4.02.2025

Japan’s fledgling space defense sector is taking its cues from the US Space Development Agency, which is pursuing a novel concept based on constellations of small satellites and maximum use of existing commercial technologies. Space policy researcher Umeda Kota discusses the challenges facing Japan as it embraces the SDA’s “proliferated architecture” for military communications, missile detection and tracking, and other purposes.

On December 4, 2024, the US Space Force (USSF) activated a new unit at Yokota Air Base in western Tokyo to support the operations of US Forces Japan in the space domain. At a meeting the previous month, the Japanese and US defense ministers welcomed the launch of the unit, US Space Forces Japan, as a milestone in space defense cooperation—an area that has seen rapid progress in recent years—and affirmed their governments’ commitment to further deepen the partnership.

In a parallel development, Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force’s Space Cooperation and Innovation Office, opened in 2023 in Toranomon Hills in central Tokyo, has been engaging with the commercial sector with the aim of mobilizing cutting-edge civilian aerospace technology for military purposes. This focus reflects a growing recognition in Japan—as in the United States—that military utilization of advanced civilian technology is vital to the future development of our space defense capabilities. But what exactly do people mean when they talk about using civilian space technology for military purposes? In the following, I introduce innovative American and Japanese initiatives in this domain and touch on the challenges facing Japan going forward.

DoD Innovation Programs in the Crosshairs

In the mid-2010s, the US Department of Defense began defense innovation initiatives to maintain the superiority of American military technology over China’s in particular. It created multiple internal innovation entities centered on the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU). These entities have made use of flexible contracting tools with the aim of accelerating the adoption of cutting-edge commercial technologies for military use.

Since then, the DoD’s innovation units have accumulated a track record of technological development, in some cases leading to acquisition of new defense systems. However, with China’s rapid military modernization threatening America’s technological supremacy, the DoD’s approach has come under criticism from various quarters. Todd Harrison, senior researcher at the American Enterprise Institute, has said that the department needs to put more energy into capitalizing on projects already underway and less into launching new units. Former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research Melissa Flagg in a report pointed out that, because the innovation units are not plugged into the procurement processes for individual branches of the military, even projects that result in the development of promising prototypes rarely lead to the acquisition (that is, budget itemization) of new systems, which should be the aim of any innovation program.

In short, while such DoD innovation units as the DIU, AFWERX, and SpaceWERX have had some measure of success in the development of specific cutting-edge technologies, their impact on the operational effectiveness of the US armed forces has been limited.

Building a New Space Architecture

In the space domain, however, military acquisition is undergoing a major overhaul by initiatives of the US Space Development Agency (SDA). Established in 2019 as an entity reporting directly to the Under Secretary of Defense (Research and Engineering), the SDA describes itself as a “constructive disruptor for space acquisition.”

The US Space Force currently operates a relatively small fleet of large-scale satellites with highly advanced capabilities for missions such as early warning and military communications. Unfortunately, such satellites are highly vulnerable to ground-launched missile attacks, and destruction of even one could seriously compromise US military capabilities. The time and costs involved in the development of a single satellite have also drawn criticism.

As explained by SDA Director Derek Tournear, the USSF is subject to the “innovator’s dilemma”—the difficulty large organizations face in pursuing wholesale innovation while simultaneously maintaining and improving tried-and-true systems and technologies. By contrast, the SDA, as an agency independent from the Space Force, has been able to introduce a completely new approach.

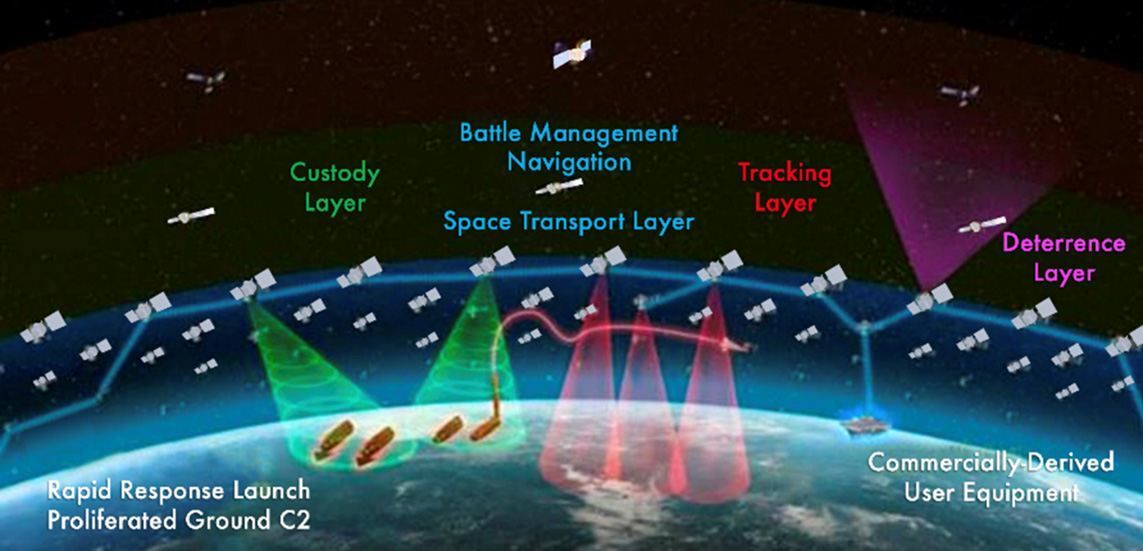

The two keywords heard in this context are “proliferated” and “spiral development.” “Proliferated” refers to the concept of creating a “constellation” of hundreds of relatively low-cost satellites to create a resilient space architecture that can withstand attacks on individual satellites. “Spiral development” is a model for launching a new generation (or “tranche”) of small satellites every two years to continually upgrade this proliferated architecture. The SDA began launching its demonstration satellites, referred to as Tranche O, in April 2023. The launch of Tranche 1 is scheduled for 2025, and the agency has already published a request for proposals for Tranche 3, to be launched in 2028.

