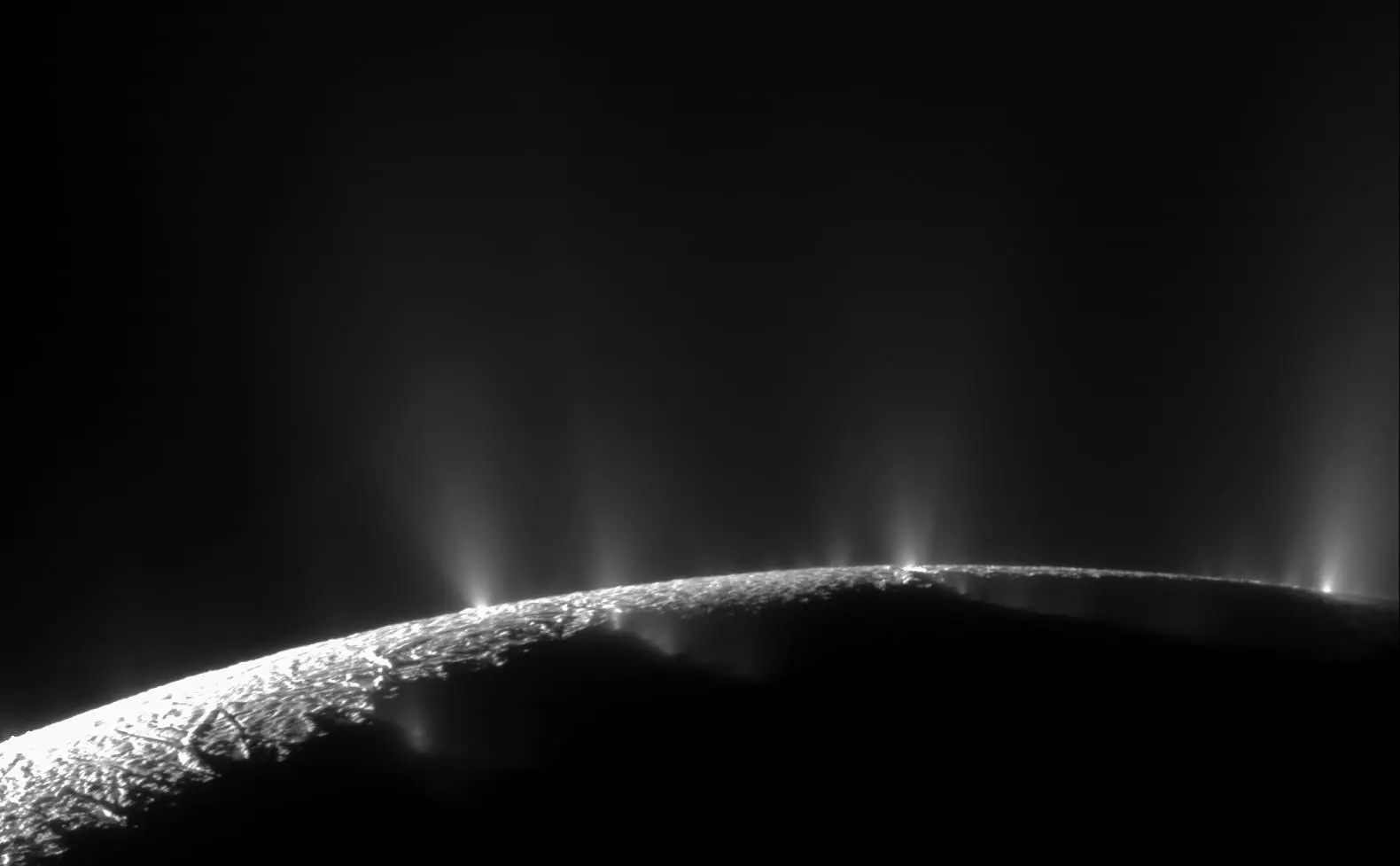

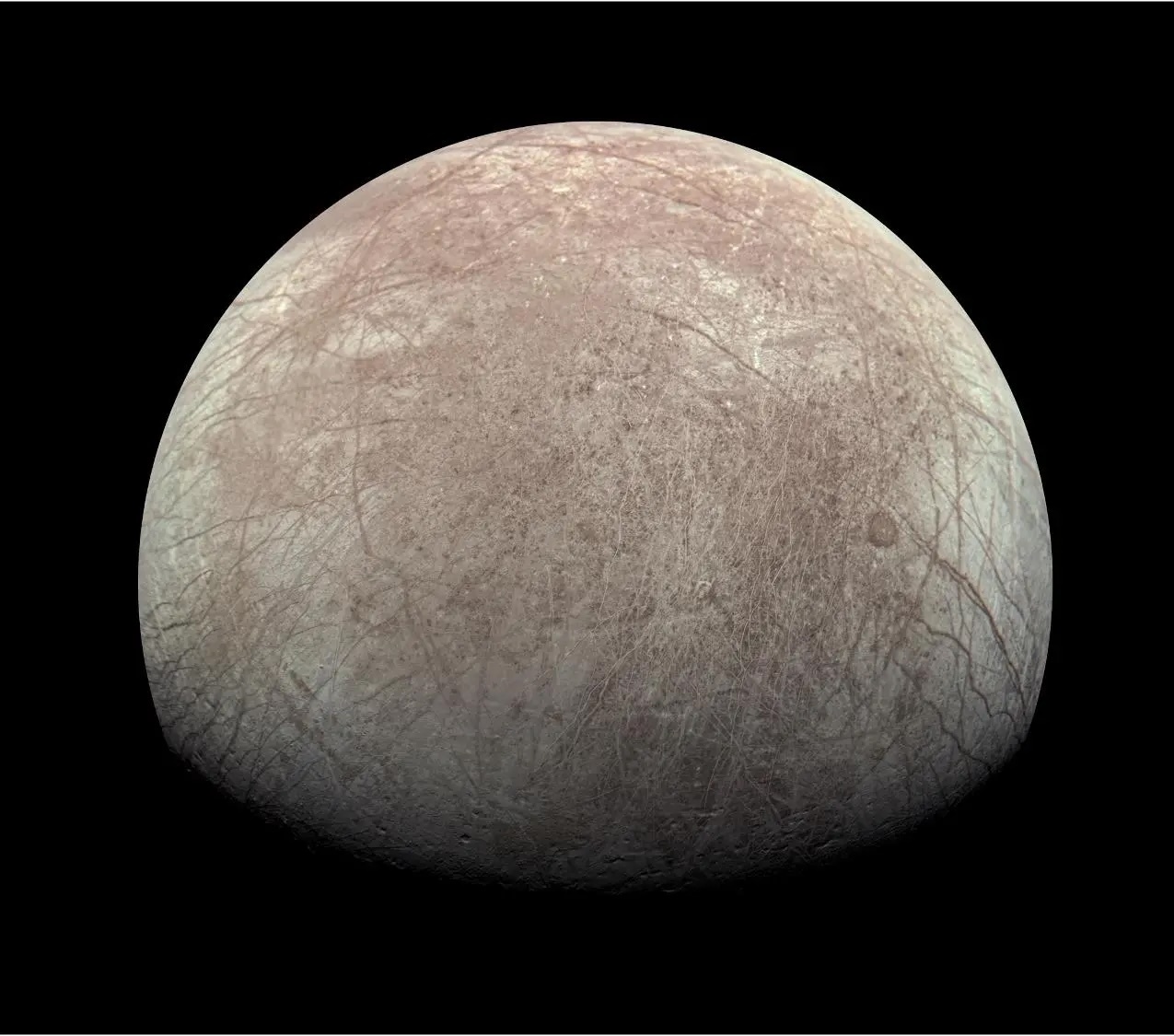

Europa, a moon of Jupiter, and Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, have evidence of oceans beneath their ice crusts. A NASA experiment suggests that if these oceans support life, signatures of that life in the form of organic molecules (e.g. amino acids, nucleic acids, etc.) could survive just under the surface ice despite the harsh radiation on these worlds. If robotic landers are sent to these moons to look for life signs, they would not have to dig very deep to find amino acids that have survived being altered or destroyed by radiation.

20.07.2024

“Based on our experiments, the ‘safe’ sampling depth for amino acids on Europa is almost 8 inches (around 20 centimeters) at high latitudes of the trailing hemisphere (hemisphere opposite to the direction of Europa’s motion around Jupiter) in the area where the surface hasn’t been disturbed much by meteorite impacts,” said Alexander Pavlov of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, lead author of a paper on the research published July 18 in Astrobiology. “Subsurface sampling is not required for the detection of amino acids on Enceladus – these molecules will survive radiolysis (breakdown by radiation) at any location on the Enceladus surface less than a tenth of an inch (under a few millimeters) from the surface.”

The frigid surfaces of these nearly airless moons are likely uninhabitable due to radiation from both high-speed particles trapped in their host planet’s magnetic fields and powerful events in deep space, such as exploding stars. However, both have oceans under their icy surfaces that are heated by tides from the gravitational pull of the host planet and neighboring moons. These subsurface oceans could harbor life if they have other necessities, such as an energy supply as well as elements and compounds used in biological molecules.

