4.10.2025

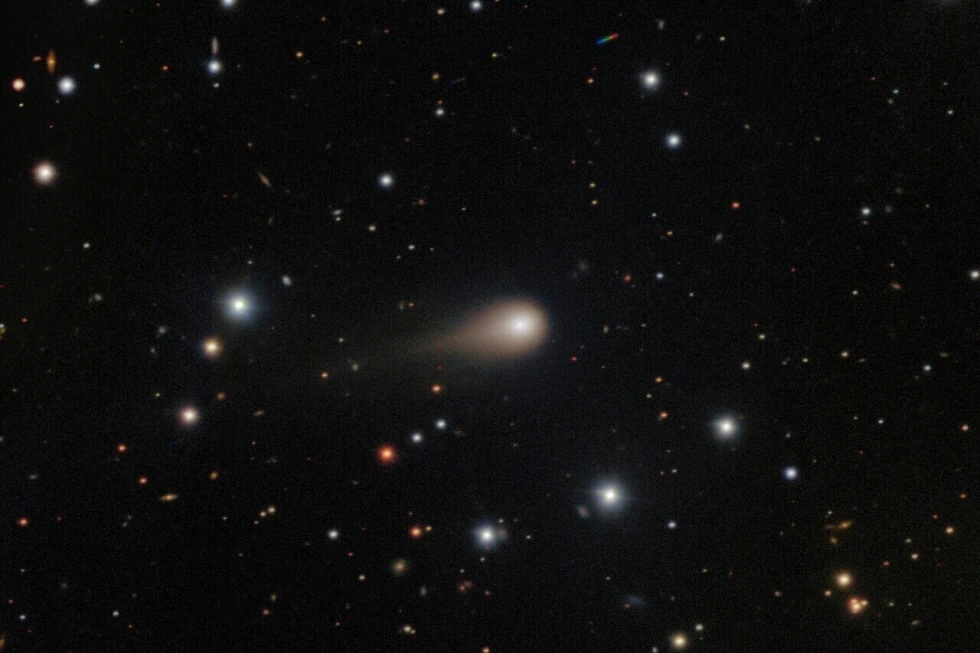

This image composed from multiple exposures and provided by NSF’s NOIRLab shows a comet streaking across a star field above the International Gemini Observatory on Cerro Pachon, near La Serena, Chile

CAPE CANAVERAL, — A comet from another star system will swing by Mars on Friday as a fleet of spacecraft trains its sights on the interstellar visitor.

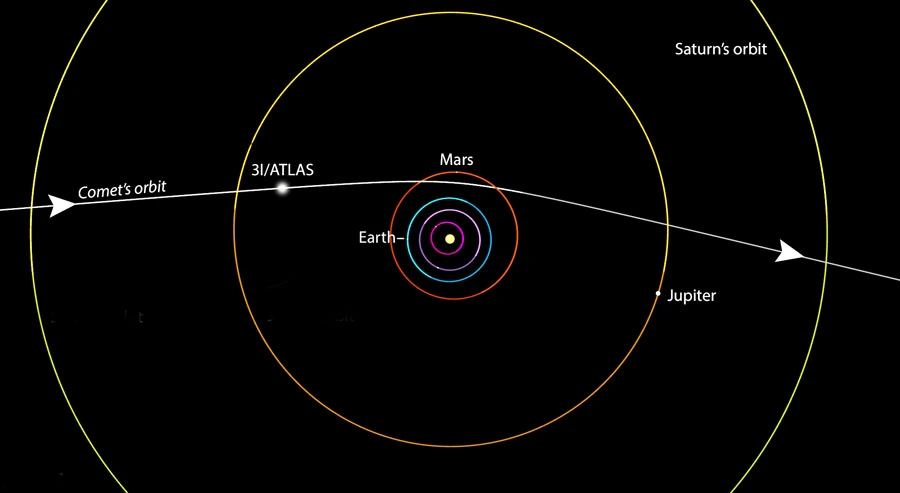

The comet known as 3I/Atlas will hurtle within 18 million miles (29 million kilometers) of the red planet, its closest approach during its trek through the inner solar system. Its breakneck speed: 193,000 mph (310,000 kph).

Both of the European Space Agency’s satellites around Mars are already aiming their cameras at the comet, which is only the third interstellar object known to have passed our way. NASA’s satellite and rovers at the red planet are also available to assist in the observations.

Discovered in July, the comet poses no threat to Earth or its neighboring planets. It will come closest to the sun at the end of October. Throughout November, ESA’s Juice spacecraft, which is headed to Jupiter and its icy moons, will keep an eye on the comet.

The comet will make its closest approach to Earth in December, passing within 167 million miles (269 million kilometers).

Observations by the Hubble Space Telescope put the comet’s nucleus at no more than 3.5 miles (5.6 kilometers) across. It could be as small as 1,444 feet (440 meters), according to NASA.

Quelle: AP

+++

MARS ORBITERS WILL HAVE FRONT-ROW SEATS TO INTERSTELLAR COMET

EUROPEAN AND NASA ORBITERS AWAIT THE COMET

“We are going to try to get images,” confirms Colin Wilson, the European Space Agency (ESA) project scientist for both the Mars Express and ExoMars Trace Gas orbiters. Although the resolution of the two spacecraft’s cameras has no chance of resolving the nucleus, there’s hope for resolving the coma of gases and dust surrounding the central object. That coma may extend a few tens of thousand kilometers across, Wilson says, adding, “We would hope to get maybe several tens of pixels across that.”

Mars Express, Wilson says, will be using the Super Resolution Channel on its High-Resolution Stereo Camera, which is monochromatic. With ExoMars, they will be using the Color and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CASSIS) telescope, which has a 13.5-centimeter primary mirror and four CCDs with different color filters. Both spacecraft carry spectrometers that take in from near-infrared to ultraviolet light. But Wilson cautions, “We don’t know if we’ll get enough signal.”

“So, we are hoping for at least some imagery, and then if we get any spectra, that would be a bonus,” he says. “We are not promising anything other than a monochromatic image.”

JPL HORIZONS with additions by Bob King

Meanwhile, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) will also be taking images, with observations already planned and proceeding despite the U.S. federal government shutdown. The team will use MRO’s High Resolution Imaging Experiment (HIRISE) camera, which has a half-meter mirror and 14 detectors that cover from visible into near-infrared wavelengths.

The principal investigator of the HIRISE camera, Alfred McEwen (University of Arizona), tells Sky & Telescope that his team has to plan carefully on how to take these images. The comet’s brightness isn’t exactly known; if it’s faint and they use too short of an exposure time, they won’t pick it up. But if it’s bright, they run the risk of an overexposed image. To hedge their bets, the team is planning for two different exposure times across four images.

Because of its large mirror and its proximity to the comet, Marshall Eubanks (Space Initiatives) says, “I think MRO is going to be competitive with anything we do from Earth.” Eubanks adds that the comet appears to be passing through a twisted part of the Sun’s magnetic field, which extends all the way out to the Red Planet. That field might create ripples in the comet’s tail, which MRO might detect.

OPERATION: COMET TAKEOVER

Unlike the operation of Mars rovers, whose explorations are planned on a daily basis because of ever-changing surface conditions, planning for the European orbiters is normally carried out at least three months in advance. As it happens, the planning October options ocurred in July — just when 3I/ATLAS was discovered.

“There was a very rapid turnaround to ask the teams if they would be able to observe it,” Wilson says. “We had a draft plan already, and then we moved a few things around so that we could prioritize these observations.”