.

25.07.2014

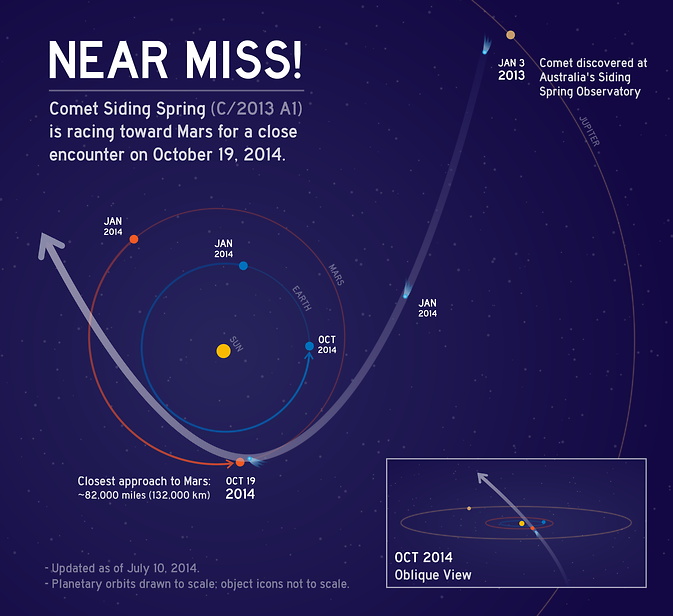

This graphic depicts the orbit of comet C/2013 A1 Siding Spring as it swings around the sun in 2014. On Oct. 19, the comet will have a very close pass at Mars. Its nucleus will miss Mars by about 82,000 miles (132,000 kilometers).

.

NASA is taking steps to protect its Mars orbiters, while preserving opportunities to gather valuable scientific data, as Comet C/2013 A1 Siding Spring heads toward a close flyby of Mars on Oct. 19.

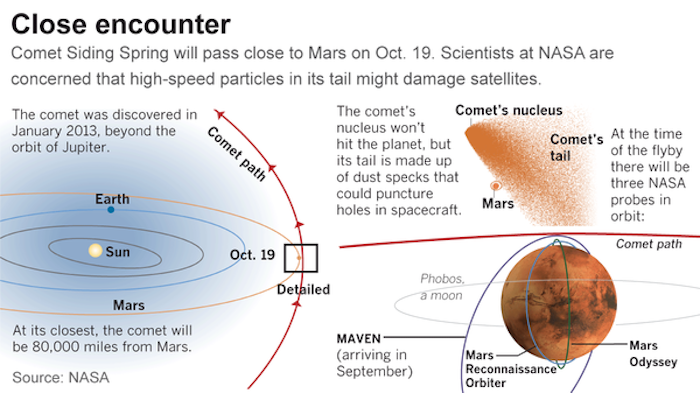

The comet’s nucleus will miss Mars by about 82,000 miles (132,000 kilometers), shedding material hurtling at about 35 miles (56 kilometers) per second, relative to Mars and Mars-orbiting spacecraft. At that velocity, even the smallest particle -- estimated to be about one-fiftieth of an inch (half a millimeter) across -- could cause significant damage to a spacecraft.

NASA currently operates two Mars orbiters, with a third on its way and expected to arrive in Martian orbit just a month before the comet flyby. Teams operating the orbiters plan to have all spacecraft positioned on the opposite side of the Red Planet when the comet is most likely to pass by.

"Three expert teams have modeled this comet for NASA and provided forecasts for its flyby of Mars," explained Rich Zurek, chief scientist for the Mars Exploration Program at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. "The hazard is not an impact of the comet nucleus, but the trail of debris coming from it. Using constraints provided by Earth-based observations, the modeling results indicate that the hazard is not as great as first anticipated. Mars will be right at the edge of the debris cloud, so it might encounter some of the particles -- or it might not."

During the day's events, the smallest distance between Siding Spring's nucleus and Mars will be less than one-tenth the distance of any known previous Earthly comet flyby. The period of greatest risk to orbiting spacecraft will start about 90 minutes later and last about 20 minutes, when Mars will come closest to the center of the widening dust trail from the nucleus.

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) made one orbit-adjustment maneuver on July 2 as part of the process of repositioning the spacecraft for the Oct. 19 event. An additional maneuver is planned for Aug. 27. The team operating NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter is planning a similar maneuver on Aug. 5 to put that spacecraft on track to be in the right place at the right time, as well.

NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft is on its way to the Red Planet and will enter orbit on Sept. 21. The MAVEN team is planning to conduct a precautionary maneuver on Oct. 9, prior to the start of the mission's main science phase in early November.

In the days before and after the comet's flyby, NASA will study the comet by taking advantage of how close it comes to Mars. Researchers plan to use several instruments on the Mars orbiters to study the nucleus, the coma surrounding the nucleus, and the tail of Siding Spring, as well as the possible effects on the Martian atmosphere. This particular comet has never before entered the inner solar system, so it will provide a fresh source of clues to our solar system's earliest days.

