25.12.2025

After series of bleak findings, theory sparks hope for alternative energy source within Jupiter’s intriguing moon

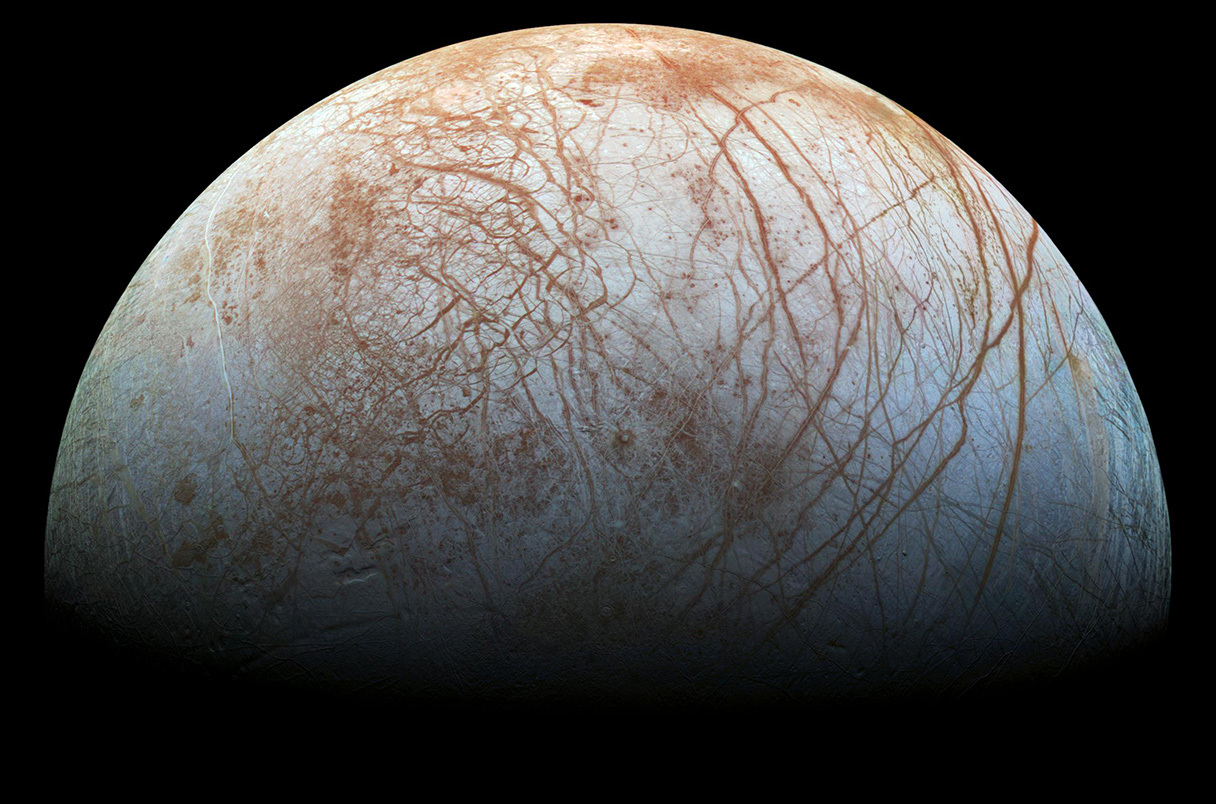

Europa’s icy crust covers a subsurface ocean. Radioactive decay could provide an energy source for submerged life

NEW ORLEANS—For decades, Jupiter’s moon Europa has tantalized astrobiologists: Its streaked, icy crust encapsulates a giant saltwater ocean—a perfect potential home for life. But recent headlines have dampened that enthusiasm. Its icy crust has turned out to be a shocking 35 kilometers thick—four Mount Everests—which implies in part that not much heat is coming out of Europa’s rocky interior. A moon with a weak pulse is less likely to host percolating hydrothermal vents, one potential home for life at the bottom of the ocean. Moreover, despite a claimed detection in 2013, nobody has confirmed the moon has geyserlike plumes of water spewing into space, which, if present, would support the idea of a geologically active world.

“Is Europa truly dead?” asks Ngoc Tuan Truong, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Or should we broaden our perspective on other mechanisms that can sustain life?”

Research Truong presented here last week at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union is putting a little pep back into Europa scientists’ step. He proposes that rocks leaching radioactive elements into the ocean could generate plenty of energy to support primordial life. What’s more, NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which launched last year, might be able to detect the breakdown of some of these elements when it arrives at the moon next decade for a series of ice-skimming flybys.

“It’s a novel idea,” says Kevin Trinh, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology. “It doesn’t rely on life having to exist near the sea floor, so it opens up other opportunities to sustain a biosphere.”

In previous models of potential life on Europa, researchers focused on the bottom of the moon’s subsurface ocean, where hot water in hydrothermal vents could react with rocks to generate hydrogen ions with energetic electrons that microbes could use as fuel. But if Europa’s interior is indeed colder and less active than once thought, these reactions would be limited in their ability to power life.

So, inspired by extreme habitats on Earth such as metal mines and deep-sea sediments, Truong hypothesized that Europa’s rocks themselves—and not the world’s internal heat—might hold the key. If radioactive elements leached out of Europa’s rocks and into its ocean over time, their natural decay would release heat, breaking apart water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen ions. Microbes could use the energy in these ions’ electrons for a “free lunch,” Truong says.

Truong and his colleagues modeled the concentrations of three radioactive isotopes in the oceans of Europa—uranium-235, uranium-238, and potassium-40—based on studies of the oceans of Europa, Enceladus, and Earth. All of these isotopes have also been discovered in meteorites. They then estimated how many ions their decays would spur, and whether those ions would provide enough energy to support life. “You can actually support quite a lot,” Truong says: at least 1 septillion cells, or the biomass of 1000 blue whales. And instead of being confined to deep sources of heat, Trinh notes, microbial life on Europa could theoretically live wherever the radioactive elements drift within the ocean.

The mechanism would be a useful energy source to add to standard water-rock interactions that yield electrons, says Steve Vance, an astrobiologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It’s also a long-lived one, because the half-life of potassium-40, for example, is 1.25 billion years. “Simply having radioactive materials available in any particular locale means you might have energy on site,” Vance says.

Regardless of how life on Europa might get its energy, the moon’s presumed lack of plate tectonics means its energy sources have probably dwindled over time, because there aren’t any fresh rocks to interact with the water—or fresh sources of radioactive elements, says Elizabeth Spiers, a planetary oceanographer and Europa specialist at the University of Texas at Austin. In addition, Europa’s ocean is twice as big as Earth’s, meaning any dissolved radioactive elements would be very dilute. Still, “Life is very efficient,” she says. “If there is energy, it is utilized.”

Truong’s hypothesis may soon be tested. The Juno spacecraft has already found potassium in Europa’s thin, gaseous atmosphere. Though the potassium-40 isotope is probably just a fraction of a percent of the element’s total mass at Europa, its decay produces argon-40, an element detectable by an instrument on board Clipper. If argon leaks through the ice or gets blasted out in geysers, the Clipper spacecraft could begin to search for it when it starts its flybys in 2031. A detection would quicken the pulse of astrobiologists and renew hopes that Europa hosts alien organisms. The alternative, Spiers says, is that Europa is “just a dead mudball out in the Solar System that has some fun ice designs.”

Quelle: AAAS