12.06.2023

The stars and constellations that make up the Spring Triangle reach their highest point as the season comes to an end, making for a perfect time to observe the nearby "Realm of the Galaxies."

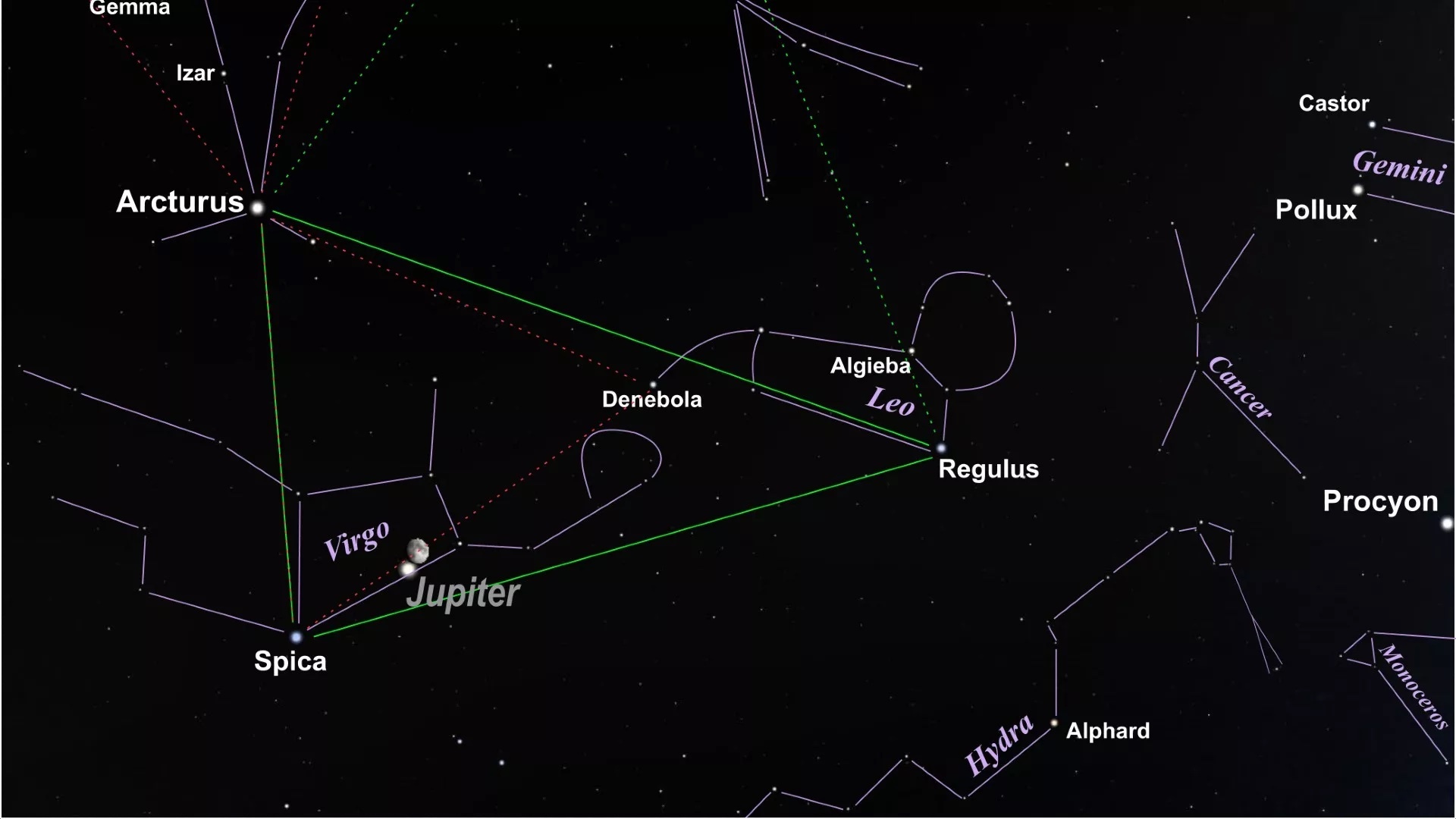

An illustration of the night sky showing the stars of the Spring Triangle: Regulus, Spica, and Arcturus. (Image credit: Elop/Stellarium/Wikimedia Commons)

We're coming down to the home stretch of the spring season and this week, soon after nightfall, two constellations associated with the vernal season are reaching their highest point in the southern part of the sky: Boötes the Herdsman and Virgo the Young Maiden. Zero magnitude Arcturus and first magnitude Spica are, respectively, the brightest stars in these star patterns.

Now, were we to add the second-magnitude star Denebola, from nearby Leo the Lion, we can then trace out a large, nearly perfect equilateral triangle. George Lovi (1939-1993), who for many years penned the "Ramblings" column of Sky & Telescope magazine, called this pattern the "Spring Triangle," perhaps by analogy with the more famous Summer Triangle (made up of the stars Vega, Altair and Deneb).

However, in his book "A Primer for Star-Gazers," Henry Neely (1879-1963) described Arcturus, Spica and Denebola as the "Virgo Triangle." In either case, it's an easy pattern to identify in our current evening sky, both for stargazing novices and for navigators. Unlike the Summer Triangle, however, the Spring (or Virgo) Triangle is nowhere near the Milky Way.

