.

On his third orbit of the Earth, Ed White opened the hatch and floated out into thin air.

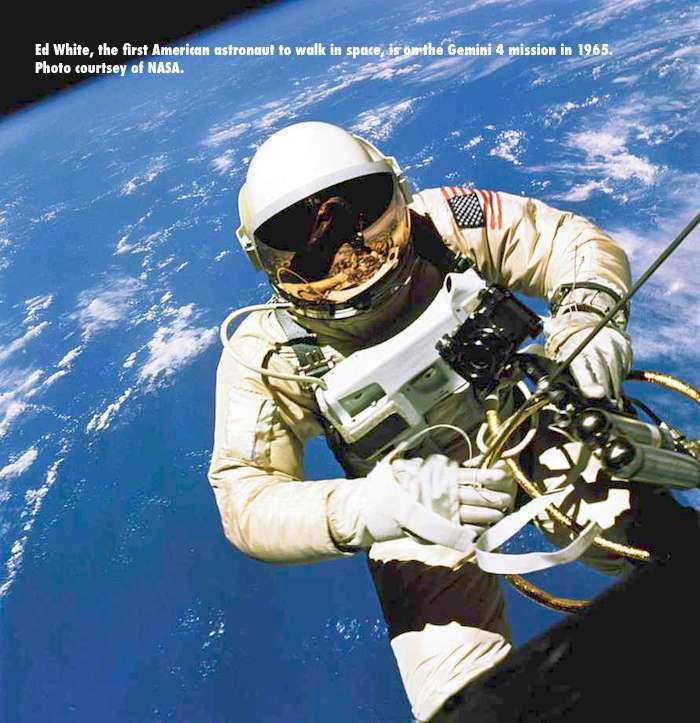

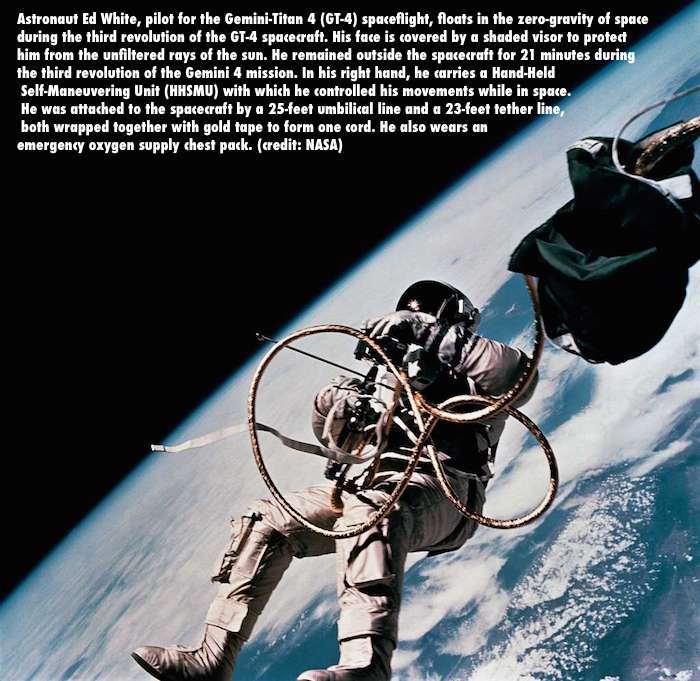

He remained aloft, tethered to his spacecraft by a golden umbilical cord, as the span of the United States passed, west to east, before him.

