16.02.2024

Small scopes on IM-1 mission would be first optical and radio observatories on the lunar surface

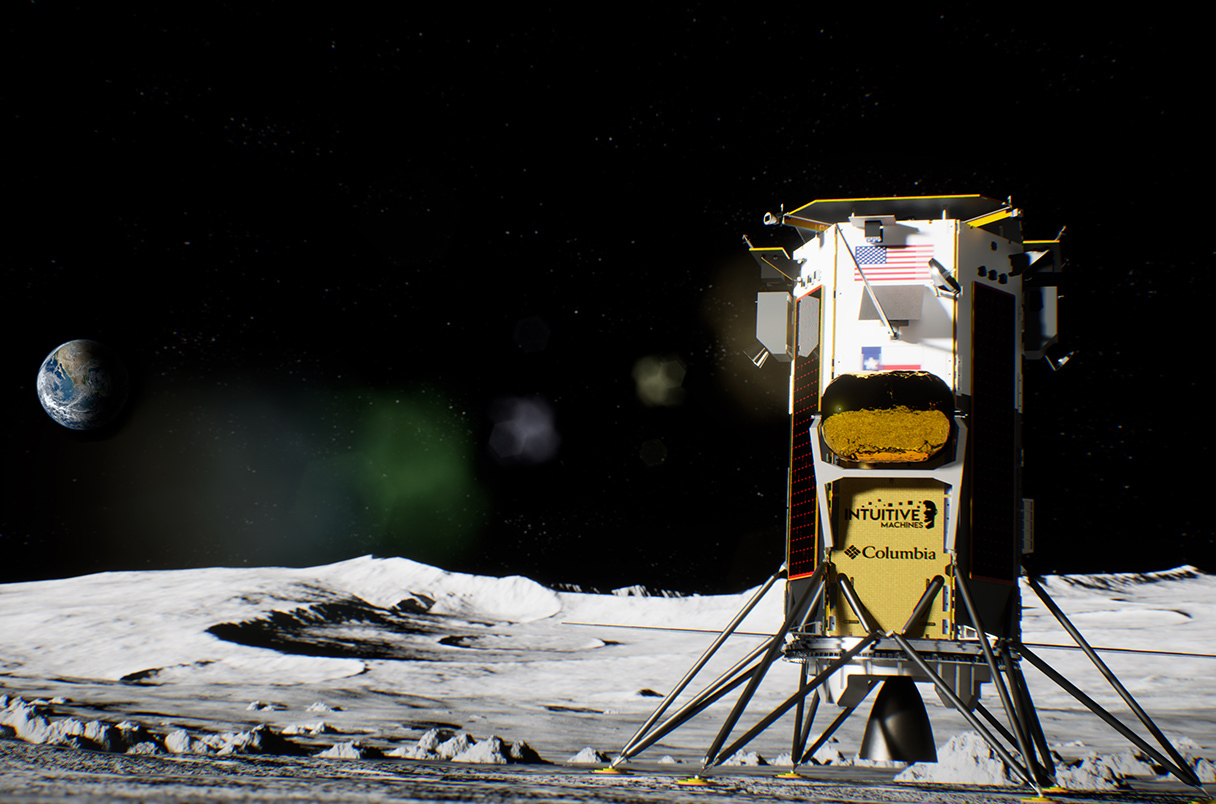

In 1 week, Intuitive Machines plans to land its IM-1 spacecraft in the Malapert A crater near the Moon’s south pole.INTUITIVE MACHINES

A commercial spacecraft set off today carrying two small observatories that could showcase the potential of the Moon as an astronomical platform. One, an optical telescope, aims to demonstrate the viability of lunar astronomy and encourage exploration. The other, a radio telescope, will measure Earth’s reactions to solar flare-ups and look for a predicted “electron sheath” above the Moon’s surface. Both would be the first instruments of their kind on the Moon.

“It’s a new frontier for astronomy,” says Steve Durst, director of the International Lunar Observatory Association (ILOA), an education and science nonprofit building the ILO-X optical telescope. “It’s very humbling.”

