.

Dogs have been man’s best friend for tens of thousands of years. Their superior tracking abilities, combined with man’s superior killing abilities, made them invaluable to early hunter-gatherers.

This relationship persists to today, but the apex of the bond of friendship between the two species may have come in 1957, when a three-year-old mongrel named Kudryavka (“Little Curly”) was picked up on the streets of Moscow. She weighed about six kilograms, was part husky and part terrier, and had survived through several harsh Russian winters.

That made her the perfect candidate for an experimental programme being run by the Soviet government. Vladimir Yazdovsky was a medical scientist in the space program, who’d launched a number of dogs to altitudes of more than 450km in pressurised rockets.

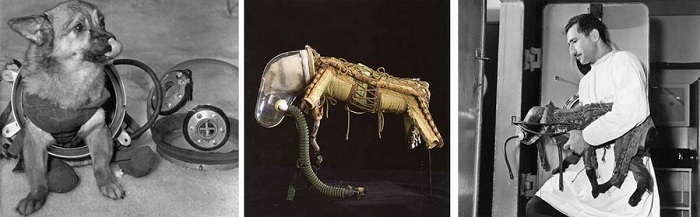

While the US test rocket programme used monkeys, about two thirds of whom died, dogs were chosen by the Soviets for their ability to withstand long periods of inactivity, and were trained extensively before they flew. Only stray female dogs were used because it was thought they’d be better able to cope with the extreme stress of spaceflight, and the bubble-helmeted spacesuits designed for the programme were equipped with a device to collect feces and urine that only worked with females.

Training included standing still for long periods, wearing the spacesuits, being confined in increasingly small boxes for 15-20 days at a time, riding in centrifuges to simulate the high acceleration of launch, and being placed in machines that simulated the vibrations and loud noises of a rocket.

.

Some of the spacesuit designs used by the canine cosmonats // National Space Centre

.

The first pair of dogs to travel to space were Dezik and Tsygan (“Gypsy”), who made it to 110km on 22 July 1951 and were recovered, unharmed by their ordeal, the next day. Dezik returned to space in September 1951 with a dog named Lisa, but neither survived the journey. After Dezik’s death, Tsygan was adopted by Anatoli Blagronravov, a physician who later worked closely with the United States at the height of the Cold War to promote international cooperation on spaceflight.

They were followed by Smelaya (“Brave”), who defied her name by running away the day before her launch was scheduled. She was found the next morning, however, and made a successful flight with Malyshka (“Babe”). Another runaway was Bolik, who successfully escaped a few days before her flight in September 1951. Her replacement was ignomoniously named ZIB — the Russian acronym for “Substitute for Missing Bolik”, and was a street dog found running around the barracks where the tests were being conducted. Despite being untrained for the mission, he made a successful flight and returned to Earth unharmed.

“Despite being untrained for the mission, he made a successful flight and returned to Earth unharmed.”

In June 1954, Another dog named Lisa flew to an altitude of 100km with a companion named Ryzhik (“Ginger”), returning successfully. But they didn’t have to deal with the trauma of a mid-air ejection at an altitude of 85km, as Albina and Tsyganka (“Gypsy Girl”) did. The pair landed safely, and it was noted in particular by the scientists how well Albina had coped with the journey.

.

In 1957, Soviet scientists were ready to attempt something rather more audacious — an orbital flight. Sputnik was launched on 4 October 1957, in a storm of publicity, sparking something of a crisis in the United States. This triggered the space race, and eventually led not only to the creation of NASA and eventually the Apollo programme and Moon landings, but also a vast increase in the funding of science.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, in full thaw, decided to increase that pressure on the US and so Sputnik was followed up a mere month later by Sputnik 2 — a mission to put a living creature into orbit. The Soviets didn’t have the time to build the technology to bring the craft back, so it was known from the start that whichever animal was chosen would perish in space.

A longlist of ten canine cosmonauts was drawn up, which was then reduced to a shortlist of three. They were Albina — who’d already ejected from 85km, a dog named Mushka (“Little Fly”), and the aforementioned Kudryavka, who’d been collected on the streets of Moscow and impressed her trainers with her calm and quiet demeanour in the face of simulated stresses.

That even temperament won her the honour of being the first animal in orbit, and she was renamed Laika (“Barker”). In the days before launch she was kept in the module she would fly in — it was padded, had enough room for her to stand or lie down as she wanted to, and gave her access to a specially-designed nutritious jelly that was high in fibre for her to eat.

.

Dogs were housed in padded boxes like this for their voyage, allowing them space to stand or sit, and giving them access to food.

.

Before launch, she was covered in an alcohol solution and painted with iodine in the places where sensors were connected to her skin, which monitored her heartbeat, blood pressure and other biological variables.

On 3 November 1957, Laika blasted off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome and became the first creature to orbit the Earth. The launch went smoothly, and her capsule entered an elliptical orbit, circling the planet at 29,000 km/h and completing a full rotation every hour and forty-two minutes.