Representation of the US Space Development Agency’s Space Architecture (Source: Space Development Agency.)

The SDA was placed under the jurisdiction of the US Space Force in October 2022, but it maintains a high degree of independence, and its budget has increased year by year. In fact, Congress has allocated more than requested for the SDA’s space architecture in recognition of its value. In keeping with this shift in emphasis, the USSF, in its 2024 budget request, communicated its intent to cancel one of five large satellites it was developing for early missile warning purposes. Recounting the five-year-old USSF’s operational achievements in a speech last December, Chief of Space Operations Chance Salzman placed the demonstration of the SDA’s proliferated architecture at the top of the list.

The innovation that the SDA has brought to the USFF is not the outcome of cutting-edge research and development. It is the product of a novel approach, predicated on a new space architecture and operational concept, that facilitates rapid procurement while controlling costs and technological risk through maximum use of existing commercial technologies.

Japan’s Fledgling Space Defense Program

Now let us turn our attention to Japan. At present, the Ministry of Defense and the Self-Defense Forces have just three satellite systems in operation, all of them DSN “Kirameki” military communications satellites. The reason for this state of affairs is that the SDF’s use of satellites was subject to strict constitutional constraints until the enactment of the Basic Space Law in 2008. What this means is that construction of a national defense space architecture is still in its infancy in Japan, and the future is wide open for the development and deployment of various satellite systems.

The Defense Ministry has already taken significant steps in the direction of using integrated constellations of small satellites for security purposes, emulating the SDA’s approach. For example, the SDF has been using SpaceX’s Starlink and Eutelsat’s OneWeb communications satellites on a trial basis to boost the resiliency of military communications. Furthermore, the Defense Ministry’s fiscal 2025 draft budget includes plans to begin work on a satellite constellation that would facilitate the detection and tracking of long-range military targets. Construction under this program, a private-public partnership known as a private finance initiative (PFI), could begin as early as March 2026. Japanese and US defense authorities are also hammering out plans for collaboration on a satellite constellation for early warning and tracking of ballistic missiles and hypersonic glide vehicles.

The abovementioned PFI project is especially noteworthy in that it is designed to quickly secure new capabilities by making maximum use of existing commercial technologies. It speaks to the recent emergence of a domestic ecosystem for space development and utilization, integrating innovative space services (supplied largely by startups) with the commercial sector’s accumulated know-how in the area of space development.

Integration Challenges

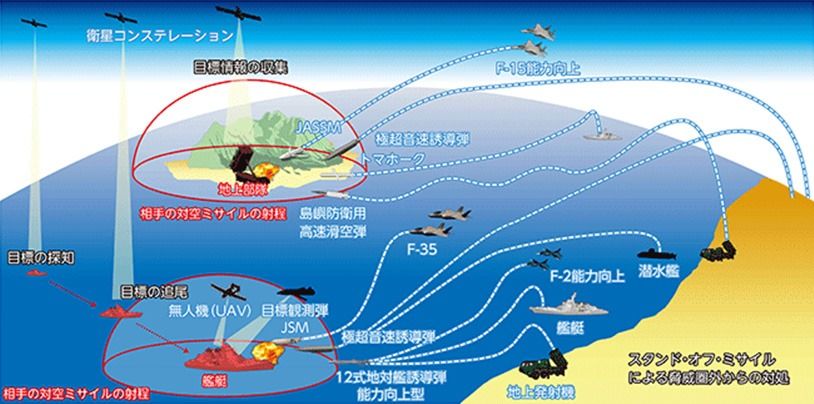

In this way, the Defense Ministry and SDF are pursuing a number of innovative programs and working actively to tap into commercial technologies. But the devil will be in the details. Building a target detection and tracking system is a huge technological challenge in and of itself, but an even bigger problem is how to integrate such a system with the SDF’s ground-based operations. The planned satellite constellation for long-range target detection and tracking is only meaningful as an integral component of the broader “standoff defense capability”—that is, the ability to strike targets outside of Japan’s territorial area—called for in the 2022 National Security Strategy.

A visualization of Japanese plans for a standoff defense capability, published in the Defense Ministry’s white paper, Defense of Japan 2024. The report calls for collection and integrated analysis of intelligence from multiple sources, including a constellation of small satellites.

Although I have focused on a single example, the problem of integrating space-based systems with ground-based operational concepts is likely to emerge in a variety of contexts as one of the key challenges facing the Japanese military establishment going forward. Apart from some strategic-level intelligence, neither the SDF nor other Japanese organizations involved in space development have acquired any experience or know-how in this area. In the end, however, Tokyo has little choice but to forge ahead with the development and integration of space defense systems in order to respond to today’s challenging security environment.

In October 2024, the Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics Agency established the Defense Innovation Science and Technology Institute in Tokyo. According to public statements, the institute will take on paradigm-changing research while at the same time working to promote rapid development of new military applications for existing technology. Both are important aspects of defense innovation.

We have seen how the United States and Japan are striving to acquire new defense capabilities in the space domain by building satellite systems that make use of existing commercial technologies. If these initiatives are successful, they could contribute significantly to the defense capabilities of both countries. The key issue for Japan will be integrating the functions of a space defense system with the SDF’s ground-based operational concepts. It will not be easy, but it is a hurdle that Japan must overcome if it is to meet the defense challenges of the twenty-first century.

Quelle: nippon.com