28.11.2023

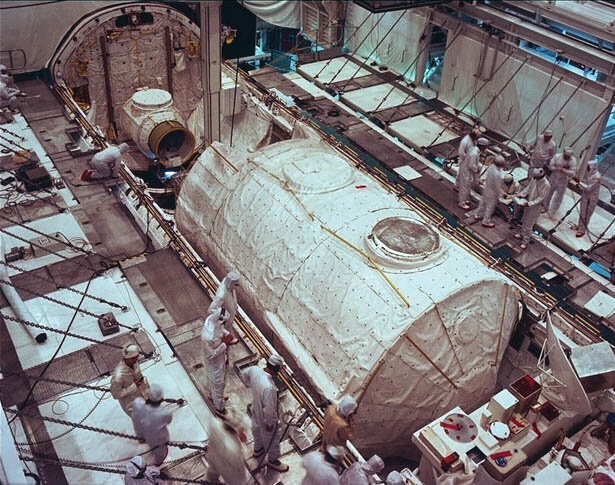

ESA’s first human spaceflight mission lifted off 40 years ago today. Accompanied by the first ESA astronaut, Ulf Merbold, the Spacelab module took flight inside the Space Shuttle’s cargo bay, turning NASA’s ‘space truck’ into a mini-space station for scientific research. Europe continues to be highly active in the crewed module business to this day.

