

COMETWATCH 6 NOVEMBER – TARGET LOCKED!

This four-image NAVCAM mosaic comprises images taken on 6 November from a distance of 30.5 km from the centre of Comet 67P/C-G.

.

Four image mosaic of Comet 67P/C-G comprising images taken on 6 November. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

The image resolution is 2.6 m/pixel. The mosaic has been slightly rotated and cropped, and measures 3.7 x 3.2 km. Due to rotation and translation of the comet during the image taking sequence, making a mosaic involves some compromises. However, as always, the individual images have also been made available below to allow you to check the accuracy of the mosaicing and intensity matching.

The Agilkia landing site can be seen at the ‘top’ of the image ‘above’ the easily recognisable depression that characterises the smaller of the comet’s two lobes.

.

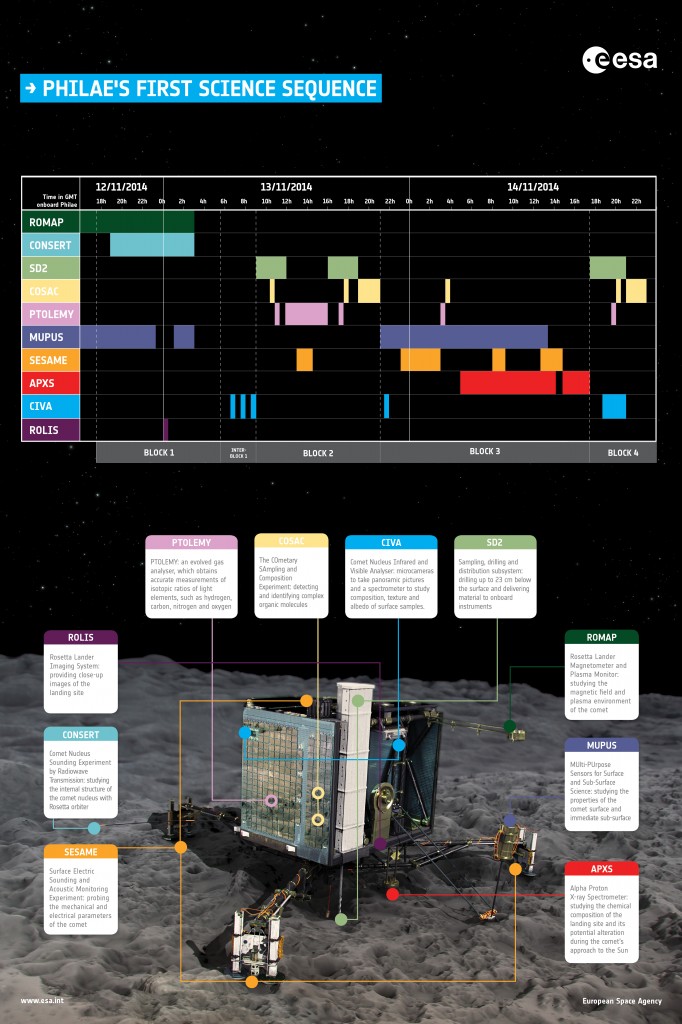

PHILAE’S FIRST SCIENCE SEQUENCE TIMELINE

If you were wondering what Philae is going to do once on the comet, here is a timeline of the lander's science operations during the first 2.5 days on the surface of 67P/C-G.

The timeline includes activities after touchdown, but it does not cover the experiments conducted during the seven-hour descent or immediately upon touchdown and in the 40 minutes after (which were already summarised in a previous post about the landing timeline). Details about the individual instruments are provided below.

.

The sequence of experiments is divided up into ‘blocks’. These follow a certain order because some measurements require Philae’s ‘body’ to be rotated, lifted or lowered before performing the next set. For example, during the ‘inter-block’, Philae will make these movements and take a new panoramic image.

The time is given in GMT on the lander; the lander relays data to the orbiter for storage and is queued for transmission to Earth. The one-way signal travel time Rosetta and Earth during 12–14 November is about 28.5 minutes.

The duration of the first science sequence that can actually be executed depends on the lifetime of the primary battery. If solar power is available to recharge the secondary battery then this may mean the full sequence can be executed. The ‘long-term science’ phase, which also depends on how long it takes for the secondary battery to recharge, is not included in this graphic; this phase could last until March 2015.

.

HIGHLIGHTS – MEDIA BRIEFING 10 NOVEMBER

We've just finished the first media briefing in the Press Centre at ESOC.

Media briefing at ESOC 10 Nov Credit: BBC/J. Amos

We just finished today's 15:00CET media briefing in the Press Centre at ESOC. The briefing was given by Flight Director Andrea Accomazzo, Rosetta Spacecraft Operations Manager Sylvain Lodiot, Project Scientist Matt Taylor, all from ESA, and DLR's Stephan Ulamec, project manager for Philae. Here is a summary:

The Rosetta spacecraft and Philae lander are in great shape

The commands to control the Philae lander are already uploaded

Today, the mission operations team at ESOC including the flight dynamics specialists are planning the spacecraft activities for tomorrow, and these will be translated into on-board commands and uploaded overnight

The timing for the Wednesday morning burn (now set for 07:35-08:35CET) is known to only about 30 minutes right now (see the landing timeline)

A final pre-delivery orbit determination will be done by teams tomorrow, and then we will know when final the pre-delivery burn will take place

For the Orbiter & Lander mission teams, there are a series of GO/NOGO decision points between tomorrow night & separation on Wednesday, now set for 10:03CET

The Lander will be switched on this evening and the control team will start warming it up and getting ready

Matt Taylor explained:

-- This week marks an 'epoch in the mission'; once we're past landing, we start full-on science; we're all 'GO'

-- Answering a query on surface texture: We know a bit more than we did before. It's a bit warmer than we initially thought; we're analysing data from several instruments; it's a more dusty surface material somewhere between hard-packed snow and cigarette ash; there are variations, but we're seeing this across the planned landing site.

When asked how we know we've landed, S. Ulamec explained: We see telemetry signals telling us we've touched the surface and that the harpoons have fired. He adds that it will take 'several minutes' to analyse the lander telemetry to confirm landing. One possible problem could be that Philae has landed, but that the harpoons have not anchored; that's why we need to look carefully at the telemetry.

When asked if we've seen any comet activity that may affect landing plans, S. Ulamec explained: If we see the comet break up, then we have a NOGO Seriously, we've seen no new activity affecting plans for landing.

The first science sequence lasts about 2.5 days (depending on battery life). If solar power recharges the batteries, we go into long-term surface science

In summary, everything is in great shape and we are counting down to an exciting and crucial delivery day.

Quelle: ESA

5731 Views