MAVEN will study gases coming off the comet's nucleus into its coma as it is warmed by the sun. MAVEN also will look for effects the comet flyby may have on the planet’s upper atmosphere and observe the comet as it travels through the solar wind.

Odyssey will study thermal and spectral properties of the comet's coma and tail. MRO will monitor Mars’ atmosphere for possible temperature increases and cloud formation, as well as changes in electron density at high altitudes. The MRO team also plans to study gases in the comet’s coma. Along with other MRO observations, the team anticipates this event will yield detailed views of the comet’s nucleus and potentially reveal its rotation rate and surface features.

Mars' atmosphere, though much thinner than Earth's, is thick enough that NASA does not anticipate any hazard to the Opportunity and Curiosity rovers on the planet's surface, even if dust particles from the comet hit the atmosphere and form into meteors. Rover cameras may be used to observe the comet before the flyby, and to monitor the atmosphere for meteors while the comet's dust trail is closest to the planet.

Observations from Earth-based and space telescopes provided data used for modeling to make predictions about Siding Spring's Mars flyby, which were in turn used for planning protective maneuvers. The three modeling teams were headed by researchers at the University of Maryland in College Park, the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, and JPL.

Quelle: NASA

.

Update: 4.08.2014

.

NASA braces Mars orbiters for close comet flyby

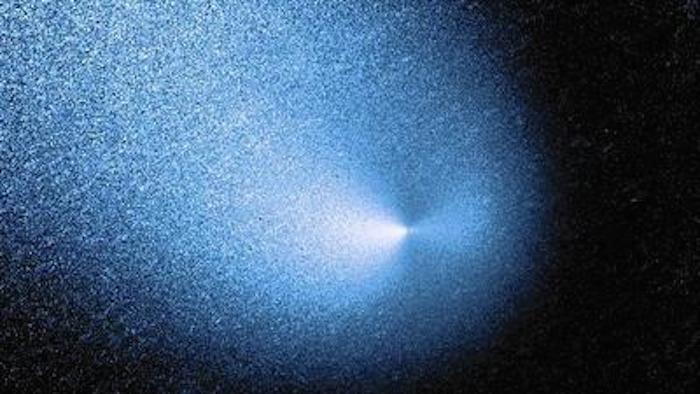

A camera on NASA's Hubble Space Telescope captured comet C/2013 A1, also known as Siding Spring. (NASA)

.

They are LITERALLY specks of dust, tiny bits of primordial material that wouldn't be visible to the naked eye.

But for spacecraft in orbit around Mars, they could become minuscule agents of destruction.

These dust particles will come hurtling past the Red Planet on Oct. 19, riding on the coattails of Comet Siding Spring. They'll blow by at an incredible 35 miles per second — 25 times faster than an armor-piercing projectile fired from a tank. And there could be millions of them.

At that velocity, they'll have the power to poke a hole in a spacecraft's gas line or crack a glass lens. They could knock out a computer board or take out a few cells on a solar panel.

And that's why scientists and engineers at NASA are nervous.

"They are essentially little cannonballs and bullets flying around, and they could do real damage," said Richard Zurek, chief scientist for the Mars Program Office at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

.

The three vulnerable orbiters cost THE AGENCY more than $1.5 billion to build and deploy. Since they're millions of miles from Earth, patching them up if they get broken is not an option.

So scientists are going to play a high-stakes game of hide and seek.

The stream of dust particles will be quite diffuse. Comet modelers have calculated that only one particle will pass through any given square kilometer of space.

"The typical area of a spacecraft is five square meters, so it doesn't sound like much risk," Zurek said. "But these are chances we would rather not take."

C/2013 A1, as the comet is formally known, was first spotted by an observatory in Australia on Jan. 3, 2013. Back then, it was still pretty far away, out past the orbit of Jupiter.

Based on its trajectory, scientists believe it originated in the Oort cloud, an unseen collection of icy bodies at the edge of the solar system.

Long-period comets like Siding Spring are made up of the detritus from the earliest days of the solar system. They are frozen time capsules from the era of planet formation, which is why scientists are eager to study them.

Siding Spring's nucleus is thought to be about half a mile across and contains gas, water and dust that has been in a deep freeze for billions of years. As it flies closer to the sun, the increase in radiation causes the ice to sublimate, releasing ancient gas and dust that follow the comet in a long tail.

The NASA spacecraft orbiting Mars are considerably newer additions to the solar system.

Odyssey arrived in 2001 to study the surface composition of the planet and its subsurface ice, taking measurements to help scientists understand what kind of radiation exposure humans would face if they visited Mars.

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter joined Odyssey in 2006. It studies the history of water on the Red Planet.

A third satellite, known as MAVEN, will reach Mars in September. It was designed to help scientists understand how Mars lost its water and atmosphere to space.

