21.06.2022

BepiColombo lines up for second Mercury flyby

The ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission is gearing up for its second close flyby of Mercury on 23 June. ESA’s spacecraft operation team is guiding BepiColombo through six gravity assists of the planet before entering orbit around it in 2025.

Like its first encounter last year, this week’s flyby will also bring the spacecraft to within about 200 km altitude above the planet’s surface. Closest approach is anticipated at 09:44 UT (11:44 CEST).

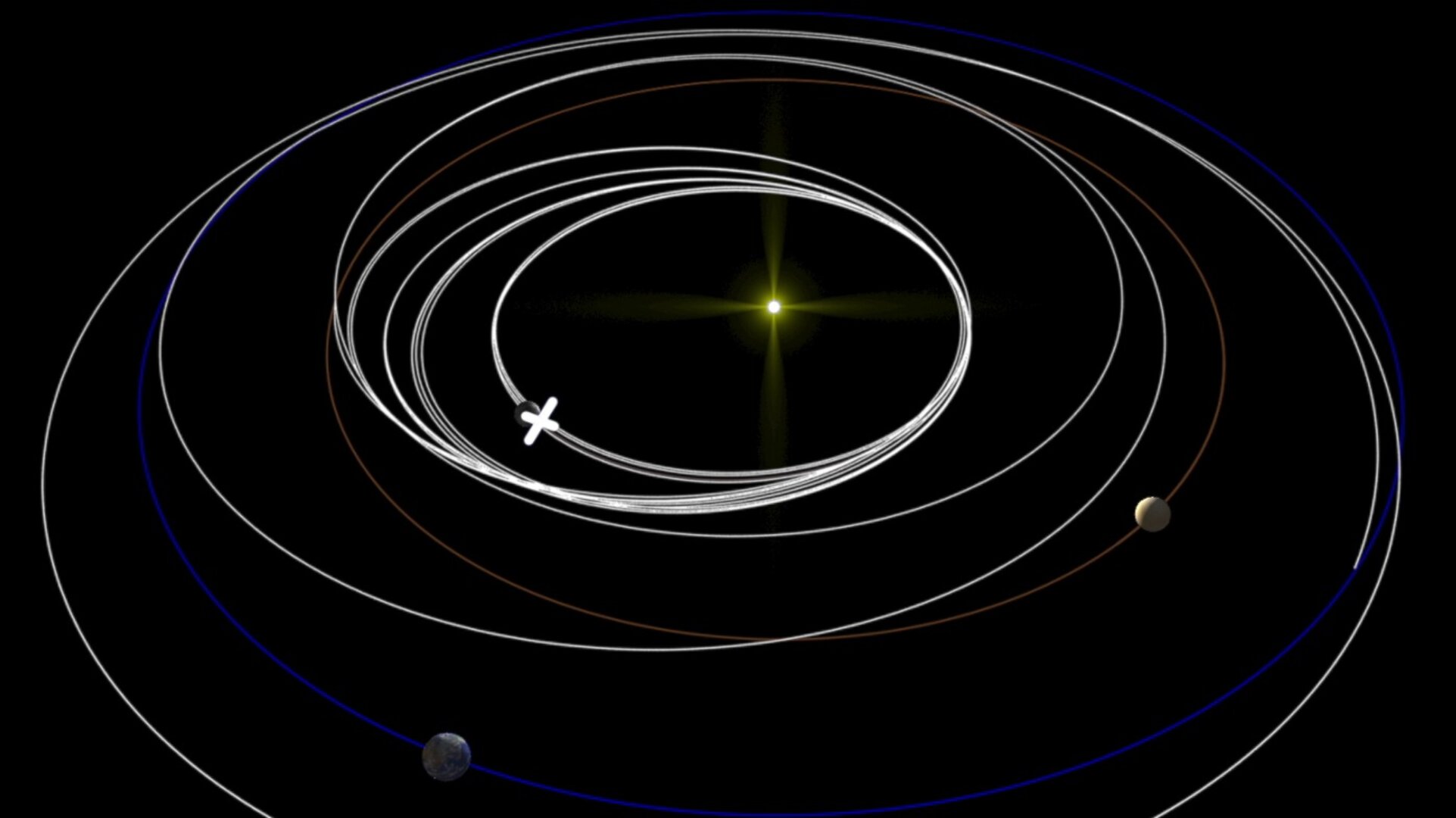

The primary purpose of the flyby is to use the planet’s gravity to fine-tune BepiColombo’s trajectory. Having been launched into space on an Ariane 5 from Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou in October 2018, BepiColombo is making use of nine planetary flybys: one at Earth, two at Venus, and six at Mercury, together with the spacecraft’s solar electric propulsion system, to help steer into Mercury orbit against the enormous gravitational pull of our Sun.

Even though BepiColombo is in ‘stacked’ cruise configuration for these brief flybys, meaning many instruments cannot yet be fully operated, it can still grab an incredible taste of Mercury science to boost our understanding and knowledge of the Solar System’s innermost planet. A sequence of snapshots will be taken by BepiColombo’s three monitoring cameras showing the planet’s surface, while a number of the magnetic, plasma and particle monitoring instruments will sample the environment from both near and far from the planet in the hours around close approach.

“Even during fleeting flybys these science ‘grabs’ are extremely valuable,” says Johannes Benkhoff, ESA’s BepiColombo project scientist. “We get to fly our world-class science laboratory through diverse and unexplored parts of Mercury’s environment that we won’t have access to once in orbit, while also getting a head start on preparations to make sure we will transition into the main science mission as quickly and smoothly as possible.”

