29.12.2024

Nelson: Decision on Mars Sample Return expected before new administration takes office

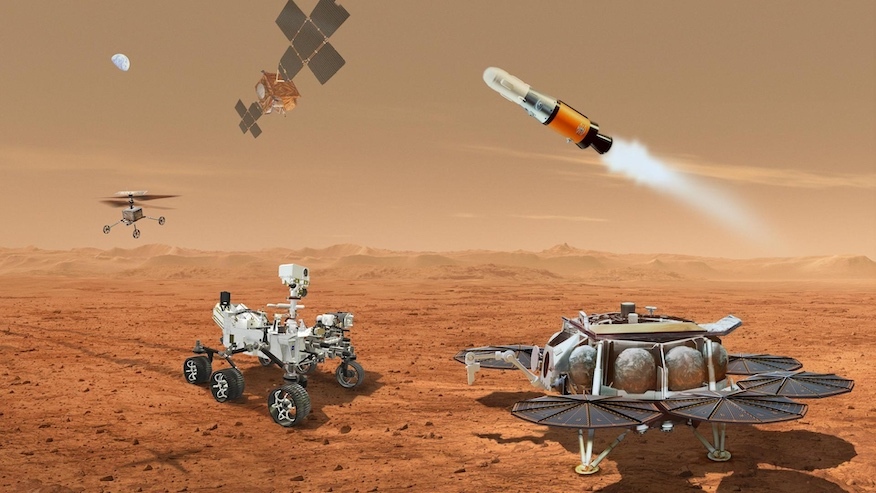

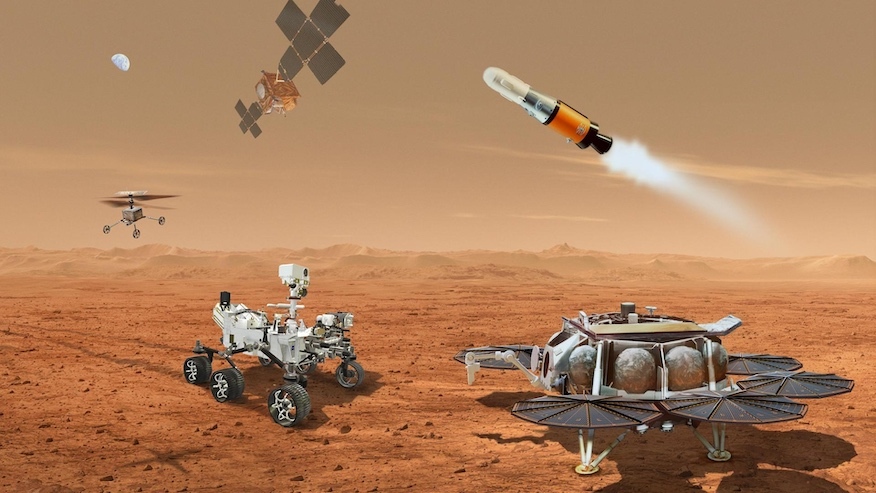

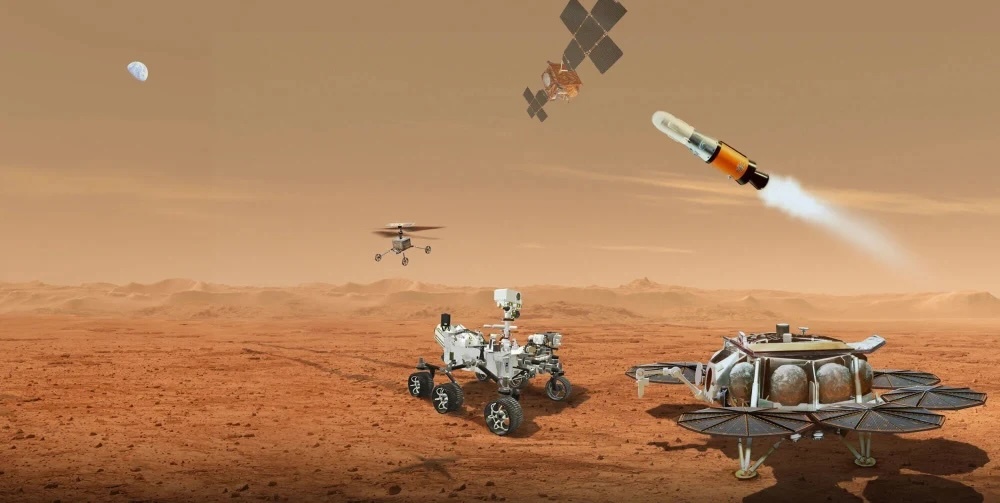

