NASA’s Dragonfly mission has been authorized to proceed with work on final mission design and fabrication – known as Phase C – during fiscal year (FY) 2024. The agency is postponing formal confirmation of the mission (including its total cost and schedule) until mid-2024, following the release of the FY 2025 President’s Budget Request.

Earlier this year, Dragonfly – a mission to send a rotorcraft to explore Saturn’s moon Titan – passed all the success criteria of its Preliminary Design Review. The Dragonfly team conducted a re-plan of the mission based on expected funding available in FY 2024 and estimate a revised launch readiness date of July 2028. The Agency will officially assess the mission’s launch readiness date in mid-2024 at the Agency Program Management Council.

“The Dragonfly team has successfully overcome a number of technical and programmatic challenges in this daring endeavor to gather new science on Titan,” said Nicola Fox, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at NASA headquarters in Washington. “I am proud of this team and their ability to keep all aspects of the mission moving toward confirmation.”

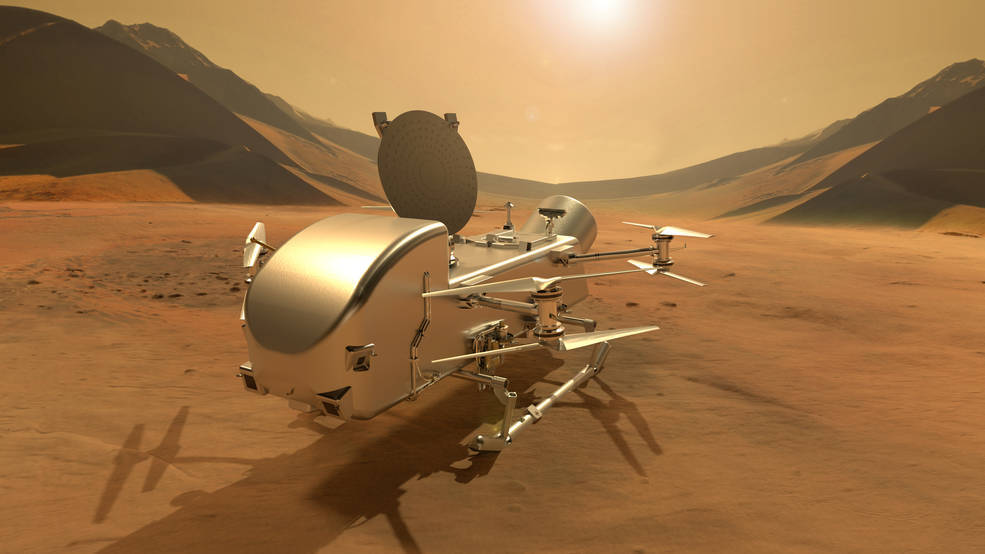

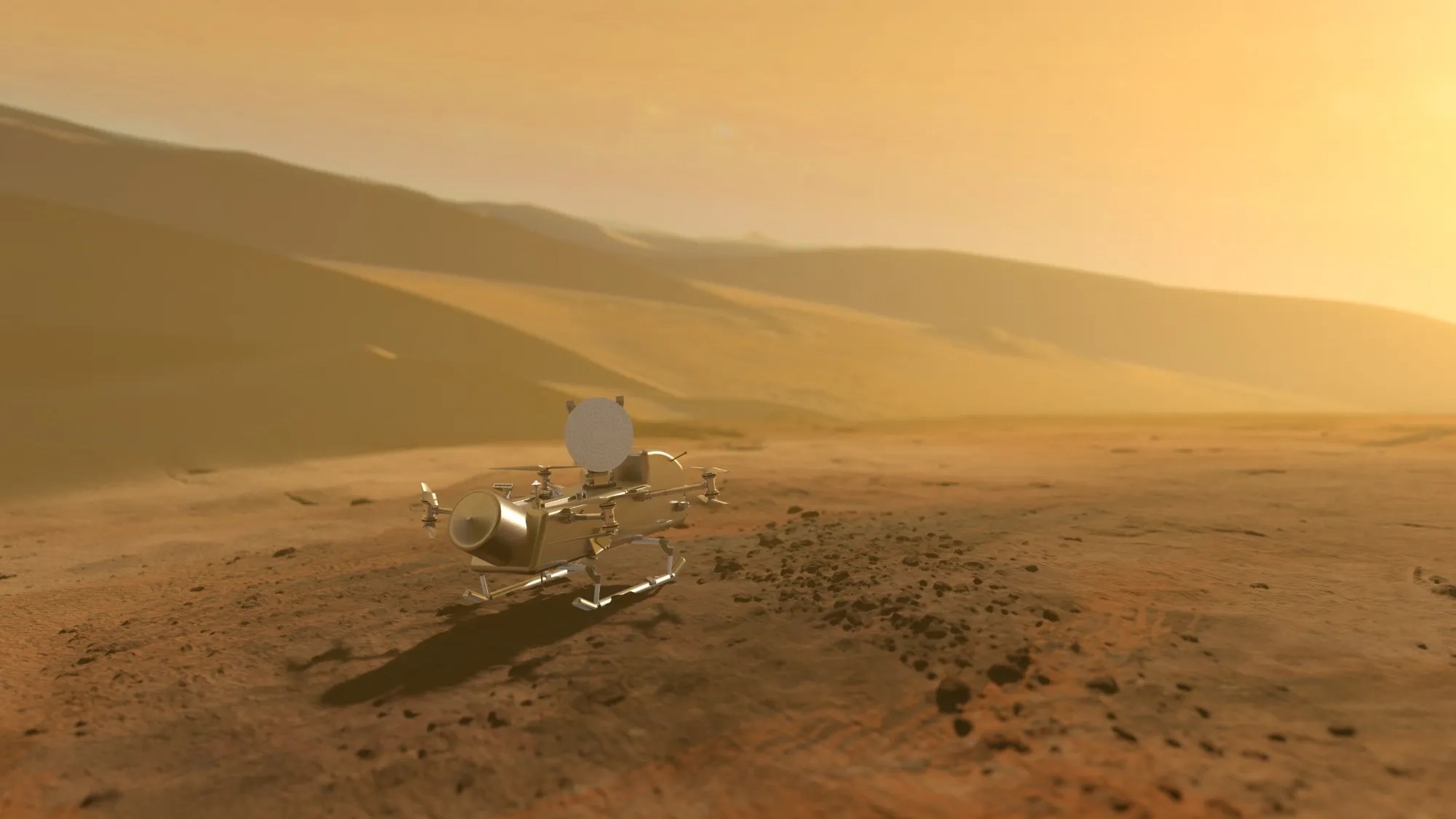

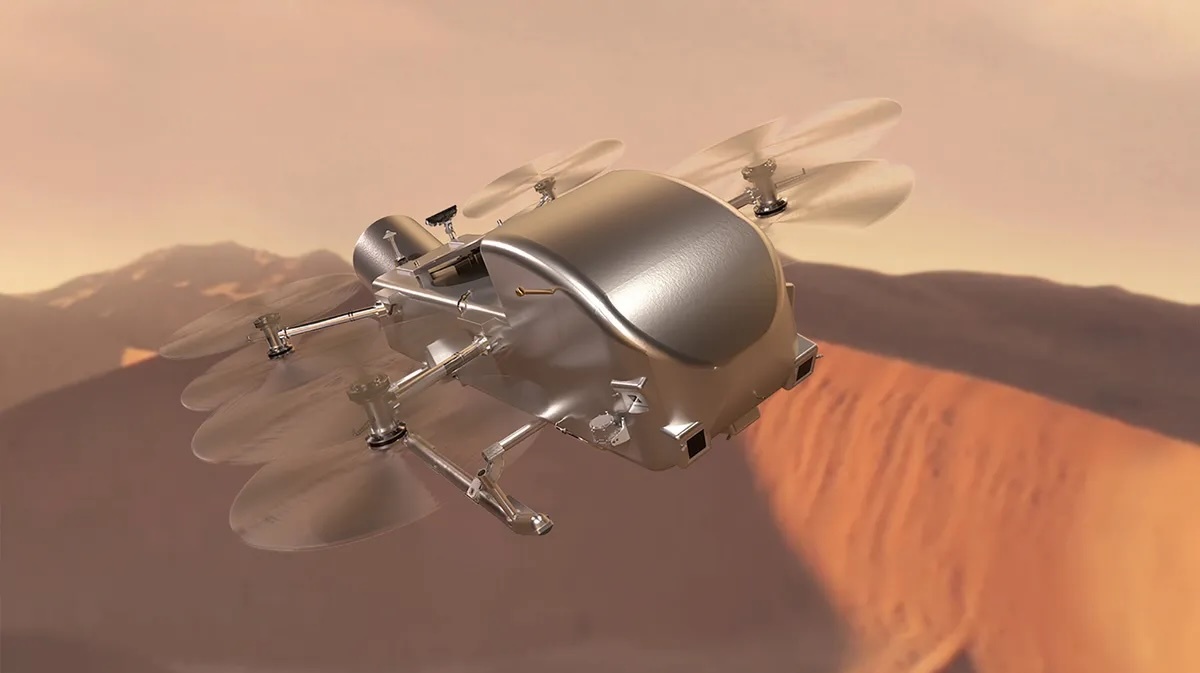

Dragonfly takes a novel approach to planetary exploration, for the first time employing a rotorcraft-lander to travel between and sample diverse sites on Titan. Dragonfly’s goal is to characterize the habitability of the moon’s environment, investigate the progression of prebiotic chemistry in an environment where carbon-rich material and liquid water may have mixed for an extended period, and even search for chemical indications of whether water-based or hydrocarbon-based life once existed on Titan.

Dragonfly is being designed and built under the direction of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, which manages the mission for NASA. The team includes key partners at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland; Lockheed Martin Space in Littleton, Colorado; Sikorsky, a Lockheed Martin company; NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California; NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia; Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania; Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego, California; Honeybee Robotics in Pasadena, California; NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California; CNES (Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales), the French space agency, in Paris, France; DLR (German Aerospace Center) in Cologne, Germany; and JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) in Tokyo, Japan. Dragonfly is the fourth mission in NASA’s New Frontiers Program, managed by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the Science Mission Directorate.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 27.11.2024

.

NASA's nuclear-powered Dragonfly helicopter will ride a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket toward Saturn moon Titan

The Dragonfly rotorcraft will ride a Falcon Heavy into space in July 2028, kicking off a six-year journey to Titan.

