16.01.2026

The likelihood is that they will turn out to be radio frequency interference — but it's worth checking, scientists say.

David Anderson, co-creator of SETI@home, pictured in 2003. (Image credit: Robert Sanders/UC Berkeley.)

Astronomers are using China's powerful FAST radio telescope to chase after 100 intriguing signals detected by the SETI@home project, which is run by SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) scientists.

SETI@home, which ran from 1999 to 2020, had millions of users all around the world donating their CPU time to downloadable software that churned through data collected by the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico. In the end, 12 billion candidate narrowband signals were spotted. These signals appeared as "momentary blips of energy at a particular frequency coming from a particular point in the sky," David Anderson, a computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley and co-founder of the SETI@home project, said in a statement.

FAST, the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, has been patiently following up on this century of candidate extraterrestrial signals since July 2025. Although observations and analysis are still ongoing, bitter experience has taught the SETI@home team to expect them all to turn out to be local radio frequency interference (RFI) rather than real extraterrestrial beacons.

But whatever their origin, they represent the culmination of one of the largest citizen science projects ever undertaken. It's taken years to figure out how to properly scrutinize this vast amount of data.

"Until about 2016, we didn't really know what we were going to do with these detections that we'd accumulated," said Anderson. "We hadn't figured out how to do the whole second part of the analysis."

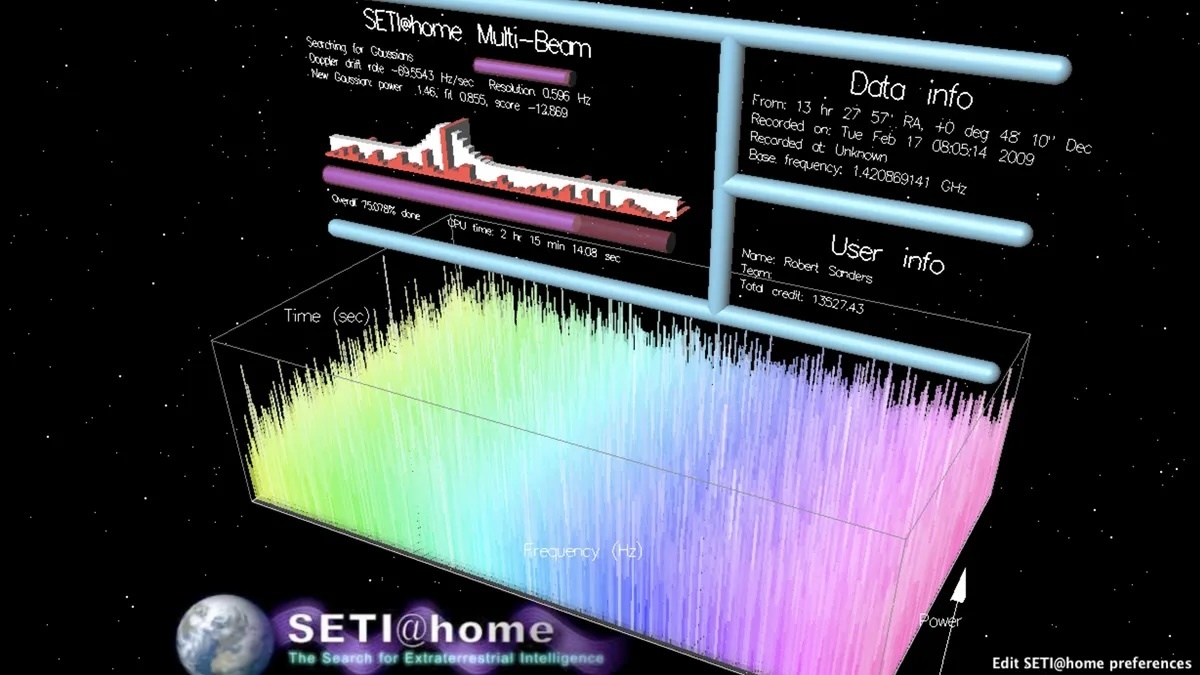

SETI@home found 12 billion narrowband radio signals, which have been whittled down to the final 100 for follow-up observations. (Image credit: Robert Sanders/UC Berkeley.

"There's no way that you can do a full investigation of every possible signal that you detect, because doing that still requires a person and eyeballs," added Berkeley astronomer Eric Korpela, who co-founded SETI@home along with Anderson and Dan Werthimer, who is an astronomer and electrical engineer also at Berkeley.

Eventually, at the supercomputer facilities of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Germany, algorithms designed to spot RFI sorted the wheat from the chaff, reducing those 12 billion to 1 million, then 1,000. These 1,000 signals then had to be inspected manually, by eye, before being whittled down to 100 that deserved a second look.

Arecibo had been the world's largest single-dish radio telescope, with a 305-meter aperture, until FAST came along in 2016. Because Arecibo collapsed and was destroyed in December 2020, FAST is now the only radio telescope capable of taking on these candidate signals.

"If we don't find ET, what we can say is that we have established a new sensitivity level. If there were a signal above a certain power, we would have found it," said Anderson.

The scale of the project has gone far beyond the dreams of Anderson or anyone on his team when SETI@home began in 1999. They thought they might get 50,000 users if they were lucky. By the end of the first week they had 200,000 users, and within a year they had 2 million.

'd say it went way, way beyond our initial expectations," said Anderson.

The data for SETI@home came from piggybacking on Arecibo's regular astronomical observations, and covered billions and billions of stars in the Milky Way.

"We are, without doubt, the most sensitive narrowband search of large portions of the sky, so we had the best chance of finding something," said Korpela. "So yeah, there's a little disappointment that we didn't see anything."

As the mammoth project nears its end, assuming no real extraterrestrial signals turn up in the final 100 candidates, Korpela looks back on the project not just with pride but as a learning experience for future SETI surveys.

"We have to do a better job of measuring what we're excluding," he said. "Are we throwing out the baby with the bath water? I don't think we know for most SETI searches and that is really a lesson for SETI searches everywhere. In a world where I had the money, I would reanalyze it the right way, meaning I'd fix the mistakes that we made. And we did make some mistakes. These were conscious choices because of how fast computers were in 1999."

Indeed, Korpela wonders whether one day a new project could be launched in the same vein as SETI@home to look over all the data again but with modern crowd-sourced computing power and machine learning in search of anything that was missed the first time around.

"There's still the potential that ET is in that data and we missed it just by a hair."

The overall results from SETI@home presented in two papers in 2025 in The Astronomical Journal: one paper on data analysis and findings, and another on data acquisition and processing.

Quelle: SC