18.04.2025

Artwork of K2-18b, a faraway world that may be home to life

Scientists have found new but tentative evidence that a faraway world orbiting another star may be home to life.

A Cambridge team studying the atmosphere of a planet called K2-18b has detected signs of molecules which on Earth are only produced by simple organisms.

This is the second, and more promising, time chemicals associated with life have been detected in the planet's atmosphere by Nasa's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

But the team and independent astronomers stress that more data is needed to confirm these results.

The lead researcher, Prof Nikku Madhusudhan, told me at his lab at Cambridge University's Institute of Astronomy that he hopes to obtain the clinching evidence soon.

"This is the strongest evidence yet there is possibly life out there. I can realistically say that we can confirm this signal within one to two years."

K2-18b is two-and-a-half times the size of Earth and is 700 trillion miles, or 124 light years, away from us - a distance far beyond what any human could travel in a lifetime.

JWST is so powerful that it can analyse the chemical composition of the planet's atmosphere from the light that passes through from the small red Sun it orbits.

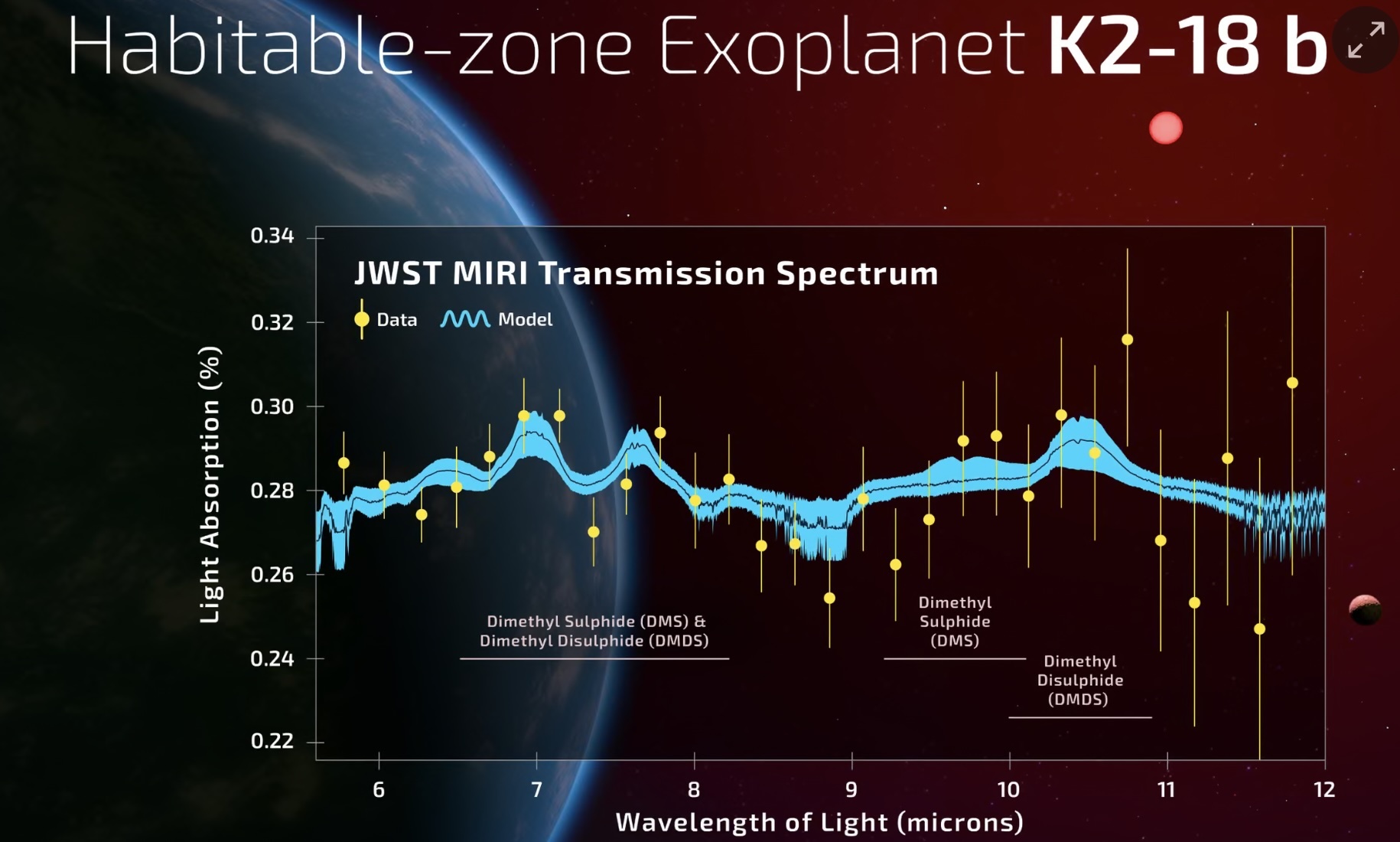

The Cambridge group has found that the atmosphere seems to contain the chemical signature of at least one of two molecules that are associated with life: dimethyl sulphide (DMS) and dimethyl disulphide (DMDS). On Earth, these gases are produced by marine phytoplankton and bacteria.

