30.09.2025

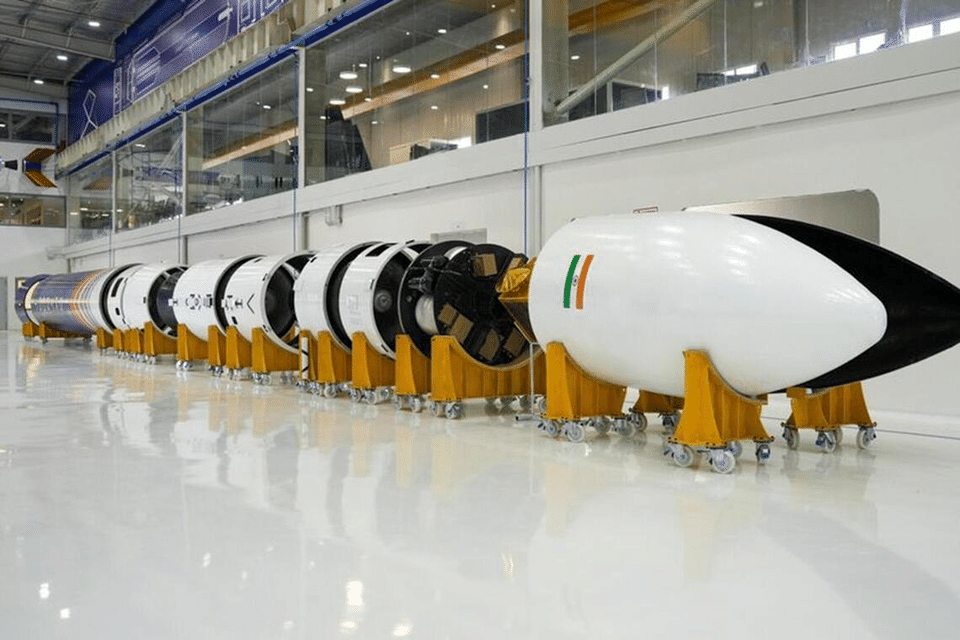

Skyroot Aerospace's rocket being developed in their facility in the southern city of Hyderabad.

PHOTO: SKYROOT AEROSPACE

- Skyroot Aerospace aims to be India's first private orbital launch with its Vikram-1 rocket, carrying domestic and foreign satellites. Singapore could be a future customer.

- India and Singapore signed a space cooperation agreement in September 2025, covering joint work on policy, industry promotion, and research and development.

- India's private space sector faces challenges like workforce shortages and supply chain issues but aims to grow to a US$44 billion economy by 2033.

NEW DELHI – In a high-tech building in the southern Indian city of Hyderabad, engineers at Indian space firm Skyroot Aerospace are working tirelessly on a rocket, made of carbon fibre and powered by a 3D-printed engine, that could end up being the country’s first orbital launch by a private company.

The rocket is named Vikram 1 after Dr Vikram Sarabhai, who is considered the father of India’s space programme, and will carry a mix of domestic and foreign satellites. The launch date has not been made public.

If all goes according to plan, the launch will mark the beginning of a new era for India’s space programme, which has long been the preserve of the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro), and could also kick-start a new wave of cooperation with Singapore.

Skyroot Aerospace, which has raised around US$95.5 million (S$123 million) since it was founded in 2018, is backed by weighty investors, including Singapore’s GIC and Temasek.

And Singapore, sources said, could become one of Skyroot Aerospace’s customers, with discussions under way to launch a Singaporean satellite on a future mission.

India has already launched more than 20 Singapore-made satellites over the past two decades through Isro.

But with New Delhi expanding the role of private players in India’s space sector in 2020, Singapore now sees opportunities to also work with a fast-emerging group of private companies that are supported by Isro.

“Working with Singapore will be beneficial for India too,” said Dr Pawan Goenka, chairman of the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe), the country’s space regulator, in an interview with The Straits Times.

“India is fairly advanced in space technology and we want to be the regional integrator of all things space.”

Singapore joins India’s space race

For Singapore, which set up its first satellite ground station on Sentosa in 1971 and launched its first communications satellite in 1998, the collaboration with India is replete with promise as it seeks to develop its own space industry.

