16.04.2024

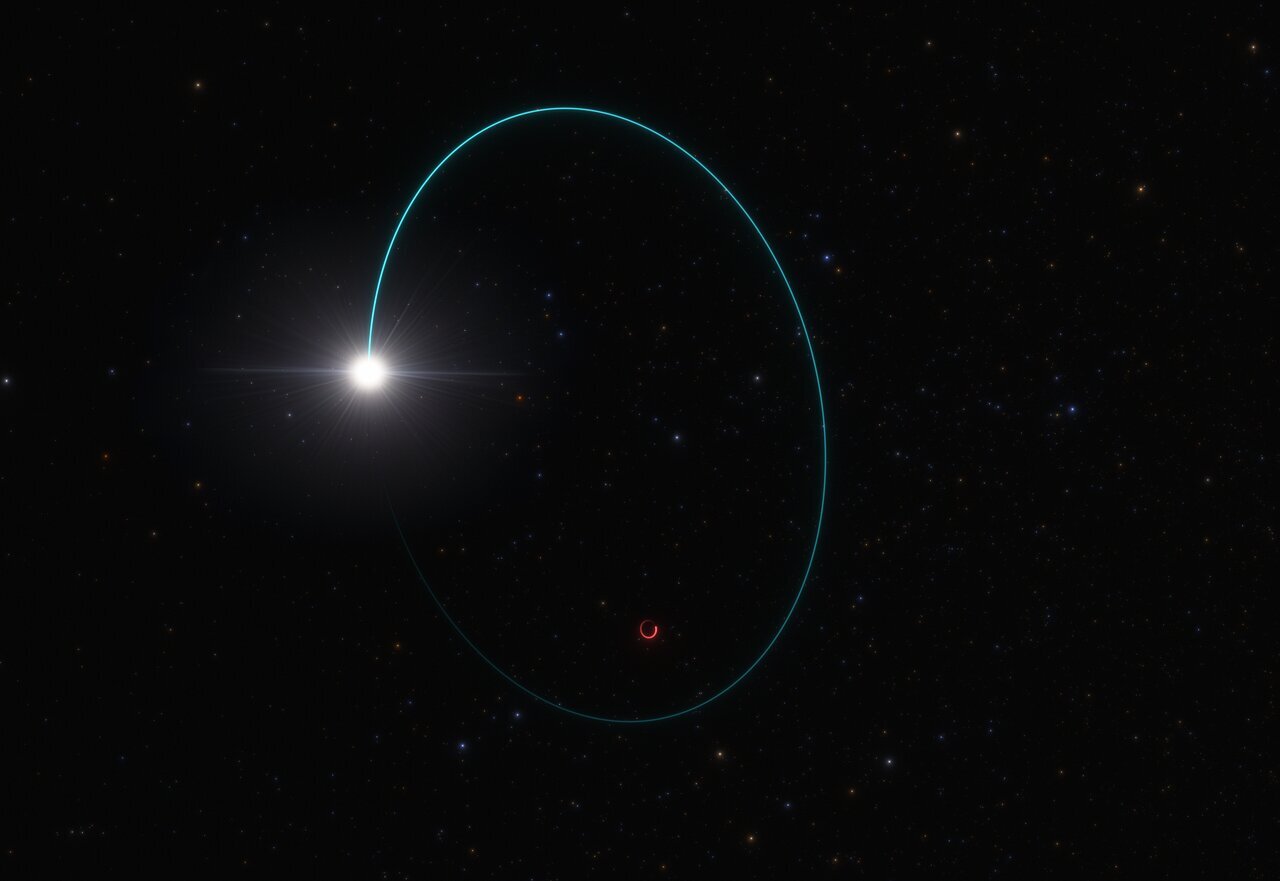

Artist’s impression of the system with the most massive stellar black hole in our galaxy

Astronomers have identified the most massive stellar black hole yet discovered in the Milky Way galaxy. This black hole was spotted in data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission because it imposes an odd ‘wobbling’ motion on the companion star orbiting it. Data from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) and other ground-based observatories were used to verify the mass of the black hole, putting it at an impressive 33 times that of the Sun.

Stellar black holes are formed from the collapse of massive stars and the ones previously identified in the Milky Way are on average about 10 times as massive as the Sun. Even the next most massive stellar black hole known in our galaxy, Cygnus X-1, only reaches 21 solar masses, making this new 33-solar-mass observation exceptional [1].

