7.04.2025

ESA releases first set of Euclid images and data

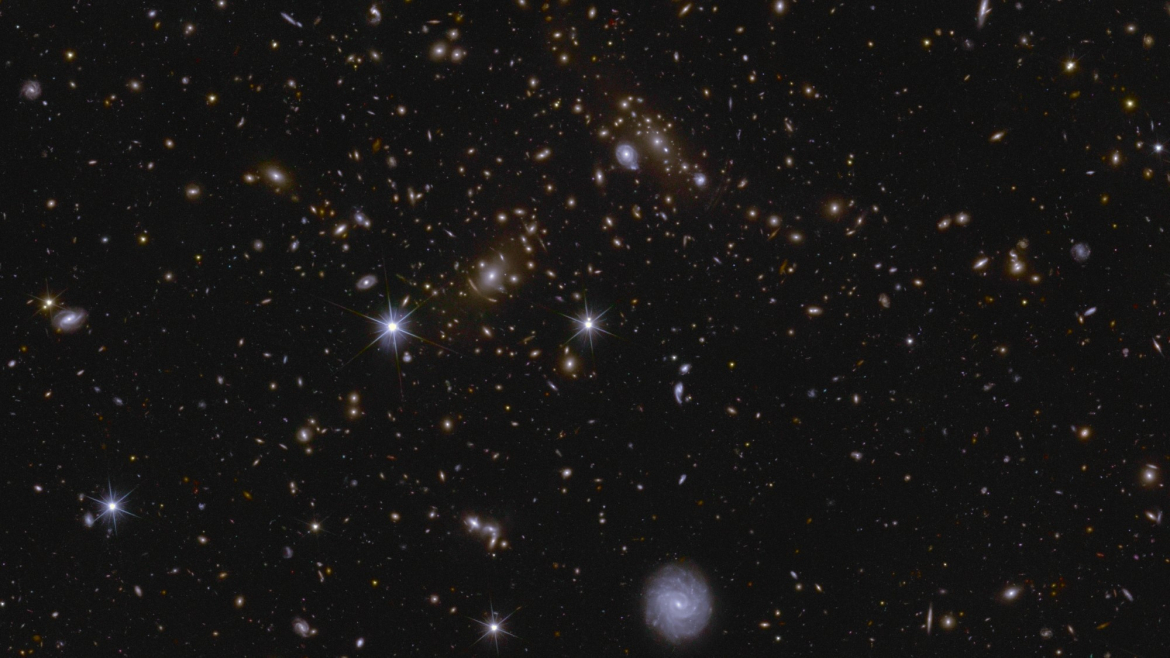

The European Space Agency (ESA) released the first batch of images and data for its Euclid space telescope. The images focus on Euclid’s three deep field areas, patches of sky the telescope will observe dozens of times to peer deep into the cosmos. Though the new release only contains Euclid’s first look into these areas, it has already provided astronomers with a treasure trove of data on galaxies and other cosmic phenomena.

Euclid was launched atop a Falcon 9 in early July 2023 on a mission to map nearly a third of the sky in incredible detail. With Euclid’s observations, astronomers want to explore the history of the universe and reveal the nature of dark energy and dark matter. Since the launch, ESA has published a few glimpses into the telescope’s capabilities, including spectacular views of nebulae, galaxies, galaxy clusters, and an image representing the first 1% of Euclid’s survey.

The latest release, Quick Data Release 1 (Q1), covers the largest area of the sky so far — 63 square degrees, or over 300 times the size of a full Moon — and results from only one week of observations. Astronomers collaborated with citizen scientists to train artificial intelligence (AI) to catalog hundreds of gravitational lenses and the shapes of hundreds of thousands of galaxies.

“It’s impressive how one observation of the deep field areas has already given us a wealth of data that can be used for a variety of purposes in astronomy: from galaxy shapes to strong lenses, clusters, and star formation, among others,” said Euclid project scientist Valeria Pettorino of ESA. “We will observe each deep field between 30 and 52 times over Euclid’s six-year mission, each time improving the resolution of how we see those areas and the number of objects we manage to observe. Just think of the discoveries that await us.”

Euclid’s three deep fields are known as North, South, and Fornax, named after their locations in the sky. The deep field North covers an area of 22.9 square degrees in the constellation of Draco. The most striking feature in this field is the Cat’s Eye Nebula, a cloud of dust 3,000 light-years from Earth, made of the leftovers from a dying star that shed its outer layers. The North field also contains the first Einstein ring Euclid discovered around a galaxy 590 million light-years away, as well as faint clouds of interstellar gas and dust in our own galaxy.

