9.09.2025

Using data from NASA’s now-retired Dawn spacecraft, scientists have found that Ceres, a dwarf planet and the largest object in the asteroid belt, may have once had a lasting source of chemical energy. The Dawn data revealed evidence of molecules needed to fuel microbial metabolisms on Ceres.

While the finding doesn’t confirm that microorganisms existed on Ceres long ago, it does support theories that the dwarf planet may have once been capable of supporting single-celled lifeforms.

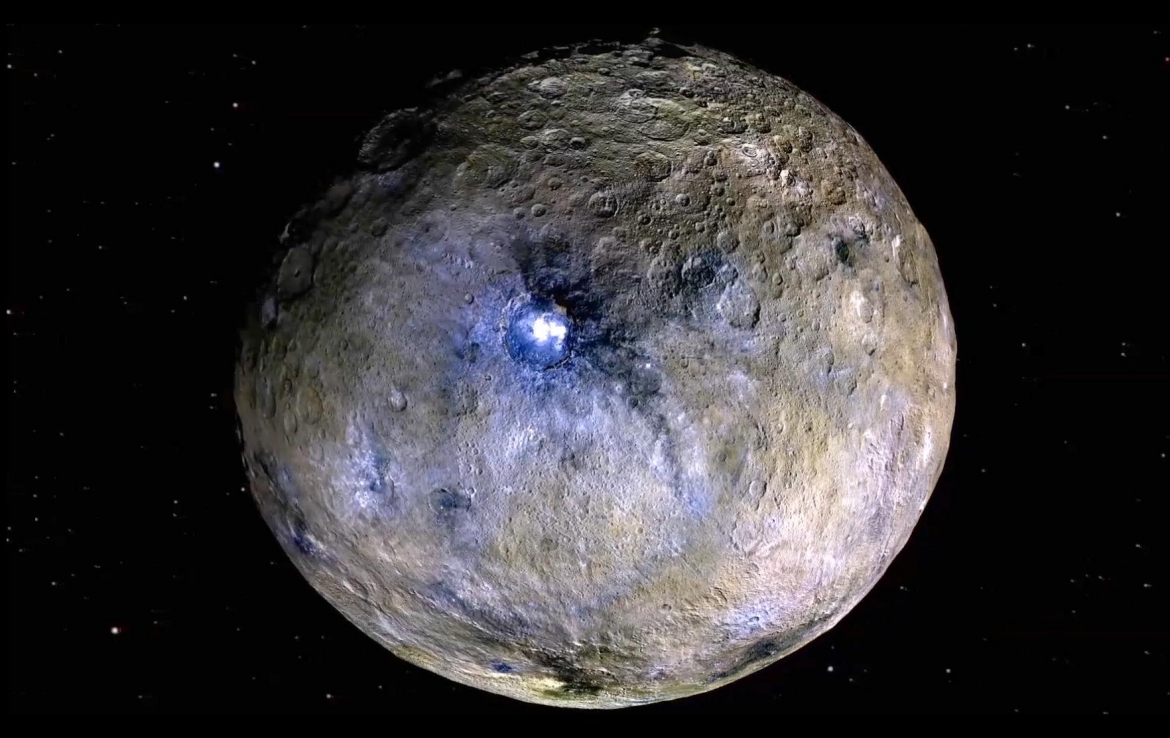

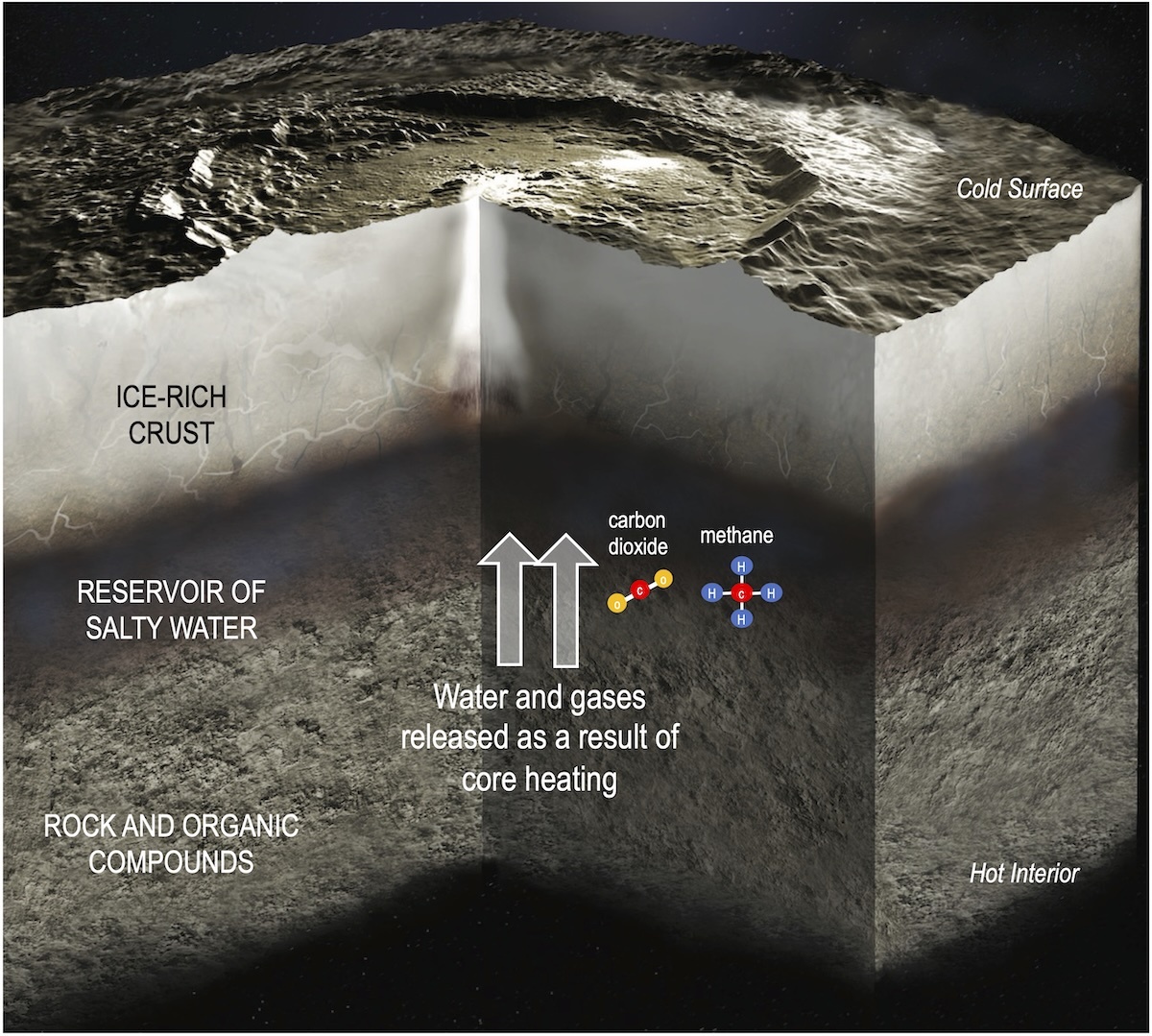

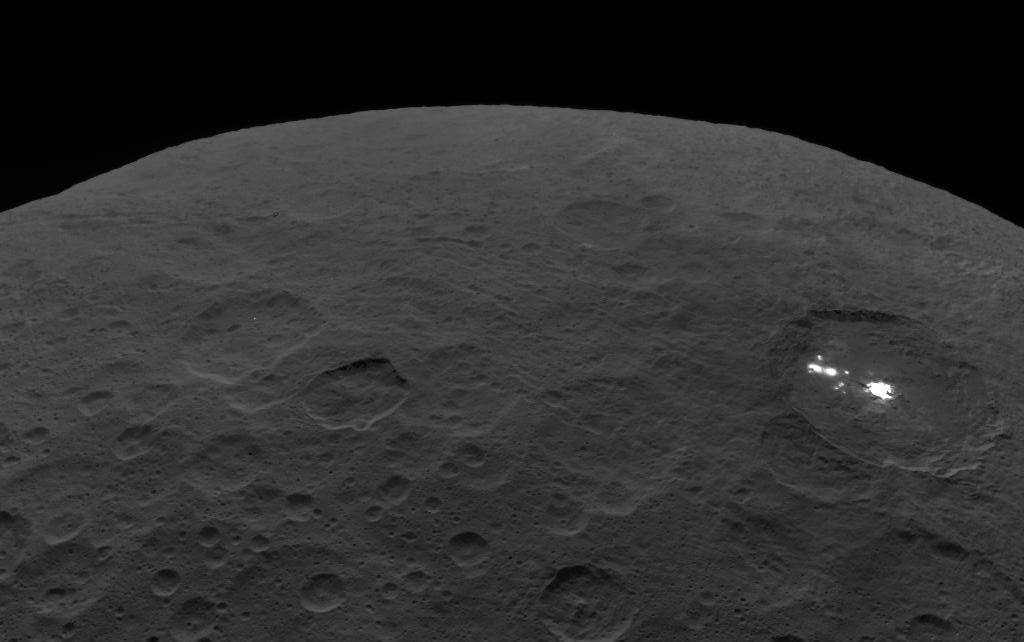

Examining pictures of Ceres, areas of bright, reflective material can be seen on the dwarf planet’s cratered surface. Dawn previously revealed that these regions are comprised of salts left by liquid that percolated up to the surface from an underground brine reservoir. Other research from Dawn revealed evidence of organic material, specifically carbon molecules, on Ceres, which are required to support the existence of microbial cells.