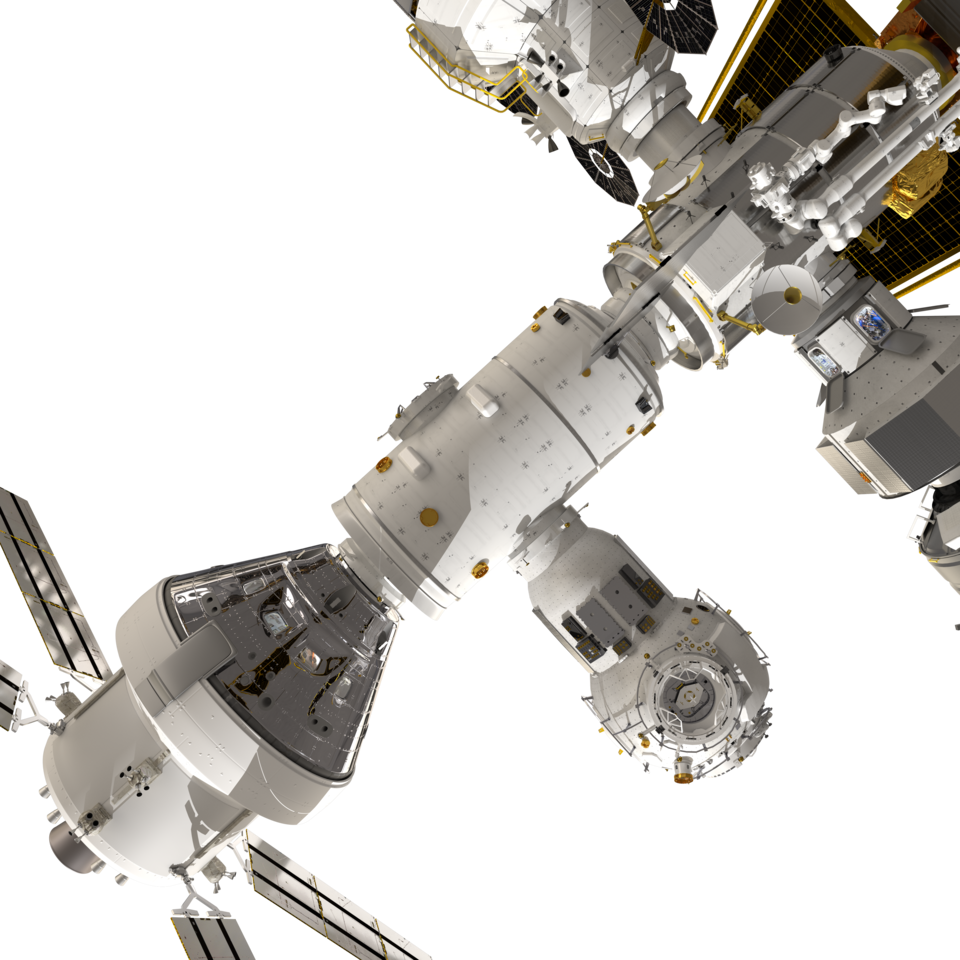

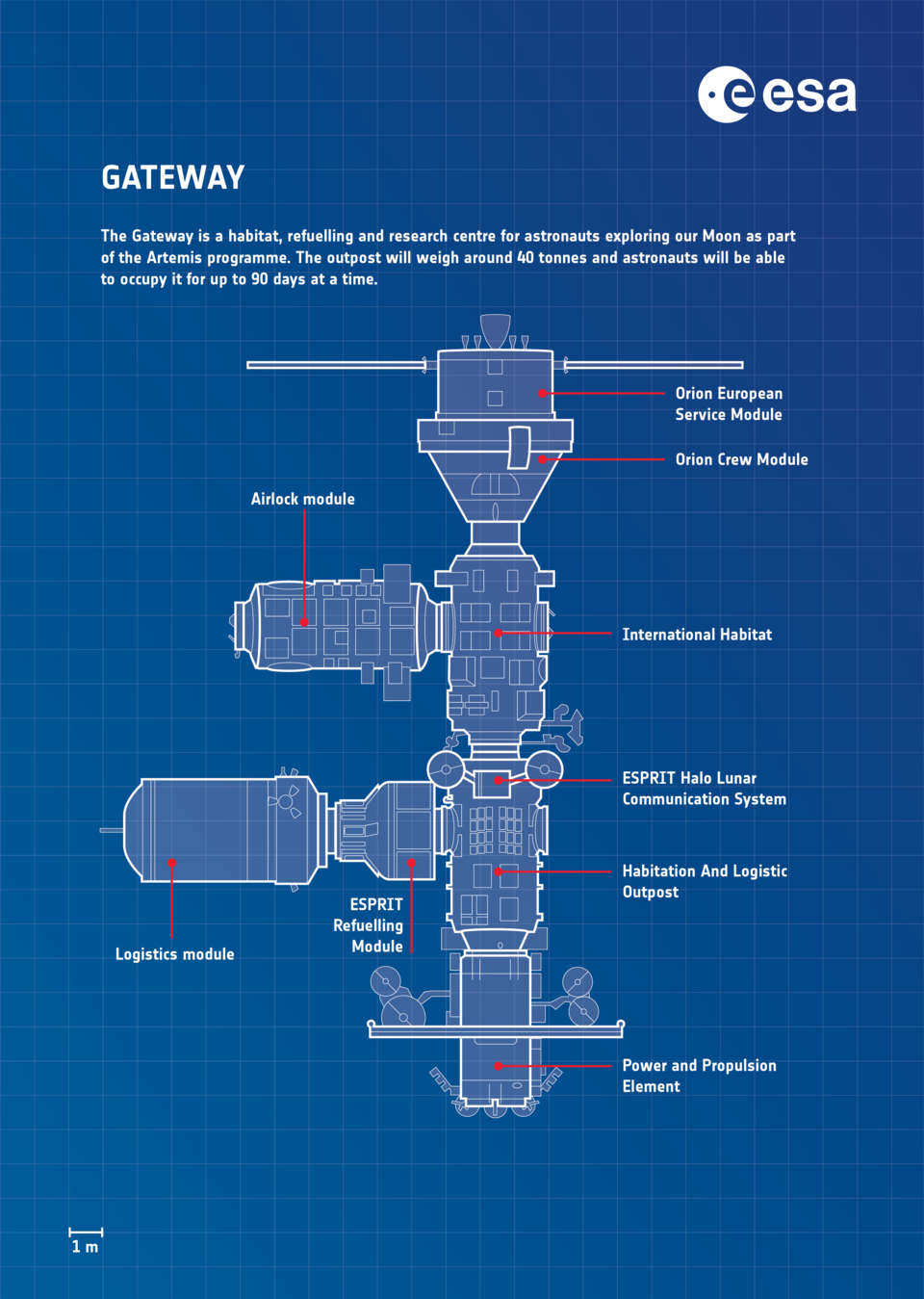

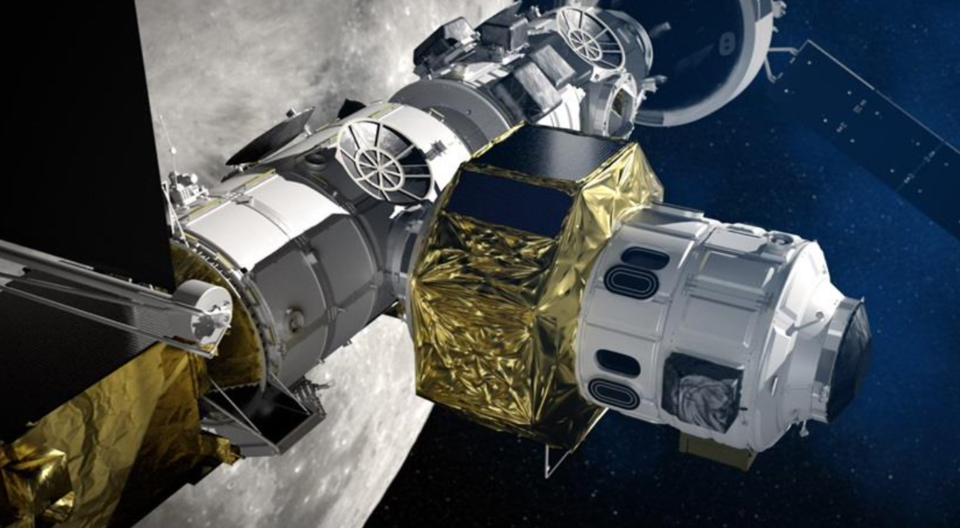

After Spacelab came ESA’s Columbus laboratory among many other modules of the International Space Station – Node 2, Node 3 and the Earth-watching Cupola – the ATV and Cygnus cargo spacecraft, the European Service Module of the Orion lunar orbiter, modules for the private Axiom space station and now crucial elements of the Gateway station due to orbit the Moon.

