29.01.2023

NASA’s Juno Team Assessing Camera After 48th Flyby of Jupiter

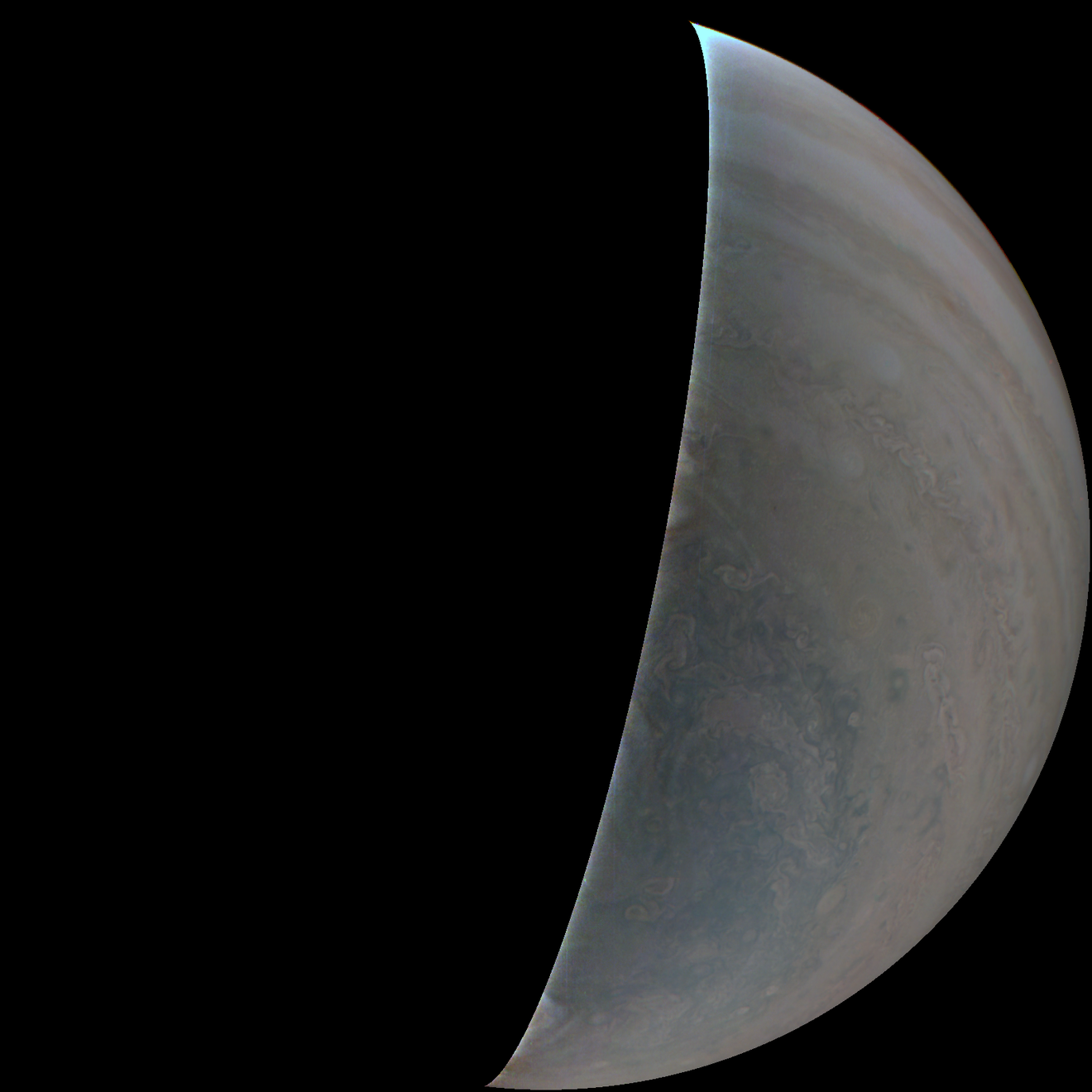

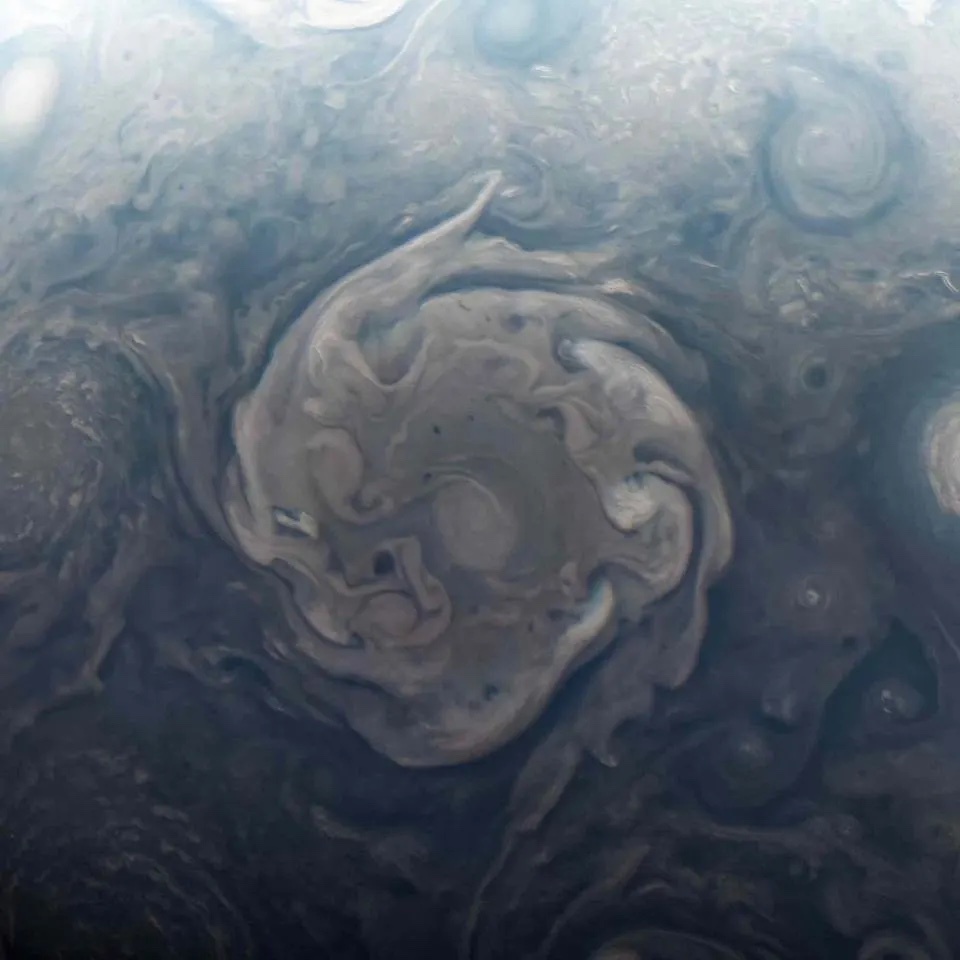

Jupiter’s southern hemisphere was captured by the JunoCam imager aboard NASA’s Juno orbiter after the camera returned to normal operation following an issue that occurred during its Jan. 22, 2023, flyby. The image was acquired at an altitude of 77,507 miles (124,735 kilometers) at a resolution of 52 miles (84 kilometers) per pixel.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS

Engineering data is being evaluated to determine why the majority of images taken by the solar-powered orbiter’s JunoCam were not acquired.

The JunoCam imager aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft did not acquire all planned images during the orbiter’s most recent flyby of Jupiter on Jan. 22. Data received from the spacecraft indicates that the camera experienced an issue similar to one that occurred on its previous close pass of the gas giant last month, when the team saw an anomalous temperature rise after the camera was powered on in preparation for the flyby.