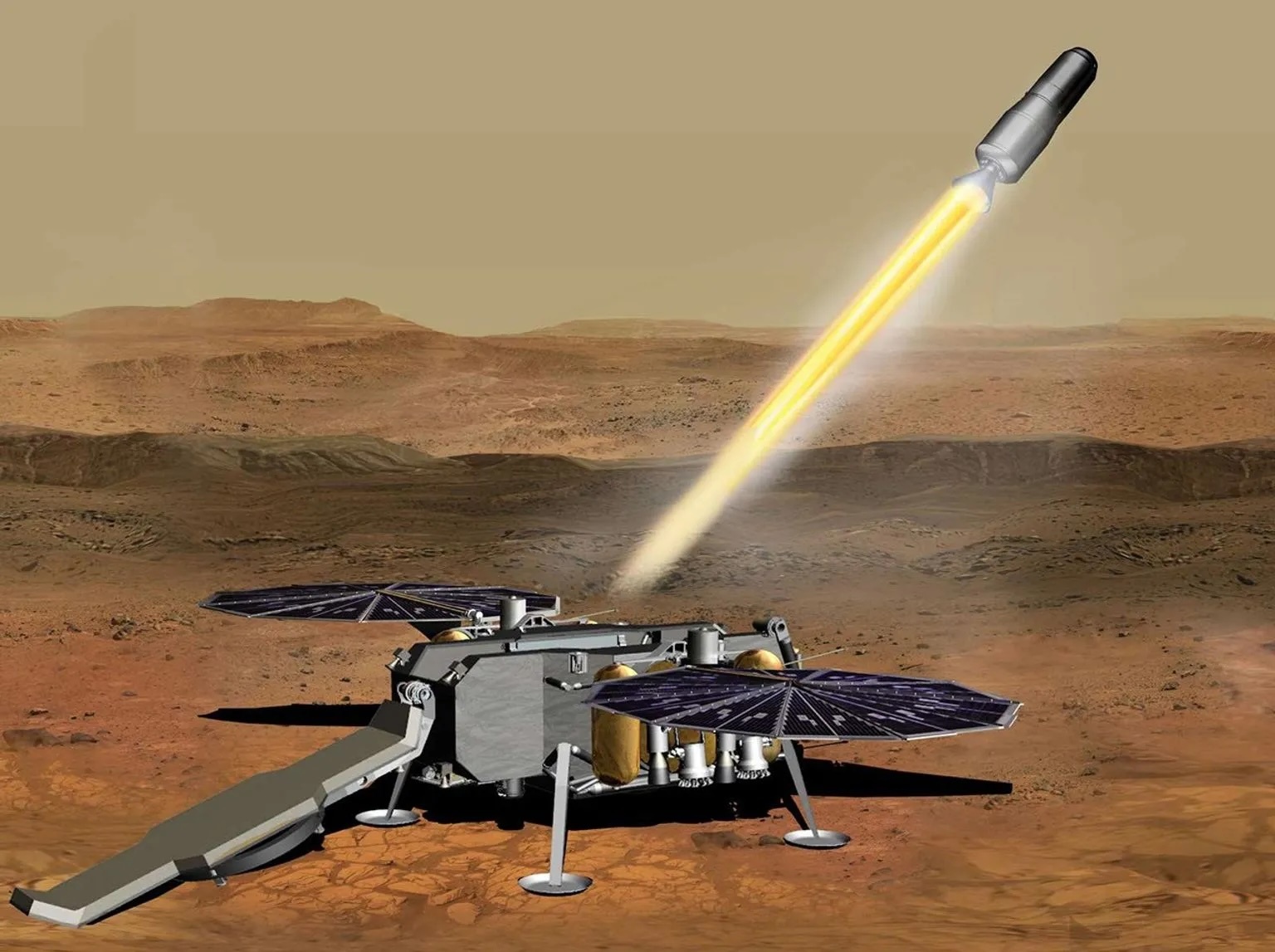

This illustration shows a concept for multiple robots that would team up to ferry to Earth samples of rocks and soil being collected from the Martian surface by NASA’s Mars Perseverance rover.

