22.03.2025

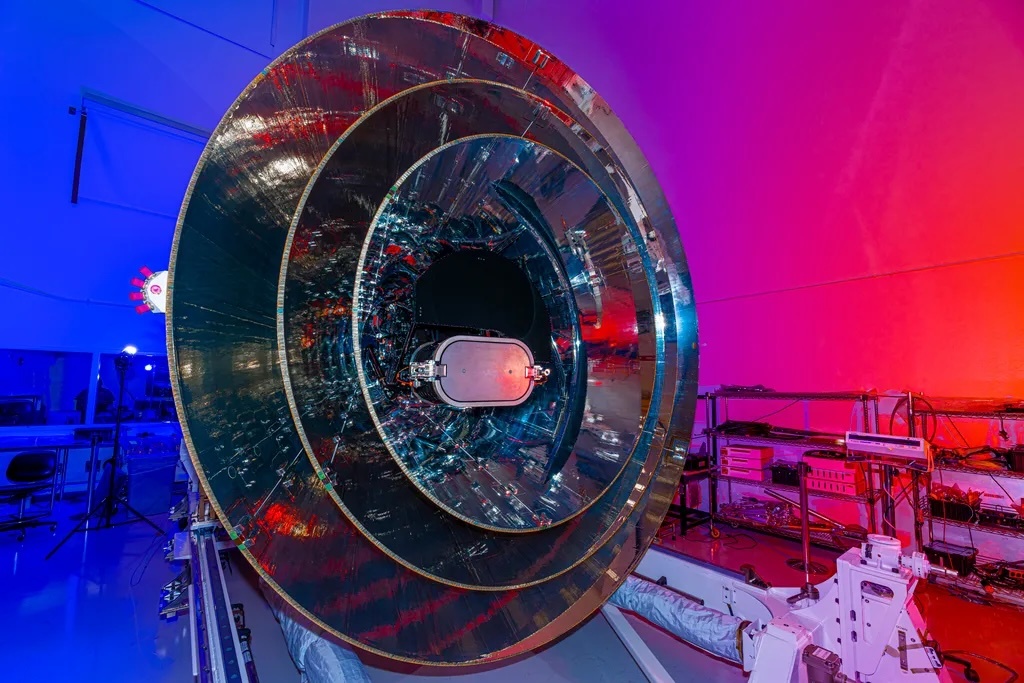

The telescope on NASA’s SPHEREx observatory was protected during launch by its dust cover — the oval metal plate shown here at the center of the three photon shields.

Credit: BAE Systems/NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s SPHEREx space observatory, which launched into low Earth orbit on March 11, has opened its eyes to the sky. On March 18, the mission team commanded the spacecraft to eject the protective dust cover that shielded the telescope opening. Once science operations begin several weeks from now, SPHEREx (short for Specto-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer) will map the entire celestial sky to answer fundamental questions about the universe.

Measuring about 25 inches by 16 inches (64 centimeters by 40 centimeters), the cover kept particles and moisture off key pieces of hardware, including three telescope mirrors. To complete the ejection, engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California sent a command to SPHEREx that activated two mechanical release mechanisms on the protective lid, and springs helped push it away from the observatory. After being ejected, the cover began to float away and will eventually burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.

The mission won’t power on the spacecraft’s camera until it has cooled to its operating temperature, which is colder than minus 300 degrees Fahrenheit (about minus 190 degrees Celsius). So to confirm the cover’s removal, team members observed a change in SPHEREx’s orientation — essentially, a slight jiggle of the observatory after each mechanism release. Shortly after the second jiggle, the telescope’s temperature began to drop, indicating it was exposed to the cold of space as planned.

The SPHEREx spacecraft is about the size of a subcompact car. The telescope is the portion of the observatory that collects light from distant stars and galaxies. Only about the size of a washing machine, it is nestled inside three cone-shaped photon shields that protect the instrument from light and heat from the Sun and Earth.

During its two-year prime mission, the observatory will use a technique called spectroscopy to create four all-sky maps featuring 102 wavelengths, or colors, of infrared light. This information can help scientists measure the distance to faraway galaxies, identify chemicals and molecules in cosmic gas clouds, and more.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 3.04.2025

.