However, on this new occasion the issue persisted for a longer period of time (23 hours compared to 36 minutes during the December close pass), leaving the first 214 JunoCam images planned for the flyby unusable. As with the previous occurrence, once the anomaly that caused the temperature rise cleared, the camera returned to normal operation and the remaining 44 images were of good quality and usable.

The mission team is evaluating JunoCam engineering data acquired during the two recent flybys – the 47th and 48th of the mission – and is investigating the root cause of the anomaly and mitigation strategies. JunoCam will remain powered on for the time being and the camera continues to operate in its nominal state.

JunoCam is a color, visible-light camera designed to capture pictures of Jupiter’s cloud tops. It was included on the spacecraft specifically for purposes of public engagement but has proven to be important for science investigations also. The camera was originally designed to operate in Jupiter’s high-energy particle environment for at least seven orbits but has survived far longer.

The spacecraft will make its 49th pass of Jupiter on March 1.

More About the Mission

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott J. Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 2.02.2023

.

NASA loses more than 200 Jupiter photos after Juno probe camera glitch

Juno's JunoCam imager suffered a similar problem last month as well.

An image of Jupiter captured by JunoCam during the mission's 48th flyby. (Image credit: NASA/JPL/SwRI/MSSS/Gerald Eichstädt/Thomas Thomopoulos CC BY)

For the second flyby in a row, a key camera studying Jupiter has struggled to snap photos as usual.

NASA's Juno spacecraft launched in 2011 and arrived at Jupiter in 2016; since then, it has made nearly 50 flybys of the largest planet in our solar system and caught valuable glimpses of Jupiter's large moons, each a strange world in its own right. But during the spacecraft's most recent flyby, on Jan. 22, the camera was able to capture only about one-fifth of the planned images.

A similar issue occurred on the previous flyby, in December; mission personnel believe that the camera glitch stems from the camera reaching an unusually high temperature and are continuing to troubleshoot the issue, according to a statement.

Shortly after the Dec. 14 flyby, Juno experienced a memory issue that sent the spacecraft into safe mode, delaying the transmission of data to Earth, according to a statement at the time. Juno bounced back smoothly and most of the data reached Earth safely, but JunoCam struggled early in the flyby.

The camera had been directed to capture 90 images during the December flyby, but the first four photos turned out badly. The mission team determined that when JunoCam turned on, temperatures rose enough to interfere with photography and the instrument had cooled off by the end of those first four images.

But now, the issue seems to have recurred, this time for longer — 23 hours rather than 36 minutes, according to NASA. This time, the glitch left 214 images unusable, with only 44 decent images returned after the instrument cooled sufficiently.

"The mission team is evaluating JunoCam engineering data acquired during the two recent flybys — the 47th and 48th of the mission — and is investigating the root cause of the anomaly and mitigation strategies," NASA officials wrote. "JunoCam will remain powered on for the time being and the camera continues to operate in its nominal state."

Juno's next flyby will occur on March 1.

Mission personnel considered launching Juno without a camera onboard, since the spacecraft's science goals didn't require such an instrument, but the agency decided to add JunoCam as a public outreach project. The color camera snaps photos of the tops of Jupiter's dynamic clouds, with the public suggesting where to aim and processing the collected images.

And JunoCam wasn't guaranteed to last even this long, according to NASA: It was designed to survive just seven passes through the dangerous environment surrounding Jupiter.

Juno itself is also operating beyond its primary mission, which ended in July 2021; it is currently expected to continue as long as September 2025.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 17.05.2023

.

NASA’s Juno Mission Getting Closer to Jupiter’s Moon Io

The gas giant orbiter has flown over 510 million miles and also documented close encounters with three of Jupiter’s four largest moons.

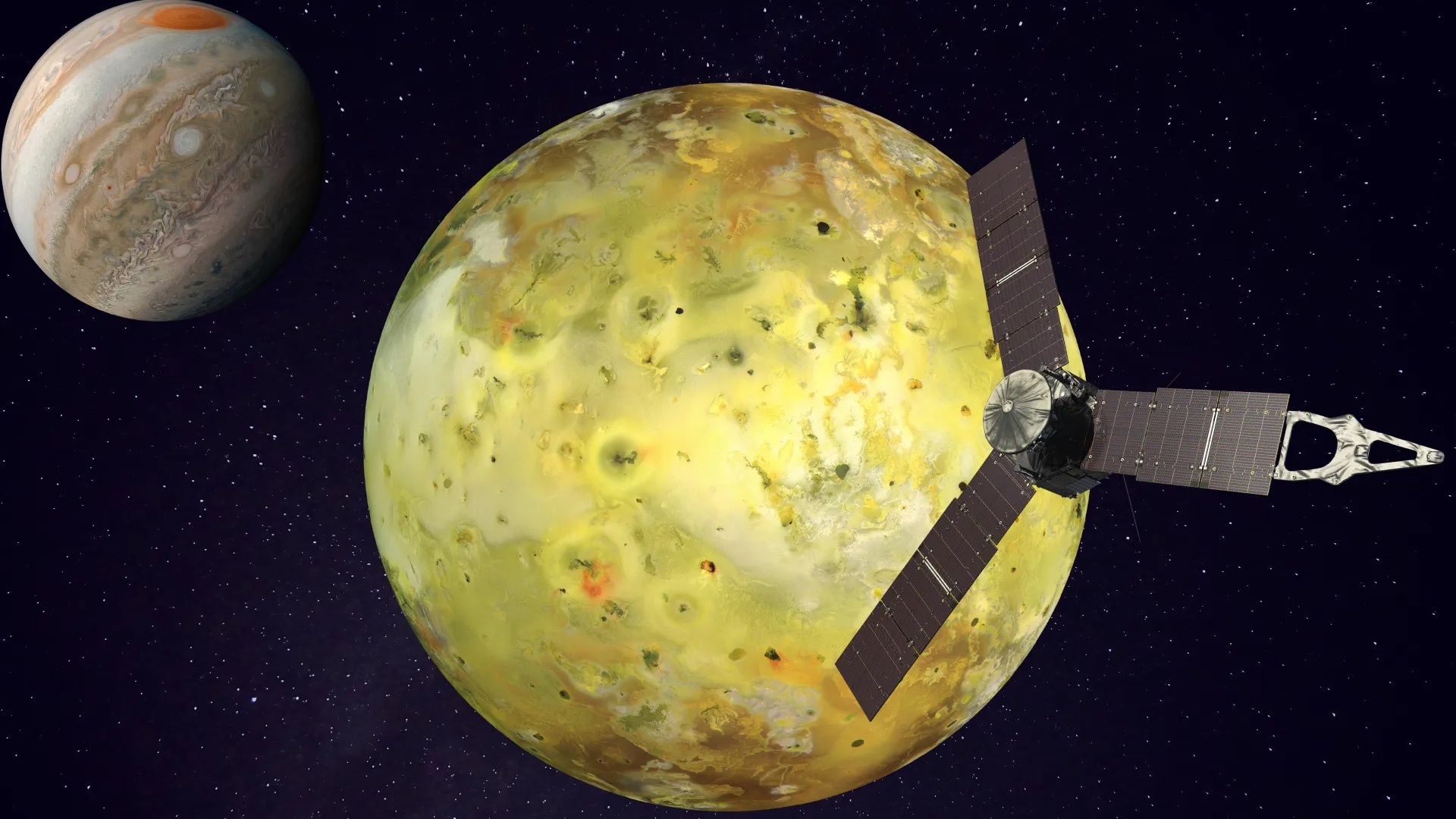

NASA’s Juno spacecraft will fly past Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io on Tuesday, May 16, and then the gas giant itself soon after. The flyby of the Jovian moon will be the closest to date, at an altitude of about 22,060 miles (35,500 kilometers). Now in the third year of its extended mission to investigate the interior of Jupiter, the solar-powered spacecraft will also explore the ring system where some of the gas giant’s inner moons reside.