Credit: NASA/ESA/JPL-Caltech

One of the biggest decision points for the space community, how to redesign the Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission, may be weeks away from an inflection point, according to outgoing NASA Administrator Bill Nelson.

During a roundtable discussion with reporters on Dec. 18 at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Nelson said the agency will announce the path forward on the U.S.-led initiative to return samples from the Red Planet “in the first part of January, before I leave.”

“As a matter of fact, one of the major briefings is going to occur Friday morning (Dec. 20) here at KSC,” Nelson said. “I’ve already been briefed in part. At the end of the day, I’m the decider on this stage and then we had that off to the new administration.”

A consensus inside NASA and in the broader scientific community was that the timeline for MSR and its cost was untenable. The report of the Independent Review Board, published in September 2023, suggested a mission cost of $11 billion and a return date of 2040.

Nelson said that was “way too expensive.” He also noted that NASA intended to have astronauts on Mars by the 2040s and NASA wants to be able to have those samples to study before crews start arriving.

“And so, I pulled the plug on it. And lo and behold what’s coming out and we’ll give you the results in probably the first week in January,” Nelson said. “What’s coming out is by involving industry, and not NASA centers like [the Jet Propulsion Laboratory], combining with others, they’re coming out with much more practical (proposals), where they can speed up the time and considerably lower the cost.”

Changing course

Mars Sample Return was first laid out back in 2009 as part of what was known as the ExoMars program, a partnership between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). Fast forward to August 2020, NASA established the Independent Review Board to evaluate the early architecture for the mission.

It would require a robotic rover to collect samples, the NASA Sample Retrieval Lander (SRL) with a so-called “fetch” rover to retrieve the samples and then ESA’s Earth Return Orbiter (ERO) to bring them back to Earth.

By this point, about a third of the architecture, connected to the collection of samples was in motion. The Mars Perseverance rover launched atop a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas 5 rocket less than a month before. It went onto reach the Red Planet with its 43 cylindrical collection tubes in February 2021.

Back on Earth, before Perseverance arrived at Mars, the first Independent Review Board included that the cost of MSR for the United States would be at least $2.9-3.3 billion, nearly a billion more than initial estimates. Additionally that review board cautioned that “we do not believe the program’s schedule and cost are aligned with its scope,” arguing that launching the in 2026 timeframe was “not achievable.”

In March 2021, Northrop Grumman received a contract from NASA valued at up to $84.5 million to provide first- and second-stage solid-fuel motors for the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV), which would take the samples from the SRL up to Mars orbit where the ERO would be waiting.

Nearly a year later, in February 2022, NASA awarded a trio of contracts to Lockheed Martin connected to the SRL and the MAV. It received $35 million from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) to “produce the cruise stage and its comprehensive elements, including the solar arrays, structure, propulsion and thermal properties” for the SRL.

For the MAV, Lockheed Martin received $194 million from NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center to “design, build, test and deliver the rocket” and $2.6 million from JPL for preliminary design work on the Earth Entry System, which would shield the samples as they made their return to Earth.

“It’s a great responsibility to be entrusted to solve the technical challenges of this groundbreaking mission. We’re looking forward to helping NASA blaze new trails in scientific discovery,” said Lisa Callahan, Lockheed Martin’s vice president and general manager of the company’s Commercial Civil Space business at the time.

In order to get a more wholistic view of the mission ahead of the confirmation process (formally establishing schedule, cost and technical baselines), NASA convened a second Independent Review Board, chaired by NASA’s former Mars Czar, Orlando Figueroa, in spring 2023. It was through that analysis that the new timeline of returning samples in the 2040s emerged, along with the cost ballooning to around $11 billion.