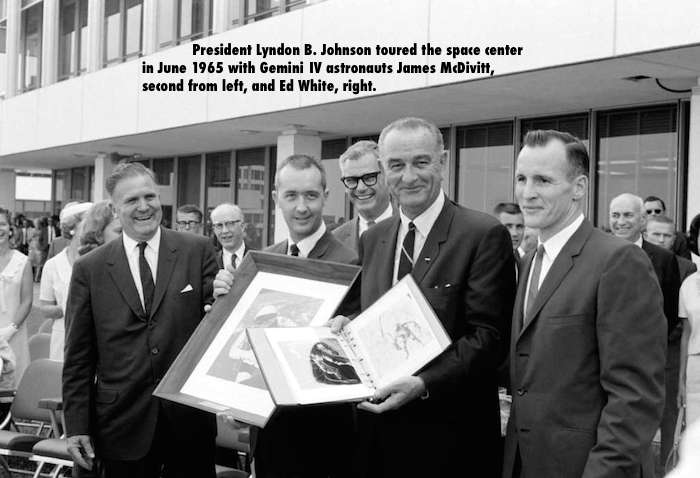

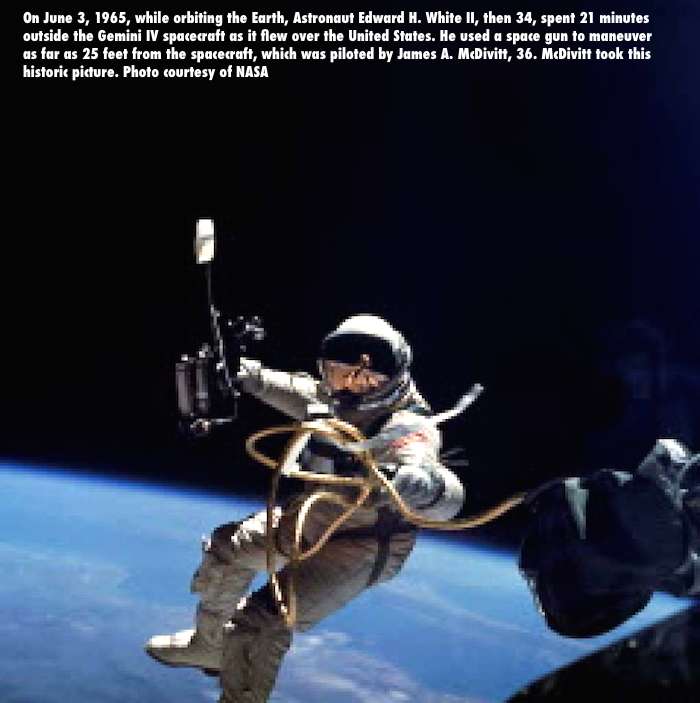

It was June 3, 1965 - a halfway point in the decade in which President John F. Kennedy promised to put a man on the moon - when White became the first American to "walk" in space. Houston-directed operations and an international audience watched the launch on satellite television and heard the spacewalk via radio.

Amid the feverish space race with the Soviet Union, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration wanted its astronauts to attempt the first extravehicular activity, known as EVA, a vital threshold in preparing for a lunar landing and exploration. The Soviet space program beat them to it by three months.

Still, the two-man Gemini IV launch marked several historic firsts. White was first to use a handheld jet gun to maneuver in space. He and Commander James A. McDivitt were the first Americans to undertake a multiple-day mission. And most notably for Earth-bound participants in the space program, Gemini IV was the inaugural flight overseen by Houston's cutting-edge Mission Operations Control Room, which cemented the city's name in the global vernacular as the center of human spaceflight.

The Gemini IV crew knew the voyage was a huge turning point for Houston. It was so monumental that the Bayou City's geography came up during the 20-plus breathtaking minutes one astronaut was in and the other out of the capsule.

"Ed," McDivitt said as White drifted past outside the spacecraft, "I don't know exactly where we are, but it looks like we're about over Texas. As a matter of fact, you know? That area looks like Houston down below us."

Astronauts have made hundreds of spacewalks since that day, most recently involving the International Space Station. The tools and steering methods have revolved from rudimentary to precise, and the walks have become almost routine. And while spacewalks are necessary for astronauts to move from one vehicle to another, they primarily are necessary for installing and repairing equipment.

The first American spacewalk had been a long time coming.

The Soviets were already ahead in the space program by then, and Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov performed the world's first spacewalk on March 18, 1965. It was a feat motivated more by political brinksmanship than science, according to Walt Cunningham, an Apollo generation NASA astronaut who lives in Houston and has long been friends with Leonov.