India’s space programme is known for its frugality. Isro’s Mars mission in 2014 cost just around US$74 million, less than the budget of the 2013 Hollywood film Gravity. Its

2023 Chandrayaan-3 moon landing

cost an estimated US$75 million.

That proven track record, which India’s private sector hopes to emulate, is appealing to the city-state as it seeks to widen the use of space technologies in areas such as weather forecasting.

India and Singapore signed

a wide-ranging space cooperation agreement

during the early September 2025 visit of Prime Minister Lawrence Wong to New Delhi.

The memorandum of understanding, underlining the level of trust built up over decades of close cooperation, inked between IN-SPACe and Singapore’s Office for Space Technology & Industry (OSTIn), covers joint work on space policy and law, industry promotion and research and development.

“These areas of collaboration align with Singapore’s interests in applying space technologies across key sectors, including aviation, maritime, info-communications and sustainability,” an OSTIn spokesman told ST.

The agreement will build on past space collaborations.

Among the more than 20 Singaporean satellites lofted into space is the 2023 launch of DS-SAR, a 352kg info-communications radar-imaging satellite developed by Singapore’s Defence Science and Technology Agency and ST Engineering.

Universities such as Nanyang Technological University have also sent payloads into space aboard Indian rockets.

In 2024, space technology company Dhruva Space partnered Singapore space semiconductor company Zero-Error Systems to integrate cutting-edge semiconductor technology into Dhruva Space’s OBC (on-board computer) sub-system, a critical component responsible for managing satellite operations and payload controls, said a press statement from Dhruva Space.

With Singapore’s gaze on it, the stakes are high for Skyroot Aerospace.

Mr Pawan Kumar Chandana, Skyroot’s co-founder, chief executive and a former Isro scientist, told ST he had received inquiries from Singapore, but was surprised that other foreign customers were also ready to take a “leap of faith” on a maiden launch.

“We have some customers who took that leap of faith, and they ended up putting the satellite along with us for the first launch,” said Mr Chandana, adding that the launch date and number of satellites would be announced at a later date.

“It’s a learning curve. We will focus on the first three launches. Actually, very few companies are able to consistently get success in the (first) three launches.”

Since 2018, the start-up has grown from a dozen employees to over 500, and it hopes to offer the kind of low-cost access to orbit that has become a hallmark of India’s space programme.

In August 2025, the start-up cleared a critical hurdle by conducting a successful ground test of its rocket motor.

This followed its breakthrough in 2022, when it became the first Indian private firm to carry out a suborbital launch.

“It (Skyroot’s launch) will be a very big milestone because that will be the first orbital launch. So, this will be the first time an (Indian) private sector-designed launch vehicle will leave Earth’s gravity and go into space,” said IN-SPACe’s Dr Goenka.

Apart from Skyroot Aerospace, another Indian start-up, Agnikul Cosmos, has also successfully completed a suborbital test of its launch vehicle and is also moving towards an orbital launch perhaps by 2026, said Dr Goenka.

The new space players

About three dozen private firms operated as suppliers to Isro before India opened its space sector to private players five years ago.

Today, that number has swelled to about 350 start-ups, many of which are building satellites, rockets or space-based applications, albeit with full cooperation from Isro, which is providing everything from technical know-how to its testing facilities and launch pads.

This means India’s private sector does not have to start from scratch, much like how the National Aeronautics and Space Administration helped to develop the United States’ private sector. The evolution of the US space programme saw the emergence of SpaceX, which India hopes to emulate.

After opening space to the private sector, the government brought in policy reforms, including allowing foreign direct investment of between 49 per cent and 100 per cent, depending on the sensitivity of the area, and setting up IN-SPACe to regulate and promote the sector.

Skyroot Aerospace's rocket being developed in their facility in the southern city of Hyderabad.

PHOTO: SKYROOT AEROSPACE

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a champion of India’s space efforts, has urged private companies to step forward to scale rocket launches from the current five to six a year to 50 and create five unicorn companies in the next five years.

The government has set a target of growing the country’s space economy from US$8.4 billion in 2022 to US$44 billion by 2033. Isro, meanwhile, is pressing ahead with plans for its first crewed mission in 2027 and a space station by 2035, in addition to continuing with satellite launches.

A key goal for the government is to attract small and nano-satellite launches to India, with a dedicated launchpad for Small Satellite Launch Vehicles being built at Kulasekarapattinam in Tamil Nadu’s Thoothukudi district, which is set to be ready by December 2026.