NASA’s SPHEREx Takes First Images, Preps to Study Millions of Galaxies

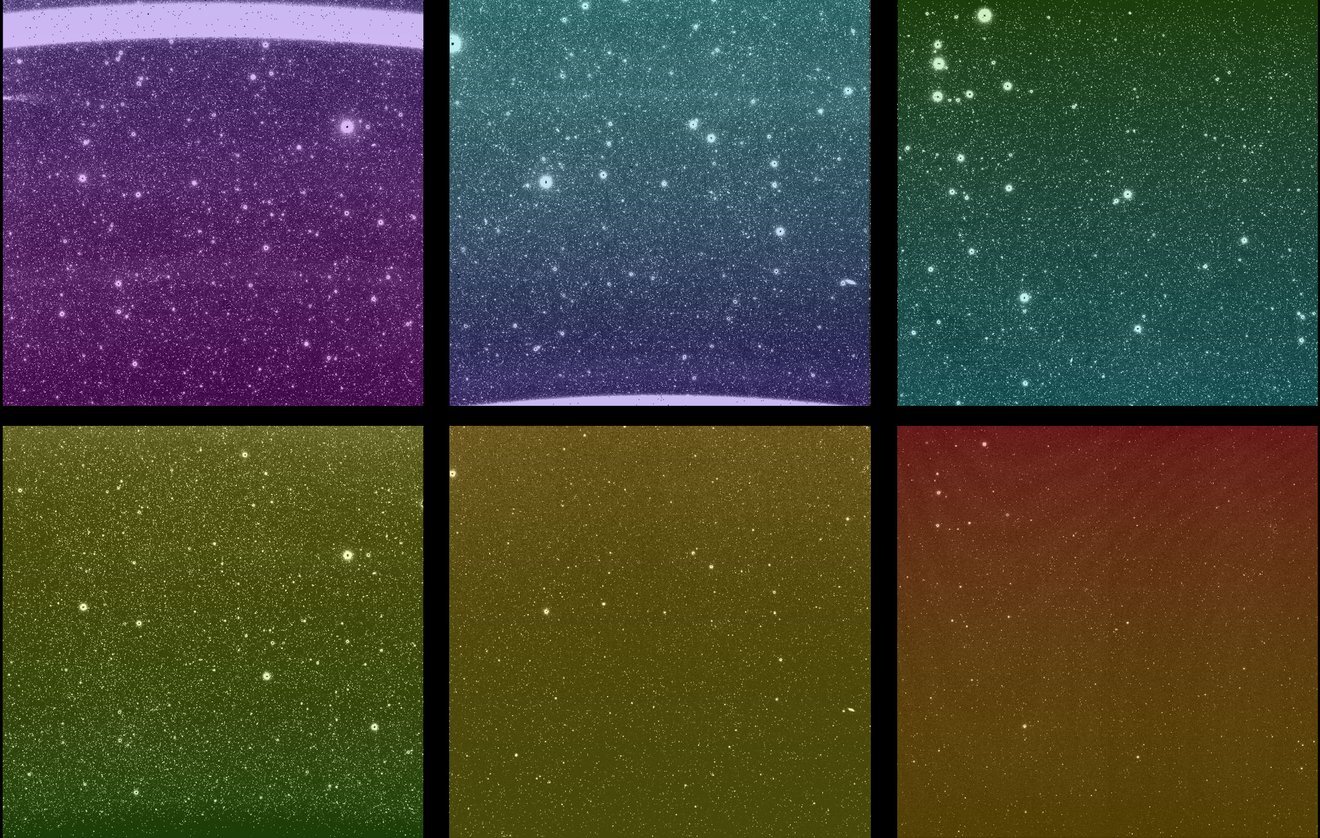

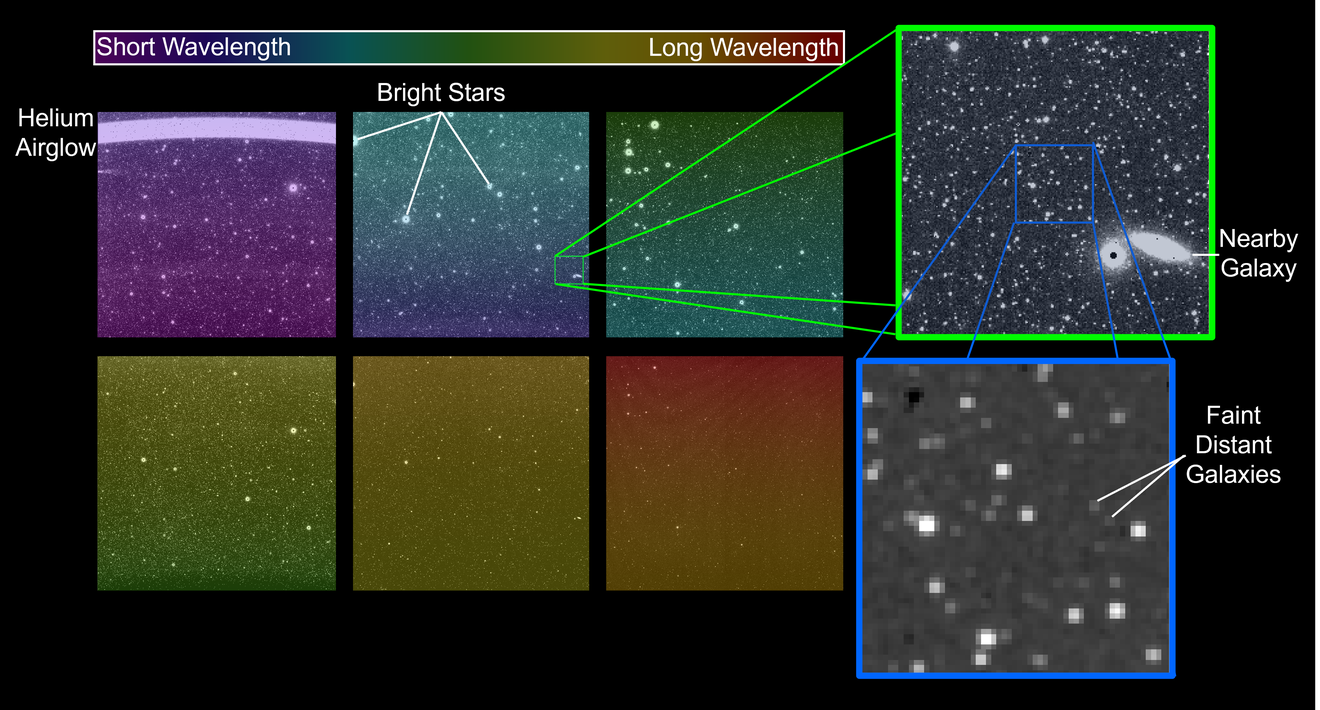

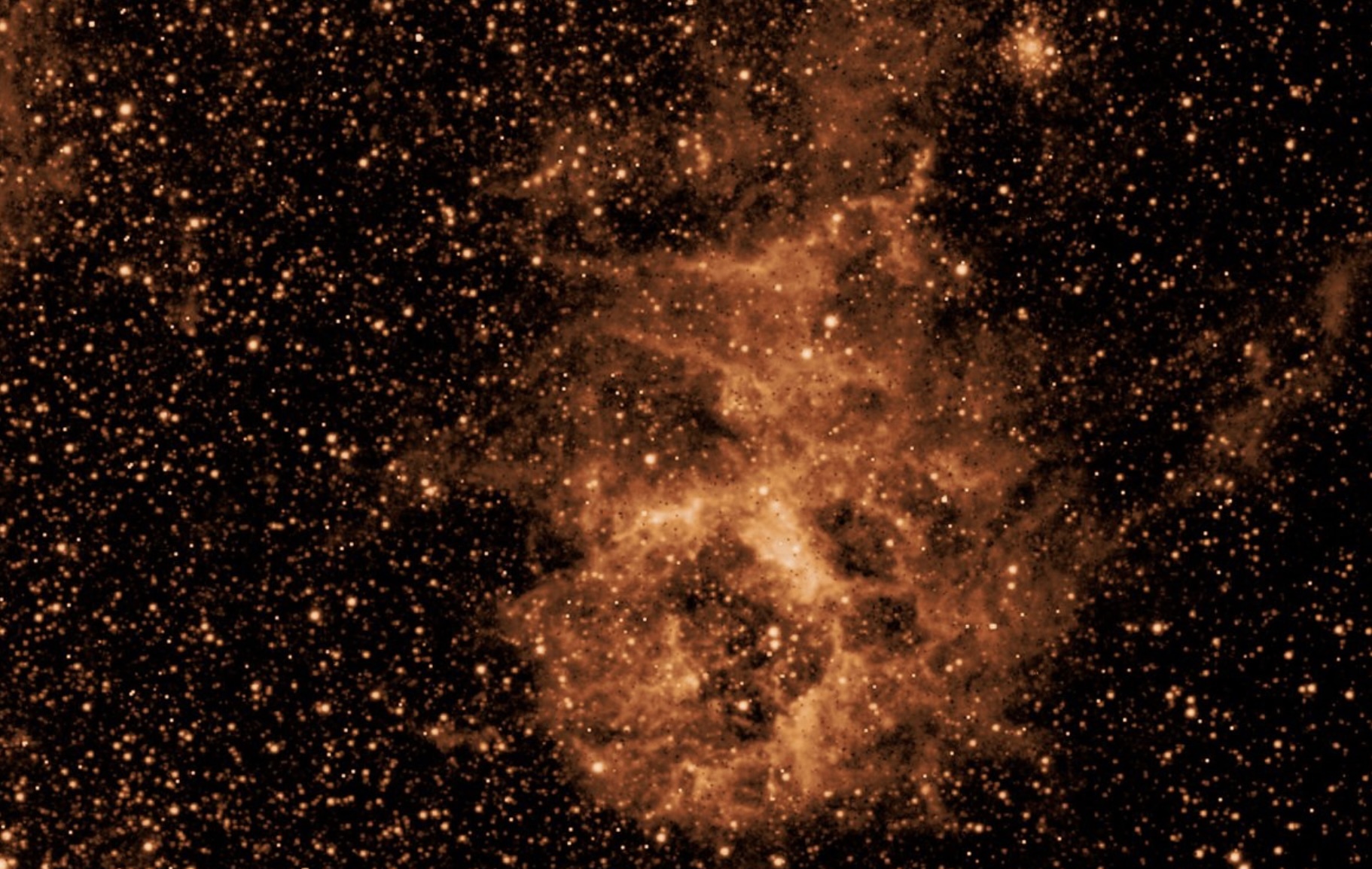

NASA’s SPHEREx, which will map hundreds of millions of galaxies across the entire sky, captured one of its first exposures March 27. The observatory’s six detectors each captured one of these uncalibrated images, to which visible-light colors have been added to represent infrared wavelengths. SPHEREx’s complete field of view spans the top three images; the same area of the sky is also captured in the bottom three images.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Processed with rainbow hues to represent a range of infrared wavelengths, the new pictures indicate the astrophysics space observatory is working as expected.

NASA’s SPHEREx (short for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer) has turned on its detectors for the first time in space. Initial images from the observatory, which launched March 11, confirm that all systems are working as expected.

Although the new images are uncalibrated and not yet ready to use for science, they give a tantalizing look at SPHEREx’s wide view of the sky. Each bright spot is a source of light, like a star or galaxy, and each image is expected to contain more than 100,000 detected sources.

There are six images in every SPHEREx exposure — one for each detector. The top three images show the same area of sky as the bottom three images. This is the observatory’s full field of view, a rectangular area about 20 times wider than the full Moon. When SPHEREx begins routine science operations in late April, it will take approximately 600 exposures every day.

