8.01.2026

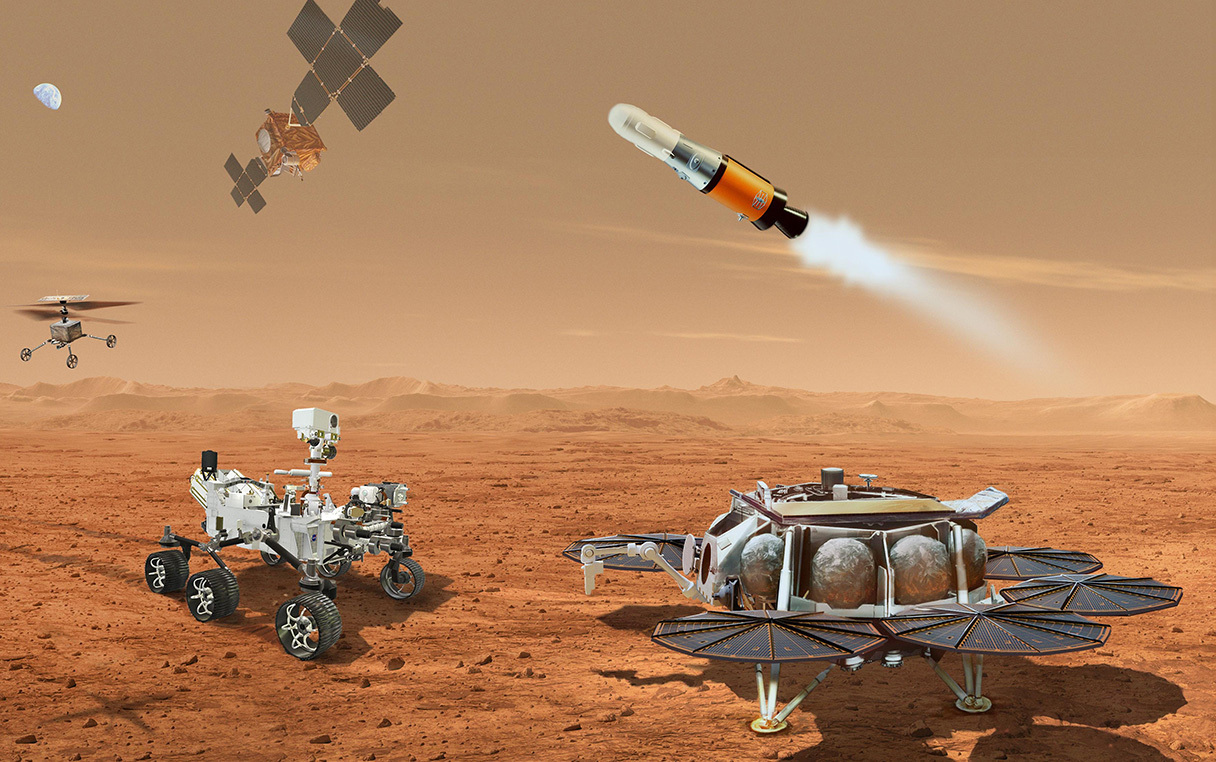

A suite of spacecraft—depicted in this artist’s representation—would have played a role in returning rock samples from Mars.NASA/ESA/JPL-CALTECH

After years on life support, NASA’s plan to collect martian rocks and ferry them back to Earth has died. Yesterday, Congress released a compromise spending bill for the present financial year that backs the White House’s effort to kill the Mars Sample Return (MSR) program. Although the bill must be passed by both congressional chambers and signed into law, it effectively signals the end of MSR.

The decision leaves in limbo planetary scientists’ top research objective and abandons, at least for now, several dozen rock cores collected by the Perseverance rover in anticipation that a future mission would rocket them into space. “This is deeply disappointing,” says Victoria Hamilton, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute and chair of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group. “When we’ve got memos coming out saying we want to be the dominant power in space, I wonder how we leave something this ambitious behind.”

At the same time, the demise of MSR could open up spending for planetary projects that have stalled at NASA, such as two missions already selected for Venus and the development of a probe to Uranus. Those hopes received a shot in the arm with the compromise spending bill, which would budget $7.25 billion for NASA science—a 1% cut from the previous year, but far more than the White House’s proposal to slash the agency’s science budget in half.

Amid its defense of NASA science, however, the text of the compromise bill was clear: “The agreement does not support the existing Mars Sample Return program.” Still, Congress did not cut the program entirely, shifting $110 million into a “Mars Future Missions” program meant to continue the development of technologies that MSR had been developing, including systems for landing spacecraft in the thin martian atmosphere. The money could allow NASA to hit the reset button on the program sometime in the future, says Jack Kiraly, director of government relations at the Planetary Society, an advocacy organization.

MSR had long pitted planetary scientists against each other, as fears grew that its ballooning cost—which rose to $11 billion in 2024—would consume far too much of NASA’s science budget. That led to repeated threats of cancellation from Congress, only for the program to survive in a more limited form while NASA reworked its plans. The agency’s final proposal for the mission, released in January 2025, would have brought its cost back down to $7 billion, closer to earlier estimates. But even that price tag was too high, with other NASA science missions struggling with cost overruns.

The failing U.S. commitment to returning the Perseverance samples has ramifications beyond the United States. MSR was meant to be a joint project with the European Space Agency (ESA), which would provide a spacecraft to catch a container holding the rock samples after it was rocketed off the martian surface. This “Earth Return Orbiter” would then carry the rocks back to our planet. ESA has already done much work on the spacecraft, and it indicated late last year that the project could now be reworked into a standalone mission to study martian geology from orbit. That could potentially add to MSR’s price tag if the mission was eventually revived, should the ESA craft no longer be available.

The faltering plans for MSR come as the scientific value of the rocks collected by Perseverance has grown. In 2024, the rover discovered what many researchers believe could be the best potential evidence for past life on the planet. Drilled out of a dry riverbed spilling into Jezero Crater, the ancient lake the rover has explored since its arrival in 2021, the Cheyava Falls sample contains mineral deposits called “leopard spots” that resemble traces typically left by microbes on Earth. But whether life created the features is impossible to say without getting the sample into labs on Earth. “A rock with a potential biosignature is awaiting return now, and other rocks hold breakthrough discoveries,” says Bethany Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Abandoning the effort would signal a loss of U.S. leadership, especially at a time when China is building its own sample-return program to Mars, says Philip Christensen, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University. “The science return from MSR [would] be exceptional and would provide the scientific and engineering foundation for sending humans to Mars.”

There are also pressing, practical questions about what NASA will do with the remaining time available to Perseverance, which is nearing 5 years of exploration and has nearly finished stocking its sample tubes, Hamilton says. “We’d really like to hear from NASA sooner than later that they will work with the community on a plan to get these samples.”

Quelle: AAAS