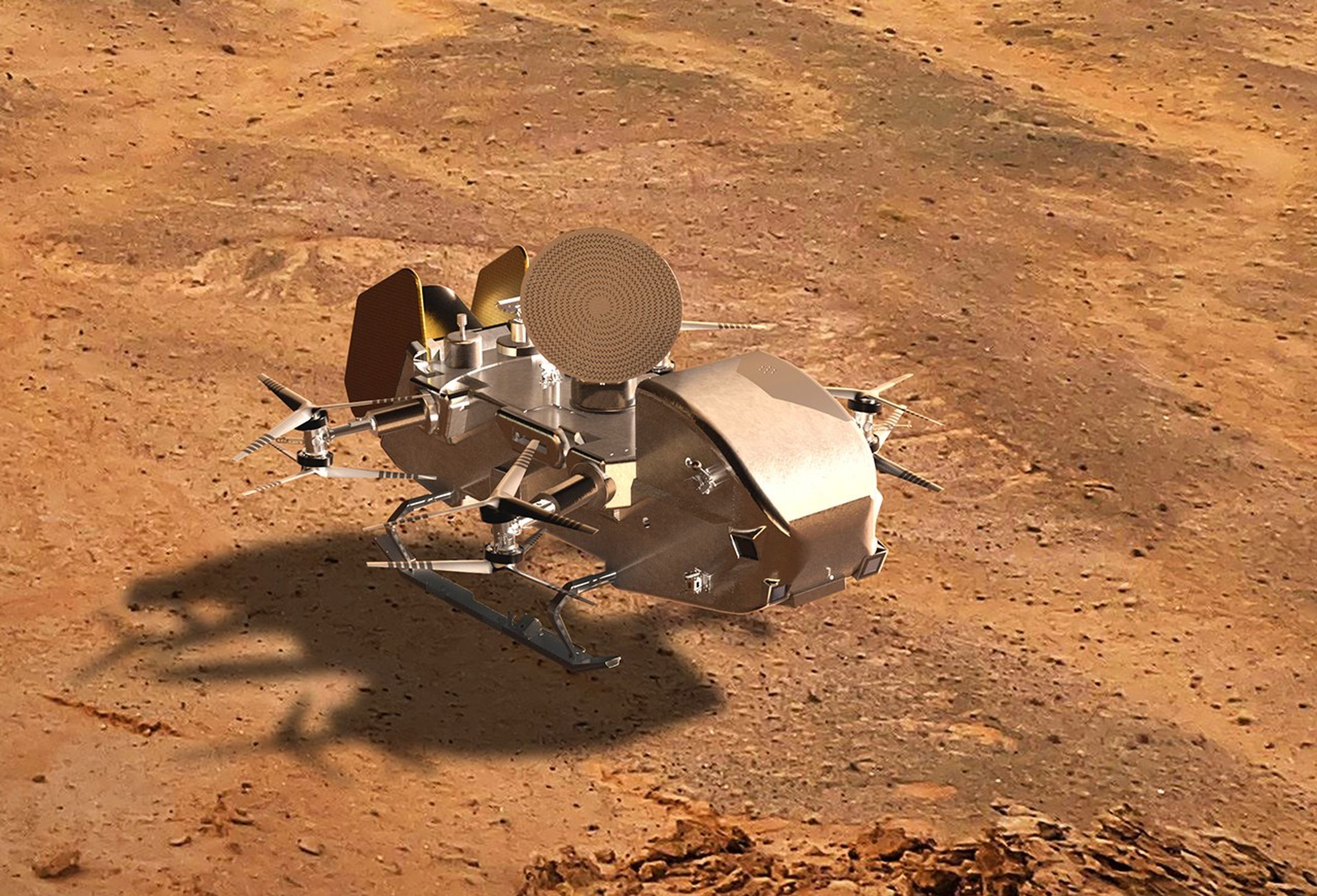

An illustration of NASA's Dragonfly rotorcraft soaring in the skies of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. (Image credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben)

SpaceX's powerful Falcon Heavy rocket will launch yet another high-profile NASA science mission.

The agency announced today (Nov. 25) that it has picked the Falcon Heavy to loft Dragonfly, a $3.35 billion mission that will investigate the life-hosting potential of Saturn's huge moon Titan. The burly rocket also launched NASA's Psyche asteroid probe and Europa Clipper spacecraft, in October 2023 and October 2024, respectively.

The Dragonfly contract is a firm, fixed-price deal with a value of nearly $257 million, "which includes launch services and other mission-related costs," NASA officials wrote in an update this afternoon.

If all goes according to plan, Falcon Heavy will launch the car-sized Dragonfly rotorcraft during a three-week window in July 2028. The spacecraft will then spend six years making its way to Titan, the second-largest moon in the solar system (after Jupiter's Ganymede).

Titan's size isn't its only intriguing characteristic. The frigid satellite hosts seas and lakes of hydrocarbons, making it the only body beyond Earth known to host stable liquids on its surface. In addition, organic compounds, the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it, are common on the world.

Some scientists therefore think Titan may be capable of supporting life — perhaps on its alien surface or in its suspected subterranean ocean of liquid water. Dragonfly is designed to investigate this question, and to shed light on a little-studied world more generally.

"With contributions from partners around the globe, Dragonfly’s scientific payload will characterize the habitability of Titan's environment, investigate the progression of prebiotic chemistry on Titan, where carbon-rich material and liquid water may have mixed for an extended period, and search for chemical indications of whether water-based or hydrocarbon-based life once existed on Saturn’s moon," NASA officials wrote in today's update.

The nuclear-powered rotorcraft will operate for about 2.5 Earth years on Titan's surface, flitting from place to place to get an in-depth look at a variety of landscapes.

Dragonfly has experienced delays and cost increases during its development. When NASA originally selected the mission in 2019, for example, its cost was capped at $1 billion, and launch was targeted for 2027.

Such issues are far from uncommon on ambitious exploration efforts such as Dragonfly. And the mission has made significant progress recently; it remains on track for its current 2028 launch target, NASA announced earlier this year.

Falcon Heavy is the second-most-powerful rocket currently in operation, after NASA's Space Launch System moon rocket (though SpaceX's Starship megarocket will claim the title when it comes online). Falcon Heavy has launched 11 times to date, most recently sending Europa Clipper toward Jupiter's ocean moon Europa on Oct. 14.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 24.05.2025

.