Each image in this uncalibrated SPHEREx exposure contains more than 100,000 detected sources, including stars and galaxies. The two insets at right zoom in on sections of one image, showcasing the telescope’s ability to capture faint, distant galaxies. These sections are processed in grayscale rather than visible-light color for ease of viewing. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“Our spacecraft has opened its eyes on the universe,” said Olivier Doré, SPHEREx project scientist at Caltech and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, both in Southern California. “It’s performing just as it was designed to.”

The SPHEREx observatory detects infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye. To make these first images, science team members assigned a visible color to every infrared wavelength captured by the observatory. Each of the six SPHEREx detectors has 17 unique wavelength bands, for a total of 102 hues in every six-image exposure.

Breaking down color this way can reveal the composition of an object or the distance to a galaxy. With that data, scientists can study topics ranging from the physics that governed the universe less than a second after its birth to the origins of water in our galaxy.

“This is the high point of spacecraft checkout; it’s the thing we wait for,” said Beth Fabinsky, SPHEREx deputy project manager at JPL. “There’s still work to do, but this is the big payoff. And wow! Just wow!”

During the past two weeks, scientists and engineers at JPL, which manages the mission for NASA, have executed a series of spacecraft checks that show all is well so far. In addition, SPHEREx’s detectors and other hardware have been cooling down to their final temperature of around minus 350 degrees Fahrenheit (about minus 210 degrees Celsius). This is necessary because heat can overwhelm the telescope’s ability to detect infrared light, which is sometimes called heat radiation. The new images also show that the telescope is focused correctly. Focusing is done entirely before launch and cannot be adjusted in space.

“Based on the images we are seeing, we can now say that the instrument team nailed it,” said Jamie Bock, SPHEREx’s principal investigator at Caltech and JPL.

How It Works

Where telescopes like NASA’s Hubble and James Webb space telescopes were designed to target small areas of space in detail, SPHEREx is a survey telescope and takes a broad view. Combining its results with those of targeted telescopes will give scientists a more robust understanding of our universe.

The observatory will map the entire celestial sky four times during its two-year prime mission. Using a technique called spectroscopy, SPHEREx will collect the light from hundreds of millions of stars and galaxies in more wavelengths any other all-sky survey telescope.

Track the real-time location of NASA’s SPHEREx space observatory — in polar orbit about 404 miles above Earth — using the agency’s 3D visualization tool, Eyes on the Solar System. The spacecraft will complete four all-sky maps in its 27-month primary mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

When light enters SPHEREx’s telescope, it’s directed down two paths that each lead to a row of three detectors. The observatory’s detectors are like eyes, and set on top of them are color filters, which are like color-tinted glasses. While a standard color filter blocks all wavelengths but one, like yellow- or rose-tinted glasses, the SPHEREx filters are more like rainbow-tinted glasses: The wavelengths they block change gradually from the top of the filter to the bottom.