Evaluating a planet’s habitability is a complex process, especially on a cold and dormant planet like Ceres; however, the existence of water and carbon molecules is crucial for the potential existence of life. Another critical component of habitability is a source of “food,” and the new findings show that a continuous source of chemical energy may have existed in Ceres’ ancient past.

In the new study, led by Samuel Courville of Arizona State University and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, thermal and chemical models were developed to simulate the temperature and interior composition of Ceres over extended periods. The team found that, around 2.5 billion years ago, a steady stream of hot water in a subsurface ocean would have transported dissolved gases up from metamorphosed rocks in the dwarf planet’s rocky core. The stream would have been heated from the radioactive decay of elements within Ceres’ young rocky interior. Interestingly, this process is fairly common on other planets in the solar system.

“On Earth, when hot water from deep underground mixes with the ocean, the result is often a buffet for microbes — a feast of chemical energy. So it could have big implications if we could determine whether Ceres’ ocean had an influx of hydrothermal fluid in the past,” Courville said.

While recent studies on Ceres’ habitability have revealed promising results, the dwarf planet is unlikely to be a hospitable place for life today. The dwarf planet is cooler and now features more ice than water. Radioactive decay within Ceres’ interior has slowed, reducing the amount of heat available to water and causing any liquids to become a concentrated brine.

If Ceres ever hosted life, it would have been approximately 2.5 to 4 billion years ago, when the rocky core reached its maximum temperature. During that time, warm fluids would have filled Ceres’ subsurface water reservoirs, creating environments rich with nutrients and molecules needed for life.

Furthermore, Ceres’ lack of a natural satellite or parent planet means that the dwarf planet can’t benefit from internal heating generated by the gravitational push and pull between two planetary bodies. Thus, scientists believe that Ceres’ greatest chances of habitability are long past.