To date, Juno has performed 50 flybys of Jupiter and also collected data during close encounters with three of the four Galilean moons – the icy worlds Europa and Ganymede, and fiery Io.

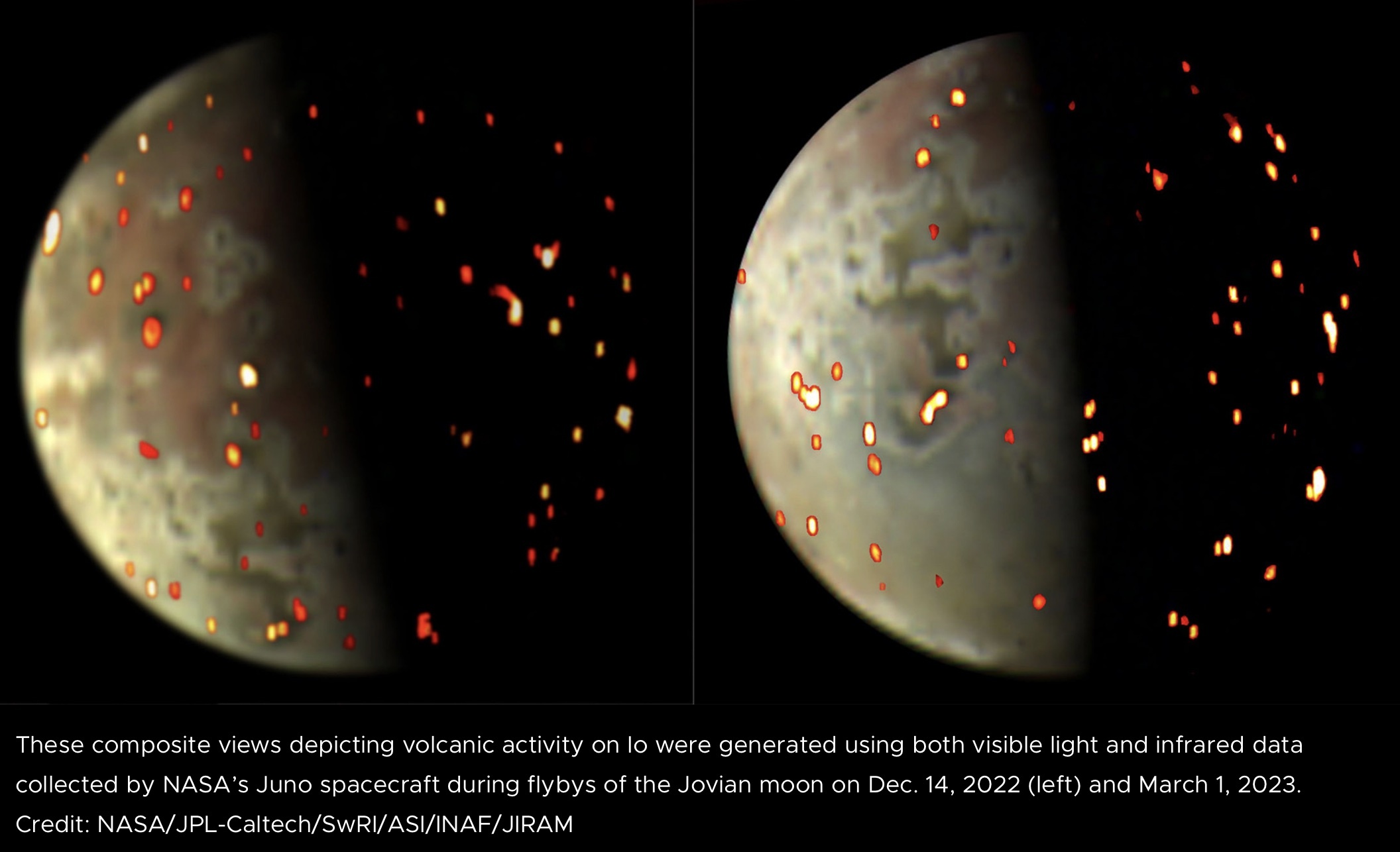

“Io is the most volcanic celestial body that we know of in our solar system,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “By observing it over time on multiple passes, we can watch how the volcanoes vary – how often they erupt, how bright and hot they are, whether they are linked to a group or solo, and if the shape of the lava flow changes.”

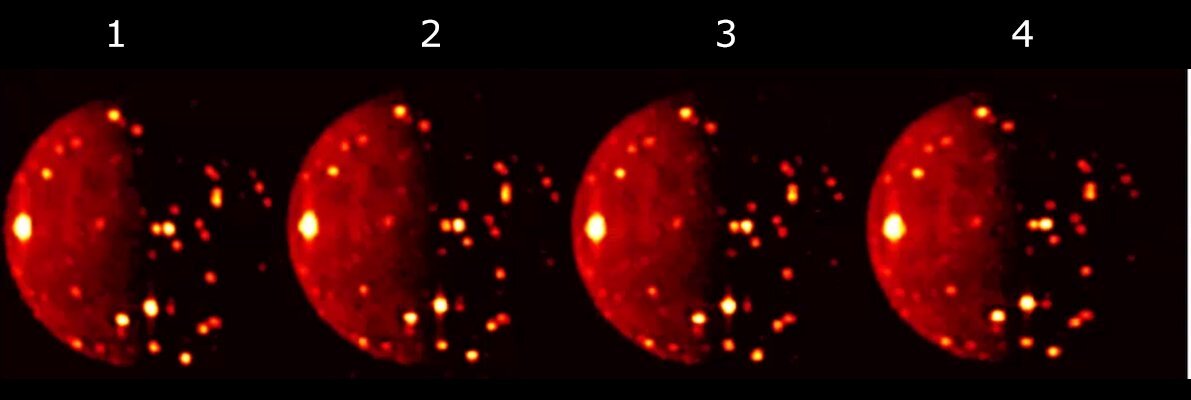

These infrared views of volcanic activity of Jupiter’s moon Io were collected by the JIRAM (Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper) instrument aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft during a flyby of the moon on Oct. 16, 2021.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM

Slightly larger than Earth’s moon, Io is a world in constant torment. Not only is the biggest planet in the solar system forever pulling at it gravitationally, but so are its Galilean siblings – Europa and the biggest moon in the solar system, Ganymede. The result is that Io is continuously stretched and squeezed, actions linked to the creation of the lava seen erupting from its many volcanoes.

While Juno was designed to study Jupiter, its many sensors have additionally provided a wealth of data on the planet’s moons. Along with its visible light imager JunoCam, the spacecraft’s JIRAM (Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper), SRU (Stellar Reference Unit), and MWR (Microwave Radiometer) will be studying Io’s volcanoes and how volcanic eruptions interact with Jupiter’s powerful magnetosphere and auroras.

This downloadable graphic contains 50 image highlights from NASA’s Juno mission to Jupiter. Juno completed its 50th close pass of the gas giant on April 8, 2023.

“We are entering into another amazing part of Juno’s mission as we get closer and closer to Io with successive orbits. This 51st orbit will provide our closest look yet at this tortured moon,” said Bolton. “Our upcoming flybys in July and October will bring us even closer, leading up to our twin flyby encounters with Io in December of this year and February of next year, when we fly within 1,500 kilometers of its surface. All of these flybys are providing spectacular views of the volcanic activity of this amazing moon. The data should be amazing.”