“I’m rendered speechless,” said Jim Fanson, SPHEREx project manager at JPL. “There was an incredible human effort to make this possible, and our engineering team did an amazing job getting us to this point.”

More About SPHEREx

The SPHEREx mission is managed by JPL for the agency’s Astrophysics Division within the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters. BAE Systems (formerly Ball Aerospace) built the telescope and the spacecraft bus. The science analysis of the SPHEREx data will be conducted by a team of scientists located at 10 institutions in the U.S., two in South Korea, and one in Taiwan. Caltech managed and integrated the instrument. Data will be processed and archived at IPAC at Caltech. The mission’s principal investigator is based at Caltech with a joint JPL appointment. The SPHEREx dataset will be publicly available at the NASA-IPAC Infrared Science Archive. Caltech manages JPL for NASA.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 3.05.2025

.

NASA’s SPHEREx Space Telescope Begins Capturing Entire Sky

After weeks of preparation, the space observatory has begun its science mission, taking about 3,600 unique images per day to create a map of the cosmos like no other.

Launched on March 11, NASA’s SPHEREx space observatory has spent the last six weeks undergoing checkouts, calibrations, and other activities to ensure it is working as it should. Now it’s mapping the entire sky — not just a large part of it — to chart the positions of hundreds of millions of galaxies in 3D to answer some big questions about the universe. On May 1, the spacecraft began regular science operations, which consist of taking about 3,600 images per day for the next two years to provide new insights about the origins of the universe, galaxies, and the ingredients for life in the Milky Way.

“Thanks to the hard work of teams across NASA, industry, and academia that built this mission, SPHEREx is operating just as we’d expected and will produce maps of the full sky unlike any we’ve had before,” said Shawn Domagal-Goldman, acting director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “This new observatory is adding to the suite of space-based astrophysics survey missions leading up to the launch of NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Together with these other missions, SPHEREx will play a key role in answering the big questions about the universe we tackle at NASA every day.”

From its perch in Earth orbit, SPHEREx peers into the darkness, pointing away from the planet and the Sun. The observatory will complete more than 11,000 orbits over its 25 months of planned survey operations, circling Earth about 14½ times a day. It orbits Earth from north to south, passing over the poles, and each day it takes images along one circular strip of the sky. As the days pass and the planet moves around the Sun, SPHEREx’s field of view shifts as well so that after six months, the observatory will have looked out into space in every direction.

This video shows SPHEREx’s field of view as it scans across one section of sky inside the Large Magellanic Cloud, with rainbow colors representing the infrared wavelengths the telescope’s detectors see. The view from one detector array moves from purple to green, followed by the second array’s view, which changes from yellow to red. The images are looped four times.

When SPHEREx takes a picture of the sky, the light is sent to six detectors that each produces a unique image capturing different wavelengths of light. These groups of six images are called an exposure, and SPHEREx takes about 600 exposures per day. When it’s done with one exposure, the whole observatory shifts position — the mirrors and detectors don’t move as they do on some other telescopes. Rather than using thrusters, SPHEREx relies on a system of reaction wheels, which spin inside the spacecraft to control its orientation.

Hundreds of thousands of SPHEREx’s images will be digitally woven together to create four all-sky maps in two years. By mapping the entire sky, the mission will provide new insights about what happened in the first fraction of a second after the big bang. In that brief instant, an event called cosmic inflation caused the universe to expand a trillion-trillionfold.

“We’re going to study what happened on the smallest size scales in the universe’s earliest moments by looking at the modern universe on the largest scales,” said Jim Fanson, the mission’s project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “I think there’s a poetic arc to that.”

Cosmic inflation subtly influenced the distribution of matter in the universe, and clues about how such an event could happen are written into the positions of galaxies across the universe. When cosmic inflation began, the universe was smaller than the size of an atom, but the properties of that early universe were stretched out and influence what we see today. No other known event or process involves the amount of energy that would have been required to drive cosmic inflation, so studying it presents a unique opportunity to understand more deeply how our universe works.

“Some of us have been working toward this goal for 12 years,” said Jamie Bock, the mission’s principal investigator at Caltech and JPL. “The performance of the instrument is as good as we hoped. That means we’re going to be able to do all the amazing science we planned on and perhaps even get some unexpected discoveries.”

Color Field

The SPHEREx observatory won’t be the first to map the entire sky, but it will be the first to do so in so many colors. It observes 102 wavelengths, or colors, of infrared light, which are undetectable to the human eye. Through a technique called spectroscopy, the telescope separates the light into wavelengths — much like a prism creates a rainbow from sunlight — revealing all kinds of information about cosmic sources.

