11.06.2025

Degrading LIGO’s observations of gravitational waves would amount to “killing a newborn baby,” one astrophysicist says

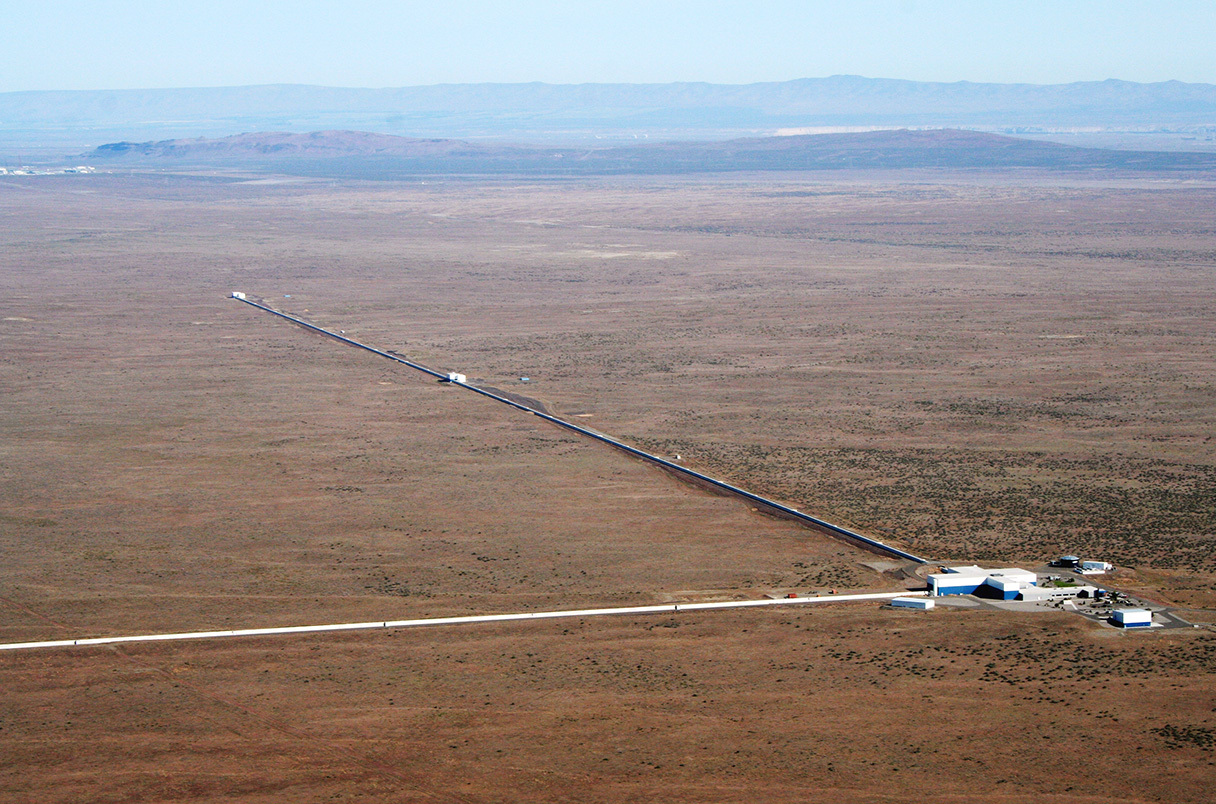

A passing gravitational wave typically stretches the 4-kilometer-long arms of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory detector in Hanford, Washington, (above) by about 0.0000000000000000001%.CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY; MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY; LASER INTERFEROMETER GRAVITATIONAL-WAVE OBSERVATORY LAB

Just 10 years ago, 900 scientists working with two of the biggest and most sensitive scientific devices ever built made a discovery that opened new eyes on the universe. The twin detectors of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) spotted ripples in space itself set off when two massive black holes 1.3 billion light-years away spiraled into each other. For the first time, humans had detected an astrophysical object with something besides electromagnetic radiation. It was a dramatic demonstration of general relativity, Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity, and it marked the birth of a new field, gravitational wave astronomy.