NASA’s Dragonfly Mission Sets Sights on Titan’s Mysteries

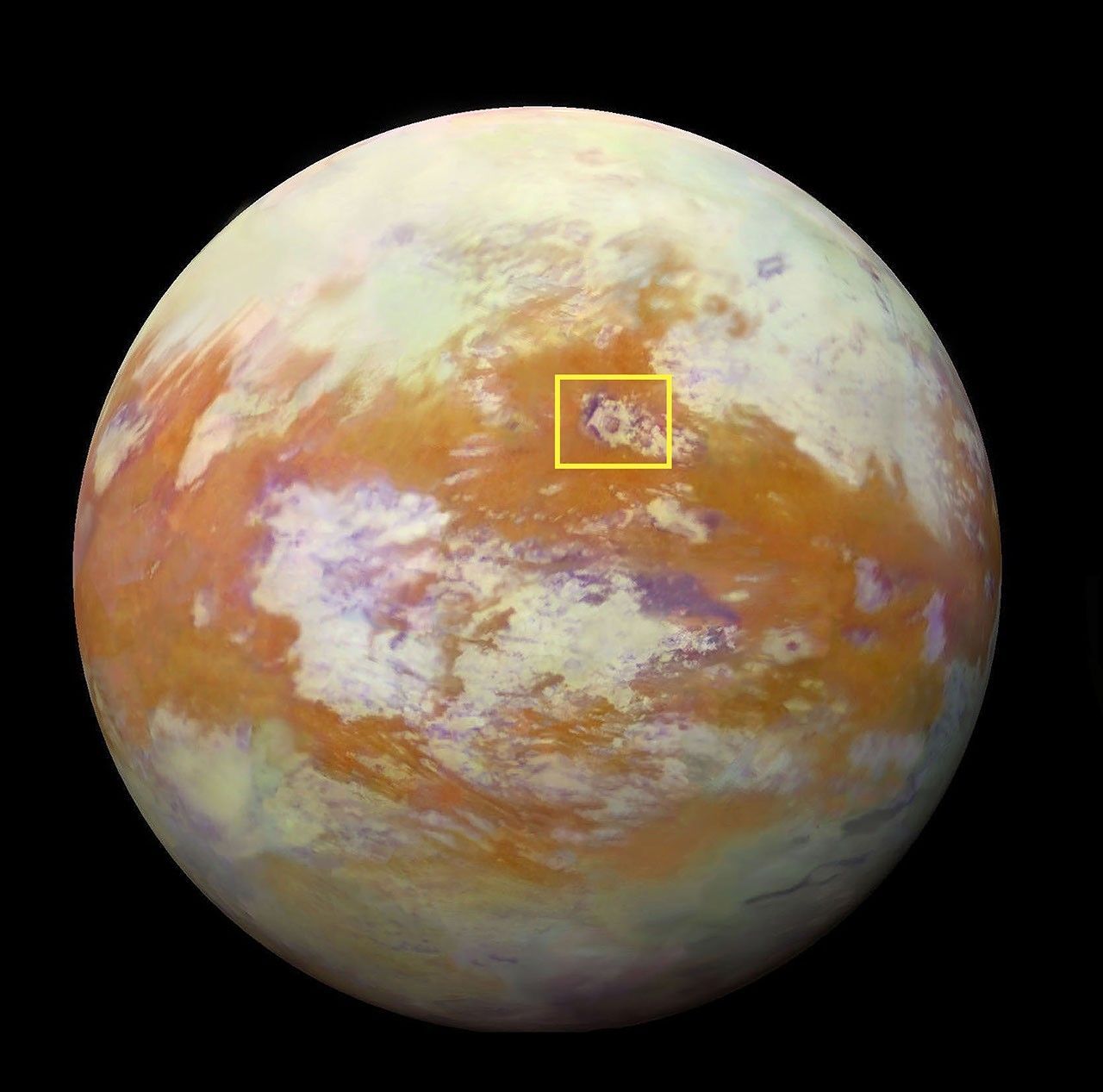

When it descends through the thick golden haze on Saturn’s moon Titan, NASA’s Dragonfly rotorcraft will find eerily familiar terrain. Dunes wrap around Titan’s equator. Clouds drift across its skies. Rain drizzles. Rivers flow, forming canyons, lakes and seas.

But not everything is as familiar as it seems. At minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit, the dune sands aren’t silicate grains but organic material. The rivers, lakes and seas hold liquid methane and ethane, not water. Titan is a frigid world laden with organic molecules.

Yet Dragonfly, a car-sized rotorcraft set to launch no earlier than 2028, will explore this frigid world to potentially answer one of science’s biggest questions: How did life begin?

Seeking answers about life in a place where it likely can’t survive seems odd. But that’s precisely the point.

“Dragonfly isn’t a mission to detect life — it’s a mission to investigate the chemistry that came before biology here on Earth,” said Zibi Turtle, principal investigator for Dragonfly and a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “On Titan, we can explore the chemical processes that may have led to life on Earth without life complicating the picture.”

On Earth, life has reshaped nearly everything, burying its chemical forebears beneath eons of evolution. Even today’s microbes rely on a slew of reactions to keep squirming.

“You need to have gone from simple to complex chemistry before jumping to biology, but we don’t know all the steps,” Turtle said. “Titan allows us to uncover some of them.”

Titan is an untouched chemical laboratory where all the ingredients for known life — organics, liquid water and an energy source — have interacted in the past. What Dragonfly uncovers will illuminate a past since erased on Earth and refine our understanding of habitability and whether the chemistry that sparked life here is a universal rule — or a wonderous cosmic fluke.

