24.11.2025

Queen guitarist Sir Brian May's latest book explores the history, mystery and evolution of galaxies in a way never tried before – through 3D photography that takes years of painstaking work to create.

Many of us have looked at images of the galaxies around us and been overawed by the vastness of the Universe they hint at.

Seeing in 3D

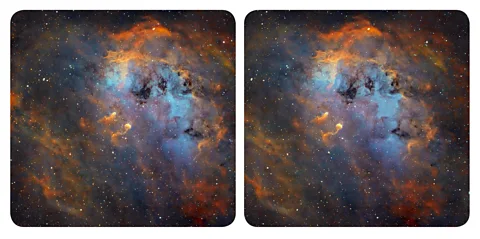

The images in this article are from Islands in Infinity: Galaxies 3D, and can be viewed in stereo with a special viewer.

If you happen to have a viewer at home, you can see the images in this story in 3D too. Hold the viewer in front of your eyes about 10-15cm (4-6in) from the screen. Don't squint; just relax your eyes. After a few moments the pictures should start to change.

Ever-more-powerful telescopes – including some floating in orbit – have allowed us to see further and further into the dark gulf of space, showing huge, far-off galaxies that were previously invisible to human eyes.

But as impressive as these images are, they can't convey the true scale. A two-dimensional image – no matter how impressive the device that took it – cannot show the breadth and depth of the billions of stars and cosmic gases contained in it.

That is, until now.

A trio of self-confessed astronomy nerds – Queen guitarist Sir Brian May, physicist Derek Ward-Thompson and astro-photographer J-P Metsavainio – set out to show what these galaxies might look like if you were somehow able to peer at them with eyes many, many light years apart.

Sir Brian is a long-standing devotee of stereo photography (which renders two almost identical images in three dimensions through a special viewing device) as well as a doctor of astrophysics (a degree he completed in 2007, decades after dropping his Imperial College London studies in favour of Queen.) He has produced several stereo photography books on space exploration and the mysteries of the cosmos through his publisher The London Stereoscopic Company.

Each of the books, such as Mission Moon 3D or Cosmic Clouds, has narrowed its focus on an aspect of space exploration or the cosmos surrounding us. But for this book, Islands in Infinity: Galaxies 3D, Sir Brian and his collaborators widened their lens, looking at the hundreds of millions of galaxies that we share the Universe with.

Sir Brian, alongside Ward-Thompson and Metsaivanio, launched the book at an event in London's Notting Hill in mid-November, presenting a lecture on some of the galaxies featured in the book and projecting some of Metsaivanio's three-dimensional images.

"We did a book called Cosmic Clouds, which was bringing the clouds of dust and gas in our own galaxy to life," Sir Brian tells the BBC ahead of the launch. "And that's not something anyone can do except J-P… having done that, where do we go next? Well, we go outside the galaxy, we go to other galaxies, we look at all galaxies in the Universe, and we engaged one of the world's foremost experts in galactic evolution, who's sitting right beside you."

War-Thompson says with a chuckle: "I wouldn't go quite that far, but I have been studying them for 40 years. I did point out that one of the galaxies in the book was my PhD thesis, and I've been looking at it for 40 years.

"Part of the beauty of the book is that I'm able to tell the story of how our knowledge has evolved in the course of those 40 years," continues Ward-Thompson, who lectures on physics and astrophysics at the University of Central Lancashire in Preston, in the north of England. "One example, when I was a student, we were taught that we lived in what we call a 'normal' spiral galaxy, just like you're imagining now, with the spiral arms coming out from the centre."

Ward-Thompson says we now know the Milky Way is a "barred spiral galaxy, with spiral arms starting from the ends of a central feature. "That we didn't know 40 years ago, and we only know because of the opening up of new wavelengths, space telescopes, infra-red satellites and so on."

The book shows some of the aethereal forms the galaxies we can observe take. Rendered in 3D by Metsaivanio's meticulous handiwork, they can be turned into 3D images by using the supplied Owl viewer, which was designed by Sir Brian. The images are not created with the help of AI – as the Finish artist and astrophotographer J-P Metsavainio explains later during his part of the lecture, they are made by creating a "copy" where each pixel is moved slightly so that when viewed through special glasses they form a 3D image.

Astronauts who took part in Nasa's Apollo Moon landings were taught a "cha cha" movement to take stereo pictures with a normal camera – taking one image and then moving the camera a few inches and taking another image from the same spot. Combined, these created a three-dimensional image.

But that technique doesn't work with space telescopes taking pictures of objects outside our Solar System, Sir Brian says. "There's no way you can 'cha cha' in space with any effect, so how can we possibly build a three-dimensional picture of a galaxy, without having your two viewpoints millions of light years apart. Well, J-P has his magic ways to create the parallax differences you would have if you were standing with our eyes thousands of light years apart. And it's a wonderful thing to see. We've never seen this before."

Metsaivanio has been taking photographs of the night skies for 30 years, and around 25 years ago started converting them to three-dimensional images "just for personal joy", he says. Each of the images he creates has to be cross referenced with the available scientific knowledge. "I have so much information, and sources for information like this one here [pointing to Ward-Thompson]. So my models are becoming more and more accurate."

Some of his images have required him to remove closer stars or galaxies to get a clearer view of the required subjects; what might look like a pinprick on the page could be a giant supernova or a cluster of stars, closer to our view than the subject. Our Milky Way galaxy is full of such astronomical "clutter" that needs to be carefully removed to show the featured galaxy in its full glory.

"I'm a star destroyer – and a lot of planets, probably – when I remove all the stars from our Milky Way," says Metsaivanio. "When you look at the picture of the Andromeda, what you will see here in 3D is with the stars from the Milky Way," he says, motioning towards the screen set up for the night's projection. "When I remove them, you see the Andromeda, as you [would] see it outside of the Milky Way. And then this make you realise that those stars that were in front of the picture. I removed them. There is nothing between us and Andromeda and emptiness for 2.5 million light years. That's mind-blowing."

What's also mind-blowing is the amount of work that has to go into his creations; during one unveiling later that night of an image of the Milky Way, he admits that the finished image took him 12 years of work to complete, including more than 1,200 different exposures.

The book was written by Ward-Thompson and edited by Sir Brian, explaining the evolution of the galaxies we can now see in deep space. The galaxies shown are as colourful and varied as microscopic life on a lab slide; NGC 253 gleams in blue and gold like an antique pendant; NGC 3925 has rings like that of a disturbed pond, the waves created perhaps by a smaller galaxy colliding with it and causing a "splash". One image shows two galaxies, NGC 4567 and 4568, in the process of colliding, crashing into each other in what Ward-Thompson has called a "train wreck of the cosmos".

Quelle: BBC