Now, however, a budget-cutting plan by the administration of President Donald Trump would close one of the two LIGO interferometers, enormous L-shaped optical instrumentsin which light bounces between mirrors in arms 4 kilometers long. The move would save roughly $20 million while drastically cutting LIGO’s ability to identify and localize the cataclysmic celestial events that produce gravitational waves. Physicists say it would largely eliminate the field LIGO birthed. “You’re killing a newborn baby,” warns Gianluca Gemme, an astrophysicist with Italy’s National Institute for Nuclear Physics and spokesperson for Virgo, a smaller gravitational wave detector near Pisa.

Three early leaders of the LIGO effort won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics for the first detection of a gravitational wave. The LIGO detectors in Louisiana and Washington state, working together with the less sensitive Virgo, have now captured signals from more than 300 sources, almost all black hole mergers. And all the detectors continue to gain sensitivity through upgrades, says David Reitze, a physicist at the California Institute of Technology and director of LIGO. “We’re at the tip of the iceberg in terms of the amount of science we can do.”

However, in its proposed budget for 2026, the Trump administration would slash the National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) $9 billion budget by 57%, and, as part that cut, trim LIGO’s annual operating budget from $48 million to $29 million. The proposed budget explicitly calls for eliminating one of LIGO’s interferometers, but doesn’t specify which one. In a two-sentence email to Science, an NSF spokesperson said the plan reflects “a strategic alignment of resources in a constrained fiscal environment.”

The loss would inflict disproportionate damage on the observatory’s scientific reach, scientists say. Researchers would find it more difficult to distinguish a black hole collision in the distant cosmos from a nearby seismic tremor or anything else that shakes the remaining interferometer. A real gravitational wave likely produces signals in both U.S. detectors within 10 milliseconds, the time it takes the ripple to cover the cross-country distance. Without the ability to compare data from the two instruments, detections would be less sure and their rate would fall at least 25%, Reitze says, and possibly much more.

With a single detector LIGO would also lose the ability to roughly locate the source of a signal on the sky—the key to its working as an observatory. LIGO showed the power of source localization in 2017 when it, working with Virgo, detected two neutron stars spiraling into each other. Around the globe and in space, myriad telescopes across the electromagnetic spectrum wheeled to see the dramatic explosion that ensued, a so-called kilonova that produced a gamma ray burst and spewed gold and other newly formed elements. Having more than one LIGO detector made that possible, says Roger Blandford, a theoretical astrophysicist at Stanford University. “There’s a reason they built two of them.”