A “Half-Century” at Jupiter

During its flybys of Jupiter, Juno has zoomed low over the planet’s cloud tops – as close as about 2,100 miles (3,400 kilometers). Approaching the planet from over the north pole and exiting over the south during these flybys, the spacecraft uses its instruments to probe beneath the obscuring cloud cover, studying Jupiter’s interior and auroras to learn more about the planet’s origins, structure, atmosphere, and magnetosphere.

Juno has been orbiting Jupiter for more than 2,505 Earth days and flown over 510 million miles (820 million kilometers). The spacecraft arrived at Jupiter on July 4, 2016. The first science flybyoccurred 53 days later, and the spacecraft continued with that orbital period until its flyby of Ganymede on June 7, 2021, which reduced its orbital period to 43 days. The Europa flyby on Sept. 29, 2022, reduced the orbital period to 38 days. After the next two Io flybys, on May 16 and July 31, Juno’s orbital period will remain fixed at 32 days.

“Io is only one of the celestial bodies which continue to come under Juno’s microscope during this extended mission,” said Juno’s acting project manager, Matthew Johnson of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “As well as continuously changing our orbit to allow new perspectives of Jupiter and flying low over the nightside of the planet, the spacecraft will also be threading the needle between some of Jupiter’s rings to learn more about their origin and composition.”

More About the Mission

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott J. Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 19.06.2023

.

Alien green flash: Lightning crackles in vortex near Jupiter's north pole (photo)

NASA's Juno probe captured the striking image.

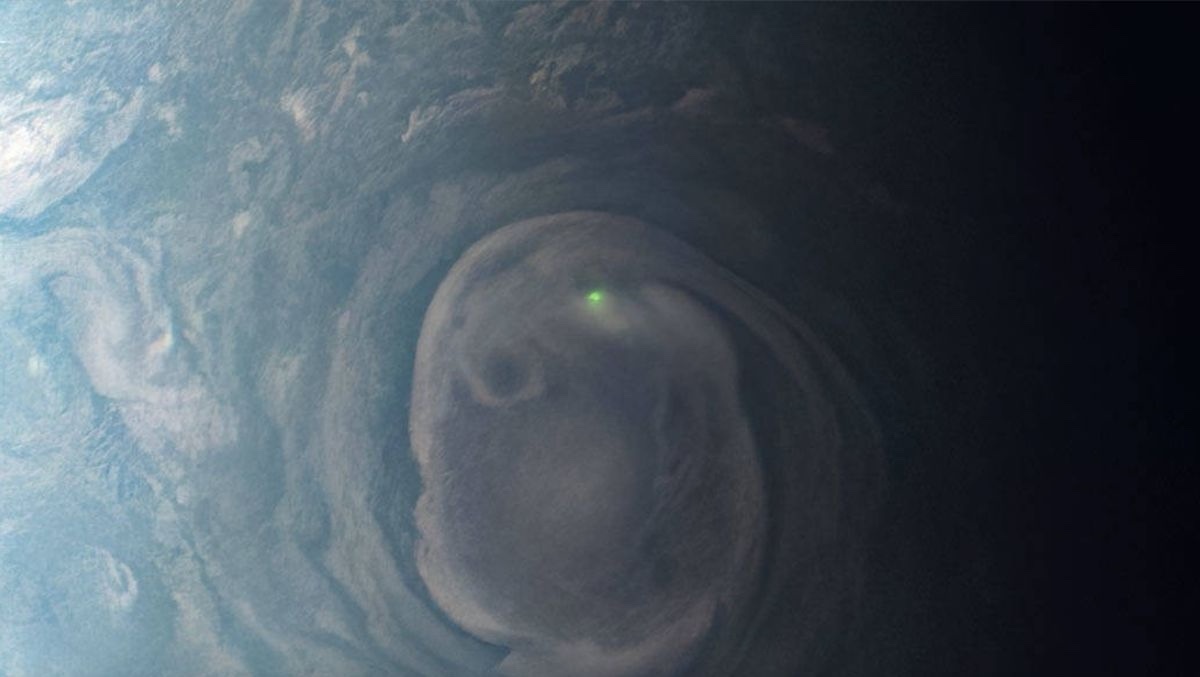

NASA's Juno spacecraft captured this view of a lightning strike in the clouds near Jupiter's north pole on Dec. 30, 2020.

NASA's Juno probe keeps giving us great looks at Jupiter's wild weather.

Juno has been looping around Jupiter on a highly elliptical path since July 2016, making detailed observations of the gas giant during close passes over its poles.

During its 31st such flyby, on Dec. 31, 2020, Juno captured a great shot of the greenish glow from a lightning strike inside a swirling vortex near Jupiter's north pole. The spacecraft was just 19,900 miles (32,000 kilometers) above the planet's cloud tops at the time, NASA wrote in a description of the image, which the agency released on Thursday (June 15).

Citizen scientist Kevin Gill processed the newly released image using raw data gathered by Juno's JunoCam instrument, NASA officials added. The Juno team welcomes such collaborations; you can try your image-processing hand at the JunoCam site.

This was not Juno's only brush with Jovian lightning — far from it, in fact. The spacecraft has observed many strikes in Jupiter's thick atmosphere, helping scientists determine that lightning on the gas giant is quite similar to the bolts we see here on Earth.

There are some key differences, however.

"On Earth, lightning bolts originate from water clouds, and happen most frequently near the equator, while on Jupiter lightning likely also occurs in clouds containing an ammonia-water solution, and can be seen most often near the poles," NASA officials wrote in the image description.

Juno has now performed 51 close passes of Jupiter, or "perijoves," as the mission team calls them. The next one will take place on June 23.

The first 35 perijoves were conducted during Juno's primary mission, which ended in July 2021. The probe's data have given scientists a much better understanding of Jupiter's structure, formation and evolution.

"Juno's many discoveries have changed our view of Jupiter's atmosphere and interior, revealing an atmospheric weather layer that extends far beyond its clouds and a deep interior with a diluted, or 'fuzzy,' heavy element core," NASA officials wrote in a mission description.

Juno is now flying on an extended mission that will last through at least September 2025, provided the spacecraft stays healthy in Jupiter's harsh radiation environment. During the extended mission, Juno is taking a wider look at the entire Jovian system, studying the planet, its rings and its many moons.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 30.06.2023

.

In Photos: NASA’s Juno At Jupiter Sends Back New Jaw-Dropping Images

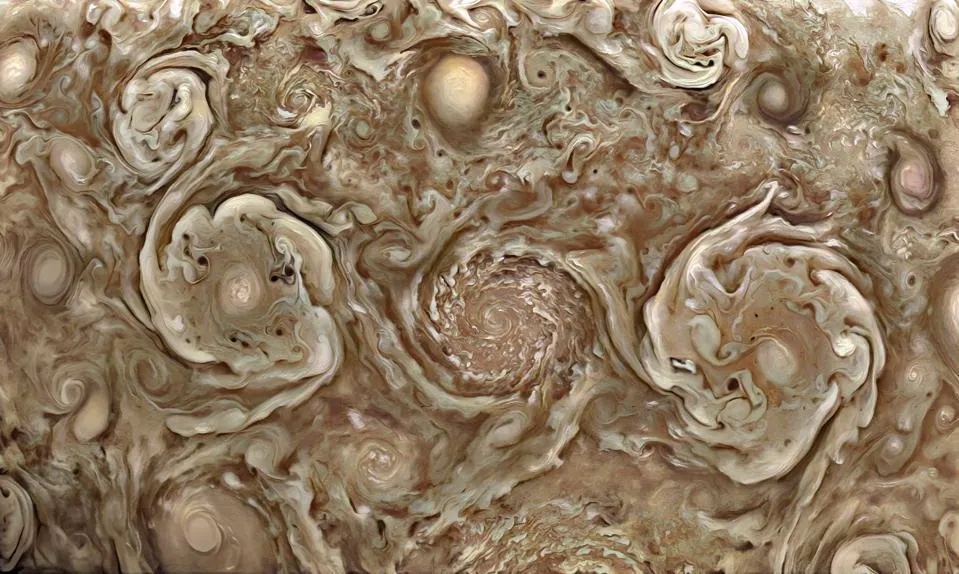

Just back from Jupiter are a batch of impressive new images of the giant planet’s cloud-tops in close-up.