The report was made public in the fall and discussed during an Oct. 20 meeting of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group Steering Committee.

“Technical issues indicated to us that the early planning dates for a ’27 or ’28 launch were simply not credible, a near zero probability that we’d be able to do it,” Figueroa said during the meeting. “Moving to 2030 offers an opportunity, and looks it is possible, but [President Biden’s] budget doesn’t quite support that.”

Because Congress is still mired in its budgeting process, opting instead to pass continuing resolutions instead of a new, complete package of spending bills, the funds available to NASA for MSR remains uncertain.

New players enter the picture

In an announcement made in April 2024, NASA stated that it was going back to the drawing board on MSR and was reaching out to industry players as well as the various NASA centers to provide alternative architectures that would get samples back from Mars cheaper and faster.

By June, the agency listed 11 studies that it was examining to find that new path. The agency awarded $1.5 million contracts to eight companies to further their studies in addition to supporting studies from JPL and Johns Hopkins’ Applied Physics Laboratory (APL).

Those companies included big names, like Aerojet Rocketdyne, Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman and SpaceX as well as those like Quantum Space and Whittinghill Aerospace. Rocket Lab’s proposal was accepted after the initial announcement and made public in October.

In regard to Nelson’s announcement earlier this month about the forthcoming decision and its timing, the administrator said it was part of the “normal cycle of making decisions” and said it was “unrelated to the new administration.”

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 5.01.2025

.

NASA to Host Media Call Highlighting Mars Sample Return Update

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and Nicky Fox, associate administrator, Science Mission Directorate, will host a media teleconference at 1 p.m. EST, Tuesday, Jan. 7, to provide an update on the status of the agency’s Mars Sample Return Program.

The briefing will include NASA’s efforts to complete its goals of returning scientifically selected samples from Mars to Earth while lowering cost, risk, and mission complexity.

Audio of the media call will stream live on the agency’s website.

Media interested in participating by phone must RSVP no later than two hours prior to the start of the call to: dewayne.a.washington@nasa.gov. A copy of NASA’s media accreditation policy is online.

The agency’s Mars Sample Return Program has been a major long-term goal of international planetary exploration for more than two decades. NASA’s Perseverance rover is collecting compelling science samples that will help scientists understand the geological history of Mars, the evolution of its climate, and prepare for future human explorers. The return of the samples also will help NASA’s search for signs of ancient life.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 9.01.2025

.

NASA overhauls plan to bring samples from Mars back to Earth

NASA on Tuesday announced an overhaul to its plan to collect samples from Mars and return them to Earth.

Agency officials said they have decided to scrap parts of their original plan to cut down on the mission’s technical difficulty and cost and to shorten the timeline for when the samples could be brought back.