Like most of the spacecraft NASA sends into space, these three are made primarily of lightweight materials like titanium and aluminum. That makes them cheaper to launch, but it also makes them sitting ducks for a speeding smidge of dust.

Within a few weeks of Siding Spring's discovery, researchers at JPL's Near-Earth Object Program determined that it would come very close to Mars — possibly slamming into the rocky planet.

A few months and several data points later, however, that possibility was ruled out. The NEO team determined that Siding Spring's nucleus would get as close as 80,000 miles from Mars, or 10 times closer than any known comet has come to Earth.

"This is a once-in-a-several-million-year event," said program manager Don Yeomans. "If it were coming this close to Earth, it would be a scientific bonanza, plus a global celestial display."

When Zurek first heard that a comet was heading toward Mars, he was thrilled. Scientists think that cometary collisions delivered water to ancient Earth, Mars and perhaps other planets, so they are eager for any chance to study them.

"As a scientist I thought this could be really exciting," he said. "If the comet hit the planet, you would see an explosion and all this debris would go SHOOTING up into the atmosphere before raining back down to the surface."

But his enthusiasm quickly turned to dismay.

"I thought, 'Wait, we've got two rovers and two orbiters working away up there, plus another orbiter arriving in a few weeks,'" Zurek said. "Maybe this is a bad thing."

Zurek and his team realized the rovers, Opportunity and Curiosity, would be fine. The Martian atmosphere is less than 1% as thick as the atmosphere on Earth, but it would still be enough to burn up any incoming dust particles, creating a Martian meteor shower.

The orbiters would get no such protection. Though they would be a safe distance from Siding Spring's nucleus, they might share space with the cloud of tiny dust particles that make up the comet's tail.

Three separate teams of computer modelers were called in to figure out how fast the dust behind the comet is likely to TRAVEL, and how close it will get to the spacecraft.

All three models predict that the entire planet will spend a few hours engulfed in the outer layer of Siding Spring's coma, a CLOUD of gas that surrounds the nucleus. The bulk of the comet's dust particles will miss the planet. But beginning 80 minutes after the comet zips by, there will be a roughly half-hour window during which something catastrophic is possible. Remotely possible.

"There's a small probability of an impact, but it's not zero," Zurek said. "And it only takes one to do you in."

JPL staffers pondered various ways to keep the spacecraft out of harm's way. The idea of using large communication antennae to BLOCK incoming dust particles was considered. They also looked at rotating the spacecraft so that the side with the least sensitive instruments would be facing the dust stream.

"There were more exotic mitigations we thought about," said Soren Madsen, who spent five years as chief engineer for NASA's Mars Exploration Program. "But they were ultimately not worth implementing."

Instead, ENGINEERS settled on another conflict-avoidance strategy: hiding.

"Mars will actually act as a shield for us," Madsen said. "Right behind Mars there will be a hole in the dust cloud."

The plan, he said, is to steer the orbiters into that "SAFE zone" for 30 to 40 minutes, until the worst of the threat has passed.

Satellites are in constant motion, so they can't simply park behind Mars. But ENGINEERS on Earth can adjust the speed of their orbits so that they will be flying on the opposite side of the planet when the risk is greatest.

On Tuesday, the Odyssey ORBITER will fire its engines for 5.5 seconds, giving it a gentle boost. It won't change the shape of its orbit, but it ensures it will be in the "safe zone" as the dust zips past.

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter performed a similar maneuver July 2 and has another planned for Aug. 27.

MAVEN already had a series of maneuvers planned for the weeks after it gets to Mars. At first, it will move around the planet in a long elliptical orbit, which will be trimmed down by a series of precisely timed engine firings. After Siding Spring's discovery, engineers tweaked those FLIGHT plans to make sure the spacecraft will be out of the way for the duration of the danger.

"These maneuvers are low-risk and low-cost," Madsen said.

It may sound like NASA scientists are being paranoid. But they're not the only ones. The European Space Agency had its Mars Express SATELLITE burn its engines June 23.

Now that NASA officials are reasonably certain that the spacecraft will be safe, they can focus on the OBSERVATIONS they will get to make during the unlikely encounter between planet and comet.

Using the instruments aboard the three orbiters, scientists plan to take a close look at the size and shape of Siding Spring's nucleus, and to figure out what gases are in its coma and its tail.

They also want to see how gas from the comet will interact with the Martian atmosphere. One hypothesis is that the comet will cause the gases in the upper atmosphere to heat up, causing them to escape into space. This could help researchers better understand why the air is so thin on Mars.

For Jared Espley, a co-investigator on the MAVEN mission, the cosmic coincidence is enough to make him giddy.

"This is an amazing, fantastic opportunity for science," he said. "It was a little unnerving at first, but now that we think we're SAFE, it's really exciting."

Quelle: Los Angeles Times

4437 Views