They were taken last Friday, June 23, 2023 in raw format by the two-megapixel camera on-board NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which is spinning as it orbits the “King of Planets” 390 million miles/628 million kilometers away.

The furthest solar-powered spacecraft from Earth, Juno was on its 52nd perijove (close flyby).

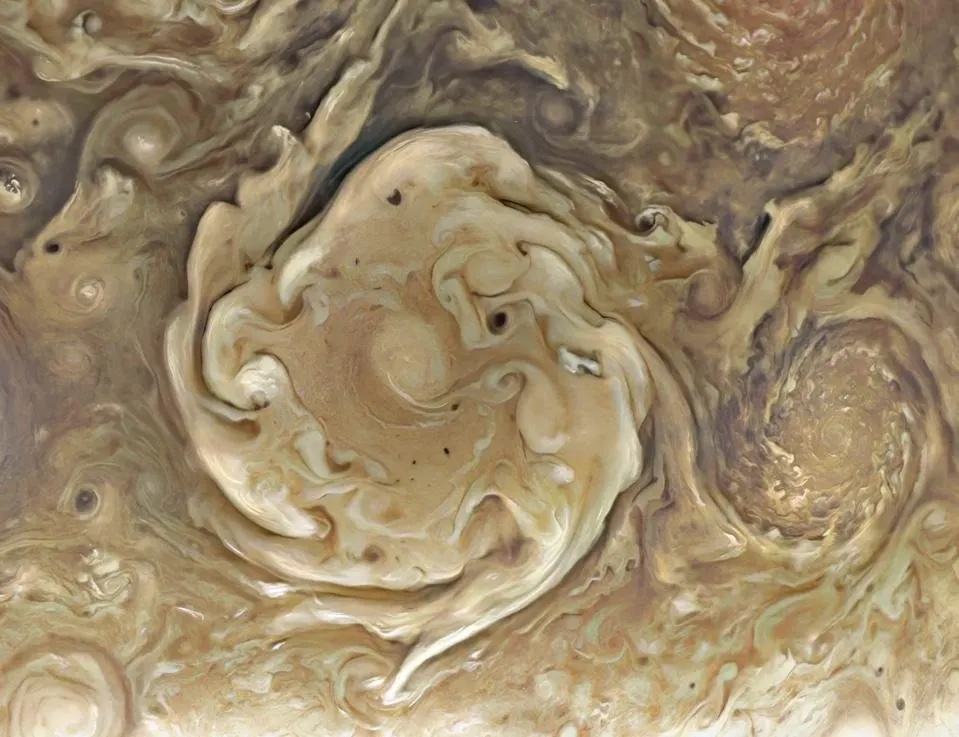

PJ52 - Three Northern Circumpolar Cyclones : Exaggerated and enhanced false color image of Jupiter's ... [+]

NASA/SWRI/MSSS/NAVANEETH KRISHNAN S © CC BY

The data takes about 34 light-minutes to travel across space thanks to NASA’s Deep Space Network—an array of three large radio telescopes in Goldstone in California, Madrid in Spain and Canberra in Australia.

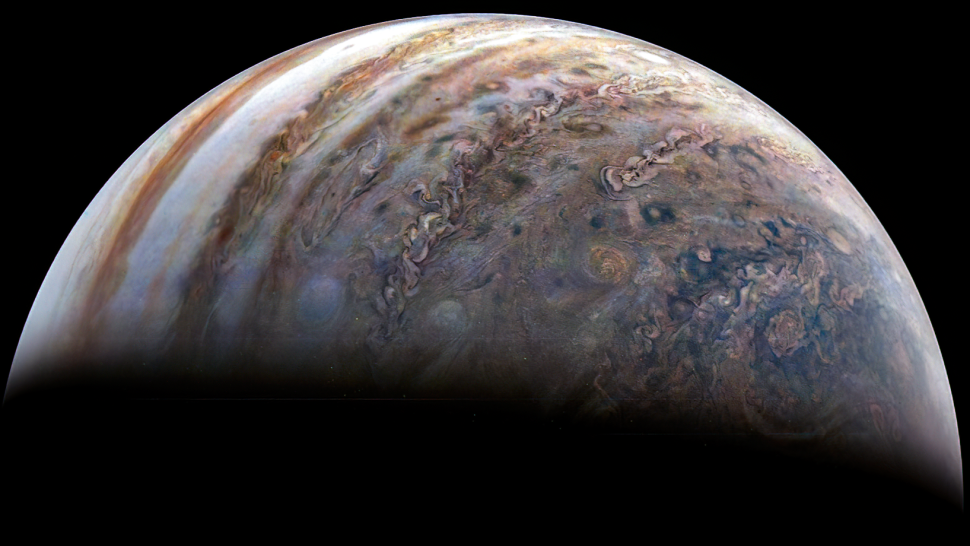

Jupiter as seen by NASA's Juno spacecraft during its perijove 52. Image processed by Kevin M Gill.

NASA/JPL-CALTECH/SWRI/MSSS/KEVIN M. GILL © CC BY

Built by Lockheed Martin and operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA’s $1.1 billion spacecraft successfully entered the orbit of Jupiter on July 4, 2016.

Since then it’s been on an elliptical orbit so it can cruise close to Jupiter’s cloud tops, though a major focus of its current extended mission are the large Galilean moons of Jupiter—Ganymede, Europa, Callisto and Io. It currently orbits Jupiter every 32 days.

Northern Circumpolar Cyclone in Enhanced False Color. Created from a raw image captured by JunoCam ... [+]

NASA/SWRI/MSSS/NAVANEETH KRISHNAN S © CC BY

So far it’s conducted close flybys of Ganymede in 2021 and Europa in 2022, the latter being a major target for astrobiologists searching for life elsewhere in the solar system.

During its last perijove on May 17, 2023, Juno imaged Jupiter’s moon Io from just 22,060 miles/35,500 kilometers above. The most volcanic object in the solar system, Io spews lava from volcanoes that cover its surface.

That energy comes from the fact that Io—which is slightly larger than Earth’s moon—is being constantly tugged by the gravity of Jupiter and also by the other moons.

Juno will flyby the volcanic moon of Io twice in its new extended mission, getting to within 900 miles/1,500 km of it on both December 30, 2023 and on February 3, 2024. However, Juno’s next perijove in July 2023 will also herald some more distant images of Io.

In April 2023 the European Space Agency’s new JUICE mission took-off to orbit Ganymede for nine months from 2034. It will become the first spacecraft ever to orbit a moon other than Earth’s.

By then, Juno will have been damaged by Jupiter’s radioactive environment and its engineers will have performed a “death dive” into the giant planet.

James Webb Space Telescope and Hubble will help NASA's Juno probe study Jupiter's volcanic moon Io

The telescopes will team up to assist NASA's Juno spacecraft the next time it flies by Io, our solar system's most volcanic body.