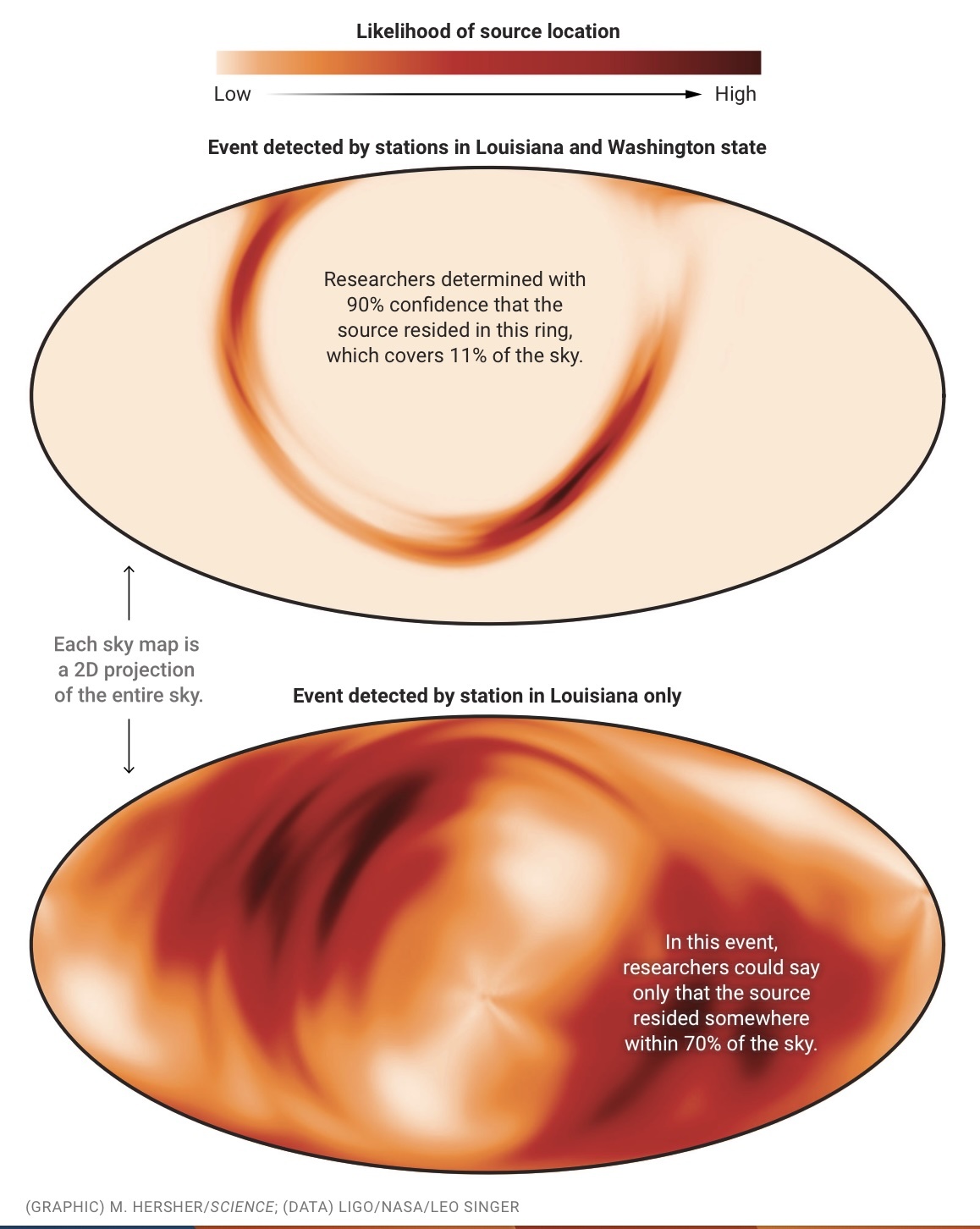

To locate a source, researchers use the arrival time of the signals at different detectors to triangulate. If Virgo and the two LIGO detectors all see a signal, they can now locate its source to as little as 5 square degrees. The two LIGO detectors can also locate a source to a reasonably small circle on the sky. But a single LIGO detector can do little better than half the sky, Reitze says. “Astronomers look at that and go, ‘Why did you even wake us up?’”

Closing a LIGO interferometer would also likely mean cutting scientific staff, a prospect that worries some people more than anything else. “There’s a whole culture there that has worked together to build these two magnificent facilities,” Blandford says, “and you don’t re-create this just by hiring some people in an ad.” Gabriela Gonzalez, a physicist and LIGO member at Louisiana State University, notes that the majority of graduate students who work on LIGO go on to jobs in high-tech industries. “It’s not just the science results, it’s the people we train that will be lost.”

It takes two

These sky maps show real data from two recent Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory events, one that registered a signal in both of the observatory’s stations and one that produced a signal in only one of them. The comparison shows how triggering both detectors helps researchers locate the source of the gravitational waves.

France Córdova, an astrophysicist who served as NSF director from 2014 to 2020, says the proposed lopping of LIGO in half may be, oddly, a testament to the prestige of the project even in the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). “Somebody in OMB understands that this was significant enough not to cancel it altogether, but didn’t understand the science” well enough to know why it couldn’t be cut in half, she speculates.

Physicists are still hopeful the proposed closure isn’t set in stone. “We’re having discussions with NSF to understand better where it came from and what it really means,” Reitze says. “Is it binding language or is there some latitude?” Gonzalez notes that Congress sets the agency’s final budget. “Legislators are smart,” she says. “I know that they are in difficult positions, and they do a very difficult job, but they listen to people, and we are talking to them.”

Quelle: AAAS