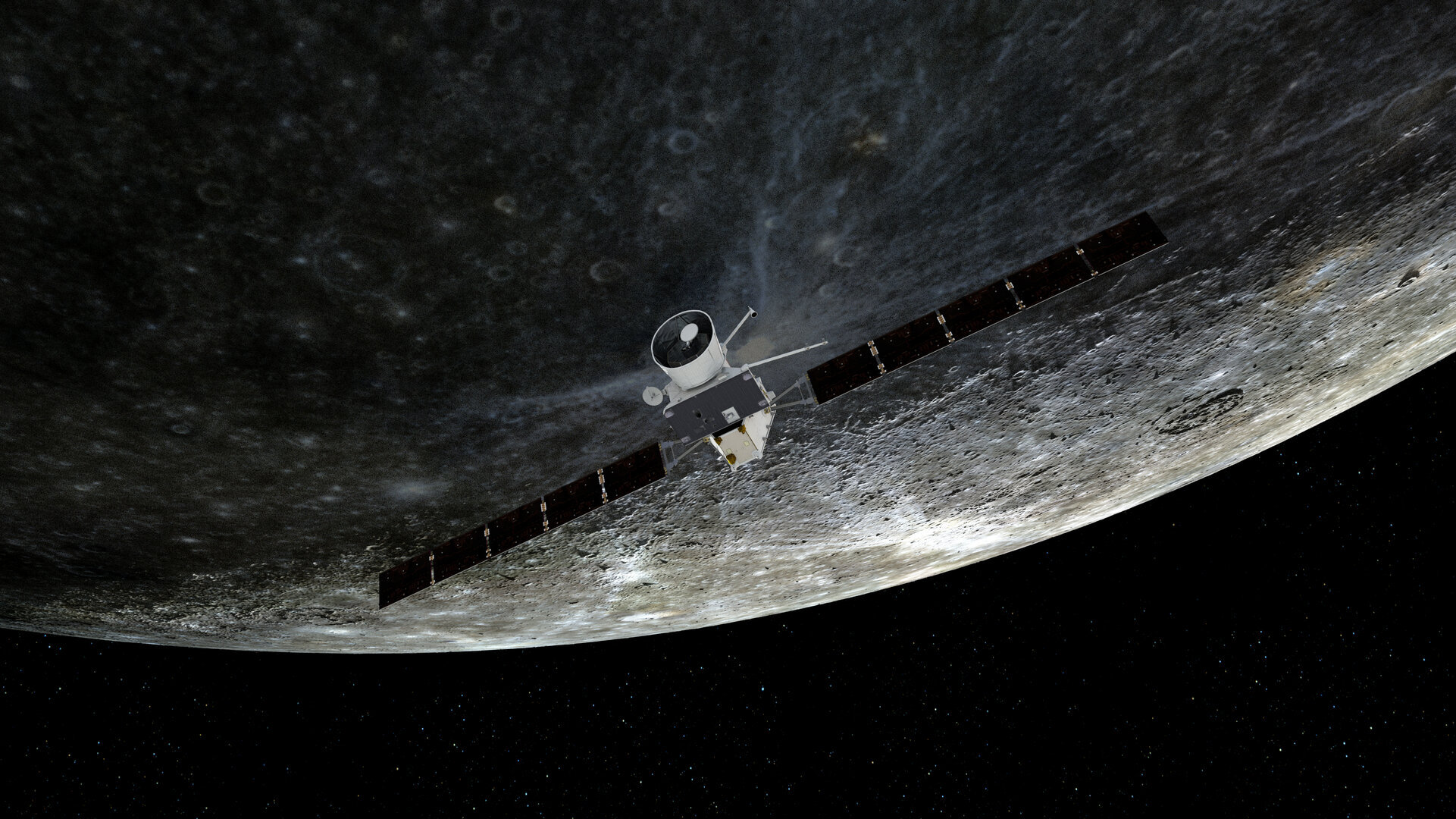

A unique aspect of the BepiColombo mission is its dual spacecraft nature. The ESA-led Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the JAXA-led Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, Mio, will be delivered into complementary orbits around the planet by a third module, ESA’s Mercury Transfer Module, in 2025. Working together, they will study all aspects of this mysterious inner planet from its core to surface processes, magnetic field and exosphere, to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its parent star. Dual observations are key to understanding solar wind-driven magnetospheric processes, and BepiColombo will break new ground by providing unparalleled observations of the planet’s magnetic field and the interaction of the solar wind with the planet at two different locations at the same time.

On course for slingshot

Gravitational flybys require extremely precise deep-space navigation work, ensuring that a spacecraft passes the massive body that will alter its orbit at just the right distance, from the correct angle and with the right velocity. All of this is calculated years in advance but has to be as close to perfect as possible on the day.

