2.08.2022

Scientists have supercharged one of Earth's most powerful telescopes with new technology that will reveal how our galaxy formed in unprecedented detail.

The William Herschel Telescope (WHT) in La Palma, Spain will be able to survey 1,000 stars per hour until it has catalogued a total of five million.

A super-fast mapping device linked up to WHT will analyse the make-up of each star and the speed at which it travels.

It will show how our Milky Way galaxy was built up over billions of years.

Prof Gavin Dalton of Oxford University has spent more than a decade developing the instrument, known as 'Weave'.

He told me that he was "beyond excited" that it is ready to go.

"It's a fantastic achievement from a lot of people to make this happen and it's great to have it working," he said. "The next step is the new adventure, it's brilliant!"

BBC Science Correspondent Pallab Ghosh meets the scientists on a mission to discover where the stars we see in the night sky came from

Weave has been installed on the WHT, which sits high on a mountain top on the Spanish Canary Island of La Palma. The name stands for WHT Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer - and that's exactly what it does.

It has 80,000 separate parts and is a miracle of engineering.

For each patch of sky the WHT is pointed at, astronomers identify the positions of a thousand stars. Weave's nimble robotic fingers then carefully place a fibre-optic - a light-transmitting tube - precisely on each location on a plate, pointing towards its corresponding star.

These fibres are in effect tiny telescopes. Each one captures light from a single star and channels it to another instrument. This then splits it into a rainbow spectrum, which contains the secrets of the star's origin and history.

All this is completed in just one hour. While this is going on, fibre optics for the next thousand stars are positioned on the reverse side of the plate, which flips over to analyse the next set of targets once the previous survey has been completed.

Our galaxy is a dense spiral swirl of up to 400 billion stars. But it started out as a relatively small collection of stars.

It grew from successive mergers with other small galaxies over billions of years. As well as the addition of stars from the new galaxies joining ours, each merger stirs things up enough to lead to brand new star formation.

Weave is able to calculate the speed, direction, age and composition of each star it observes, essentially creating a motion picture of stars moving in the Milky Way. According to Prof Dalton, by extrapolating backwards, it will be possible to reconstruct the entire formation of the Milky Way in detail never seen before.

"We'll be able to trace the galaxies that have been absorbed as the Milky Way has been built up over cosmic time - and see how each absorption triggers new star formation," he said.

Dr Marc Balcells, who is in overall charge of the WHT told BBC News that he believed that Weave would lead to a big shift in our understanding of how galaxies are made.

''We have been hearing for decades that we are in a golden era of astronomy - but what the future awaits is a lot more important.

"Weave is going to be answering questions that astronomers have been trying to answer for decades such as how many pieces come together to make a big galaxy and how many galaxies were united to make the Milky Way."

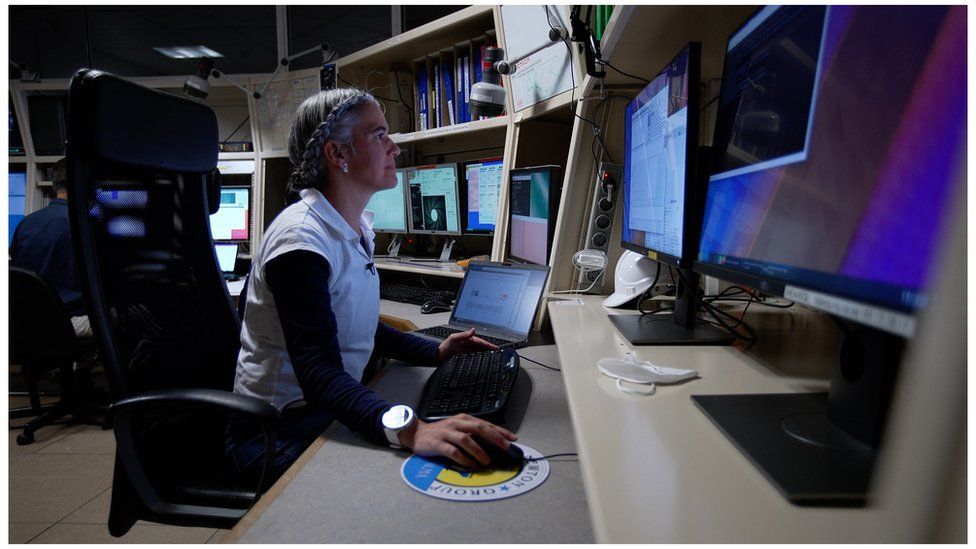

Dr Cecilia Farina, an instrumentation specialist on the project, said she believed that Weave would make astronomical history.

"There are an enormous amount of things that we are going to discover that we had not expected to find," she said. "Because the Universe is full of surprises."

Quelle: BBC News