Though Ceres is the innermost of the dwarf planets, Courville et al.’s findings apply to many other dwarf planets in the outer reaches of our solar system. Many dwarf planets also lack satellites or parent planets, resulting in a lack of internal heating and a period of habitability that occurred billions of years ago

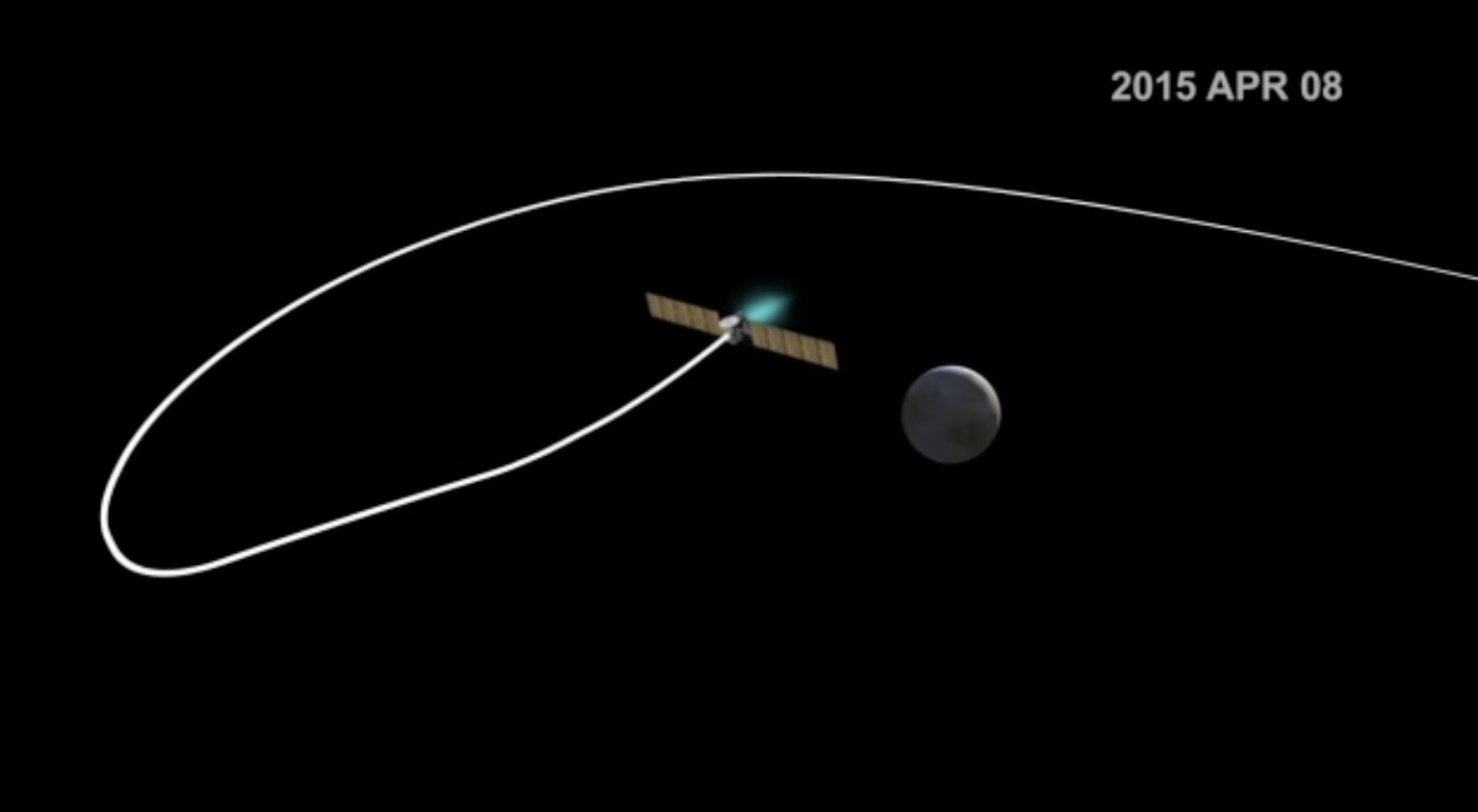

NASA’s Dawn mission launched in September 2007 and visited the asteroid Vesta before entering orbit around Ceres in March 2015. While at Ceres, Dawn extensively imaged and mapped the dwarf planet’s surface in both visible and infrared wavelengths. After completing a one-year mission extension from 2016 to 2017, Dawn was placed in an uncontrolled orbit and ran out of propellant on Oct. 31, 2018. The dormant spacecraft continues to orbit Ceres today.

Quelle: NSF