Be that as it may, the Spring Triangle does overlap a vast number of other "milky ways." But more on that later.

If you are hoping to catch a look at the asterisms, stars and constellations of the late spring sky, our guide to the and best binoculars and the best telescopes are a great place to start.

And if you're looking to take photos of the night sky, check out our guide on how to photograph the moon, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

The host constellations

Of the two constellations that supply the two brightest stars of the Spring Triangle, Virgo may not be easy for some beginners to trace out, but it does have Spica as a convenient starting point. Much fainter stars located above and to the west of Spica form a cursive Y-shaped pattern.

To American stargazers, Boötes is the Herdsman or the Bear Driver, an allusion to the way he follows the Big Bear (Ursa Major) around the sky. To the British he is the Ploughman, since he follows the Plough (better known to us here in the U.S. as the Big Dipper) around the sky. Boötes brightest star, the orange-yellow Arcturus, holds the distinction of being not only the brightest star in the Spring Triangle, but the fourth brightest in the entire night sky.

Many pronounce the Herdsman's name incorrectly as Boo-teez, instead of the way it should be, Bo-oh-teez. Take note of the umlaut over the second 'o' (Boötes) to prevent this mispronunciation.

The best way to identify Arcturus and Spica is to first locate the Big Dipper, which is now located almost directly overhead during early evenings. Following along the curve of the Dipper's handle you'll be tracing a broad arc. Eventually, you'll come to Arcturus, quite unmistakable due to its brilliance and eye-catching fiery color. Now continue your imaginary arc past Arcturus and eventually you will arrive at Spica, a bluish star shining with about one-third the radiance of Arcturus.

Just remember this alliterative mnemonic: "Arc to Arcturus ... Speed to Spica."

Most astronomy guides refer to Bootes as resembling a longish kite. To me, however, he has always looked a lot more convincing as an ice cream cone. Considering that we are now at that time of the year when ice cream trucks visit most neighborhoods around suppertime, the ice cream cone reference seems more preferable compared to a kite. In fact, immediately to the left of the cone is a semi-circle of stars which represents the Northern Crown (Corona Borealis.) When giving live presentations in the Space Theater of New York's Hayden Planetarium, I'll point out the Crown as representing a second scoop that somehow slid off the top of the cone.

As to what flavor concoction is in the cone, that's easy. Someone bit off the bottom of the cone (and what kid hasn't done that at least once in their life?) and that's where a glob is poking out.

Since that's where Arcturus is, the flavor is obvious: Orange sorbet or sherbet!

To locate the third star of our Spring Triangle, Denebola, go back to the Big Dipper and pretend that the bowl is filled with water. Now if we were to drill a hole in the bottom of the bowl, all that water would spill straight out toward the south in the direction of Leo the Lion, which is composed of two distinct shapes: Six stars appear to form a large backward question mark marking the head and mane of the Lion, popularly known as the "Sickle." And to the east (left) of the Sickle there is a right triangle of stars which make up the Lion's hindquarters. At the eastern point of this triangle, you'll find Denebola, the "tail" of the Lion.

Connecting Arcturus, Spica and Denebola creates the aforementioned Spring Triangle.

Mind blowing!

Whenever I'm giving a star talk and am looking for an "eye-opening" aspect of the night sky at this time of year, I simply direct my audience to the Spring Triangle. As noted earlier, the famous Summer Triangle is crossed by one of the brightest and star-spangled sections of the Milky Way. In contrast, the region within the Spring Triangle initially appears to be a dull neighborhood both to the naked eye and through binoculars. But just to the east (left) of Denebola is a region that many skywatching guides and astronomy texts often refer to as the "Realm of the Galaxies;" it is here that you will find a veritable treasure trove of numerous star cities.

Literally thousands of galaxies have been photographed here with great observatory telescopes. If you own a good reflecting telescope of at least 6-inch aperture or greater, a sweep of this region will reveal literally dozens of these galaxies appearing as a myriad of faint and fuzzy patches of light. This is the only great cloud of galaxies that is available to the average amateur. And each and every one of these dim blobs is a star city, which likely contains tens, if not hundreds of billions of stars!

Among my personal favorites is NGC (New Galactic Catalog) 4565. Under a dark sky, even a small telescope should show this faint object as a pencil-thin line of haze. In reality, it's a spiral galaxy seen edge-on to our line of sight, with a lane of dark, intergalactic dust that becomes readily apparent in an 8-inch telescope; it resembles two dinner plates with one placed upside down atop the other.

NGC 4565 is believed to be larger and more luminous than the famous Andromeda Galaxy (which itself may contain perhaps a trillion stars), and yet it is accessible only to those using a telescope, chiefly because it's more than 20 times farther away than Andromeda; perhaps as much as 50 million light years distant.

And keep this mind: This cluster or cloud of galaxies is the nearest of the large aggregations of galaxies relative to our own. The best estimates indicate that the majority of these "island universes" are located somewhere between 40 and 70 million light-years from us. So, it is possible that as you run across these pale little patches of light in your telescope, most of which are irregularly shaped, round or elongated in appearance, that you are gazing upon galaxies some of whose light may have started toward the Earth around the time of the extinction of the dinosaurs.

So it is that the Realm of the Galaxies, the nearest and brightest of its kind, transforms the seemingly uninteresting region within the Spring Triangle into one of the most remarkable in the entire sky!

Quelle: SC