Explore the Euclid Deep Field North in ESASky.

Euclid’s view of the Cat’s Eye Nebula (Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre, E. Bertin, G. Anselmi)

The Fornax deep field is located in the southern constellation of the same name and covers an area of 12.1 square degrees. This area has been well studied by other observatories including the Hubble Space Telescope. Euclid’s Fornax deep field also includes the much smaller area studied by NASA’s Chandra X-ray telescope for its Deep Field South.

Explore the Euclid Deep Field Fornax in ESASky.

At 28.1 square degrees, Euclid’s Deep Field South is the largest of the three. No other deep survey has studied this area in the constellation of Horologium. Euclid’s view on this field reveals a part of the structure of the universe also known as the cosmic web, made from galaxy clusters connected by filaments of gas and dark matter.

Explore the Euclid Deep Field South in ESASky.

So far, Euclid has observed 26 million galaxies in the three deep fields, some of them as far as 10.5 billion light-years away. The Q1 release includes a catalog of 380,000 of these galaxies, categorized by their shapes and features.

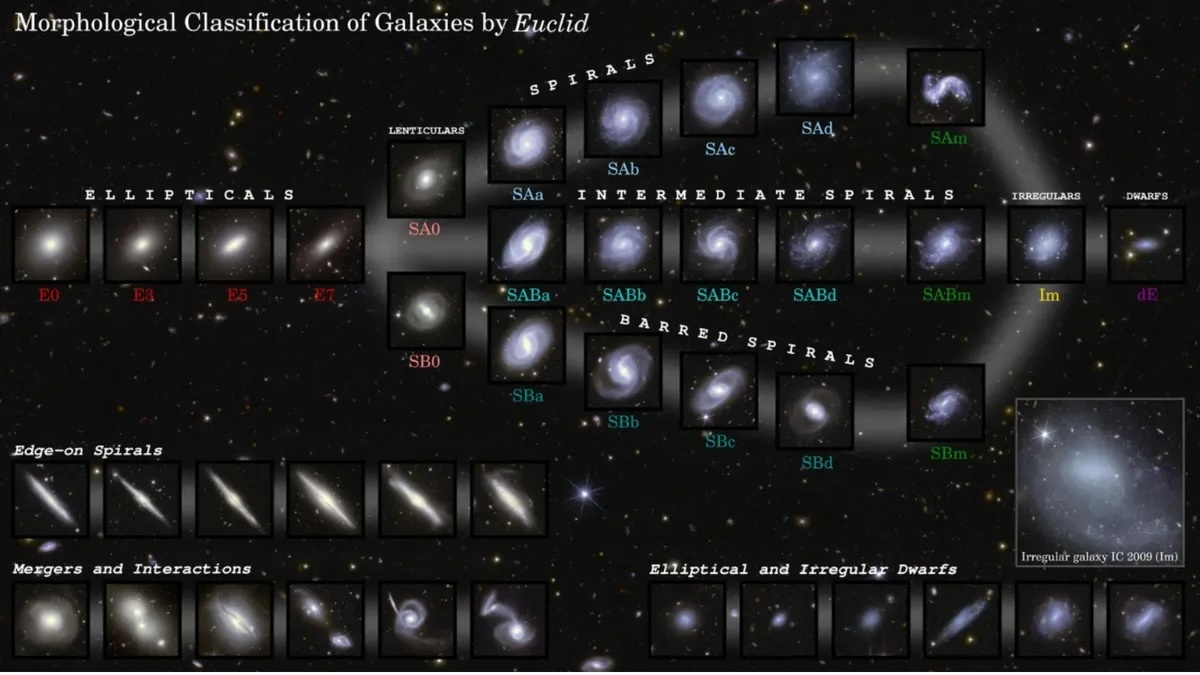

Collage of galaxies in different shapes selected from Euclid’s Q1 release by Zoobot. (Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by M. Walmsley, M. Huertas-Company, J.-C. Cuillandre)

“This collage is showing just a handful of galaxies from those images. Each one’s made up of billions of stars probably with billions of planets and each one is unique. Like a fingerprint,

they’re shaped by how they grew,” explained Euclid Consortium scientist Mike Walmsley of the University of Toronto, Canada. “Because light takes time to reach us, we’re looking back in time at how they used to look and that tells us about our own possible history.”