For example, spectroscopy can be harnessed to determine the distance to a faraway galaxy, information that can be used to turn a 2D map of those galaxies into a 3D one. The technique will also enable the mission to measure the collective glow from all the galaxies that ever existed and see how that glow has changed over cosmic time.

And spectroscopy can reveal the composition of objects. Using this capability, the mission is searching for water and other key ingredients for life in these systems in our galaxy. It’s thought that the water in Earth’s oceans originated as frozen water molecules attached to dust in the interstellar cloud where the Sun formed.

The SPHEREx mission will make over 9 million observations of interstellar clouds in the Milky Way, mapping these materials across the galaxy and helping scientists understand how different conditions can affect the chemistry that produced many of the compounds found on Earth today.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 8.07.2025

.

NASA Telescope Snaps First Images of Universe After Vandenberg Launch

Months after arriving in orbit thanks to a Falcon 9 rocket launch from Vandenberg Space Force Base, NASA’s newest space telescope has started collecting images of the universe.

The craft known as SPHEREx — Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer — shared a ride with another NASA mission for the trek on March 11.

NASA’s newest space observatory began regular science operations May 1, gathering about 3,600 images per day. Images from the sky survey will be added to public archives on a weekly basis, making it available to everyone.

“Because we’re looking at everything in the whole sky, almost every area of astronomy can be addressed by SPHEREx data,” said Rachel Akeson, the lead for the SPHEREx Science Data Center that’s part of a facility for astrophysics and planetary science at Caltech in Pasadena.

While not the first mission to map the sky, SPHEREx observations involve 102 wavelengths, or colors, of infrared light, which are undetectable to the human eye.

By comparison, a now-retired craft collected images in just four wavelength bands.

Scientists intend to use the new data to study the distribution of frozen water and organic molecules — all considered the “building blocks of life” — in the Milky Way.

Releasing SPHEREx data in a public archive should lead to far more astronomical studies than the team alone could complete, officials said.

“By making the data public, we enable the whole astronomy community to use SPHEREx data to work on all these other areas of science,” Akeson said.

Since arriving in low-Earth orbit, SPHEREx spent six weeks getting checked out and undergoing calibration to make sure it was ready to begin work.

