Georg von Tiesenhausen helped NASA get humans on the moon, but before he was brought to the US through Operation Paperclip, he was designing missiles for the Nazis.

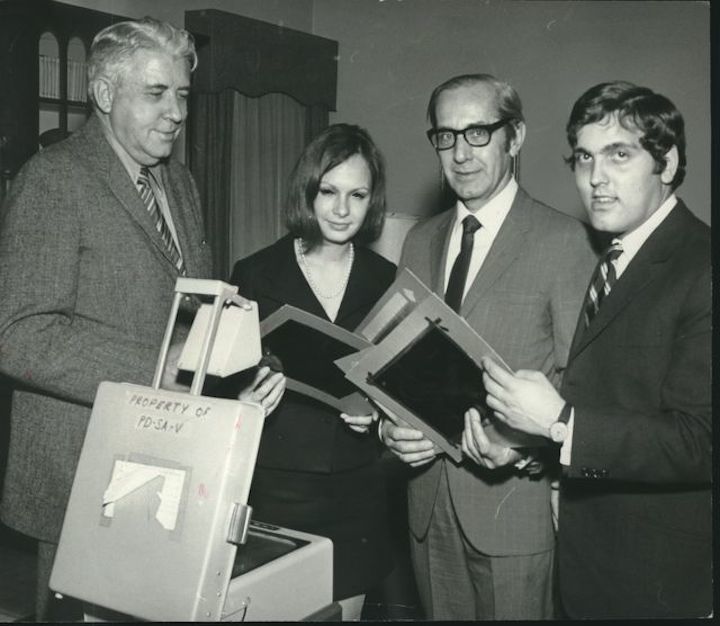

Georg von Tiesenhausen. Image: YouTube

On Tuesday, the Associated Press reported that the rocket scientist Georg von Tiesenhausen had died at his Alabama home at the age of 104. Von Tiesenhausen was the last living NASA scientist to have worked on Nazi rockets after being brought to the US as part of the secretive Operation Paperclip.

Von Tiesenhausen, known as “Von T” by those close to him, dedicated his life to rocket science. When Niel Armstrong presented him with the US Space and Rocket Center’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011, he described von Tiesenhausen as “one of those rare individuals who has a natural ability to inform and inspire, to educate and motivate, and most remarkably, to endure.” During his decades-long career with NASA, von Tiesenhausen worked on the platform that moved the massive Saturn V rocket used to carry the first men to the moon to its launch pad. However he is perhaps best known for his conceptual design of the lunar rover that was used on the last three crewed Apollo missions to the moon.

Before he worked at NASA, however, von Tiesenhausen cut his teeth as a rocket scientist at Peenemünde, the Nazi’s premiere weapon research center.

“To enter the area of Peenemünde was one of the greatest surprises of my life,” von Tiesenhausen said in a television interview from the 80s. “Since the age of 14 I knew exactly what I wanted to do with the rest of my life: To be involved in rocketry and spaceflight.”

The research center was best known as the stomping grounds of the pioneering rocket scientist Werner von Braun—who was Peenemünde’s director— and von Tiesenhausen spent his days at the research center as a section officer working on the Nazi’s V-2 rocket. This rocket is infamous for being the world’s first long range, guided ballistic missile.

Unlike von Braun, who joined the Nazi party before World War II and served as a member of the SS, von Tiesenhausen’s joined von Braun’s Peenemünde team in 1943 fresh out of Hamburg University where he had studied engineering after a brief stint in the army. He had been recruited as part of a wider effort in Germany that year to beef up the Nazi regime’s science and engineering corps, which included recalling thousands of scientists from the front lines.

Von Tiesenhausen initially focused on designing test stands for V-2 engines, but by the end of the war he had been tasked with working on a top secret project code-named Test Stand 12. This project aimed to develop a fleet of mini-submarines that would be capable of launching V-2 rockets at distant targets. "We wanted to give the V-2 a long range, say to launch it to Manhattan,” he recalled of his work on the project at Peenemünde. “Not just one, but as many as possible.”

Fortunately, the war ended before the project ever made it beyond a prototype phase.

Following the war, the United States began bringing hundreds of German scientists and engineers to America as part of Operation Paperclip. Many of the Germans were enlisted to help work on rockets for NASA and the military, including von Braun, who arrived in the US in 1945 and was stationed at an Army facility in Huntsville, Alabama starting in 1950. Three years later, von Tiesenhusen was also relocated to the Huntsville facility where he would initially work on Redstone rockets for the military.

“After the war, I was fortunate to be invited to the United States to work on weapons systems, ironically,” von Tiesenhausen said, noting the similarities between the Nazi’s rocket programs and the United States’ rocket programs. “The early days of Peenemünde laid the ground stone for what we were doing here. Our first missile here, the Redstone, was just a glorified V-2. The people at Peenemünde were really the originators of most of the concepts we deal with today.”

After a few years working on missiles for the military, von Tiesenhausen was transferred to NASA’s Marshall Spaceflight Center to help with the Apollo program. This is where he would spend the next thirty years working on cutting edge space exploration concepts.

“We were the only group at that time that knew how to build long range rockets,” von Tiesenhausen said, referring to von Braun’s team in a wide-ranging interview from 1988. Despite their expertise, von Tiesenhausen noted that some Americans felt uneasy about the Germans working for the US after the war, even if the relationship between von Braun’s team and their American military colleagues was mostly cordial.

“There were certain ethnic groups—Jewish groups, mainly—in the United States who were against us in principle,” von Tiesenhausen said. “The ethnic prejudices operated the entire time we had the von Braun team. The prejudice was not across the board, it was just certain individuals. My colleagues and I had excellent relationships to a number of Jews, which were in different positions at headquarters.”

Despite these underlying tensions, von Tiesenhausen soon became an “in house brainstormer” for NASA who was responsible for coming up with new ideas. In 1959, he came up with the idea for a lunar rover, which von Tiesenhausen described as “a disaster,” based on senior officials’ reaction to the idea. Yet 12 years later, a rover almost identical to the one designed by von T would carry astronauts across the lunar surface.

Von Tiesenhausen worked on various Apollo-related projects during the 60s and 70s, as well as helping NASA develop its robotic space exploration program. Yet when he was approached and asked to support President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, commonly known as Star Wars, he refused. “I had a principle,” von Tiesenhausen said. “I worked on weapons systems long enough in my life and I didn’t want anything to do with that, especially as a NASA employee.”

By the late 80s, von Tiesenhausen had retired from active technical development at NASA and spent most of his later working years helping with space educational programs, such as giving presentations to kids at space camp.

It’s a rather soft landing for a man who once developed submarine missiles meant to destroy New York City, even if von Tiesenhausen’s wartime activities seemed to cultivate within him a desire to see peaceful space exploration replace space warfare. At a time when the Trump administration is ramping up calls for a space force in the military, von Tiesenhausen’s vision seems like impossible idealism, but at one point, so did his ideas for a lunar rover.

Quelle: Motherboard