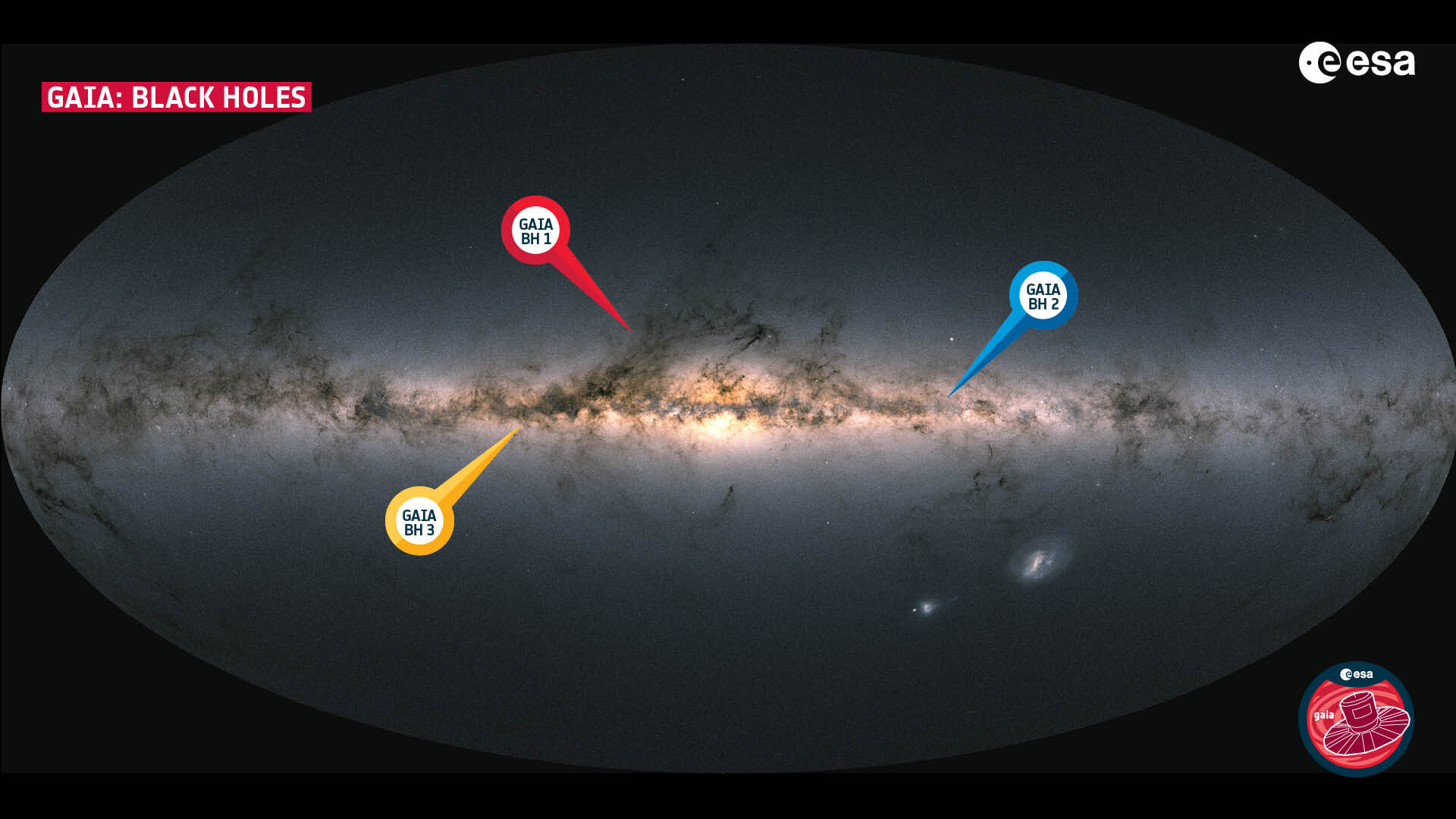

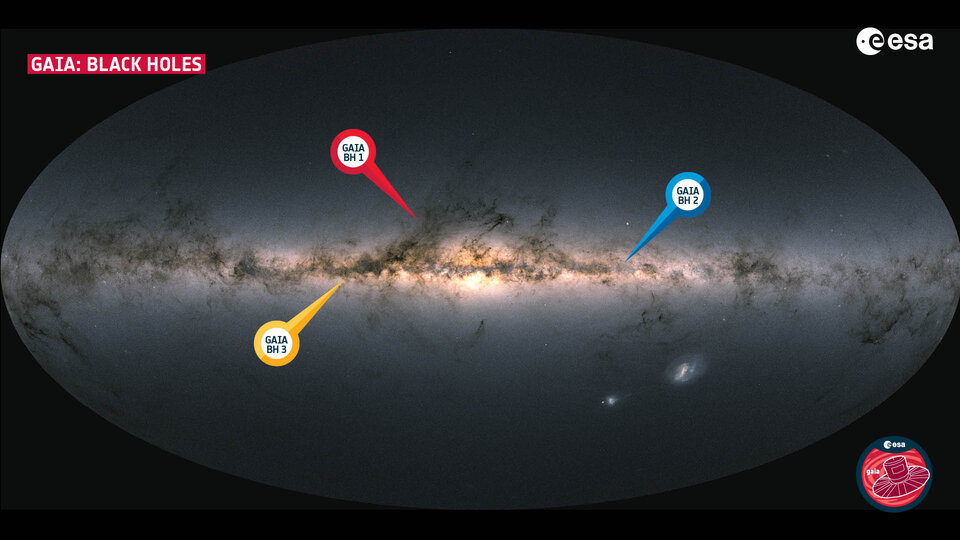

Remarkably, this black hole is also extremely close to us — at a mere 2000 light-years away in the constellation Aquila, it is the second-closest known black hole to Earth. Dubbed Gaia BH3 or BH3 for short, it was found while the team were reviewing Gaia observations in preparation for an upcoming data release. “No one was expecting to find a high-mass black hole lurking nearby, undetected so far,” says Gaia collaboration member Pasquale Panuzzo, an astronomer from the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) at the Observatoire de Paris - PSL, France. "This is the kind of discovery you make once in your research life."

To confirm their discovery, the Gaia collaboration used data from ground-based observatories, including from the Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph (UVES) instrument on ESO’s VLT, located in Chile’s Atacama Desert [2]. These observations revealed key properties of the companion star, which, together with Gaia data, allowed astronomers to precisely measure the mass of BH3.

Astronomers have found similarly massive black holes outside our galaxy (using a different detection method), and have theorised that they may form from the collapse of stars with very few elements heavier than hydrogen and helium in their chemical composition. These so-called metal-poor stars are thought to lose less mass over their lifetimes and hence have more material left over to produce high-mass black holes after their death. But evidence directly linking metal-poor stars to high-mass black holes has been lacking until now.

Stars in pairs tend to have similar compositions, meaning that BH3’s companion holds important clues about the star that collapsed to form this exceptional black hole. UVES data showed that the companion was a very metal-poor star, indicating that the star that collapsed to form BH3 was also metal-poor — just as predicted.

The research study, led by Panuzzo, is published today in Astronomy & Astrophysics. “We took the exceptional step of publishing this paper based on preliminary data ahead of the forthcoming Gaia release because of the unique nature of the discovery,” says co-author Elisabetta Caffau, also a Gaia collaboration member and CNRS scientist from the Observatoire de Paris - PSL. Making the data available early will let other astronomers start studying this black hole right now, without waiting for the full data release, planned for late 2025 at the earliest.

Further observations of this system could reveal more about its history and about the black hole itself. The GRAVITYinstrument on ESO’s VLT Interferometer, for example, could help astronomers find out whether this black hole is pulling in matter from its surroundings and better understand this exciting object.