Before NASA’s Cassini-Huygens mission, researchers didn't know just how rich Titan is in organic molecules. The mission’s data, combined with laboratory experiments, revealed a molecular smorgasbord — ethane, propane, acetylene, acetone, vinyl cyanide, benzene, cyanogen, and more.

These molecules fall to the surface, forming thick deposits on Titan’s ice bedrock. Scientists believe life-related chemistry could start there — if given some liquid water, such as from an asteroid impact.

Enter Selk crater, a 50-mile-wide impact site. It’s a key Dragonfly destination, not only because it’s covered in organics, but because it may have had liquid water for an extended time.

The impact that formed Selk melted the icy bedrock, creating a temporary pool that could have remained liquid for hundreds to thousands of years under an insulating ice layer, like winter ponds on Earth. If a natural antifreeze like ammonia were mixed in, the pool could have remained unfrozen even longer, blending water with organics and the impactor’s silicon, phosphorus, sulfur and iron to form a primordial soup.

“It’s essentially a long-running chemical experiment,” said Sarah Hörst, an atmospheric chemist at Johns Hopkins University and co-investigator on Dragonfly’s science team. “That’s why Titan is exciting. It’s a natural version of our origin-of-life experiments — except it’s been running much longer and on a planetary scale.”

For decades, scientists have simulated Earth’s early conditions, mixing water with simple organics to create a “prebiotic soup” and jumpstarting reactions with an electrical shock. The problem is time. Most tests last weeks, maybe months or years.

The melt pools at Selk crater, however, possibly lasted tens of thousands of years. Still shorter than the hundreds of millions of years it took life to emerge on Earth, but potentially enough time for critical chemistry to occur.

“We don’t know if Earth life took so long because conditions had to stabilize or because the chemistry itself needed time,” Hörst said. “But models show that if you toss Titan’s organics into water, tens of thousands of years is plenty of time for chemistry to happen.”

Dragonfly will test that theory. Landing near Selk, it will fly from site to site, analyzing the surface chemistry to investigate the frozen remains of what could have been prebiotic chemistry in action.

Morgan Cable, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and co-investigator on Dragonfly, is particularly excited about the Dragonfly Mass Spectrometer (DraMS) instrument. Developed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, with a key subsystem provided by the CNES (Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales), DraMS will search for indicators of complex chemistry.

“We’re not looking for exact molecules, but patterns that suggest complexity,” Cable said. On Earth, for example, amino acids — fundamental to proteins — appear in specific patterns. A world without life would mainly manufacture the simplest amino acids and form fewer complex ones.

Generally, Titan isn’t regarded as habitable; it’s too cold for the chemistry of life as we know it to occur, and there’s is no liquid water on the surface, where the organics and likely energy sources exist.

Still, scientists have assumed that if a place has life’s ingredients and enough time, complex chemistry — and eventually life — should emerge. If Titan proves otherwise, it may mean we’ve misunderstood something about life’s start and it may be rarer than we thought.

“We won’t know how easy or difficult it is for these chemical steps to occur if we don’t go, so we need to go and look,” Cable said. “That’s the fun thing about going to a world like Titan. We’re like detectives with our magnifying glasses, looking at everything and wondering what this is.”

Dragonfly is being designed and built under the direction of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), which manages the mission for NASA. The team includes key partners at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Dragonfly is managed by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 11.01.2026

.

Flight Engineers Give NASA’s Dragonfly Lift

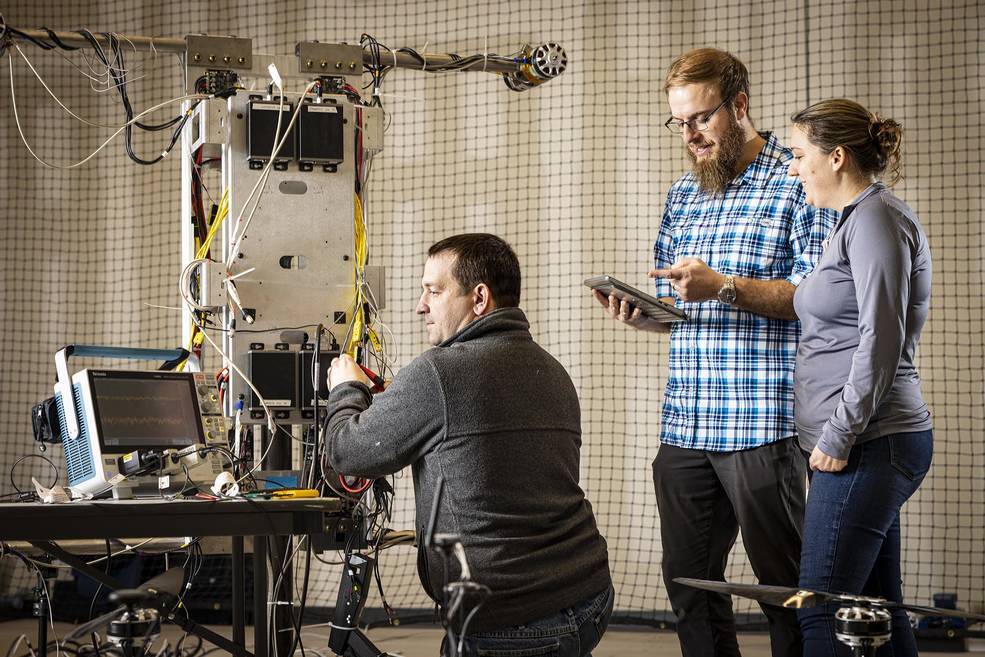

In sending a car-sized rotorcraft to explore Saturn’s moon Titan, NASA’s Dragonfly mission will undertake an unprecedented voyage of scientific discovery. And the work to ensure that this first-of-its-kind project can fulfill its ambitious exploration vision is underway in some of the nation’s most advanced space simulation and testing laboratories.

