14.06.2024

Researchers are diving into a synthetic universe to help us better understand the real one. Using supercomputers at the U.S. DOE’s (Department of Energy’s) Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois, scientists have created nearly 4 million simulated images depicting the cosmos as NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, jointly funded by NSF (the National Science Foundation) and DOE, in Chile will see it.

Michael Troxel, an associate professor of physics at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, led the simulation campaign as part of a broader project called OpenUniverse. The team is now releasing a 10-terabyte subset of this data, with the remaining 390 terabytes to follow this fall once they’ve been processed.

“Using Argonne’s now-retired Theta machine, we accomplished in about nine days what would have taken around 300 years on your laptop,” said Katrin Heitmann, a cosmologist and deputy director of Argonne’s High Energy Physics division who managed the project’s supercomputer time. “The results will shape Roman and Rubin’s future attempts to illuminate dark matter and dark energy while offering other scientists a preview of the types of things they’ll be able to explore using data from the telescopes.”

A Cosmic Dress Rehearsal

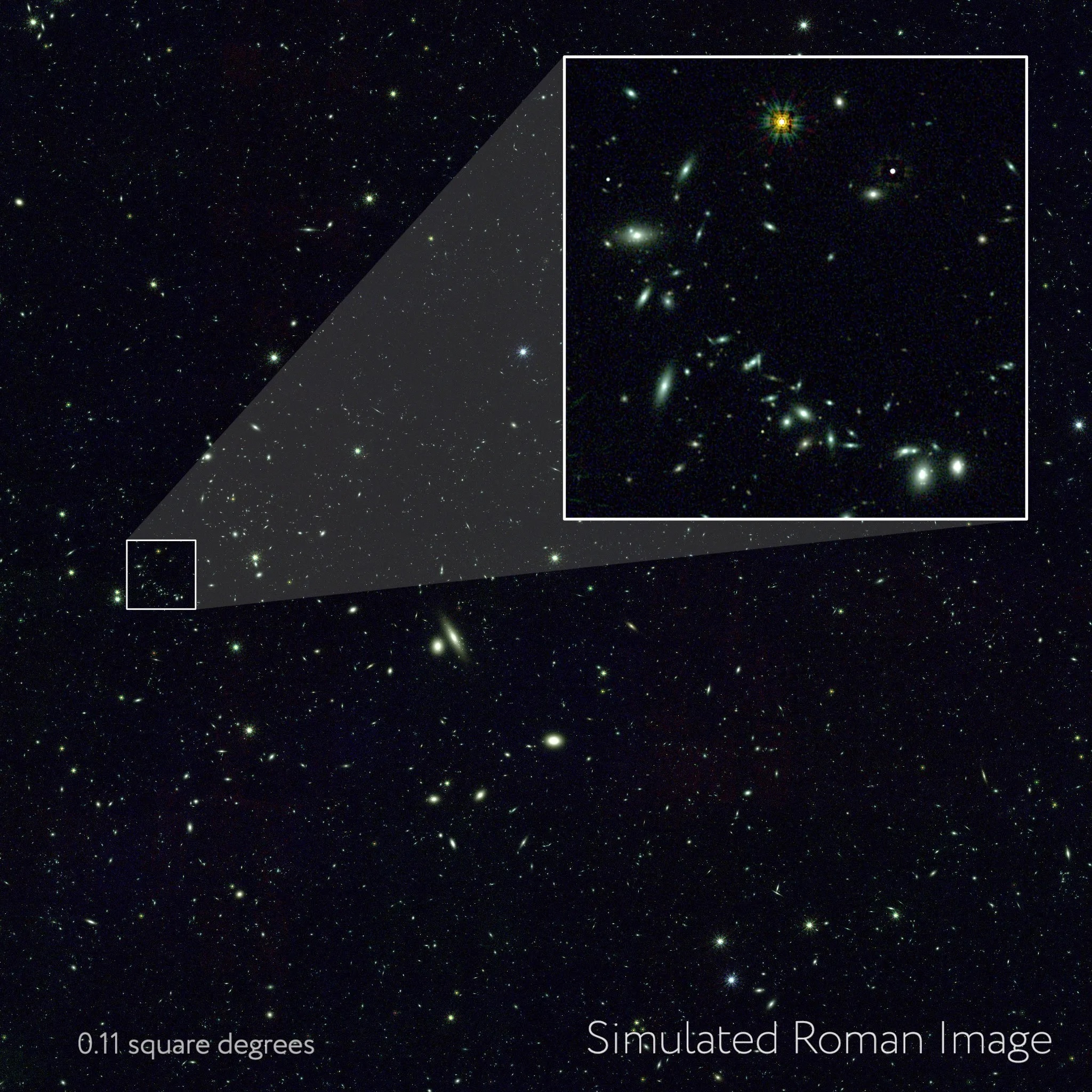

For the first time, this simulation factored in the telescopes’ instrument performance, making it the most accurate preview yet of the cosmos as Roman and Rubin will see it once they start observing. Rubin will begin operations in 2025, and NASA’s Roman will launch by May 2027.

The simulation’s precision is important because scientists will comb through the observatories’ future data in search of tiny features that will help them unravel the biggest mysteries in cosmology.

Roman and Rubin will both explore dark energy –– the mysterious force thought to be accelerating the universe’s expansion. Since it plays a major role in governing the cosmos, scientists are eager to learn more about it. Simulations like OpenUniverse help them understand signatures that each instrument imprints on the images and iron out data processing methods now so they can decipher future data correctly. Then scientists will be able to make big discoveries even from weak signals.

“OpenUniverse lets us calibrate our expectations of what we can discover with these telescopes,” said Jim Chiang, a staff scientist at DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, California, who helped create the simulations. “It gives us a chance to exercise our processing pipelines, better understand our analysis codes, and accurately interpret the results so we can prepare to use the real data right away once it starts coming in.”