To quickly categorize the millions of galaxies in Euclid’s observations, astronomers enlisted the help of volunteers to train the Zoobot AI algorithm. In August 2024, 9,976 citizen scientists from the Galaxy Zoo project classified galaxies in Euclid’s images. After training on this data, Zoobot selected and classified the 380,000 galaxies in the newly released catalog.

“It takes millions of examples to train a good AI model from scratch, but we already have millions from other telescopes. And so, for Euclid, we only needed about a month of volunteer effort. We’re grateful to around 9,000 people who joined in to create enough new examples to fine-tune our models to work well for Euclid,” said Walmsley.

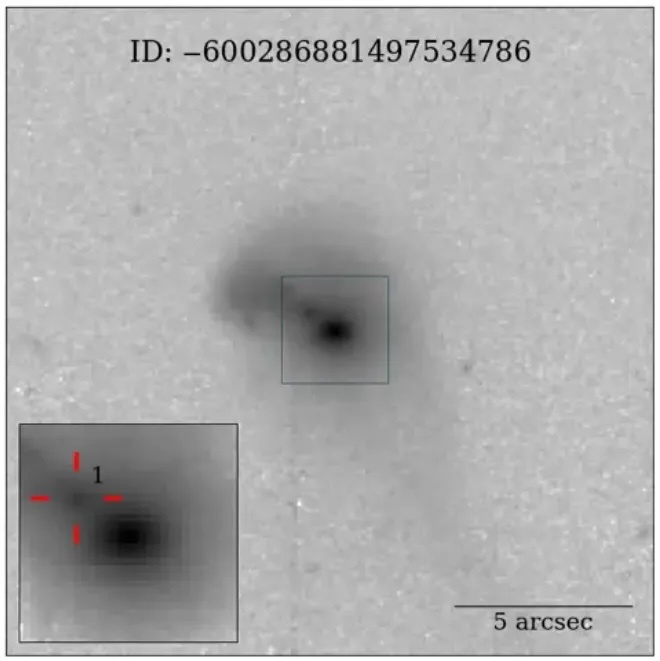

Collage of strong gravitational lenses in Euclid’s Q1 release. (Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by M. Walmsley, M. Huertas-Company, J.-C. Cuillandre)

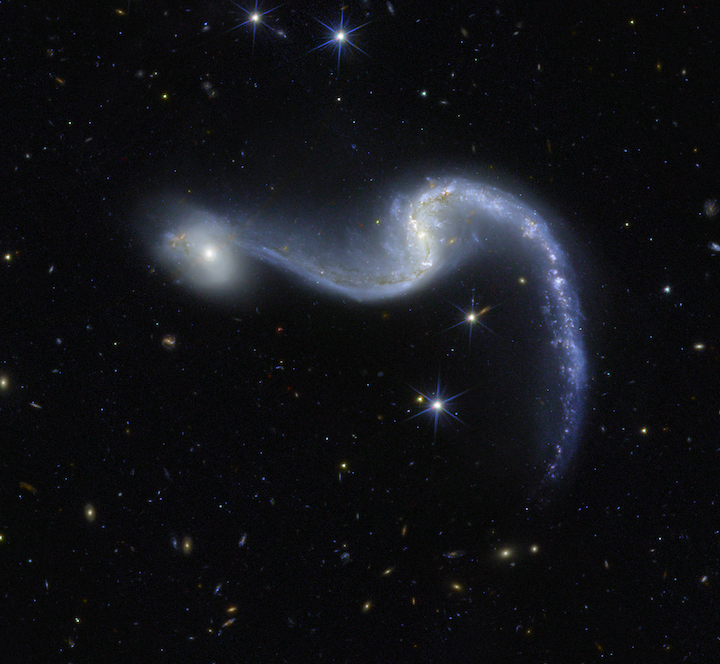

Another catalog included in the Q1 release lists nearly 500 strong gravitational lenses. Gravitational lensing is the result of gravity distorting the light from objects in space. As the light from a distant galaxy passes by a closer object, like a galaxy or black hole, it bends the gravitational pull from the normal and dark matter in the foreground. From our perspective, this effect creates a warped image of the distant object.

To find these strong lenses, astronomers also used AI and citizen scientists, but using a different process than for the galaxy catalog. First, the Zoobot algorithm scoured Euclid’s observations for potential strong lenses, which were then inspected by over 1,000 citizen scientists from the Space Warps project. Finally, experts and additional modeling narrowed down the selection to 497 strong lenses.