The experiments provided pivotal data to determine the rates at which amino acids break down, called radiolysis constants. With these, the team used the age of the ice surface and the radiation environment at Europa and Enceladus to calculate the drilling depth and locations where 10 percent of the amino acids would survive radiolytic destruction.

Although experiments to test the survival of amino acids in ice have been done before, this is the first to use lower radiation doses that don’t completely break apart the amino acids, since just altering or degrading them is enough to make it impossible to determine if they are potential signs of life. This is also the first experiment using Europa/Enceladus conditions to evaluate the survival of these compounds in microorganisms and the first to test the survival of amino acids mixed with dust.

The team found that amino acids degraded faster when mixed with dust but slower when coming from microorganisms.

“Slow rates of amino acid destruction in biological samples under Europa and Enceladus-like surface conditions bolster the case for future life-detection measurements by Europa and Enceladus lander missions,” said Pavlov. “Our results indicate that the rates of potential organic biomolecules’ degradation in silica-rich regions on both Europa and Enceladus are higher than in pure ice and, thus, possible future missions to Europa and Enceladus should be cautious in sampling silica-rich locations on both icy moons.”

A potential explanation for why amino acids survived longer in bacteria involves the ways ionizing radiation changes molecules -- directly by breaking their chemical bonds or indirectly by creating reactive compounds nearby which then alter or break down the molecule of interest. It’s possible that bacterial cellular material protected amino acids from the reactive compounds produced by the radiation.

The research was supported by NASA under award number 80GSFC21M0002, NASA’s Planetary Science Division Internal Scientist Funding Program through the Fundamental Laboratory Research work package at Goddard, and NASA Astrobiology NfoLD award 80NSSC18K1140.

Quelle: NASA