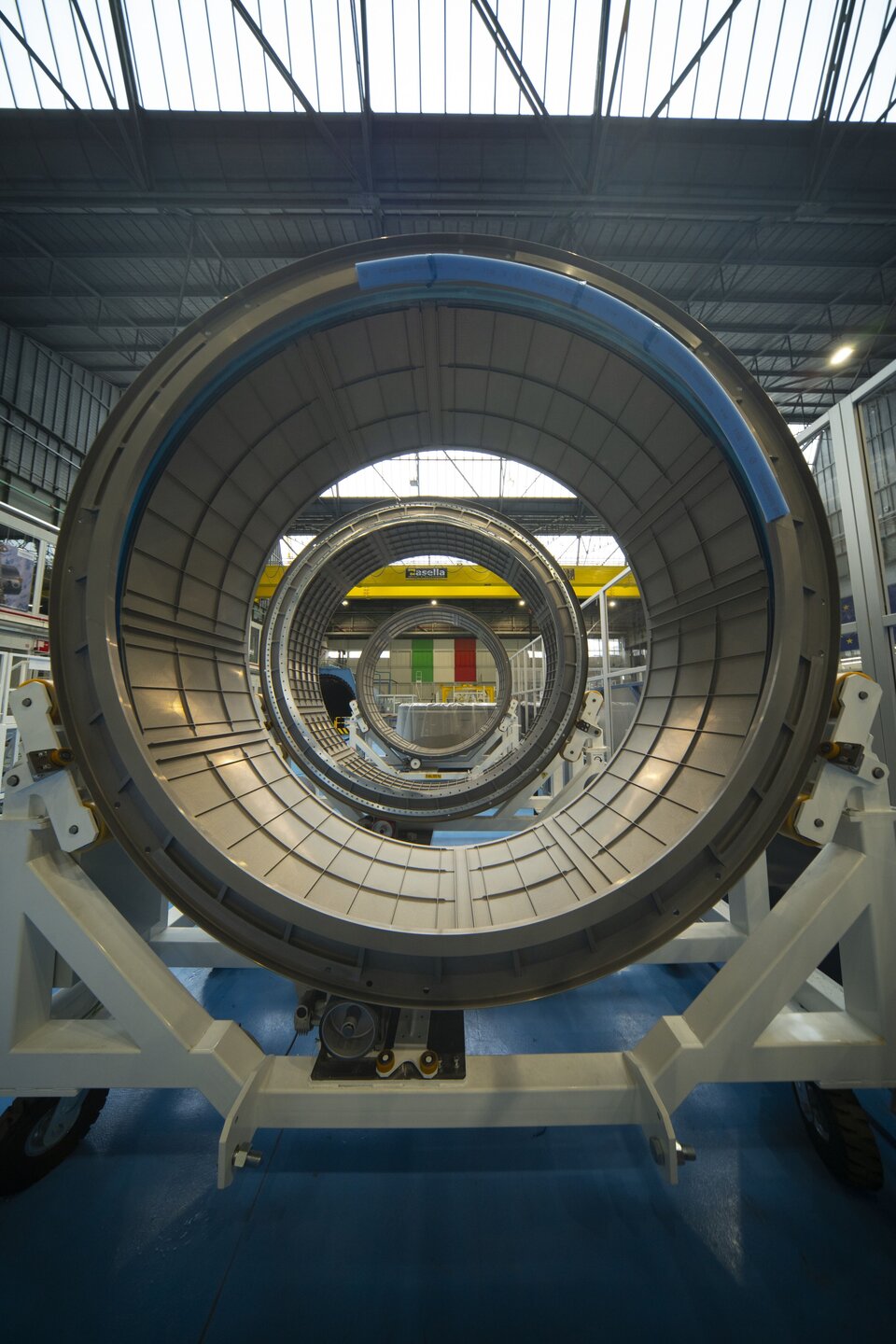

The industrial legacy of Spacelab is clear. The companies involved have changed names several times since the 1970s, but pressure shells are still being machined from space-grade aluminium-copper alloy 2219 in Turin, Italy – in premises run today by Thales Alenia Space.

In some cases these shells go on to be integrated on the spot in Turin, as in the case of ESA’s Gateway modules. For other product lines, such as the Orion ESMs, integration halls at Bremen in Germany fit them with equipment needed to make them spaceworthy, as was done for Spacelab more than four decades ago. Today these form part of an Airbus Defence and Space facility.

Keeping vacuum at bay

Pressure shells are a fundamental element of module design, serving to keep external vacuum at bay. They are made of metal sheets a few millimetres thick, shaped into cylinders, bounded by conical end pieces. Spacelab measured 6.7 m in length with a diameter of 4.1 m, the latter set by the dimensions of the Shuttle cargo bay in which it sat. Columbus and the other European-made ISS modules have just slightly larger diameters for the same reason.

By comparison, ESA’s International Habitat module for the Gateway, I-Hab is about 8 m long but just 3 m in diameter – the same width as the Turin-made pressure shell for the ISS-resupplying Cygnus. ESA’s other Gateway module, the ESPRIT Refuelling Module is 6.4 m in length and 4.6 m in diameter, though a large part of its volume is taken up with fuel tanks, plus a window-fitted pressure tunnel that astronauts can pass through, that has the same length and diameter as I-Hab.

“Gateway elements might be smaller than previous European modules but should also be stronger,” explains ESA materials and processes engineer Joao Gandra. “The big difference is that – as with Europe’s latest Axiom and Cygnus pressure shells – they are now welded using ‘friction stir welding’, which softens rather than melts metals, applying friction to join them together. While traditional welding can impart stresses into joints, this technique results in stronger welds with improved performance.”

“Today all our modules are made in this way,” adds Walter Cugno, VP of Exploration and Science at Thales Alenia Space, who worked on Spacelab as a product assurance engineer. “Our capability to supply pressurised elements – built up initially through ESA projects, along with bilateral agreements between Italian space agency ASI and NASA to produce ISS modules – is a key asset for all human exploration initiatives, in low-Earth orbit, the Moon and eventually on Mars.”