While Laika certainly made it into space alive, it’s not entirely clear how long she lived after that. It was originally announced that she was euthanised with poisoned food several days into the mission, then it was said she died when her oxygen supply ran out, on the sixth day of her journey.

.

Laika on a Romanian postage stamp

.

But in October 2008, fifty-one years after her journey and after a monument had been erected in her honour near the facility in which she was trained, it was finally revealed that she had most likely perished a few hours after launch from overheating and stress caused by the failure of a rocket component to separate from the capsule.

“We did not learn enough from this mission to justify the death of the dog.”

Oleg Gazenko, one of the scientists working on the mission, said in 1998 that he regretted sending Laika to her death:

Work with animals is a source of suffering to all of us. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We shouldn’t have done it… We did not learn enough from this mission to justify the death of the dog.

.

Laika in training and her memorial in Moscow // Soviet Space Program

.

But the mission was another great success for the Soviets, and the space programme continued. One of the most-travelled dogs was named Otvazhnaya (“Brave One”), who accompanied a dog named Snezhinka (“Snowflake”) into sub-orbital space on 2 July 1959 before making five more successful flights that year.

On 28 July 1960, Bars (“Snow Leopard”) and Lisichka (“Little Fox”) were chosen to follow Laika into orbit, but both perished after their rocket explosively disintegrated just twenty-eight seconds into the launch sequence. This crash caused considerable uproar within the Soviet space programme, as the problem that caused the explosion had supposedly been fixed.

Belka (“Squirrel”) and Strelka (“Arrow”) were the next successful orbiters, spending a day in space on 19 August 1960 aboard Sputnik 5, which was a veritable Noah’s Ark of animals. The craft contained Belka, Strelka, a grey rabbit, forty-two mice, two rats, flies, and several plants and fungi, as well as some slightly creepy strips of human flesh.

All the animals survived the spacecraft’s return to Earth on 20 August, though telemetry showed that one of the dogs had suffered a seizure during the fourth orbit. That led directly to the decision to limit Yuri Gagarin’s legendary flight the following year to just three orbits before returning to Earth.

Strelka subsequently had six puppies with Pushok, a male dog kept around the research base, who participated in many of the ground-based experiments but didn’t travel to space. One of the puppies was named Pushinka (“Fluffy”) and was given to US president John F Kennedy’s daughter, Caroline, by Khrushchev in 1961.

The dog was initially kept away from the White House by Kennedy’s staff over fear that its body may have been implanted with microphones, but after a medical check she was brought into the home and won the heart of another of Kennedy’s dogs — a Welsh Terrier named Charlie. They had a litter of puppies together themselves, which Kennedy affectionately referred to as “pupniks”. Their descendents are still living today, and Belka and Strelka were celebrated in 2010 with an animated feature film named Space Dogs.

.

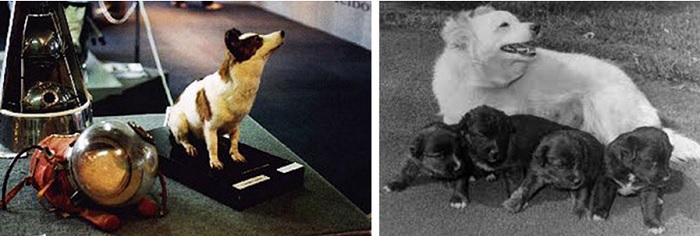

Left: A model of Strelka in Australia in 1993 // Right: Pushinka and her pupniks

.

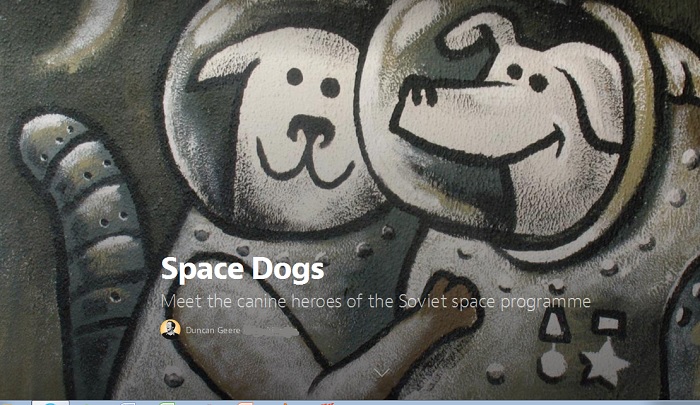

On 1 December 1960, tragedy struck. Mushka — who was shortlisted for Laika’s mission but lost out after — finally made it into space aboard Sputnik 6, accompanied by Pchyolka (“Little Bee”) and other animals, plants and insects. They were in good health when the rocket began its re-entry, but at the last minute a navigation error meant that the craft would have landed outside of Soviet borders.

.