Americans didn't know until years later that the mission had been perilous for Leonov, who soared outside his spaceship for 10 minutes on a 10-foot extension line. Leonov's visor fogged up and he became dangerously overheated as he tried to work his way, blindly, into the inflatable airlock.

The Soviets wanted to be first and were willing to take chances at the height of the space race to reach their goals, said Michael Neufeld, the senior curator of space history at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Completing the first spacewalk was par for the course.

By the 1960s, NASA engineers and astronauts began planning and training for a practice spacewalk. The original goal was for White to open the hatch and simply stand up in his seat, but a week after Leonov's spacewalk, a group of NASA engineers gathered in Houston to begin planning for White to venture outside the cabin, said Joe McMann, one of the engineers at the secret meeting.

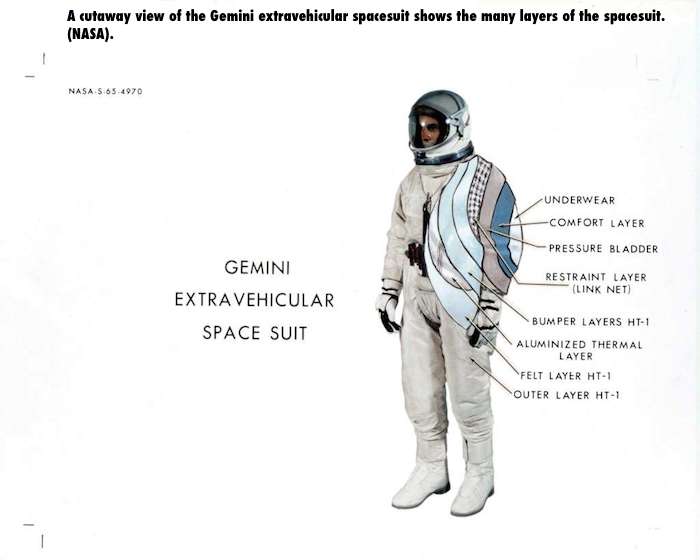

The engineers rigged up a modified spacesuit with an insulated cover layer and a gold-coated visor to protect against infrared radiation. The 25-foot umbilical line contained a tube that delivered oxygen and ventilation to the spacewalker, with wires to monitor his vital signs and transmit communication between him and the pilot. He would move through space using a nitrogen gas propulsion gun that resembled handlebars. He'd have a camera to shoot what turned out to be the clearest images ever taken from space.

Edward Higgins White II was selected to make the walk.

White grew up in San Antonio, the son of a retired Air Force general. He was a star hurdler at West Point who studied aeronautical engineering and flew in the Air Force. He was selected to be an astronaut in 1962 along with Neil Armstrong.

Gemini IV was his first and only flight. He died with two others on Jan. 27, 1967, in a cockpit fire during a test for the Apollo I flight.

During the Gemini IV voyage, McDivitt, also an Air Force pilot and aeronautical engineer, was at the helm for the spacewalk and other projects.

Over three hours into the flight, White put on and pressurized his EVA suit and depressurized the cabin. Over Hawaii, he cranked open the hatch and stood in his seat. McDivitt then told him, "We just had word from Houston. We're ready to have you get out whenever you're ready."

White untangled his feet and separated from the spacecraft. Then he tested the propulsion gun in bursts, which sent him spinning at odd angles. He saluted his commander.

"It's just tremendous," White said. "Looks like we're coming up on the coast of California."

White was hovering above Florida when Houston CAPCOM - capsule communications - ordered him back to the cabin. White was reluctant, lamenting half-jokingly, "It's the saddest moment of my life." He struggled to get back into his seat, to movein his spacesuit, to yank the stiff tubing into the spacecraft and close the hatch, as night fell over the Atlantic.

The spacewalk was a success. And though the mission's attempt to rendezvous with its second-stage rocket failed, the crew completed nearly a dozen experiments during 62 orbits. The capsule splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean four days after launch, on June 7.

-

Quelle: HoustonChronicle