Set for launch in in 2028, the Dragonfly rotorcraft is being designed and built at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, with contributions from organizations around the world. On arrival in 2034, Dragonfly will exploit Titan’s dense atmosphere and low gravity to fly to dozens of locations, exploring varied environments from organic equatorial dunes to an impact crater where liquid water and complex organic materials essential to life (at least as we know it) may have existed together.

Aerodynamic testing

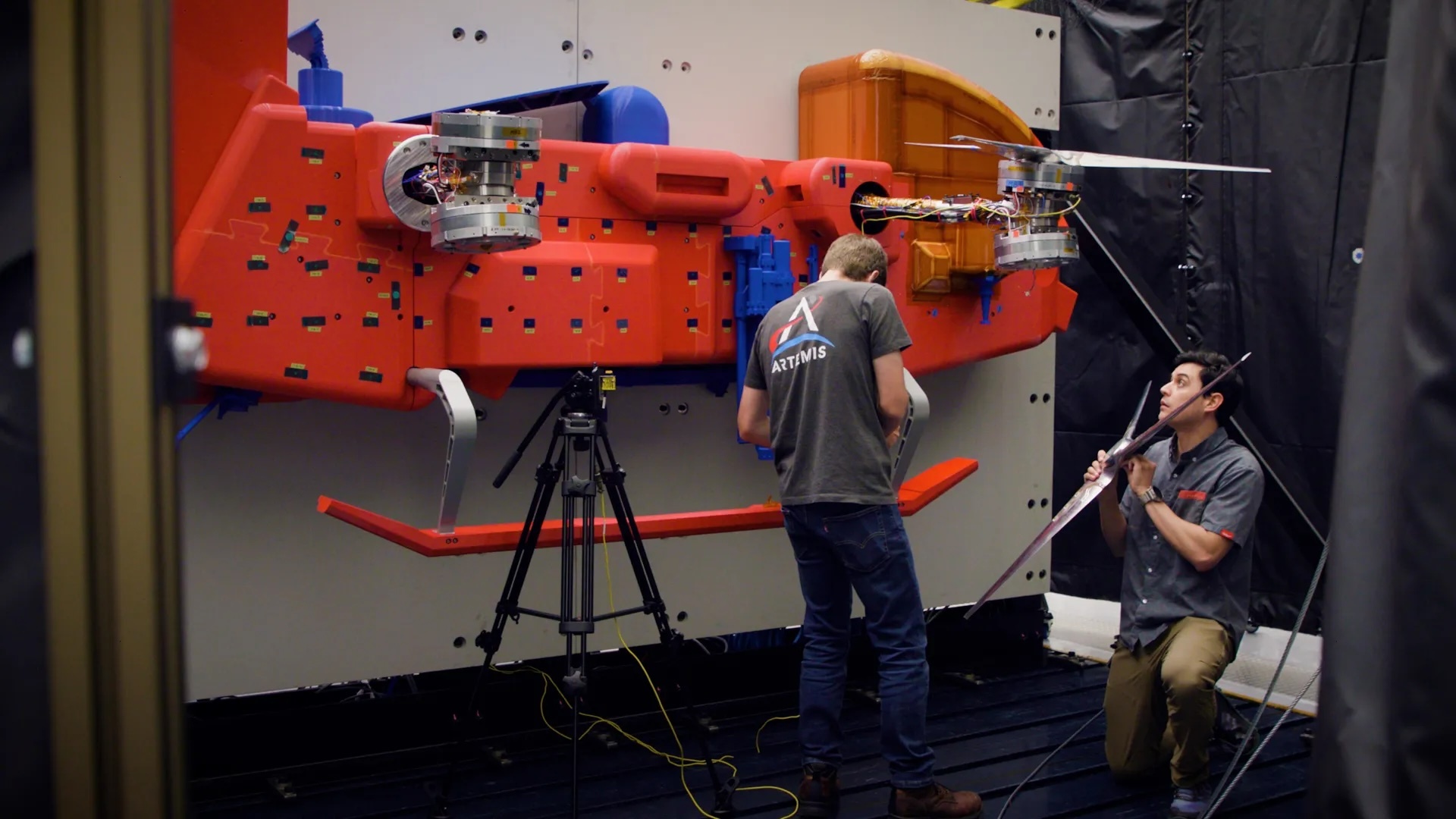

When full rotorcraft integration and testing begins in February, the team will tap into a trove of data gathered through critical technical trials conducted over the past three years, including, most recently, two campaigns at the Transonic Dynamics Tunnel (TDT) facility at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

The TDT is a versatile 16-foot-high, 16-foot-wide, 20-foot-long testing hub that has hosted studies for NASA, the Department of War, the aircraft industry and an array of universities.

Over five weeks, from August into September, the team evaluated the performance of Dragonfly’s rotor system – which provides the lift for the lander to fly and enables it to maneuver – in Titan-like conditions, looking at aeromechanical performance factors such as stress on the rotor arms, and effects of vibration on the rotor blades and lander body. In late December, the team also wrapped up a set of aerodynamics tests on smaller-scale Dragonfly rotor models in the TDT.

“When Dragonfly enters the atmosphere at Titan and parachutes deploy after the heat shield does its job, the rotors are going to have to work perfectly the first time,” said Dave Piatak, branch chief for aeroelasticity at NASA Langley. “There’s no room for error, so any concerns with vehicle structural dynamics or aerodynamics need to be known now and tested on the ground. With the Transonic Dynamics Tunnel here at Langley, NASA offers just the right capability for the Dragonfly team to gather this critical data.”