“Until now the vast majority of lenses have been found by ground-based telescopes and that’s because lenses are so rare that you need big chunks of sky to find them,” said Walmsley. “We simply haven’t had a space telescope that has the area, and the resolution, and the sensitivity to do that. Euclid is the first telescope which can find large numbers of lenses from space. By the time Euclid finishes, it will have found at least an order of magnitude more strong lenses than all previous searches put together.”

Location of Euclid’s Deep Fields. (Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA; ESA/Gaia/DPAC; ESA/Planck Collaboration)

The majority of strong lenses in Euclid’s catalog were not observed before. According to Walmsley, Euclid’s observations more than doubled the number of likely lenses that have been imaged from space. “That matters because we can see really important details in these lenses that are blurred out from the ground,” said Walmsley.

Euclid’s Q1 release only includes 0.4% of the number of galaxies the telescope is expected to observe throughout its mission. The complete catalog will be so big that astronomers can study the weak variant of gravitational lensing and potentially uncover the nature of dark matter and dark energy. The first full release of data to answer these cosmology questions is planned for next year.

Even though the Q1 release is small compared to the full release, Euclid’s scientists have already written 34 scientific papers based on the data, which will be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. A preprint of these papers was made available alongside the Q1 release. With the data now available to the scientific community and the public, Euclid promises to answer many questions about the universe.

“Euclid shows itself once again to be the ultimate discovery machine. It is surveying galaxies on the grandest scale, enabling us to explore our cosmic history and the invisible forces shaping our Universe,” said ESA’s Director of Science, Prof. Carole Mundell.

Quelle: NSF

----

Update: 6.11.2025

.

Euclid peers through a dark cloud’s dusty veil

This shimmering view of interstellar gas and dust was captured by the European Space Agency’s Euclid space telescope. The nebula is part of a so-called dark cloud, named LDN 1641. It sits at about 1300 light-years from Earth, within a sprawling complex of dusty gas clouds where stars are being formed, in the constellation of Orion.

In visible light this region of the sky appears mostly dark, with few stars dotting what seems to be a primarily empty background. But, by imaging the cloud with the infrared eyes of its NISP instrument, Euclid reveals a multitude of stars shining through a tapestry of dust and gas.

This is because dust grains block visible light from stars behind them very efficiently but are much less effective at dimming near-infrared light.

The nebula is teeming with very young stars. Some of the objects embedded in the dusty surroundings spew out material – a sign of stars being formed. The outflows appear as magenta-coloured spots and coils when zooming into the image.

In the upper left, obstruction by dust diminishes and the view opens toward the more distant Universe with many galaxies lurking beyond the stars of our own galaxy.

Euclid observed this region of the sky in September 2023 to fine-tune its pointing ability. For the guiding tests, the operations team required a field of view where only a few stars would be detectable in visible light; this portion of LDN 1641 proved to be the most suitable area of the sky accessible to Euclid at the time.

The tests were successful and helped ensure that Euclid could point reliably and very precisely in the desired direction. This ability is key to delivering extremely sharp astronomical images of large patches of sky, at a fast pace. The data for this image, which is about 0.64 square degrees in size – or more than three times the area of the full Moon on the sky – were collected in just under five hours of observations.

Euclid is surveying the sky to create the most extensive 3D map of the extragalactic Universe ever made. Its main objective is to enable scientists to pin down the mysterious nature of dark matter and dark energy.

Yet the mission will also deliver a trove of observations of interesting regions in our galaxy, like this one, as well as countless detailed images of other galaxies, offering new avenues of investigation in many different fields of astronomy.

[Technical details: The colour image was created from NISP observations in the Y-, J- and H-bands, rendered blue, green and red, respectively. The size of the image is 11 232 x 12 576 pixels. The jagged boundary is due to the gaps in the array of NISP’s sixteen detectors, and the way the observations were taken with small spatial offsets and rotations to create the whole image. This is a common effect in astronomical wide-field images.]

[Image description: The focus of the image is a portion of LDN 1641, an interstellar nebula in the constellation of Orion. In this view, a deep-black background is sprinkled with a multitude of dots (stars) of different sizes and shades of bright white. Across the sea of stars, a web of fuzzy tendrils and ribbons in varying shades of orange and brown rises from the bottom of the image towards the top-right like thin coils of smoke.]

Quelle: ESA

----

Update: 20.11.2025

.