Signalling that India’s private sector has the full support of the government, a consortium led by Bengaluru-based space technology company Pixxel was selected by IN-SPACe in August 2025 to design, build, own and operate a 12-satellite constellation for climate monitoring, disaster management and national security over the next four to five years with an investment of over 12 billion rupees (S$176 million). This is under a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) framework.

State-owned aerospace giant Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) has also been awarded the rights to manufacture and market Isro’s Small Satellite Launch Vehicle – a first-of-its-kind technology transfer deal.

“Start-ups are doing things not attempted by Isro,” said Dr Goenka. “They are working on electric propulsion, semi-cryogenic engines, fully printed 3D-engines, and very high-end cameras for earth observation. Together, all of these developments are making the private sector bigger and bigger in space.”

Obstacles on the horizon

But India’s private space race is not without its challenges. To compete globally, start-ups have to deliver on the technology before even focusing on providing cost-efficient services.

“The first thing for the private sector is that in terms of technology, they have to be up among the leaders. Otherwise, nobody will want to come to India to buy that. But having done that, they can offer frugality and capacity,” said Dr Goenka.

Workforce shortages also plague the sector. India produces over 1.5 million engineers a year, but private companies are finding it tough to find engineers with the required skills for the space industry.

Supply chains are also struggling to keep pace with demand, said Mr Awais Ahmed, chief executive and founder of Pixxel.

“What’s needed now is fast and focused execution. Plug-and-play infrastructure, dedicated subsidies for space-tech start-ups, faster clearances and greater investment in workforce development can create the conditions for globally competitive space companies to emerge from India,” he said.

He added that while IN-SPACe and Isro have made encouraging strides,“there’s still a gap in ease of doing business regarding manufacturing, licensing and timelines that match private sector velocity”.

To plug some of these gaps, some Indian states have announced dedicated space policies, offering incentives such as cheaper land or tax cuts and subsidies, to position themselves to attract space firms.

Skyroot Aerospace's rocket being developed in their facility in the southern city of Hyderabad.

PHOTO: SKYROOT AEROSPACE

Gujarat is building a space manufacturing park and a skills hub, Tamil Nadu is looking at dedicated space bays or space industry hubs, and Andhra Pradesh has announced plans for space cities, including in Tirupati, which houses a temple that is a major Hindu pilgrimage site.

Retired lieutenant-general A.K. Bhatt, the director-general of the Indian Space Association, a non-profit body that promotes the private space industry in India, said the competition among the states mirrored strategies seen in China and Australia, and reflected the growing search for “India’s Elon Musk”.

“States are now evangelising or supporting or pushing for the space sector to go (forward),” said Mr Bhatt.

The everyday impact of space

While launches grab headlines, Singapore would also be likely watching the many Indian start-ups that are focused on how space can improve daily life after the satellites are operating in space. Of the 350 companies active in the sector, a large share is working on applications using satellite data in navigation, climate resilience, agriculture and defence.

One such firm is Suhora Technologies, a geospatial intelligence company that delivers high-resolution satellite data for defence, disaster management, insurance and environmental monitoring.

“If we can help a city prepare for a cyclone a few hours earlier or guide a state’s agricultural strategy with accurate land insights, then we’ve done our job,” said Suhora CEO and co-founder Krishanu Acharya. It is investing in multi-sensor fusion and artificial intelligence-driven analytics, combining thermal and hyperspectral data to provide deeper insights.

“Space is no longer about distant science,” he added. “It’s becoming a critical part of how we understand the world.”

From carrying rocket parts on bicycles in the 1960s to launching a moon mission for just US$75 million in 2024, India’s space journey has long been a story dotted with not just frugality but also ingenuity.

Now, as companies like Skyroot Aerospace, Dhruva, Pixxel and Suhora prepare to break new ground, the next chapter will test whether India’s private sector can scale those successes into a globally competitive industry.

“So the technology capability is there in India. But brains alone cannot make you conquer space. You need investment. This is where India is at this point,” said Mr Bhatt, underlining the need for continued investment going forward.

“Isro as a research organisation was not commercially backed. They were looking at more exploratory science. But now space has become an opportunity for business. That is why the private sector is important.”

Quelle: THE STRAITS TIMES