Prof Madhusudhan said he was surprised by how much gas was apparently detected during a single observation window.

"The amount we estimate of this gas in the atmosphere is thousands of times higher than what we have on Earth," he said.

"So, if the association with life is real, then this planet will be teeming with life," he added.

Prof Madhusudhan went further: "If we confirm that there is life on K2-18b, it should basically confirm that life is very common in the galaxy."

He told BBC Radio 5Live on Thursday: "This is a very important moment in science, but also very important to us as a species.

"If there is one example, and the universe being infinite, there is a chance for life on many more planets."

Dr Subir Sarkar, a lecturer in astrophysics at Cardiff University and part of the research team, said the research suggests K2-18b could have an ocean which could be potentially full of life - though he cautioned scientists "don't know for sure".

He added that the research team's work will continue to focus on looking for life on other planets: "Keep watching this space."

There are lots of "ifs" and "buts" at this stage, as Prof Madhusudhan's team freely admits.

Firstly, this latest detection is not at the standard required to claim a discovery.

For that, the researchers need to be about 99.99999% sure that their results are correct and not a fluke reading. In scientific jargon, that is a five sigma result.

These latest results are only three sigma, or 99.7%. Which sounds like a lot, but it is not enough to convince the scientific community. However, it is much more than the one sigma result of 68% the team obtained 18 months ago, which was greeted with much scepticism at the time.

But even if the Cambridge team obtains a five sigma result, that won't be conclusive proof that life exists on the planet, according to Prof Catherine Heymans of Edinburgh University and Scotland's Astronomer Royal, who is independent of the research team.

"Even with that certainty, there is still the question of what is the origin of this gas," she told BBC News.

"On Earth it is produced by microorganisms in the ocean, but even with perfect data we can't say for sure that this is of a biological origin on an alien world because loads of strange things happen in the Universe and we don't know what other geological activity could be happening on this planet that might produce the molecules."

That view is one the Cambridge team agree with. They are working with other groups to see if DMS and DMDS can be produced by non-living means in the lab.

"There is still a 0.3% chance that it might be a statistical fluke," Prof Madhusudhan said.

Suggesting life may exist on another planet was "a big claim if true", he told BBC Radio 4's Today programme, adding: "So we want to be really, really thorough, and make more observations, and get the evidence to the level that there is less than a one-in-a-million chance of it being a fluke."

He said this should be possible in "maybe one or two years".

Other research groups have put forward alternative, lifeless, explanations for the data obtained from K2-18b. There is a strong scientific debate not only about whether DMS and DMDS are present but also the planet's composition.

The reason many researchers infer that the planet has a vast liquid ocean is the absence of the gas ammonia in K2-18b's atmosphere. Their theory is that the ammonia is absorbed by a vast body of water below.

But it could equally be explained by an ocean of molten rock, which would preclude life, according to Prof Oliver Shorttle of Cambridge University.

"Everything we know about planets orbiting other stars comes from the tiny amounts of light that glance off their atmospheres. So it is an incredibly tenuous signal that we are having to read, not only for signs of life, but everything else," he said.

"With K2-18b part of the scientific debate is still about the structure of the planet."

Dr Nicolas Wogan at Nasa's Ames Research Center has yet another interpretation of the data. He published research suggesting that K2-18b is a mini gas giant with no surface.

Both these alternative interpretations have also been challenged by other groups on the grounds that they are inconsistent with the data from JWST, compounding the strong scientific debate surrounding K2-18b.

Prof Chris Lintott, presenter of the BBC's The Sky at Night, said he had "great admiration" for Prof Madhusudhan's team, but was treating the research with caution.

"I think we've got to be very careful about claiming that this is 'a moment' on the search to life. We've [had] such moments before," he told Today.

He said the research should be seen instead as "part of a huge effort to try and understand what's out there in the cosmos".

Prof Madhusudhan acknowledges that there is still a scientific mountain to climb if he is to answer one of the biggest questions in science. But he believes he and his team are on the right track.

"Decades from now, we may look back at this point in time and recognise it was when the living universe came within reach," he said.

"This could be the tipping point, where suddenly the fundamental question of whether we're alone in the universe is one we're capable of answering."

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Quelle: BBC

----

Update: 19.04.2025

.