Critical parts

In his three years as an experimental machinist at APL, Cory Pennington has crafted parts for projects dispatched around the globe. But fashioning rotors for a drone to explore another world in our solar system? That was new – and a little daunting.

“The rotors are some of the most important parts on Dragonfly,” Pennington said. “Without the rotors, it doesn’t fly – and it doesn’t meet its mission objectives at Titan.”

Pennington and team cut Dragonfly’s first rotors on Nov. 1, 2024. They refined the process as they went: starting with waterjet paring of 1,000-pound aluminum blocks, followed by rough machining, cover fitting, vent-hole drilling and hole-threading. After an inspection, the parts were cleaned, sent out for welding and returned for final finishing.

“We didn’t have time or materials to make test parts or extras, so every cut had to be right the first time,” Pennington said, adding that the team also had to find special tools and equipment to accommodate some material changes and design tweaks.

The team was able to deliver the parts a month early. Engineers set up and spin-tested the rotors at APL – attached to a full-scale model representing half of the Dragonfly lander – before transporting the entire package to the TDT at NASA Langley in late July.

“On Titan, we’ll control the speeds of Dragonfly’s different rotors to induce forward flight, climbs, descents and turns,” said Felipe Ruiz, lead Dragonfly rotor engineer at APL.

“It’s a complicated geometry going to a flight environment that we are still learning about. So the wind tunnel tests are one of the most important venues for us to demonstrate the design.”

And the rotors passed the tests.

“Not only did the tests validate the design team’s approach, we’ll use all that data to create high-fidelity representations of loads, forces and dynamics that help us predict Dragonfly’s performance on Titan with a high degree of confidence,” said Rick Heisler, wind tunnel test lead from APL.

Next, the rotors will undergo fatigue and cryogenic trials under simulated Titan conditions, where the temperature is minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 178 degrees Celsius), before building the actual flight rotors.

“We’re not just cutting metal — we’re fabricating something that’s going to another world,” Pennington said. “It’s incredible to know that what we build will fly on Titan.”

Collaboration, innovation

Elizabeth “Zibi” Turtle, Dragonfly principal investigator at APL, says the latest work in the TDT demonstrates the mission’s innovation, ingenuity and collaboration across government and industry.

“The team worked well together, under time pressure, to develop solutions, assess design decisions, and execute fabrication and testing,” she said. “There’s still much to do between now and our launch in 2028, but everyone who worked on this should take tremendous pride in these accomplishments that make it possible for Dragonfly to fly on Titan.”

Dragonfly has been a collaborative effort from the start. Kenneth Hibbard, mission systems engineer from APL, cites the vertical-lift expertise of Penn State University on the initial rotor design, aero-related modeling and analysis, and testing support in the TDT, as well as NASA Langley’s 14-by-22-foot Subsonic Tunnel. Sikorsky Aircraft of Connecticut has also supported aeromechanics and aerodynamics testing and analysis, as well as flight hardware modeling and simulation.

The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, leads the Dragonfly mission for NASA in collaboration with several NASA centers, industry partners, academic institutions and international space agencies. Elizabeth “Zibi” Turtle of APL is the principal investigator. Dragonfly is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, managed by the Planetary Missions Program Office at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 12.03.2026

.