The I-Hab will serve as living quarters aboard the multi-module Gateway for crews of four for up to 30 days at a time.

Mark Wagner, leading ESA’s Lunar Gateway Baseline, Verification and Assembly, Integration and Testing Team, is helping ensure the module is ready for duty, and a launch currently scheduled for 2028.

Working with Gateway partners

Mark explains: “This is only one module making up a multi-module station, so we need to verify that I-Hab is compatible with all the interfaces agreed with our partner agencies such as NASA, the Canadian Space Agency and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. Adding to that, our development schedules are not in parallel: NASA’s HALO module – whose pressure shell is also being sourced from Turin – and the Power and Propulsion Element are due to fly together first. We need to be sure that all intermodule interfaces and functions are compatible with the rest of the international Gateway programme.

“As one example, I-Hab’s Environmental Control and Life Support System, being supplied to us by JAXA, needs to work together with its equivalent in HALO. The I-Hab module thermal control system is interconnected by heat exchangers with the other modules and visiting vehicles serving the entire Gateway outpost to dump heat loads via external pumped radiators to deep space. These and other combined systems need to work together flawlessly.”

Close quarters

I-Hab’s relatively small size was set by launch mass constraints. The module designers had to rise to the challenge of fitting all necessary systems into just 10 cubic metres of habitable volume, including scientific equipment, cooking facilities including a pull-out galley table, stores, life support and even a quartet of private booths for sleeping.

“Previous ISS modules – like Spacelab before them – were designed with an up and down orientation just because astronauts find that easier to work with. With I-Hab we don’t really have that luxury, because we need to make use of all available space as efficiently as we can, while at the same time fulfilling all human factor and crew-performance-related requirements.”

There will be no toilet however, for the time being; the crew will have to pop back to Orion for that. And early expeditions will have to bring their own consumables with them, one of the reasons that missions will be limited to 30 days at a time, together with high levels of deep space radiation. So for the majority of each year the Gateway will be uncrewed and will need to be overseen accordingly.

Astronaut testing

To check that I-Hab is a suitable a place to live and work in, the module development team have turned to veteran ESA astronauts including Samantha Cristoferreti, Alexander Gerst and Luca Parmitano, for early ‘human in the loop’ design assessments. There will be also human testing campaigns based on a representative mock-up of I-Hab installed at Thales Alenia in Turin as well as making use of VR – and in future combining the two in the form of augmented reality applications.

“We really aim to draw on the experience they have from working in orbit aboard ISS,” adds Mark. “They are helping our development team to check on all kinds of variables, like the quality of the lighting, the legibility of labels, the emergency egress layout, even the crew compartments – how suitable they are for privacy and sleep.”

I-Hab will aim for the same shirtsleeves working environment engineered for Spacelab and the ISS modules, with a 22°C temperature and 50% humidity, although the atmospheric pressure will be 0.7 atmospheres compared to the sea level pressure that prevails on the Station, helping drive down mass.

Mark adds: “Despite being smaller, I-Hab will be more inclusive in the sense we are designing for 99% astronaut accommodation, meaning almost all the very smallest female astronauts to the biggest male astronauts will be able to operate equipment easily and comfortably – such as opening hatches or rapidly disconnecting fluid lines – compared to an equivalent 95 percentile figure for the ISS.”

I-Hab’s development has passed through its Preliminary Design Review (PDR) and is currently in its detailed design phase. For the second ESA-provided Gateway module, ERM – the ESPRIT Refueling Module, the contractual agreement is currently being finalised, while its PDR is due soon.

This latest example of European crewed module development has a design lifetime of 15 years although judging by the example of the ISS, it is likely to go on operating for much longer still.

Based on the current architecture of the lunar Gateway outpost, more than half of this inspiring space station will be European in origin.

And Europe’s basic Spacelab-inspired module template looks likely to venture still further into space, with a contract recently signed between ASI and Thales Alenia Space to design modules for the lunar surface, to function as part of a future Moon base.

Quelle: ESA