Astronomers have long eyed the Moon as a good spot to do their work. Its far side, protected from Earth’s hectic radio noise, is perfect for picking up faint signals from the distant universe. To see infrared signals blocked by Earth’s atmosphere, astronomers usually go to space, but orbiting infrared telescopes, such as NASA’s JWST, require sunshields and coolants to chill detectors to temperatures close to absolute zero. Put the telescope into one of the deep craters at the lunar poles that never receive any sunlight and its sensors will benefit from the crater’s permanent chill. Gravitational wave detectors could grow to enormous size and become extremely sensitive on the seismically quiet lunar surface.

Astronomers hope governments’ renewed enthusiasm for lunar exploration will provide them with opportunities. But they worry a Moon rush could also lead to development, such as mining, which could threaten the pristine conditions that attract them. So they are agitating to protect scientifically valuable lunar sites.

Only two telescopes have operated from the Moon so far. Both have worked in the ultraviolet—another wavelength blocked by Earth’s atmosphere. One was operated by Apollo 16 astronauts during their 1972 mission. The second landed in 2013 as part of China’s Chang’e-3 mission and is still operating more than a decade later.

Today’s mission, dubbed IM-1, was built by the company Intuitive Machines on a contract with NASA as part of its Commercial Lunar Payload Services program and launched on a SpaceX Falcon 9. If it lands successfully next week in the Malapert A crater, 300 kilometers from the lunar south pole, it will be the first U.S. soft landing on the Moon in more than 50 years. The lander, roughly the height and weight of a small car stood on end, carries a dozen NASA and commercial payloads, including a cube containing 125 little sculptures from the artist Jeff Koons, along with the two telescopes

The optical instrument, ILO-X, consists of narrow- and wide-field cameras, each 3 centimeters in aperture, attached to the IM-1 lander. It aims to image the Milky Way and its center, the Large Magellanic Cloud, and other bright objects including the Carina nebula. There’s a limit to what can be achieved with such small cameras on fixed mounts, and ILO-X is mainly intended as a proof of principle for larger planned telescopes. But Durst says ILOA has invited 10 prominent astronomers and other backers to suggest targets for observations.

The other telescope, ROLSES (Radiowave Observations at the Lunar Surface of the photoElectron Sheath), will deploy four 2.5-meter-long antennas from the IM-1 lander to study the magnetic fields of the Sun and Earth and how they interact. Solar flares can energize particles in Earth’s aurora, which in turn produce radio signals. Studying the signals from a lunar vantage point could help radio astronomers eventually detect such signals from distant worlds—one of the only ways to peer inside an exoplanet with a magnetic field. If astronomers can scale up and build a planned array 10 kilometers across on the lunar far side, it “could see dozens of habitable planets,” says Jack Burns, an astronomer at the University of Colorado Boulder and co–principal investigator for ROLSES, which was funded by NASA and built by the Goddard Space Flight Center.

ROLSES also aims to study the Moon’s electron sheath, a haze of charged particles that is thought to shroud the sunlit side of the Moon, created by solar wind and cosmic rays hitting the surface. “We’ll take a first crack at detecting it and measuring its density,” Burns says. Not only could the sheath interfere with future radio observations, but it could also threaten astronauts by causing large static charges to build up on spacesuits. They could discharge if astronauts moved suddenly from day to night—something Apollo astronauts never did.

The team will also produce a low-resolution map of the sky at very low radio frequencies, below 30 megahertz. Such radiation is inaccessible on Earth because it is blocked by the atmosphere. “It will be a start,” Burns says. His team is planning a larger observatory, called LuSEE-Night, on a dedicated lander that would be sensitive to these frequencies and could look deep into the cosmos and begin to probe a time before any stars were shining. That period, known as the universe’s dark ages, “is a playground for new physics,” Burns says. “We’ll be able to test fundamental models of physics and cosmology,” he says—without any pesky stars confusing the picture.

Quelle: AAAS