An illustration shows the Juno spacecraft flying past Io as Jupiter lurks in the background. (Image credit: NASA/ Robert Lea)

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Hubble Space Telescope are set to team up and observe the solar system's most volcanic body: A moon of Jupiter named Io.

The two space telescopes will remotely collect data about the intriguing world, then that information will be put to use by NASA's Juno spacecraft. More specifically, the data will help guide Juno during future flybys of Io, as the probe investigates how the highly volcanic moon may contribute to plasma present in the environment around Jupiter.

The investigation will conducted by the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), an organization that has been granted JWST and Hubble observing time by the Space Telescope Science Institute. The SwRI team will collect Io data with Hubbleduring 122 of the telescope's orbits around Earth, as well as supplement those findings with almost five hours of JWST observing time.

"The timing of this project is critical," Kurt Retherford, principal investigator of the campaign and SwRI researcher, said in a statement. "Over the next year, Juno will buzz past Io several times, offering rare opportunities to combine in-situ and remote observations of this complex system."

"We hope to gain new insights into Io’s dramatic volcanism, plasma-moon interactions and the neutral gas and plasma populations that propagate through Jupiter's vast magnetosphere and trigger intense Jovian auroral emissions," Retherford added.

NASA estimates that Io's surface is punctuated by hundreds of actively erupting volcanoes that can blast lava dozens of miles into the Jovian moon's thin, waterless atmosphere.

Io, which is around the size of Earth's moon and the innermost Galilean satelliteof Jupiter, is believed to be so extremely volcanic because the gravitational influences of its host planet generate tidal forces that squash and squeeze this moon. Other Jovian moons, including the rest of the Galilean satellites, have a similar effect on Io too, further exacerbating this gravitational storm.

These forces are so powerful, in fact, that they can provoke the surface of Io to rise and fall by as much as 330 feet (100 meters). And as you might expect, such extreme volcanism affects the entire Jovian system.

Io's extreme volcanism drives donut cloud around Jupiter

Particles escaping from Io's atmosphere, for instance, are believed to be a major source of material trapped in Jupiter's magnetic field. These escaping atmospheric gases are ionized, meaning they undergo a process in which extreme heat rips electrons from atoms to create a dynamic sea of charged particles.

"Most of these materials don’t actually escape straight out of the volcanoes but rather are associated with the sublimation of sulfur dioxide frost from Io's dayside surface," Katherine de Kleer, project co-investigator and scientist at Caltech, said in the statement. "The interaction between Io’s atmosphere and the surrounding plasma provides the escape mechanism for gases released from the moon's frozen surface."

This forms a doughnut-shaped cloud of charged particles, called the Io Plasma Torus (IPT), surrounding Jupiter. When electrons collide with ions in the IPT, they create ultraviolet radiation that can be detected by telescopes here on Earth and in space.

Continued investigation is needed to fully understand the IPT, however, because it is difficult to assess how strong its connection to Io's volcanism actually is. It's also an open question as to what effects Io has on other bodies in the Jovian system, such as those other large Galilean moons.

"For example, how much sulfur is transported from Io to Europa's surface? How do auroral features on Io compare with aurora on Earth — the northern lights — and Jupiter?" Fran Bagenal, project co-principal investigator and researcher at the University of Colorado at Boulder, said in the statement.

The team believes the key to better understanding these connections is by investigating the Jovian system as a whole rather than in pieces. And that requires more data than even Juno, as impressive as it is, can provide.

"Hey Hubble ... watch this!"

Juno has been investigating the Jovian system and its environment since July 4, 2016, when it arrived in the vicinity of the gas giant and its moons after a 1.7 billion-mile journey from Earth. This was a journey that took five years to complete.

Since then, the spacecraft has completed several flybys of both Jupiter and its large moons, notably Europa. It last flew past Io on July 30, coming within around 13,700 miles (22,000 kilometers) of the fiery moon while collecting data about its atmosphere and magnetic field. Juno will get particularly close to Io again on Dec. 30 of this year then again on Feb. 1, 2024.

On Sept. 20, however, Juno will make a more distant pass of Io that will be of particular interest to the SwRI team. This flyby of Io will be timed such that it can be observed by Hubble and the JWST simultaneously.

That means the two telescopes will get the chance to team up and observe what Juno sees, but at a distance, giving scientists the holistic view of the Jovian system they're after.

"The chance for a holistic approach to Io investigations has not been available since a series of Galileo spacecraft flybys in 1999 to 2000 were supported by Hubble with a prolific 30-orbit campaign," Retherford concluded. "The combination of Juno’s intensive in-situ measurements with our remote-sensing observations will undoubtedly advance our understanding of Io's role in driving coupled phenomena in the Jupiter system."

Even though future missions to Jupiter and its moons are in the cards, with the Europa Clipper and Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) set to arrive at the Jovian system between 2029 and 2031, neither will fly by Io.

That means, according to the SwRI, another chance to make these kinds of observations won't arise until at least the 2030s.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 17.09.2023

.

NASA's Juno mission captures stunning view of Jupiter with its volcanic moon, Io (photo)

Citizen scientist Alain Mirón Velázquez made a few photo adjustments to create the dramatic visual.

NASA’s Juno spacecraft snapped a new view of Jupiter and its volcanic moon, Io, on July 30 ahead of a scheduled close flyby of the gas giant. (Image credit: ASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Alain Mirón Velázquez © CC BY)

NASA's Juno mission has captured a stunning new portrait of Jupiter with its volcanic moon, Io.

Juno snapped this new view on July 30 as it passed by Io ahead of its 53rd close flyby of Jupiter the following day. The photo captures Jupiter in the foreground with an up-close view of the gas giant’s colorful cloud bands and swirling spots. The sliver of Io captured in the background showcases the moon’s dark, molten-red surface.

Using raw data from the JunoCam instrument, citizen scientist Alain Mirón Velázquez created this dramatic view by enhancing the contrast, color and sharpness of the celestial bodies. The spacecraft was about 32,170 miles (about 51,770 kilometers) from Io, and about 245,000 miles (about 395,000 kilometers) above Jupiter’s cloud tops at the time the photo was taken, according to a statement from NASA.

Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system, has a total of 92 moons. Io, Jupiter’s fifth moon, is only slightly larger than Earth’s moon and the fourth-largest moon in the solar system. It is Jupiter's third-largest and the innermost Galilean satellite — which refers to the four Jupiter moons that were the first celestial objects to be discovered orbiting an object other than the sun by Galileo Galilei in 1610.

Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system, home to hundreds of volcanoes that regularly erupt with molten lava and spew sulfurous gas plumes hundreds of miles upward into the atmosphere. Recent close flybys of Io have allowed scientists to study the volcanic moon and its tortured surface in even greater detail.

"Juno has provided scientists with the closest looks at Io since 2007, and the spacecraft will gather additional images and data from its suite of scientific instruments during even closer passes in late 2023 and early 2024," NASA officials said in the statement.

The images collected by Juno are available online to the public. Access to the spacecraft’s raw data has allowed citizen scientists to help make thousands of important scientific discoveries since Juno reached Jupiter in 2016.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 21.10.2023

.