Are we alone? New discovery raises hopes of finding alien life

he graph shows the observed transmission spectrum of the habitable zone exoplanet K2-18b using JWST MIRI spectrograph. Illustration: A. Smith, N. Madhusudhan (University of Cambridge)

Towards the end of his life, the cosmologist Stephen Hawking was asked about the odds of finding intelligent alien life in the next two decades. “The probability is low,” he declared in 2016, and took a lengthy pause before adding: “Probably.”

This week, other scientists from the University of Cambridge reported tentative evidence for two compounds in the atmosphere of a planet, K2-18b, that sits in the constellation of Leo 124 light years away.

On Earth, dimethyl sulphide (DMS) and dimethyl disulphide (DMDS) are hallmarks of life, emanating only from microscopic organisms. And while marine phytoplankton might not rank as particularly intelligent, the claim unleashed a wave of excitement: the answer to the question “Are we alone?” has never seemed closer.

“This is the strongest evidence to date for a biological activity beyond the solar system,” Prof Nikku Madhusudhan, an astrophysicist in the team, told the Guardian before the announcement.

“Decades from now, we may look back at this point in time and recognise it was when the living universe came within reach.”

Two more years of observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will nail down whether or not the compounds really exist in the planet’s atmosphere, Madhusudhan believes. The telescope – located about a million miles from Earth – is uniquely placed to make such measurements.

When a planet wanders across the face of its star, JWST can detect subtle shifts in the light it gathers, caused by compounds in the atmosphere absorbing starlight. Make enough observations and the measurements can confirm which compounds are abundant in the alien air.

But even if K2-18b’s atmosphere contains the two compounds, the question of life will not be solved: scientists cannot rule out that the chemicals form in other ways on other worlds, without calling on a cast of tiny aliens.

Conclusions, then, are hard to draw from the work, but the broader message is clear. Over the past decade or so, a swathe of technological advances and ambitious projects have transformed humanity’s chances of finding evidence for life elsewhere, says Monica Grady, emeritus professor of planetary science at the Open University.

“It’s partly because of new equipment,” she said. “JWST is a more powerful telescope than its predecessors because it can look at distant objects in greater detail. Some of the advances, though, result from new technologies applied to older equipment, or new methodologies applied to experimental techniques.”

Take the curious case of Venus. In 2020, a team led by Jane Greaves, an astronomer at Cardiff University, stunned the scientific community by publishing evidence for a pungent gas, phosphine, high up in the Venusian clouds.

They could find no other explanation for the gas beyond the presence of life. The work sparked an intense debate, but last year astrophysicists at Imperial College London found further evidence for phosphine in the planet’s atmosphere. To do so, they used a new detector fitted to the nearly 40-year-old James Clerk Maxwell telescope in Hawaii.

Newly devised analytical approaches are also boosting the search for alien life. Nasa’s Curiosity rover has been trundling around Gale crater on Mars for more than a decade.

In that time, it has drilled into rocks and studied the constituents of sediments that once lay at the bottom of an ancient lake bed. But it was a new analytical procedure that revealed the presence last month of long-chain alkanes on the planet, the largest organics found yet.

The compounds are not a smoking gun for life, but they are precisely what researchers find in rocks when biological cells degrade.

Software advances are coming, too. Scientists have not brought the full power of artificial intelligence to bear on vast quantities of historical observations that could be hiding signs of life, said .

Nor have major new telescopes, such as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) in South Africa and Australia, or the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile’s Atacama Desert, swung into action.

“The next decade promises to be even more exciting than the past one, in terms of moving closer to determining whether there is life beyond Earth,” Grady said.

If humans do share the cosmos with other life, much of it may be microbial. On Mars, scientists are looking for signs of microbes past or present, through biological remnants or waste gases such as methane emanating from bugs still eking out an existence deep in the Martian soil.

Intelligent life is considered a rarer prospect, but that hasn’t deterred efforts to find it.

The most extensive search, the Breakthrough Listen project, launched in 2016 with major telescopes around the world hoping to hear telltale signals or “technosignatures” from distant worlds.

To date, project scientists have detected interference from mobile phonesand overflying satellites, and got excited about one intriguing signal, but have heard nothing from clever aliens.

Future missions will soon join the search for life. Nasa’s Europa Clipper should arrive at Jupiter’s moon in 2030 and determine whether an ocean thought to lie beneath the icy crust can support life.

Soon after, another Nasa mission, the Habitable Worlds Observatory, is due to launch. It is the first telescope specifically designed to hunt for signs of life on planets around distant stars.

When might we have an answer? What constitutes proof? Caroline Freissinet, an analytical chemist who discovered the largest organics on Mars, says definitive evidence may forever be elusive, at least on Mars.

“The search for life on Mars is a question of probability,” she said. “The question is, at what probability can we start to claim that it’s life?

“Is it when we are 60% sure, or 90% sure? There is no answer to that. But we will never be 100% sure. Except if there is a marmot coming out of the ground and saying ‘hi’ to the camera.”

Quelle: The Guardian