Then they’ll continue using simulations to explore the physics and instrument effects that could reproduce what the observatories see in the universe.

Telescopic Teamwork

It took a large and talented team from several organizations to conduct such an immense simulation.

“Few people in the world are skilled enough to run these simulations,” said Alina Kiessling, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California and the principal investigator of OpenUniverse. “This massive undertaking was only possible thanks to the collaboration between the DOE, Argonne, SLAC, and NASA, which pulled all the right resources and experts together.”

And the project will ramp up further once Roman and Rubin begin observing the universe.

“We’ll use the observations to make our simulations even more accurate,” Kiessling said. “This will give us greater insight into the evolution of the universe over time and help us better understand the cosmology that ultimately shaped the universe.”

The Roman and Rubin simulations cover the same patch of the sky, totaling about 0.08 square degrees (roughly equivalent to a third of the area of sky covered by a full Moon). The full simulation to be released later this year will span 70 square degrees, about the sky area covered by 350 full Moons.

Overlapping them lets scientists learn how to use the best aspects of each telescope –– Rubin’s broader view and Roman’s sharper, deeper vision. The combination will yield better constraints than researchers could glean from either observatory alone.

“Connecting the simulations like we’ve done lets us make comparisons and see how Roman’s space-based survey will help improve data from Rubin’s ground-based one,” Heitmann said. “We can explore ways to tease out multiple objects that blend together in Rubin’s images and apply those corrections over its broader coverage.”

Scientists can consider modifying each telescope’s observing plans or data processing pipelines to benefit the combined use of both.

“We made phenomenal strides in simplifying these pipelines and making them usable,” Kiessling said. A partnership with Caltech/IPAC’s IRSA (Infrared Science Archive) makes simulated data accessible now so when researchers access real data in the future, they’ll already be accustomed to the tools. “Now we want people to start working with the simulations to see what improvements we can make and prepare to use the future data as effectively as possible.”