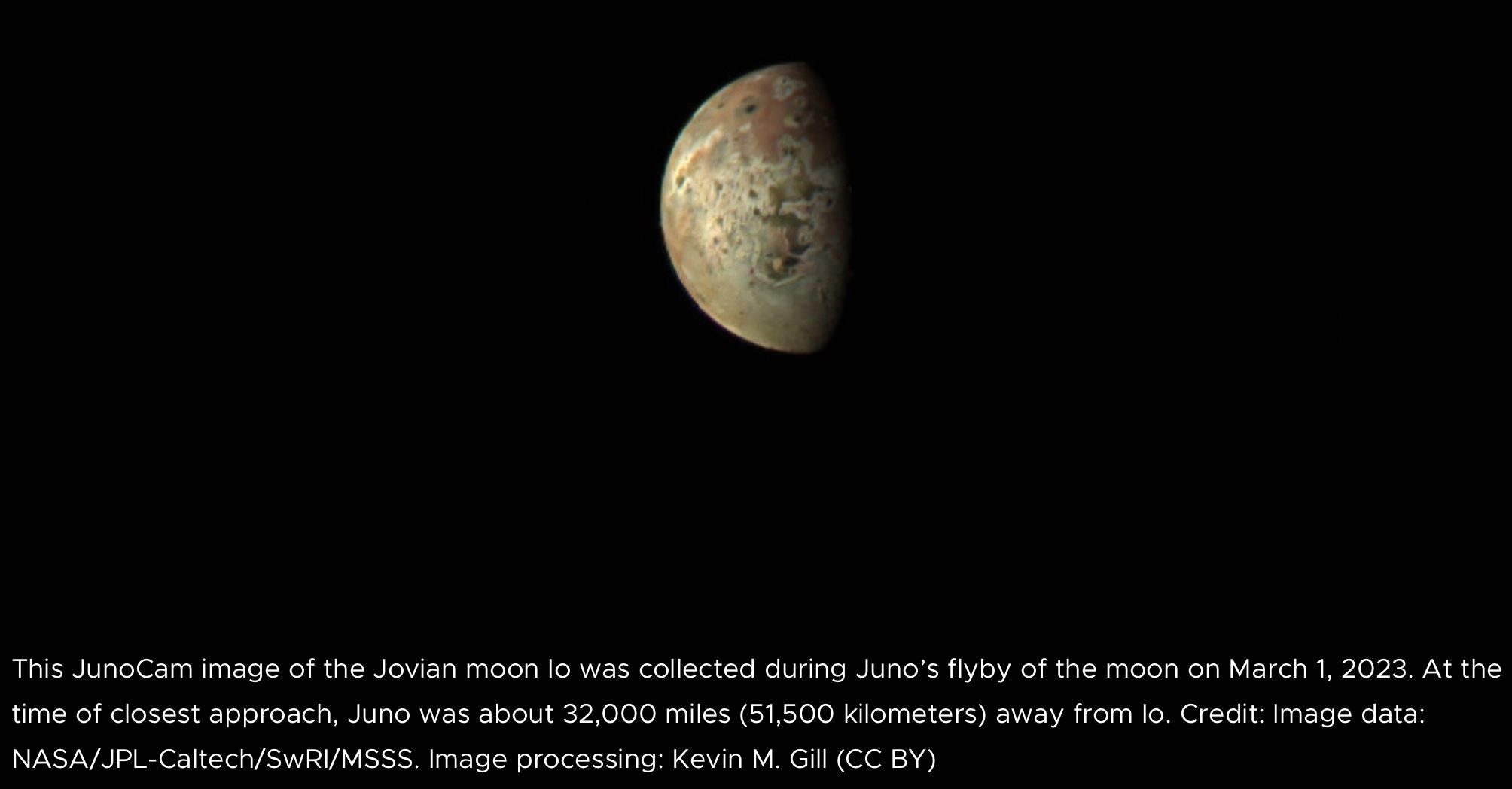

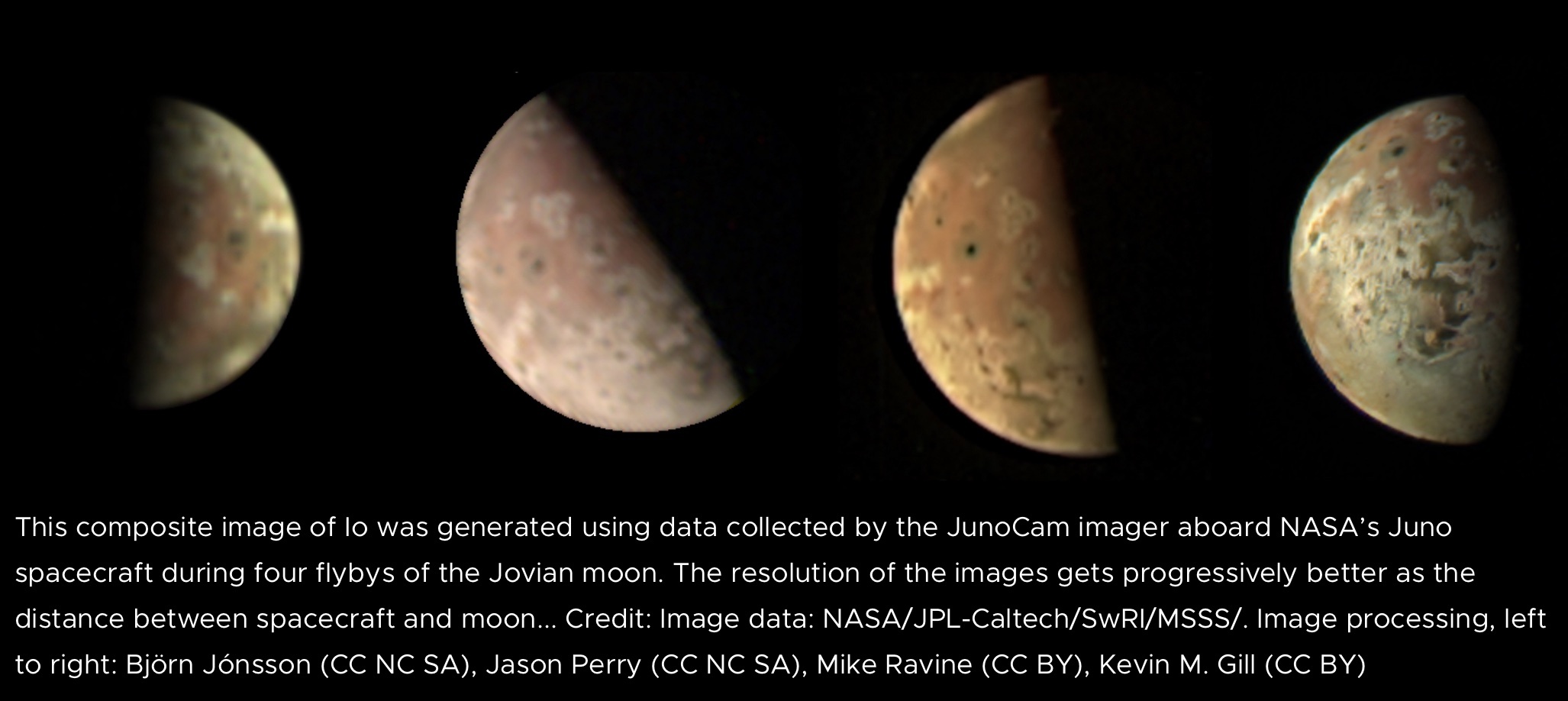

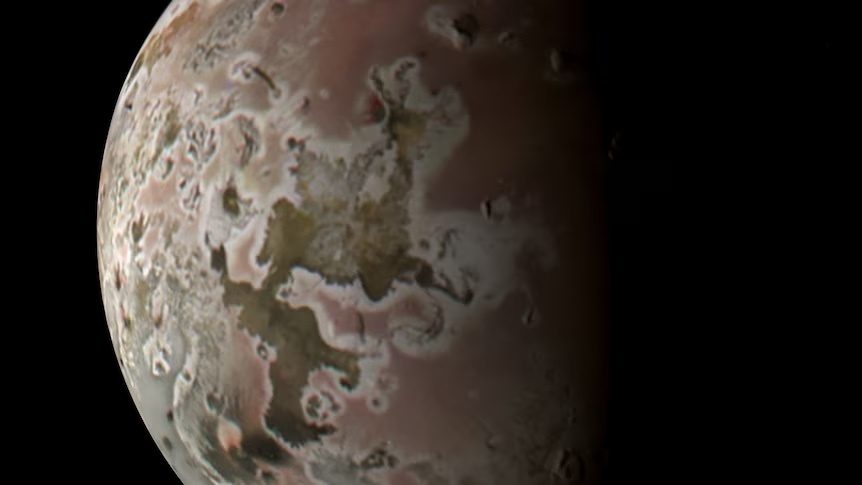

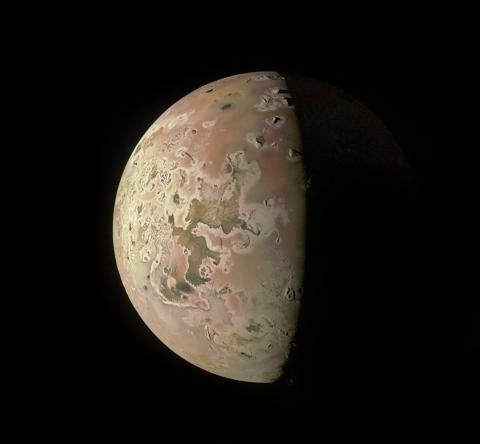

NASA shares never-before-seen images of Jupiter's lava-covered moon, Io

Jupiter's moon Io, captured by NASA's Juno probe.(Supplied: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill)

NASA has released detailed images of Io, one of about 90 moons revolving around Jupiter, using the space agency's Juno probe.

The spacecraft captured the images of the moon on a recent flyby. The images were created by citizen scientists who processed them using the raw data captured by the Juno probe.

What is Io?

Io is the most volcanically active world in the Solar System, according to NASA. Hundreds of volcanoes cover its mottled surface, some erupting lava fountains that reach kilometres high.

So powerful are these volcanic blasts that they are, at times, able to be observed from Earth using large telescopes.

Io even has lakes of molten silicate lava on its surface.

Io is covered with hundreds of active volcanoes.(Supplied: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Ted Stryk)

The new images from the Juno probe reveal the moon's swirling surface, highlighted with large molten-red patches.

Only slightly larger than the Earth's Moon, Io is stuck in a tug-of-war between Jupiter's massive gravity as well as orbital pulls from two of Jupiter's other moons — Europa and Ganymede.