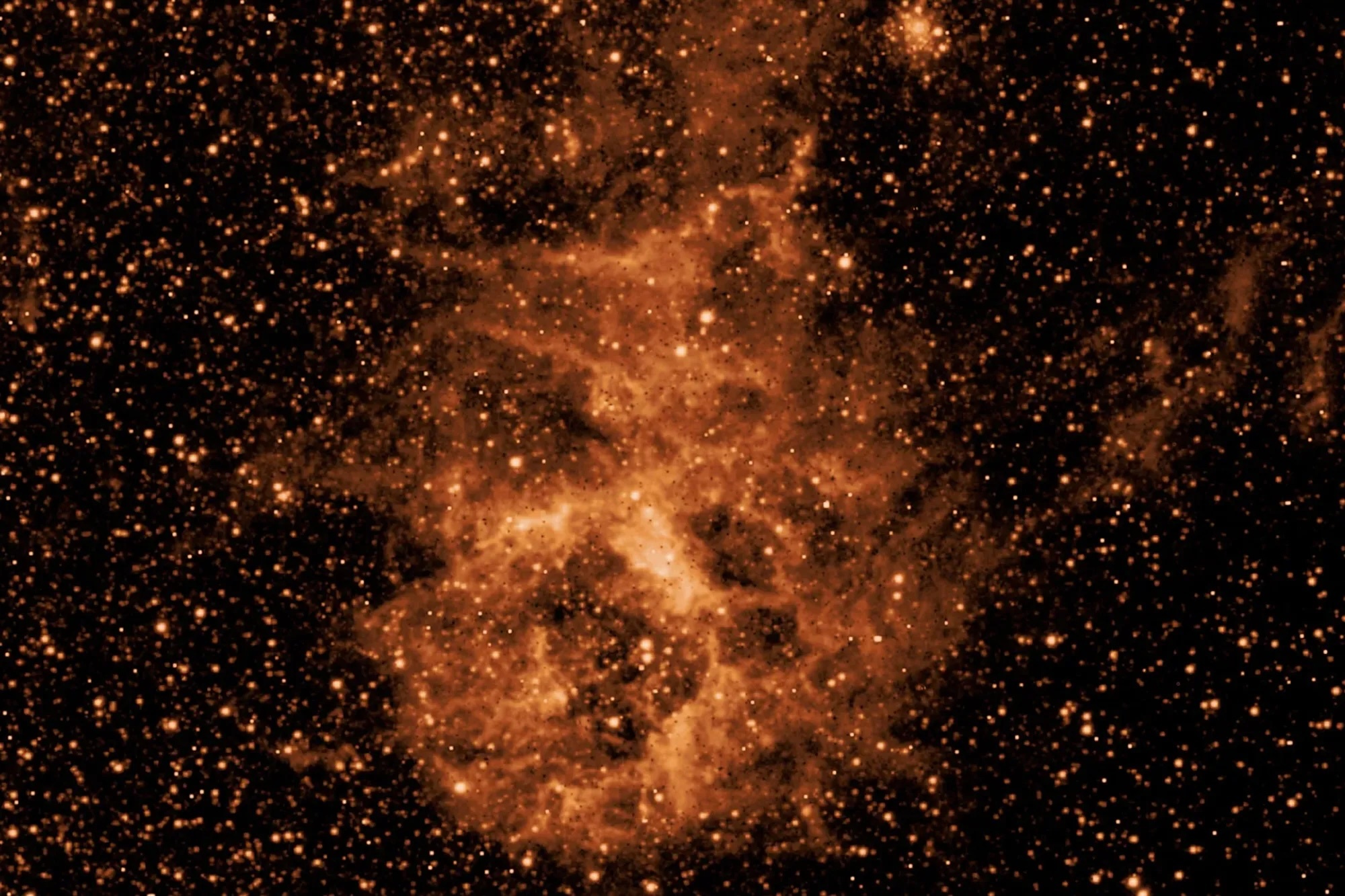

A soot-like cloud is revealed in a section of the sky in this May 1 image from NASA’S SPHEREx space observatory. NASA/JPL-Caltech photo

The first images have delighted scientists involved in the mission for years.

“Some of us have been working toward this goal for 12 years,” said Jamie Bock, the mission’s principal investigator at Caltech and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “The performance of the instrument is as good as we hoped. That means we’re going to be able to do all the amazing science we planned on and perhaps even get some unexpected discoveries.”

SPHEREx images will appear in the public archive within 60 days after the telescope collects each observation, officials said.

The delay will allow the SPHEREx team to process the raw data to remove or flag artifacts and align the images to the correct astronomical coordinates.

Procedures employed to process the data also will be provided with the images.

“We want enough information in those files that people can do their own research,” Akeson said.

During its 25 months of operations, the observatory is expected to complete more than 11,000 orbits, circling Earth about 14½ times a day

SPHEREx will survey the entire sky twice a year, meaning it will create four all-sky maps in its two years of operation.

After the mission reaches the one-year mark, the team plans to release a map of the entire sky at all 102 wavelengths, according to NASA.

Quelle: Noozhawk

----

Update: 12.11.2025

.

Deep space exploration as NASA’s SPHEREx maps the galaxies

In a world that often measures itself in days, years, decades and centuries, a second seems insignificant. But a lot can happen in an instant. It takes a lightning bolt just 30 microseconds to strike a tree or a house, for example. When you touch something hot or cold, it takes the nerve impulse mere milliseconds to reach your brain. And when you use your computer or smartphone, it takes the hardware only a few billionths of a second to interpret the click of your mouse or the tap of your finger.To truly comprehend what’s possible in the span of a second, however, consider the big bang — the miraculous moment some 13.8 billion years ago when a very tiny, very dense and very hot speck of energy and matter began to suddenly expand, creating the universe as we know it today. A phenomenon known as “inflation,” that initial moment of abrupt and exponential expansion lasted only a fraction of a second, according to astrophysicist John Wisniewski, who says the universe expanded a trillion-trillionfold in less than the blink of an eye.Although scientists are confident that inflation occurred, they don’t yet understand how it actually happened. A new and novel NASA mission that’s currently underway hopes to change that. Launched in March from California’s Vandenberg Space Force Base, the Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer (SPHEREx) mission will spend the next two years plotting the entire celestial sky to create a 3D map of more than 450 million galaxies using technology that’s never been deployed before. Doing so could help scientists understand for the first time what happened immediately after the big bang, says Wisniewski, who serves as program scientist for the SPHEREx mission.“SPHEREx is all about origins,” Wisniewski explains. “It’s mapping out the three-dimensional distribution of hundreds of millions of galaxies in our universe, which is going to allow us to answer a fundamental question: What caused inflation? In other words, how did the universe start? That is a pretty big origin question.”

