.

Noisy revolutions often emerge from quiet beginnings. So it was with the revolution of the Space Age. Forty five years ago today, a Saturn V rocket roared off from Cape Kennedy and carried the first humans to the moon; Buzz Aldrin and many others are marking the anniversary with live and virtual reminiscences (NASA has some information here, or you can find a lot using the #Apollo45 tag on Twitter). Lost in these worthy celebrations of Apollo 11′s achievement, though, is the simultaneous centennial of the much less tumultuous event that helped make it all possible.

.

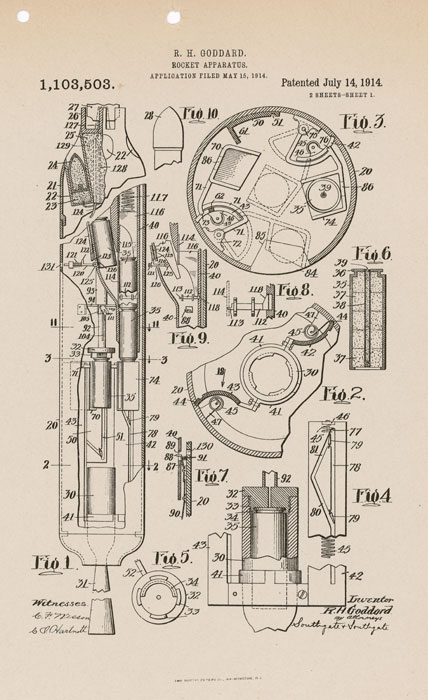

The drawing that launched a thousand ships: Goddard’s liquid-fueled rocket, patented July 14, 1914.

.

One hundred years ago this week, Robert H. Goddard received a pioneering patent for a liquid-fueled rocket–just like the one that took Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong, and Michael Collins to the moon. It was the one small step that led to one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.

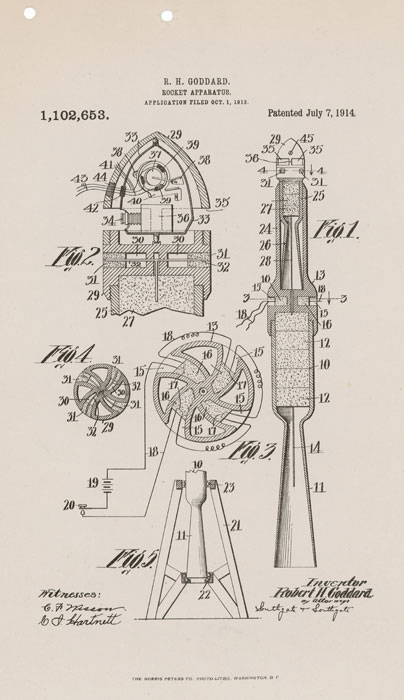

The patents marked a crucial turning point in the life of Goddard, as he transformed his early musings about rocketry and space exploration into concrete schemes. In 1913 he had come down with tuberculosis so severe that his doctors were unsure he would ever recover. He made the best of his long period of convalescence and, as his health slowly improved, drew up his first two rocketry patents. The first, for a multi-stage solid fuel rocket was granted on July 7, 1914. The second, for the liquid-fueled rocket, was approved a week later on July 14. (You can view the former patent here, and the landmark liquid-fuel rocket patent here.)

From there the advances kept getting bolder and louder. In 1915, Goddard began a series of landmark studies in rocketry, using gunpowder charges and experimenting with different types of nozzles to improve the amount of thrust. A year later he applied for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution, which agreed to provide $5,000 so that he could continue his explorations. That work culminated in his report, “A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes,” published by the Smithsonian press in 1920. The report focused on the technical aspects of his work, but included a provocative suggestion to send a rocket to the moon and detonate a bright explosive charge on arrival to prove that it had completed the journey.

.

Goddard’s very first patent, for a multi-stage rocket, July 7, 1914.

.

Goddard’s experiments captured the imagination of both like-minded engineers and the general public–both elements that were crucial to the birth of NASA and the intensifying sequence of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs that led to human footsteps on the moon. Not that it was all smooth sailing for Goddard. In a famously nasty 1920 editorial, The New York Times ridiculed his ideas about rocketry, declaring that his claim that a rocket could fly in the vacuum of space would “deny a fundamental law of dynamics, and only Dr. Einstein and his chosen dozen, so few and fit, are licensed to do that.”

(On July 17, 1969, as Apollo 11 was racing moonward, the Times published a gently self-mocking correction: “Further investigation and experimentation have confirmed the findings of Isaac Newton in the 17th Century and it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vacuum as well as in an atmosphere. The Times regrets the error.”)

The Times notwithstanding, Goddard’s work continued to earn great acclaim. His name is well remembered–not least in the naming of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. The photo of him posing with his first full-fledged liquid fueled rocket just before a test flight in 1926 is one of the iconic images of the early space age. His work also did not emerge in a vacuum, so to speak; some key predecessors, most notably Kinstantin Tsiolkovsky, had mapped out the idea of rocket travel in space. And yet it is easy to forget how the actual revolution began: not on a Florida launch pad, not with Sputnik, not with the German V-2 rockets, not even with a puff of smoke in Goddard’s lab.

The Space Age began quietly, a century ago, with a blueprint for the future.

Quelle: Discover

5506 Views