The result is that Io is frequently stretched and squeezed by the pull, actions NASA says are linked to the torrents of lava seen erupting from its multiple volcanoes.

Juno will return to observe more of this volatile moon in December when the probe will buzz just 1,500 kilometres above Io's surface.

Quelle: ABC News

----

Update: 27.10.2023

.

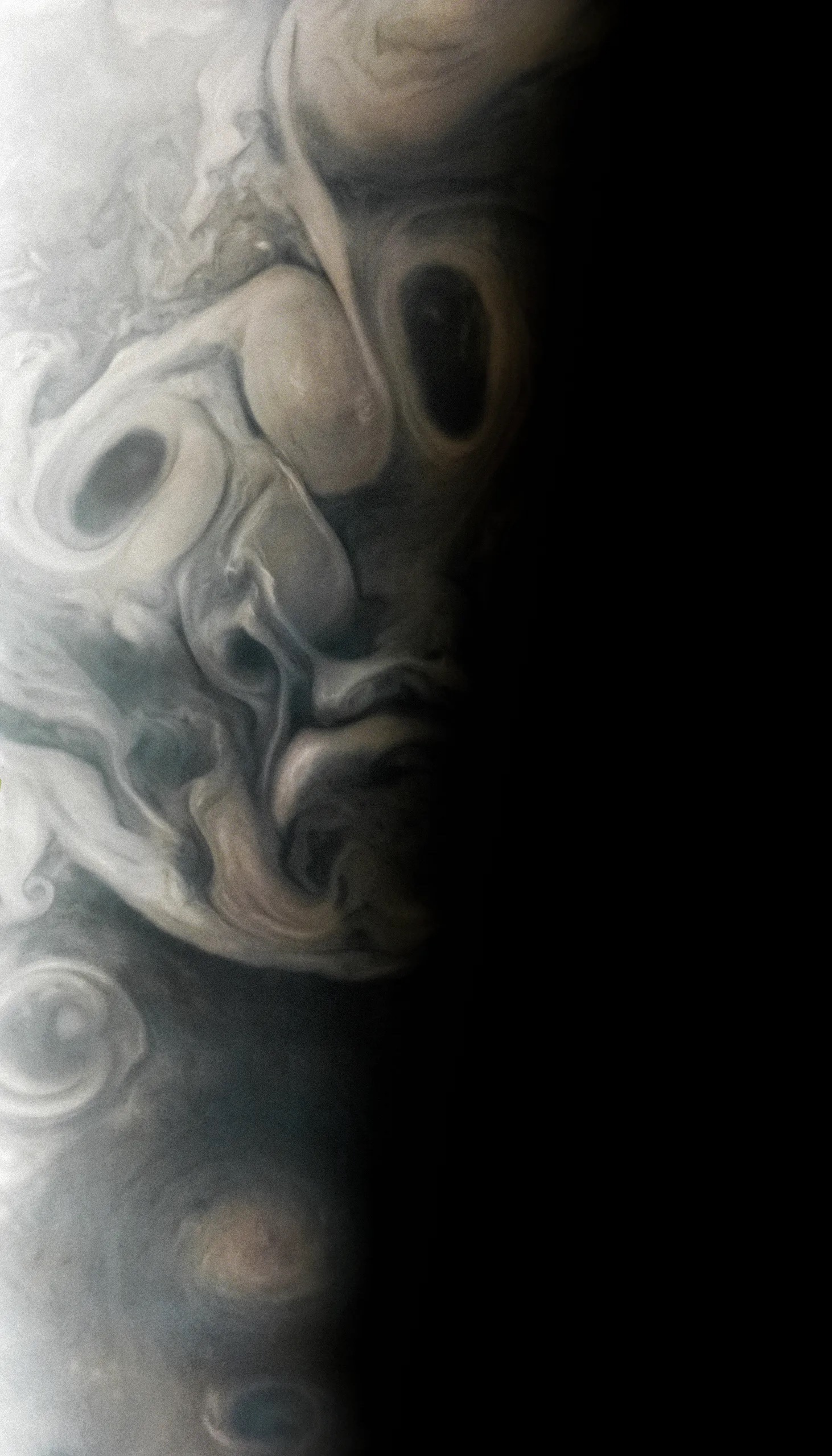

Just in Time for Halloween, NASA’s Juno Mission Spots Eerie “Face” on Jupiter

On Sept. 7, 2023, during its 54th close flyby of Jupiter, NASA’s Juno mission captured this view of an area in the giant planet’s far northern regions called Jet N7. The image shows turbulent clouds and storms along Jupiter’s terminator, the dividing line between the day and night sides of the planet. The low angle of sunlight highlights the complex topography of features in this region, which scientists have studied to better understand the processes playing out in Jupiter’s atmosphere.

As often occurs in views from Juno, Jupiter’s clouds in this picture lend themselves to pareidolia, the effect that causes observers to perceive faces or other patterns in largely random patterns.

Citizen scientist Vladimir Tarasov made this image using raw data from the JunoCam instrument. At the time the raw image was taken, the Juno spacecraft was about 4,800 miles (about 7,700 kilometers) above Jupiter’s cloud tops, at a latitude of about 69 degrees north.

Quelle: NASA