Notes

[1] This is not the most massive black hole in our galaxy — that title belongs to Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the Milky Way’s centre, which has about four million times the mass of the Sun. But Gaia BH3 is the most massive black hole known in the Milky Way that formed from the collapse of a star.

[2] Aside from UVES on ESO’s VLT, the study relied on data from: the HERMES spectrograph at the Mercator Telescope operated at La Palma (Spain) by Leuven University, Belgium, in collaboration with the Observatory of the University of Geneva, Switzerland; and the SOPHIE high-precision spectrograph at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence – OSU Institut Pythéas.

Quelle: ESO

+++

Sleeping giant surprises Gaia scientists

Wading through the wealth of data from ESA’s Gaia mission, scientists have uncovered a ‘sleeping giant’. A large black hole, with a mass of nearly 33 times the mass of the Sun, was hiding in the constellation Aquila, less than 2000 light-years from Earth. This is the first time a black hole of stellar origin this big has been spotted within the Milky Way. So far, black holes of this type have only been observed in very distant galaxies. The discovery challenges our understanding of how massive stars develop and evolve.

Matter in a black hole is so densely packed that nothing can escape its immense gravitational pull, not even light. The great majority of stellar-mass black holes that we know of are gobbling up matter from a nearby star companion. The captured material falls onto the collapsed object at high speed, becoming extremely hot and releasing X-rays. These systems belong to a family of celestial objects named X-ray binaries.

When a black hole does not have a companion close enough to steal matter from, it does not generate any light and is extremely difficult to spot. These black holes are called ‘dormant’.

To prepare for the release of the next Gaia catalogue, Data Release 4 (DR4), scientists are checking the motions of billions of stars and carrying out complex tests to see if anything is out of the ordinary. The motions of stars can be affected by companions: light ones, like exoplanets; heavier ones, like stars; or very heavy ones, like black holes. Dedicated teams are in place in the Gaia Collaboration to investigate any ‘odd’ cases.

One such team was deeply engaged in this work, when their attention fell on an old giant star in the constellation Aquila, at a distance of 1926 light-years from Earth. By analysing in detail the wobble in the star’s path, they found a big surprise. The star was locked in an orbital motion with a dormant black hole of exceptionally high mass, about 33 times that of the Sun.