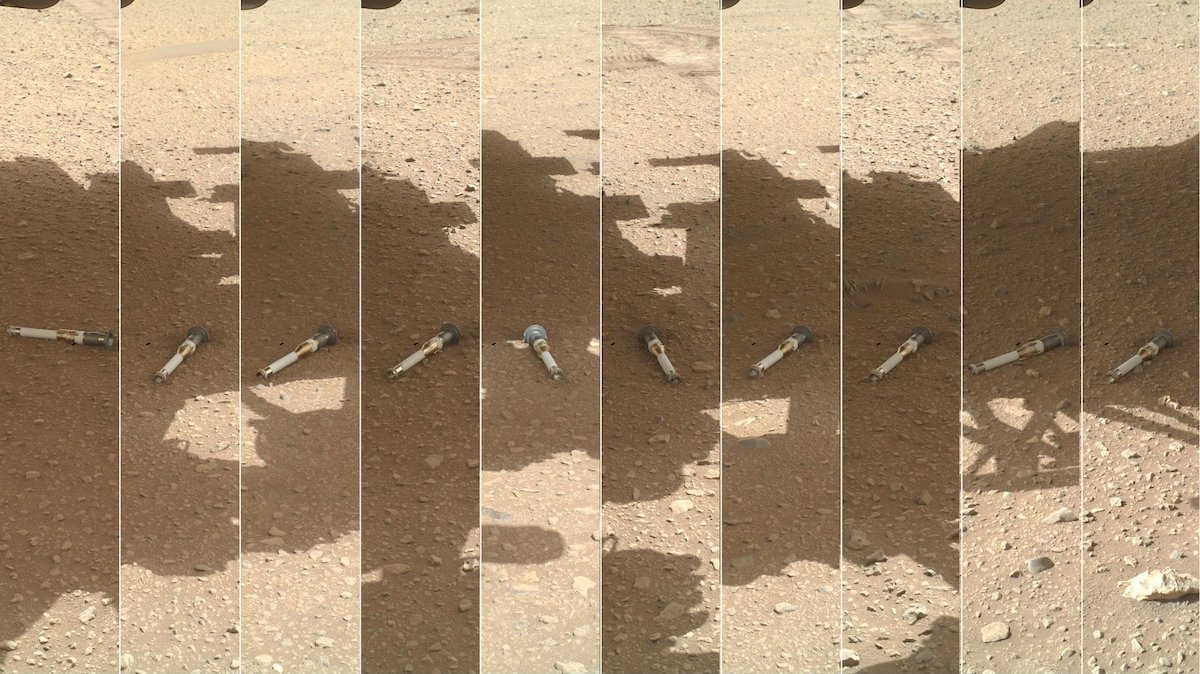

Through its Mars Sample Return Program, NASA has for more than two decades been inching toward the goal of retrieving samples of Martian soil that NASA’s Perseverance rover has been collecting since 2021. To do that, the agency had been working to develop multiple new spacecraft to relay the samples off the Martian surface and fly them back to Earth.

NASA said in its announcement it is changing the plan for the spacecraft that will land on Mars to retrieve the samples and exploring two new, different options.

One of the options is to attempt a style of landing similar to what NASA successfully executed with the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers. As each rover made its descent, rockets were fired to slow the spacecraft, and an intricate sky crane then lowered them to the Martian surface.

The second option would be to work with private space companies to send a new lander to Mars.

NASA plans to pursue both possibilities in tandem before it makes a final decision about which to use in 2026.

Space industry experts had speculated for months about the fate of the Mars Sample Return Program, which has fallen behind schedule as its budget has swelled.

“The cost began to accelerate to the point that earlier this past year, it was thought that it could be as much as $11 billion, and you would not even get the samples back until 2040,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said at a news briefing Tuesday. “That was just simply unacceptable.”

NASA’s original plan called for developing a “sample retrieval lander,” which would have been equipped with two helicopters to retrieve the sealed sample tubes of rock, soil and atmosphere that Perseverance has collected and cached. The lander would also have carried a rocket to launch the samples off the Martian surface.

Perseverance, which touched down in 2021, has been exploring a 28-mile-wide basin north of the Martian equator that scientists think was home to an ancient river delta.

NASA's earlier plan called for the helicopters to gather the rover's samples, after which the lander’s robotic arm would load them into the rocket. Then the rocket would blast off the Martian surface and jettison a capsule containing the samples while it was in orbit around the planet.

After that would come yet another cosmic relay: The capsule would be intercepted by a spacecraft designed by the European Space Agency, and the precious cargo would begin a journey to Earth.

The details of the design for a different lander and how it would gather the samples once it is on Mars are not yet clear. NASA said, however, that both of the new options involve a smaller rocket system to blast off the Martian surface.

The two alternatives would still use the European-developed vehicle for the journey back to Earth.

Nelson said the changes to NASA's plan could allow samples to arrive back on Earth as early as 2035, but he added that, depending on NASA funding, the timeline could extend to 2039.

He said that the sky crane option would be likely to cost $6.6 billion to $7.7 billion and that the commercial route would be likely to cost $5.8 billion to $7.1 billion.

NASA officials emphasized the importance of studying the samples.

“Mars Sample Return will allow scientists to understand the planet’s geological history and the evolution of climate on this barren planet where life may have existed in the past and shed light on the early solar system before life began here on Earth,” Nicky Fox, head of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said in a statement. “This will also prepare us to safely send the first human explorers to Mars.”