OpenUniverse, along with other simulation tools being developed by Roman’s Science Operations and Science Support centers, will prepare scientists for the large datasets expected from Roman. The project brings together dozens of experts from NASA’s JPL, DOE’s Argonne, IPAC, and several U.S. universities to coordinate with the Roman Project Infrastructure Teams, SLAC, and the Rubin LSST DESC (Legacy Survey of Space and Time Dark Energy Science Collaboration). The Theta supercomputer was operated by the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility, a DOE Office of Science user facility.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is managed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, with participation by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Caltech/IPAC in Southern California, the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, and a science team comprising scientists from various research institutions. The primary industrial partners are BAE Systems, Inc. in Boulder, Colorado; L3Harris Technologies in Rochester, New York; and Teledyne Scientific & Imaging in Thousand Oaks, California.

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory is a federal project jointly funded by the National Science Foundation and the DOE Office of Science, with early construction funding received from private donations through the LSST Discovery Alliance.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 27.07.2024

.

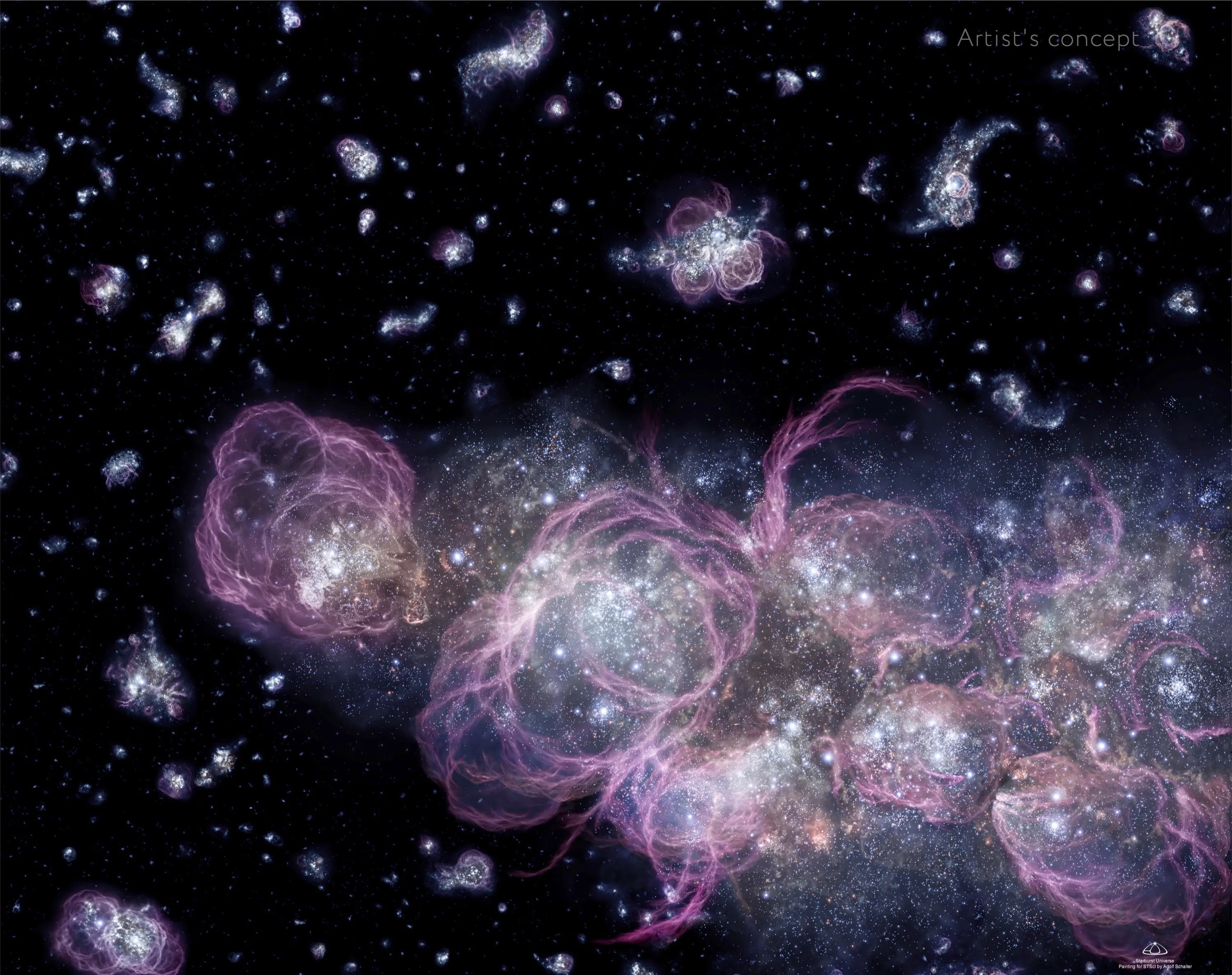

Today, enormous stretches of space are crystal clear, but that wasn’t always the case. During its infancy, the universe was filled with a “fog” that made it opaque, cloaking the first stars and galaxies. NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will probe the universe’s subsequent transition to the brilliant starscape we see today –– an era known as cosmic dawn.

“Something very fundamental about the nature of the universe changed during this time,” said Michelle Thaller, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Thanks to Roman’s large, sharp infrared view, we may finally figure out what happened during a critical cosmic turning point.”

Lights Out, Lights On

Shortly after its birth, the cosmos was a blistering sea of particles and radiation. As the universe expanded and cooled, positively charged protons were able to capture negatively charged electrons to form neutral atoms (mostly hydrogen, plus some helium). That was great news for the stars and galaxies the atoms would ultimately become, but bad news for light!

It likely took a long time for the gaseous hydrogen and helium to coalesce into stars, which then gravitated together to form the first galaxies. But even when stars began to shine, their light couldn’t travel very far before striking and being absorbed by neutral atoms. This period, known as the cosmic dark ages, lasted from around 380,000 to 200 million years after the big bang.

Then the fog slowly lifted as more and more neutral atoms broke apart over the next several hundred million years: a period called the cosmic dawn.

“We’re very curious about how the process happened,” said Aaron Yung, a Giacconi Fellow at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, who is helping plan Roman’s early universe observations. “Roman’s large, crisp view of deep space will help us weigh different explanations.”

Prime Suspects

It could be that early galaxies may be largely to blame for the energetic light that broke up the neutral atoms. The first black holes may have played a role, too. Roman will look far and wide to examine both possible culprits.

“Roman will excel at finding the building blocks of cosmic structures like galaxy clusters that later form,” said Takahiro Morishita, an assistant scientist at Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena, California, who has studied cosmic dawn. “It will quickly identify the densest regions, where more ‘fog’ is being cleared, making Roman a key mission to probe early galaxy evolution and the cosmic dawn.”

The earliest stars were likely starkly different from modern ones. When gravity began pulling material together, the universe was very dense. Stars probably grew hundreds or thousands of times more massive than the Sun and emitted lots of high-energy radiation. Gravity huddled up the young stars to form galaxies, and their cumulative blasting may have once again stripped electrons from protons in bubbles of space around them.

“You could call it the party at the beginning of the universe,” Thaller said. “We’ve never seen the birth of the very first stars and galaxies, but it must have been spectacular!”

But these heavyweight stars were short-lived. Scientists think they quickly collapsed, leaving behind black holes –– objects with such extreme gravity that not even light can escape their clutches. Since the young universe was also smaller because it hadn’t been expanding very long, hordes of those black holes could have merged to form even bigger ones –– up to millions or even billions of times the Sun’s mass.

Supermassive black holes may have helped clear the hydrogen fog that permeated the early universe. Hot material swirling around black holes at the bright centers of active galaxies, called quasars, prior to falling in can generate extreme temperatures and send off huge, bright jets of intense radiation. The jets can extend for hundreds of thousands of light-years, ripping the electrons from any atom in their path.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is also exploring cosmic dawn, using its narrower but deeper view to study the early universe. By coupling Webb’s observations with Roman’s, scientists will generate a much more complete picture of this era.

So far, Webb is finding more quasars than anticipated given their expected rarity and Webb’s small field of view. Roman’s zoomed-out view will help astronomers understand what’s going on by seeing how common quasars truly are, likely finding tens of thousands compared to the handful Webb may find.

“With a stronger statistical sample, astronomers will be able to test a wide range of theories inspired by Webb observations,” Yung said.

Peering back into the universe’s first few hundred million years with Roman’s wide-eyed view will also help scientists determine whether a certain type of galaxy (such as more massive ones) played a larger role in clearing the fog.

“It could be that young galaxies kicked off the process, and then quasars finished the job,” Yung said. Seeing the size of the bubbles carved out of the fog will give scientists a major clue. “Galaxies would create huge clusters of bubbles around them, while quasars would create large, spherical ones. We need a big field of view like Roman’s to measure their extent, since in either case they’re likely up to millions of light-years wide –– often larger than Webb’s field of view.”

Roman will work hand-in-hand with Webb to offer clues about how galaxies formed from the primordial gas that once filled the universe, and how their central supermassive black holes influenced galaxy and star formation. The observations will help uncover the cosmic daybreakers that illuminated our universe and ultimately made life on Earth possible.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is managed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, with participation by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Caltech/IPAC in Southern California, the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, and a science team comprising scientists from various research institutions. The primary industrial partners are BAE Systems, Inc in Boulder, Colorado; L3Harris Technologies in Rochester, New York; and Teledyne Scientific & Imaging in Thousand Oaks, California.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 11.08.2024

-

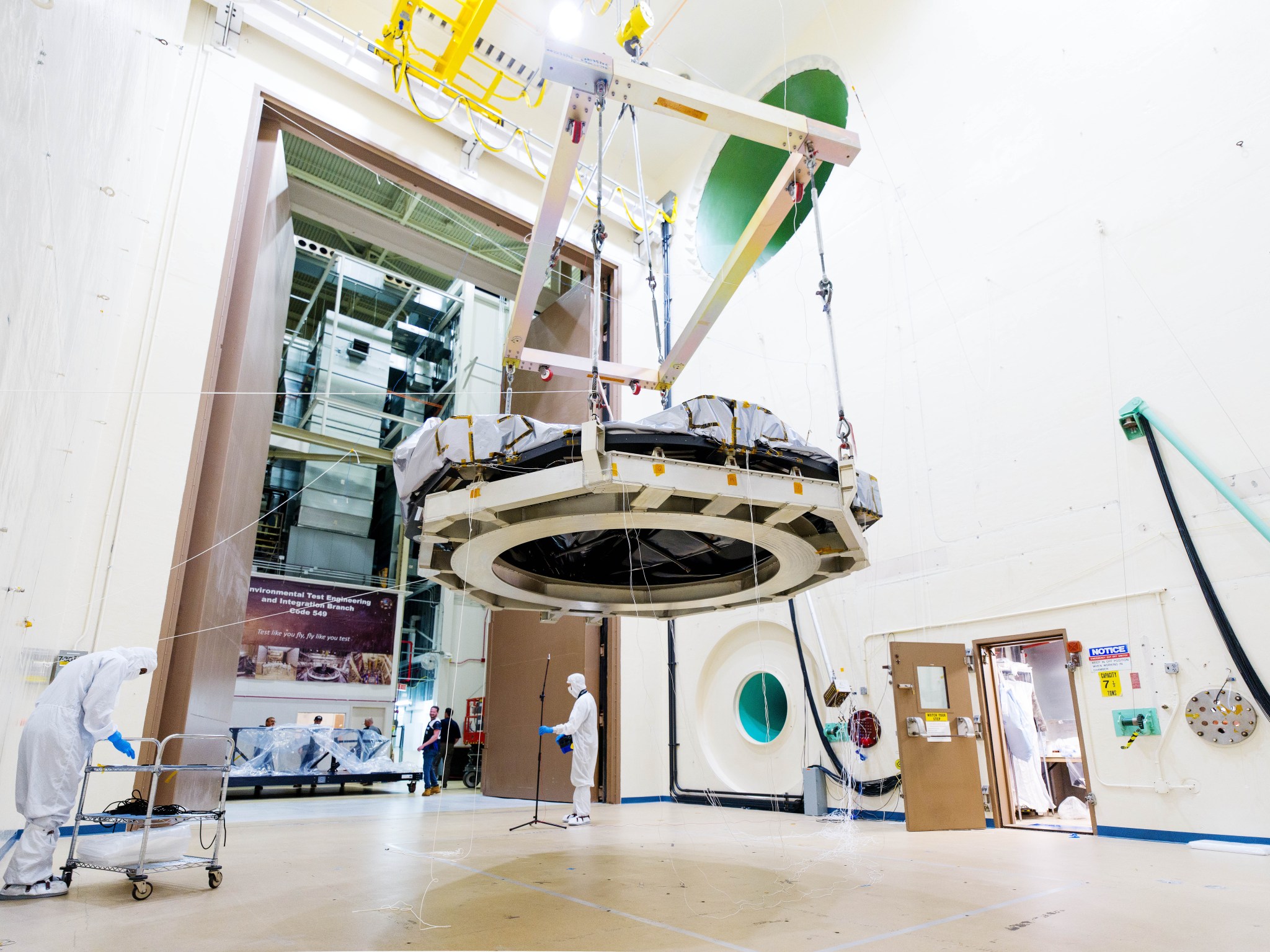

NASA Tests Deployment of Roman Space Telescope’s ‘Visor’

The “visor” for NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope recently completed several environmental tests simulating the conditions it will experience during launch and in space. Called the Deployable Aperture Cover, this large sunshade is designed to keep unwanted light out of the telescope. This milestone marks the halfway point for the cover’s final sprint of testing, bringing it one step closer to integration with Roman’s other subsystems this fall.

Designed and built at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, the Deployable Aperture Cover consists of two layers of reinforced thermal blankets, distinguishing it from previous hard aperture covers, like those on NASA’s Hubble. The sunshade will remain folded during launch and deploy after Roman is in space via three booms that spring upward when triggered electronically.

“With a soft deployable like the Deployable Aperture Cover, it’s very difficult to model and precisely predict what it’s going to do — you just have to test it,” said Matthew Neuman, a Deployable Aperture Cover mechanical engineer at Goddard. “Passing this testing now really proves that this system works.”

During its first major environmental test, the sunshade endured conditions simulating what it will experience in space. It was sealed inside NASA Goddard’s Space Environment Simulator — a massive chamber that can achieve extremely low pressure and a wide range of temperatures. Technicians placed the DAC near six heaters — a Sun simulator — and thermal simulators representing Roman’s Outer Barrel Assembly and Solar Array Sun Shield. Since these two components will eventually form a subsystem with the Deployable Aperture Cover, replicating their temperatures allows engineers to understand how heat will actually flow when Roman is in space.

When in space, the sunshade is expected to operate at minus 67 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 55 degrees Celsius. However, recent testing cooled the cover to minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 70 degrees Celsius — ensuring that it will work even in unexpectedly cold conditions. Once chilled, technicians triggered its deployment, carefully monitoring through cameras and sensors onboard. Over the span of about a minute, the sunshade successfully deployed, proving its resilience in extreme space conditions.

“This was probably the environmental test we were most nervous about,” said Brian Simpson, project design lead for the Deployable Aperture Cover at NASA Goddard. “If there’s any reason that the Deployable Aperture Cover would stall or not completely deploy, it would be because the material became frozen stiff or stuck to itself.”

If the sunshade were to stall or partially deploy, it would obscure Roman’s view, severely limiting the mission’s science capabilities.

After passing thermal vacuum testing, the sunshade underwent acoustic testing to simulate the launch’s intense noises, which can cause vibrations at higher frequencies than the shaking of the launch itself. During this test, the sunshade remained stowed, hanging inside one of Goddard’s acoustic chambers — a large room outfitted with two gigantic horns and hanging microphones to monitor sound levels.

With the sunshade plastered in sensors, the acoustic test ramped up in noise level, eventually subjecting the cover to one full minute at 138 decibels — louder than a jet plane’s takeoff at close range! Technicians attentively monitored the sunshade’s response to the powerful acoustics and gathered valuable data, concluding that the test succeeded.

“For the better part of a year, we’ve been building the flight assembly,” Simpson said. “We’re finally getting to the exciting part where we get to test it. We’re confident that we’ll get through with no problem, but after each test we can’t help but breathe a collective sigh of relief!”

Next, the Deployable Aperture Cover will undergo its two final phases of testing. These assessments will measure the sunshade’s natural frequency and response to the launch’s vibrations. Then, the Deployable Aperture Cover will integrate with the Outer Barrel Assemblyand Solar Array Sun Shield this fall.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 15.08.2024

.

Primary Instrument for Roman Space Telescope Arrives at NASA Goddard

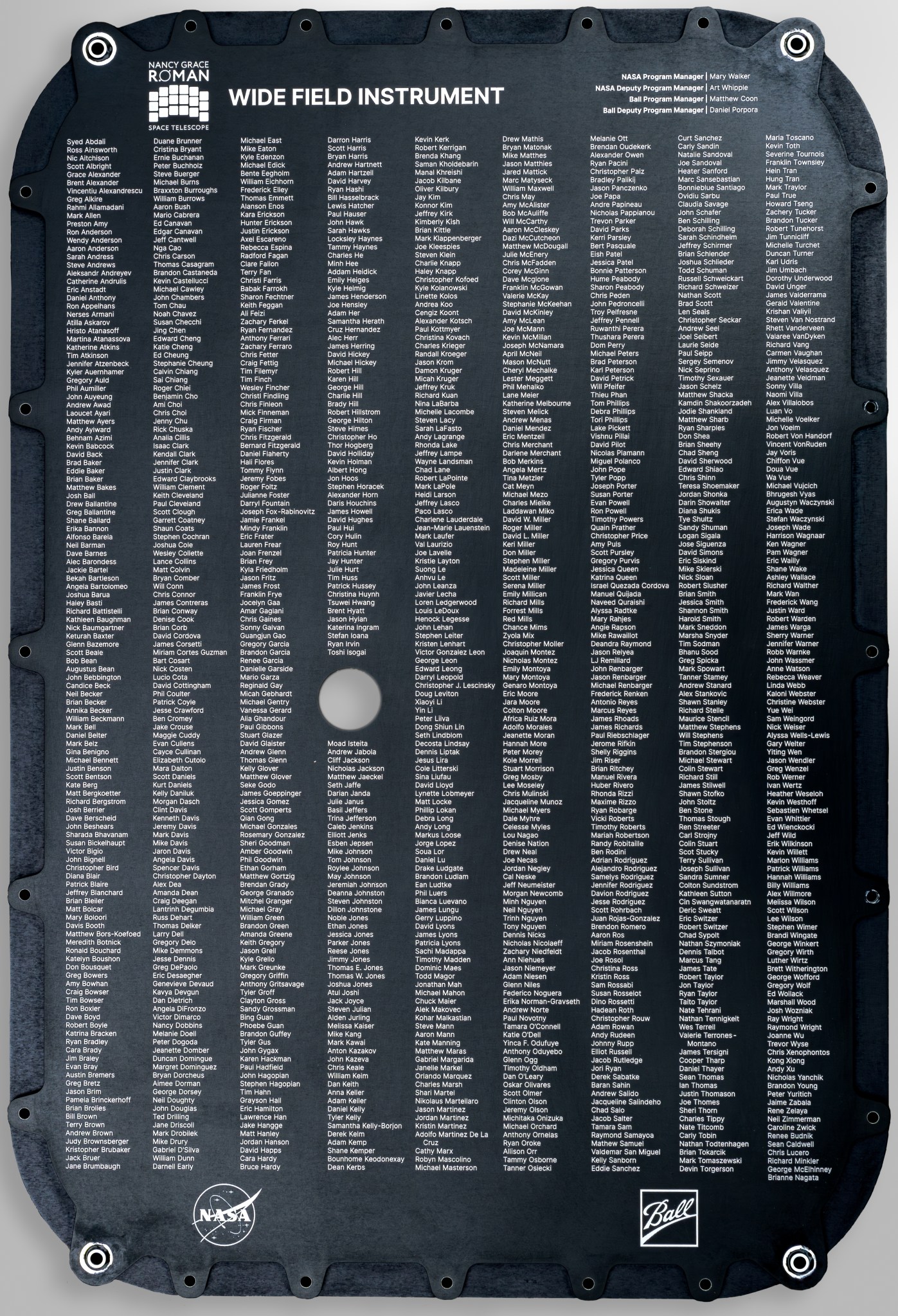

The primary instrument for NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is a sophisticated camera that will survey the cosmos from the outskirts of our solar system all the way out to the edge of the observable universe. Called the Wide Field Instrument, it was recently delivered to the agency’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The camera’s large field of view, sharp resolution, and sensitivity from visible to near-infrared wavelengths will give Roman a deep, panoramic view of the universe. Scanning much larger portions of the sky than astronomers can with NASA’s Hubble or James Webb space telescopes will open new avenues of cosmic exploration. Roman is designed to study dark energy (a mysterious cosmic pressure thought to accelerate the universe’s expansion), dark matter(invisible matter seen only via its gravitational influence), and exoplanets (worlds beyond our solar system).

“This instrument will turn signals from space into a new understanding of how our universe works,” said Julie McEnery, the Roman senior project scientist at Goddard. “To achieve its main goals, the mission will precisely measure hundreds of millions of galaxies. That’s quite a dataset for all kinds of researchers to pull from, so there will be a flood of results on a vast array of science.”

About 1,000 people contributed to the Wide Field Instrument’s development, from the initial design phase to assembling it from around a million individual components. The WFI’s design was a collaborative effort between Goddard and BAE Systems in Boulder, Colorado. Teledyne Imaging Sensors, Hawaii Aerospace Corporation, Applied Aerospace Structures Corporation, Northrop Grumman, Honeybee Robotics, CDA Intercorp, Alluxa, and JenOptik provided critical components. Those parts and many more, made by other vendors, were delivered to Goddard and BAE Systems, where they were assembled and tested prior to the instrument’s delivery to Goddard this month.

“I am so happy to be delivering this amazing instrument,” said Mary Walker, Roman’s Wide Field Instrument manager at Goddard. “All the years of hard work and the team’s dedication have brought us to this exciting moment.”

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Seeing the Bigger Picture

After Roman launches by May 2027, each of the Wide Field Instrument’s 300-million-pixel images will capture a patch of the sky bigger than the apparent size of a full moon. The instrument’s large field of view will enable sweeping celestial surveys, revealing billions of cosmic objects across vast stretches of time and space. Astronomers will conduct research that could take hundreds of years using other telescopes.

And by observing from space, Roman’s camera will be very sensitive to infrared light –– light with longer wavelengths than our eyes can see –– from far across the cosmos. This ancient cosmic light will help scientists address some of the biggest cosmic mysteries, one of which is how the universe evolved to its present state.

From the telescope, light’s path through the instrument begins by passing through one of several optical elements in a large wheel. These elements include filters, which allow specific wavelengths of light to pass through, and a grism and prism, which split light into all of its individual colors. These detailed patterns, called spectra, reveal information about the object that emitted the light.

Then, the light travels on toward the camera’s set of 18 detectors, which each contain 16 million pixels. The large number of detectors and pixels gives Roman its large field of view. The instrument is designed for accurate, stable images and exquisite precision in measuring the exact amount of light in every pixel of every image, giving Roman unprecedented power to study dark energy. The detectors will be held at about minus 300 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 184 degrees Celsius) to increase sensitivity to the infrared universe.

“When the light reaches the detectors, that marks the end of what may have been a 10-billion-year journey through space,” said Art Whipple, an aerospace engineer at Goddard who has contributed to the Wide Field Instrument’s design and construction for more than a decade.

Once Roman begins observing, its rapid data delivery will require new analysis techniques.

“If we had every astronomer on Earth working on Roman data, there still wouldn’t be nearly enough people to go through it all,” McEnery said. “We’re looking at modern techniques like machine learning and artificial intelligence to help sift through Roman’s observations and find where the most exciting things are.”

Now that the Wide Field Instrument is at Goddard, it will be tested to ensure everything is operating as expected. It will be integrated onto the instrument carrier and mated to the telescope this fall, bringing scientists one step closer to making groundbreaking discoveries for decades to come.