NASA’s Dragonfly Mission Begins Rotorcraft Integration, Testing Stage

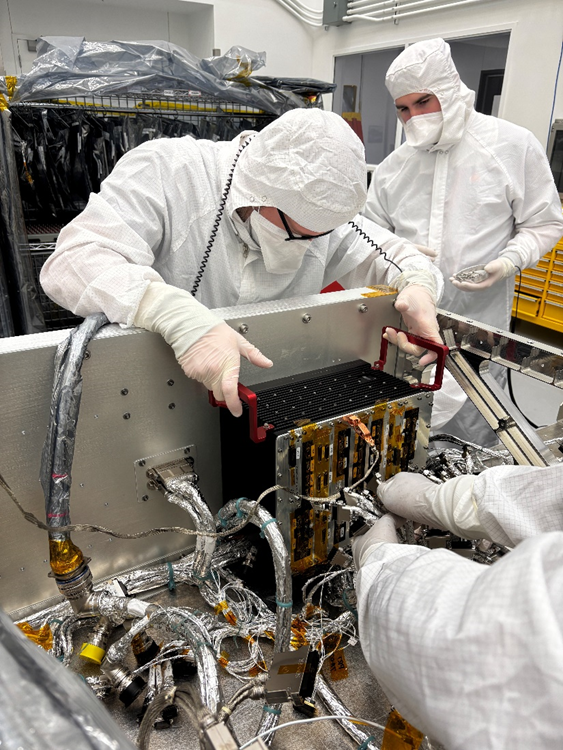

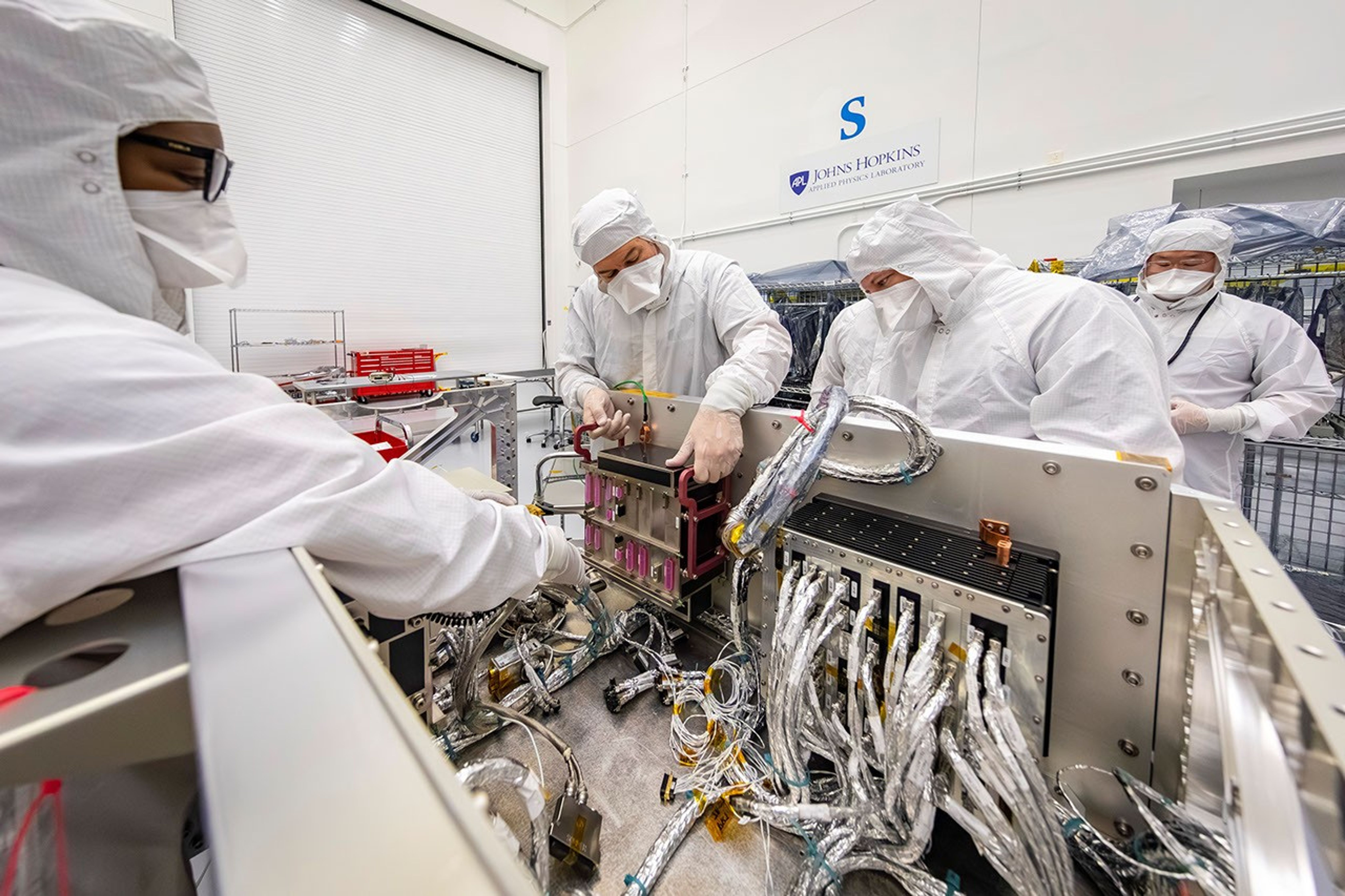

NASA Dragonfly’s integration and testing – the activities involved in assembling the mission’s rotorcraft lander and testing it for the rigors of launch and extreme conditions of space – is officially underway in clean rooms and control rooms at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

In partnership with teams across government, industry and academia, APL is building the car-sized, nuclear-powered drone for NASA. Dragonfly is scheduled to launch no earlier than 2028 for a six-year voyage to Saturn’s moon Titan, where it will explore a range of diverse sites to study the chemistry, geology, and atmosphere of the terrestrial moon and ultimately advance our understanding of life’s chemical origins.

Primary activities during the first weeks of this effort included power and functional testing on two critical components: the Integrated Electronics Module (IEM) and the Power Switching Units (PSUs). Think of the IEM as Dragonfly’s “brain,” containing the spacecraft’s core avionics (such as command and data handling, guidance and navigation, and communications) in a single space-saving and power-efficient box. The IEM and both PSUs were connected to Dragonfly’s wiring system and passed their first power-service checks.

“This milestone essentially marks the birth of our flight system,” said Elizabeth Turtle, Dragonfly principal investigator from APL. “Building a first-of-its kind vehicle to fly across another ocean world in our solar system pushes us to the edge of what’s possible, but that’s exactly why this stage is so exciting. The team is doing an outstanding job, and every component we install and every test we run brings us one step closer to launching Dragonfly to Titan.”

Much work has led up to this point. The aeroshell and cruise-stage assemblies are moving forward with integration and testing at Lockheed Martin Space in Littleton, Colorado. The team completed a thorough aerodynamic test series in the wind tunnels of NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. Testing continues in the Titan Chamber at APL of the foam coating that will insulate the rotorcraft from Titan’s frigid temperatures. The science payload is coming together at locations around the country and internationally. The flight radio has been delivered, and additional flight systems are scheduled for delivery and testing within the next six months.

Dragonfly integration and testing will continue at APL through this year and into early 2027, when system-level testing is planned at Lockheed Martin. Late next year, the lander returns to APL for final space-environment testing before heading to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida in spring 2028 for launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket that summer.

“Starting integration and testing is a huge milestone for the Dragonfly team,” said Annette Dolbow, the Dragonfly integration and test lead at APL. “We’ve spent years designing and refining this amazing rotorcraft on computer screens and in laboratories, and now we get to bring all those elements together and transform Dragonfly into an actual flight system.”

Quelle: NASA