However, NASA has faced scrutiny in recent years over the cost and timing of several of its biggest programs, including the Mars Sample Return initiative and the Artemis return-to-the-moon program.

The United States also faces increased competition from China, which has made rapid advancements in its space program over the past decade. Last year, China became the first country to collect and return samples from the far side of the moon, and Chinese officials have said they intend to launch a mission to retrieve samples from Mars and return them to Earth by around 2031.

Nelson, however, said that NASA’s plan is more intricate than what Chinese officials have spoken about publicly and that the U.S. program is centered on answering fundamental questions about Mars’ history, rather than being driven by a space race.

“You cannot compare the two missions,” he said. “Will people say that there’s a race? Well, of course people will say that. But it’s two totally different missions.

Quelle: NBC News

----

Update: 7.02.2025

.

Missing link still needed to save Mars Sample Return

An illustration of the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) that will transport gathered Martian samples from the surface to orbit, where it will rendezvous with another spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

There is a perception that NASA’s Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission is being delayed by indecision, but the real delay has been multiple decades of seeking a heritage propulsion solution instead of a technology advance to develop and test a Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) for launching the samples to Mars orbit. Imagine needing a sophisticated Mars rover in the absence of JPL’s core team of engineers with their decades of specialized design and testing. Now a MAV is needed, absent any comparable cadre of expertise for miniature launch vehicles. The MAV remains a wildcard for MSR, possibly even a hot potato, because there is no experience base for making such a rocket small enough to deliver to Mars within a science mission budget. There are no other customers to stimulate investment for something like a MAV, and there is no established peer review system for technical guidance.

It seems worthy of concern that rocket engineering has not been represented among MSR advisory committees and decision makers including the MSR Standing Review Board, Planetary Decadal Survey committees, the second MSR Independent Review Board (IRB-2 in 2023), and the MSR hierarchy within the NASA Science Mission Directorate. It is not surprising that MAV expertise is underrepresented, because the available talent pool at the top of the org chart comes from planetary and other space science missions, and Earth satellite programs. These highly experienced spacecraft systems engineers and managers have always enjoyed the availability of proven propulsion technology for maneuvers that are far easier than Mars departure. Therefore, MAV development has been consistently underestimated.

Given that MAV success is mission-critical, NASA planning documents circa 2010 called for successful flight testing of a MAV over Earth, prior to preliminary design review for MSR. By 2020, that requirement had vanished from mission planning, as though launching from Mars is just another propulsive maneuver for a spacecraft. Spacecraft propulsion has built-in redundancy, while launch vehicles are far less fault tolerant. Unlike launching from Earth, the MAV will not enjoy the luxury of a team on the ground for pre-launch repairs and adjustments, which raises the bar for reliability. That bar is raised even higher by NASA’s expectation of placing all 30 sample tubes on the one-and-only MAV departure from Mars.

In October 2020, the report to NASA from the first MSR Independent Review Board (IRB-1) explained the underlying MAV challenge, noting that “the smaller a launch vehicle, the more sensitive its dry mass to design uncertainty.” Variations in the dry mass are amplified at least five times for the total MAV mass, considering that propellant mass approaches 80% of the whole MAV. Some originality in engineering is needed to make all the parts unusually lightweight relative to the propellant mass and thrust, so a sufficiently small MAV might be considered new technology.

The membership of MSR IRB-1 included Antonio Elias, a seasoned rocket engineer who presided over development of the Pegasus small launch vehicle in the 1980s. In December 2020, he explained in a public meeting of the National Academies’ Planetary Decadal Survey that it is generally not possible to dictate both the mass of a launch vehicle and the mass of its payload in advance of completing design and testing, with some iteration and refinement. Hence the goal to accommodate all 30 sample tubes leaves the total MAV mass uncertain.

In 2022, the Planetary Decadal final report set the highest priority for MSR, but made no mention of the wisdom from Elias. The publication, “Origins, Worlds, and Life,” refers to the MAV in only one place, and moreover says that it would be accompanied by a European sample-fetch rover, later abandoned due to payload mass limits. Appendix B of the Decadal report lists my own submissions from 2020 about the MAV, which noted the need for a sustained effort beyond design-buildengineering, explained 25 misconceptions, and described options for implementing launch vehicle design principles on a miniature scale.