Investigating Inflation

To understand the physics behind inflation, SPHEREx is using a technique known as spectroscopy. Basically, it’s capturing infrared light — light emitted by warm objects, including stars and galaxies, in wavelengths that are invisible to the human eye — and separating it into 102 distinct colors, the same way prisms split sunlight into rainbows. Observing those colors can help scientists analyze objects’ composition and, in the case of galaxies, calculate their distance from Earth.“We’re a space telescope that’s mapping the entire sky in spectroscopy, which has never been done before,” says Jamie Bock, SPHEREx’s principal investigator and a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology. “When you cover the whole sky and capture all these colors, it’s an incredible dataset. There’s a ton of things you can do with that.”To seek answers about inflation, scientists will scrutinize the celestial layout of galaxies next to each other in groups, which looks haphazard but is actually conspicuously organized. “Galaxies cluster, and clustering was set up in the early universe,” Bock explains. “If we study the distribution of galaxies in three dimensions, how they cluster can tell us something about the process of inflation.”But inflation isn’t the only phenomenon SPHEREx is investigating. In addition to understanding how the universe formed, it will attempt to understand how galaxies grow over time, which it can accomplish by measuring fluctuations in extragalactic background light — a faint glow of light from outside our galaxy, the source of which is accumulated radiation from all the stars that have ever existed in the observable universe.“With SPHEREx, we can see what the total glow produced by galaxies is,” Bock says. “That glow encodes all emissions over cosmic history. So, by studying it, we can work out in an independent way what the history of light production was.”A third and final goal of SPHEREx is to take an inventory of frozen water and carbon dioxide in our galaxy, which could shed light on the origins of life. “We know that water is important for life on Earth, and it may be important for life elsewhere,” explains Bock, who says scientists believe the water on Earth traveled there after initially developing inside clouds that form in the space between stars. “There’s basically these interstellar reservoirs of water in space, but that water is actually in the form of ice.”By determining where in the galaxy that ice exists and under what circumstances, SPHEREx could help explain how water forms and the processes that deliver it to planets such as Earth.

To answer the big questions, it wants to answer, SPHEREx relies on a novel design, the centerpiece of which is three concentric metallic cones that help protect the telescope from the heat of Earth and the sun.“SPHEREx is in low Earth orbit, which is approximately 400 miles above Earth. To do the sensitive infrared observations that it’s designed to do, you need to get the telescope really cold — down to temperatures of about minus 350 degrees Fahrenheit,” Wisniewski says. “To get to that temperature, you’d normally have to go out much farther, to approximately 1 million miles above Earth. Or you’d have to use active coolants.”Although active coolants such as cryogen are effective, they’re finite, they add complexity and weight to the spacecraft, and they require electricity.“SPHEREx is doing all of its cooling using a passive radiator,” continues Wisniewski, who says the aforementioned cones give SPHEREx a distinctive martini-glass shape. “The martini glass — what we call photon shields — is basically reflecting earthshine and sunshine away from the telescope.”Also unique are SPHEREx’s linear-variable filters, which the telescope uses to efficiently separate infrared light into myriad discrete colors without the use of bulky parts or moving components. Basically, as it scans the sky, the telescope observes stars and galaxies multiple times through different parts of the same filter, capturing a different wavelength of infrared light every time.“With these spectral filters, the wavelength we capture varies along the length of the filter, and therefore over the length of the detector that the filter is sandwiched over,” explains Beth Fabinsky, SPHEREx project manager. “If we point at something, we get one color. If we nudge our pointing a tiny bit, we get a slightly different color. That’s how we collect multiple spectra for a single object in the sky.”Adds Wisniewski, “Imagine that the camera in your iPhone can only observe red, orange and yellow in the top part of the camera and can only observe green, blue and violet in the bottom part of the camera. That’s what a linear-variable filter does. It allows you to observe one color in one part of the camera and another color in another part. So, if you want to take a selfie in full color, you basically have to take two pictures — one that puts yourself in the bottom part of the camera and one that puts yourself in the top part of the camera. SPHEREx is doing exactly this, which is a really novel way to get all-sky coverage extremely fast.”

‘A Natural Human Question’

Over its 25 months of planned survey operations, SPHEREx will complete more than 11,000 orbits, circling Earth about 14.5 times per day and capturing hundreds of thousands of images that will be digitally woven together to create four different maps of the entire observable sky. NASA has promised to make those maps — which will contain encyclopedic information about hundreds of millions of celestial objects, including stars, galaxies and asteroids — freely available to scientists around the world.“It’s going to be a literal treasure trove for decades for the current and next generation of astronomers,” Wisniewski says.It’s not just astronomers who should be excited by SPHEREx, however. It’s everyone, insists Bock. “SPHEREx is all about understanding the origin of the universe, the origin of our galaxy and the origin of materials that foster life on Earth,” he says. “I can’t think of a single person on Earth who doesn’t want to know where we come from and how it all started. It’s a natural human question.”

Quelle: USA TODAY