This is the third dormant black hole found with Gaia and was aptly named ‘Gaia BH3’. Its discovery is very exciting because of the mass of the object. “This is the kind of discovery you make once in your research life,” exclaims Pasquale Panuzzo of CNRS, Observatoire de Paris, in France, who is the lead author of this finding. “So far, black holes this big have only ever been detected in distant galaxies by the LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA collaboration, thanks to observations of gravitational waves.”

The average mass of known black holes of stellar origin in our galaxy is around 10 times the mass of our Sun. Until now, the weight record was held by a black hole in an X-ray binary in the Cygnus constellation (Cyg X-1), whose mass is estimated to be around 20 times that of the Sun.

“It’s impressive to see the transformational impact Gaia is having on astronomy and astrophysics,” notes Prof. Carole Mundell, ESA Director of Science. “Its discoveries are reaching far beyond the original purpose of the mission, which is to create an extraordinarily precise multi-dimensional map of more than a billion stars throughout our Milky Way."

Unmatched accuracy

The exquisite quality of the Gaia data enabled scientists to pin down the mass of the black hole with unparalleled accuracy and provide the most direct evidence that black holes in this mass range exist.

Astronomers face the pressing question of explaining the origin of black holes as large as Gaia BH3. Our current understanding of how massive stars evolve and die does not immediately explain how these types of black holes came to be.

Most theories predict that, as they age, massive stars shed a sizable part of their material through powerful winds; ultimately, they are partly blown into space when they explode as supernovas. What remains of their core further contracts to become either a neutron star or a black hole, depending on its mass. Cores large enough to end up as black holes of 30 times the mass of our Sun are very difficult to explain.

Yet, a clue to this puzzle may lie very close to Gaia BH3.

An intriguing companion

The star orbiting Gaia BH3 at about 16 times the Sun–Earth distance is rather uncommon: an ancient giant star, that formed in the first two billion years after the Big Bang, at the time our galaxy started to assemble. It belongs to the family of the Galactic stellar halo and is moving in the opposite direction to the stars of the Galactic disc. Its trajectory indicates that this star was probably part of a small galaxy, or a globular cluster, engulfed by our own galaxy more than eight billion years ago.

The companion star has very few elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, indicating that the massive star that became Gaia BH3 could also have been very poor in heavy elements. This is remarkable. It supports, for the first time, the theory that the high-mass black holes observed by gravitational wave experiments were produced by the collapse of primeval massive stars poor in heavy elements. These early stars might have evolved differently from the massive stars we currently see in our galaxy.

The composition of the companion star can also shed light on the formation mechanism of this astonishing binary system. "What strikes me is that the chemical composition of the companion is similar to what we find in old metal-poor stars in the galaxy,” explains Elisabetta Caffau of CNRS, Observatoire de Paris, also a member of the Gaia collaboration.

“There is no evidence that this star was contaminated by the material flung out by the supernova explosion of the massive star that became BH3.” This could suggest that the black hole acquired its companion only after its birth, capturing it from another system.

Tasty appetiser

The discovery of the Gaia BH3 is only the beginning and much remains to be investigated about its baffling nature. Now that the scientists’ curiosity has been piqued, this black hole and its companion will undoubtedly be the subject of many in-depth studies to come.

The Gaia collaboration stumbled upon this ‘sleeping giant’ while checking the preliminary data in preparation for the fourth release of the Gaia catalogue. Because the finding is so exceptional they decided to announce it ahead of the official release.

The next release of Gaia data promises to be a goldmine for the study of binary systems and the discovery of more dormant black holes in our galaxy. “We have been working extremely hard to improve the way we process specific datasets compared to the previous data release (DR3), so we expect to uncover many more black holes in DR4,” concludes Berry Holl of the University of Geneva, in Switzerland, member of the Gaia collaboration.

Access the video

Notes for editors

"Discovery of a dormant 33 solar-mass black hole in pre-release Gaia astrometry" by Gaia Collaboration, P. Panuzzo, et al. is published today the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics (A&A).

Gaia is a European mission, built and operated by ESA. It was approved in 2000 as a European Space Agency Cornerstone Mission within ESA’s Horizon 2000 Plus science programme, supported by all ESA Member States. Member States also have a key role in the science portion of the mission as part of the Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC) responsible to turn the raw data into scientific products for Gaia Data Releases, in collaboration with ESA. DPAC brings together more than 450 specialists from throughout the scientific community in Europe. Gaia was designed and built by Astrium (now Airbus Defence and Space), with a core team composed of Astrium France, Germany and UK. The industrial team included 50 companies from 15 European states, along with firms from the US. The spacecraft was launched by Arianespace on 19 December 2013.

Quelle: ESA