On April 15, 2024, NASA announced a competition for “Rapid Mission Design Studies” in search of cost and schedule improvements for completing MSR. That news emphasized hopes for a smaller MAV derived from heritage technology, subsequently a key consideration for a dozen studies done over the summer. In a Jan. 7, 2025 news conference, little was said about fresh ideas for a smaller MAV, despite the many proposals submitted. Instead, NASA officials explained that two options will now be considered for the sample retrieval lander needed to deliver the MAV. As reported in SpaceNews, the delivery alternatives are the heritage “sky crane” from JPL, or a commercially provided “heavy lander.” The implicit message is that options will now be considered for delivering a heavier MAV if it cannot be made small.

Ideally, the MAV can be 350 kilograms or less for delivery by JPL, while a heavy lander would be needed for a large MAV. Support equipment for the MAV and other essentials will ride along, respectively raising the total landed mass to roughly a ton or potentially well over one ton.

Reaching Mars orbit from the surface requires a propulsive capability way beyond all previous experience for spacecraft maneuvers, approximately 4,000 meters per second in a few minutes. Some spacecraft can produce this velocity change, but way too gradually. As I told the Mars science community in a July 2024 presentation, the planned solid-propellant MAV could reach a thousand miles if flight tested over Earth, starting at a high altitude where the air is as thin as the Mars atmosphere. Such a flight path has never been done by any missile smaller than a ton.

The January 2025 news conference briefly referred to the two-stage solid propellant MAV that NASA has been planning. Technical details were most recently published by the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in early 2022, before Lockheed-Martin was brought on board to help. The MSFC authors described remaining challenges with the design, including aerodynamic complexities during first stage flight, the location of steering thrusters close to the center of mass, and the possibility of tip-off rotation at stage separation. They wrote that it would be ideal to flight test a complete prototype MAV over Earth, but that the cost would be high.

The combination of first stage aerodynamic complexities and low leverage for steering thrusters suggests a risk of prematurely running out of steering propellant in the absence of flight testing to fully understand vehicle dynamics and verify margins. To reduce mass, the upper stage is to be spin-stabilized instead of actively guided, a design change made public early in 2021. Additionally for mass reduction and contrary to the 2010-era documents, the upper stage might not have telemetry, hence “no data” if imperfect spinning slips past stability margins to become a mission-ending tumble.

Now that Lockheed is working on the MAV, it is notable that in 2001 the company told NASA that a flight demonstration over Earth would be needed, while only testing MAV parts separately as done for spacecraft propulsion would mean a high risk of mission failure. In a 2012 publication, Lockheed wrote that “a systematic systems engineering process” would lead to a high-heritage low-risk MAV under 300 kg. Contractors sometimes need to say what customers want to hear.

China plans to do MSR using Long March 5 launches from Earth, which can send more mass toward Mars than the Atlas 5 that launched Perseverance. The difference is consistent with a heavier Mars lander than the JPL sky crane, hence a relatively heavy MAV. Larger objects slow down less readily in the thin Mars atmosphere, necessitating some degree of new technology for Mars arrival. Ten years ago, NASA studied options for deployable or inflatable aerodynamic decelerators followed by supersonic retropropulsion, using capabilities from Blue Origin and SpaceX. Implementing MSR with a heavy lander and a larger MAV would be a worthy step toward scaling up to human missions, deserving of some Artemis funds for MSR.

Rock core samples are now waiting on Mars, but the status of MAV development has changed little over more than two decades. It might help to begin open engineering discussions akin to public science discussions, and for rocket engineering expertise to be elevated to a higher position on the MSR org chart. Perhaps the MAV needs a glamorous name, to be publicized as “the most amazing little rocket ever built.”

John Whitehead, PhD is a former rocket technology researcher. His 2008 paper, “Defining the Mars Ascent Problem for Sample Return” explained that developing a MAV is both a daunting technical problem and a cultural challenge for the planetary science community

Quelle: SN