The CIA intercepted and decoded this image of one of the dogs aboard Sputnik 6 in December 1960

.

Fear of foreign agents inspecting the capsule trumped the lives of the dogs aboard the spacecraft, and so it was intentionally destroyed, killing everything aboard.

On 22 December 1960, the team tried once more. Damka (“Queen of Checkers”) and Krasavka (“Little Beauty”) were selected from the pool and prepared for launch.

Almost immediately after taking off, however, the rocket encountered difficulties. The upper stage booster failed, causing the craft to re-enter the atmosphere after reaching a maximum altitude of 214km. The back-up plan in this situation was to eject the dogs and then self-destruct, but the ejector seat failed to operate, leaving the dogs stuck in the capsule as the self-destruct sequence ticked down.

Then something incredible happened. The self-destruct module also shorted out — aborting the sequence, and the capsule plummeted back to Earth intact, landing in deep snow in Siberia. A backup self-destruct timer had been set for 60 hours, so a team was scrambled to quickly locate the craft. They found it on the first day, but without sufficient daylight to disarm the self-destruct sequence and open the capsule. They were only able to report that the window of the capsule had frosted over in the -45C temperatures of the landing site, and no signs of life were heard from inside.

The next day, at dawn, they returned to the capsule fearing the worst. As it was opened, however, barking was heard — Damka and Krasavka were alive, though the mice that had accompanied them on the mission had frozen to death in the freezing temperatures of Siberia.

The dogs were wrapped in sheepskin coats immediately, and flown to Moscow, where they were thawed out and given the best medical care. Both survived, and Krasavka was adopted by Oleg Gazenko, a Lieutenant General who’d fought in World War II and the Korean War, and supervised the mission. Krasavka went on to have a litter of puppies, before dying at home 14 years later.

.

Damka and Krasavka narrowly escaped tragedy, before living long and healthy lives.

.

As the Soviet spaceflight programme ramped up towards its first human launch in 1961, the dogs began to be accompanied by dummy cosmonauts.

Chernushka (“Blackie”) flew on Sputnik 9 on 9 March 1961 with a dummy named Ivan Ivanovich, some mice and a guinea pig. To test the spacecraft communications, they placed a recording of a choir in Ivanovich’s chest, so that any radio stations picking up the signal would understand he wasn’t real. He was ejected at altitude, and parachuted to the ground, while Chernushka was recovered unharmed from the capsule.

Zvyozdochka (“Starlet”, named by Gagarin himself) flew on Sputnik 10 on the final practice flight before Gagarin’s voyage on 25 March 1961, again accompanied by Ivanovich and his choir recording — which this time had been augmented with a recipe for cabbage soup to confuse anyone listening in. Again, both the dummy and the dog returned safely to Earth, and Ivanovich was auctioned in 1993 for $189,500, still in his spacesuit. Today he lives in the US National Air and Space museum.

.

Ugolyok and Veterok in space. 1966

.

Following Gagarin’s triumphant mission on 12 April 1961, the Soviets slowly dismantled their dogs-in-space programme as it was no longer required. Its final flight, the Cosmos 110 mission, came five years later on 22 February 1966. It carried two dogs — Veterok (“Light Breeze”) and Ugolyok (“Coal”), who spent a record-breaking 22 days in orbit, testing whether life could survive for longer durations in orbit. As well as Veterok and Ugolyok, it carried yeast cells, blood cells and live bacteria.

The long-duration mission was a success, and the dogs were safely landed back on Earth. However, in their medical checkups afterward, it was discovered that their muscle and bone structures had sustained some damage from spending such a long time zero gravity, paving the way for later discoveries on the biological effects of spaceflight on the human body. Veterok and Ugolyok held the record for spaceflight duration until Skylab 2 in 1973, and still hold the record for the longest spaceflight by dogs.

A number of other dogs flew on sub-orbital flights, including Dymka (“Smoky”), Modnitsa (“Fashionable”) and Kozyavka (“Little Gnat”), as well as at least four others whose names don’t survive to this day. Almost all survived, with the exception of two of the unnamed dogs who perished in failed launches.

Without their contributions, and those of their canine colleagues, Russia would never have been able to launch Sputnik in 1957 and Gagarin in 1961, and the space race may never have taken off. Their heroism and bravery fuelled the earliest space exploration missions, paving the way for humans to later follow.

So to Dezik and Tsygan, Smelaya, Malyshka, ZIB, Ryzhik, Albina and Tsyganka, Mushka, Otvazhnaya, and Snezhunka, Bars and Lisichka, Belka and Strelka, Pushok, Pchyolka, Damka and Krasavka, Chernushka, Zvyozdochka, Veterok and Ugolyok, Dymka, Modnitsa, Kozyavka — and, most of all, Laika — I’d like to thank you for everything that you’ve done for mankind.

Хорошая собака, or as we say in the West…

Good dog.Quelle: