7.06.2024

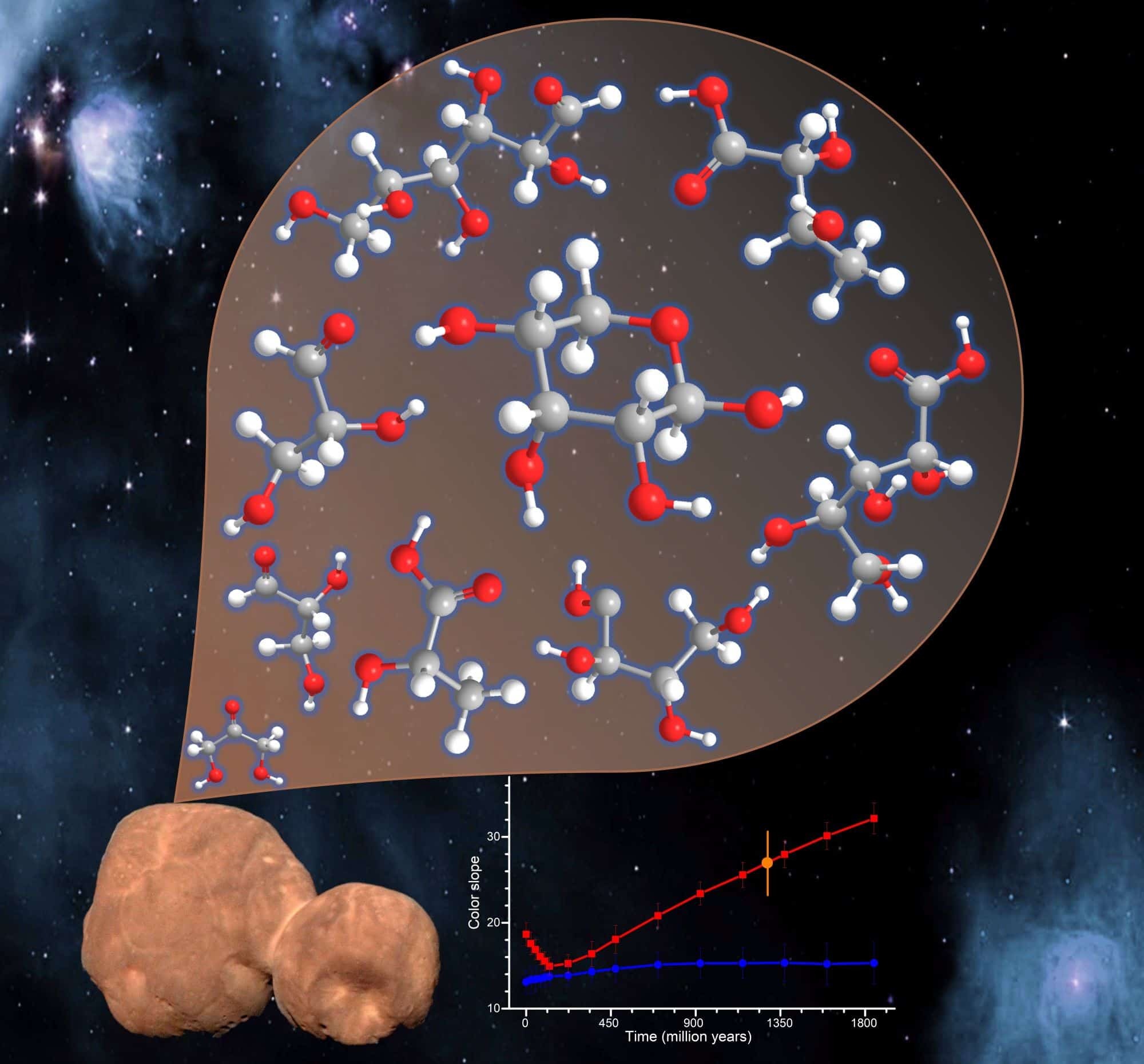

I spy something red: Some of the molecules found on the surface of Arrokoth, a reddish, lumpy world located in the Kuiper belt. By bombarding samples of frozen methane with simulated cosmic rays, the research team succeeded in recreating Arrokoth's unusual colour slope. (Courtesy: Chaojiang Zhang)

Now here’s a discovery that’s pretty sweet: the most distant Solar System object ever visited by a spacecraft appears to be dusted with sugar. Known as Arrokoth, this small, irregularly shaped world is reddish in colour, and scientists in the US and France say that its unusual hue may be due to the presence of glucose and other forms of sugar on its surface. The discovery has implications for the origins of life, as comets could have delivered organic molecules from “sugar worlds” like Arrokoth to the early Earth.

Arrokoth orbits the Sun as part of the Kuiper belt of objects beyond the planet Neptune. Because it formed when two objects collided and fused together, it looks a little like a flattened snowman, with a “head” and “body” 15 and 21 km in diameter. Nicknamed “Ultima Thule” by scientists working on the New Horizons mission, it gets its formal name from a word meaning “sky” or “cloud” in the Powhatan language spoken by Native Americans who lived on what is now the US East Coast before European settlers arrived there.

Apart from its knobbly shape, Arrokoth’s most distinctive feature is its colour. Unlike pink-tinged Pluto – the largest Kuiper belt object (KBO), and the subject of New Horizons’ first flyby in 2015 – Arrokoth is darker and reddish. The cause of this unusual colouring, which also occurs in a few other KBOs, is not fully understood. However, New Horizons detected abundant frozen methanol (CH3OH) on Arrokoth’s surface when it flew past in 2019, and scientists had previously found that irradiating methanol with ions significantly reddens its spectrum.

Enter the energetic electrons

In the new study, a team led by chemists Ralf I Kaiser of the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa and Cornelia Meinert of the Université Côte d’Azur, France, together with planetary scientist Leslie A Young of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, US, explored this possibility further by bombarding samples of methanol ice at 10 K and 40 K with energetic electrons. After exposing the samples to the equivalent of 1.8 billion years of galactic cosmic rays, they used a variety of spectroscopic methods to characterize the composition and colour of the organic molecules that formed.

The results showed that radiation bombardment can indeed replicate the colouration found on Arrokoth, with a dose of 57 eV per atomic mass unit creating an especially good colour match. Using gas chromatography and time-of-flight mass spectrometry, the team also identified sugar-related compounds such as glucose (C6H12O6) and ribose (C5H10O5) in residues of the radiation-exposed methanol ices. Some of these compounds, the researchers note, are incorporated into the molecules that make up RNA and lipids, providing what they call “a plausible source of this key class of prebiotic molecules for the evolution of life on early Earth”.

As for how these chemicals got from Arrokoth or other Kuiper belt objects to Earth, in a PNAS paper describing the study, the researchers point out that the Kuiper belt is thought to be a major source of short-period comets. “These sugars and their derivatives could have been delivered by KBOs like Arrokoth in the form of short-period comets impacting the early Earth, thus providing a source of a variety of sugars and the feedstock for important biomolecules,” they write. Future experiments on more complex ice mixtures containing ammonia, water and carbon dioxide as well as methane could, they suggest, yield further insights on the optical spectra and composition of KBOs not visited by spacecraft.

Quelle: physicsworld