Getting into orbit around Mercury is a challenging task. First BepiColombo had to shed the orbital energy it was ‘born’ with as it launched from Earth, which meant it first flew in a similar orbit to our home planet – and shrinking its orbit down to a size more similar to Mercury’s. BepiColombo’s first flybys of Earth and Venus were thus used to ‘dump’ energy and fall closer to the centre of the Solar System, while the series of Mercury flybys are being used to lose more orbital energy, but now with the purpose of being captured by the scorched planet.

Access the video

For this second of six such flybys, BepiColombo needs to pass Mercury at a distance of just 200 km from its surface, with a relative speed of 7.5 km/s. In doing so, BepiColombo’s velocity in relation to the Sun will be slowed by 1.3 km/s, bringing it closer towards Mercurial orbit.

“We have three slots available to perform correction manoeuvres from ESA’s ESOC Mission Control in Darmstadt, Germany, in order to be in precisely the right place at the right time to use Mercury’s gravity as we need it,” explains Elsa Montagnon, Mission Manager for BepiColombo.

“The first such slot was used to tune the desired flyby altitude of 200 km over the planet's surface, ensuring the spacecraft would not be on a collision course with Mercury. Thanks to the meticulous work of our Flight Dynamics colleagues, this first trajectory correction executed very accurately such that further slots were not needed.”

Selfie-cam is go

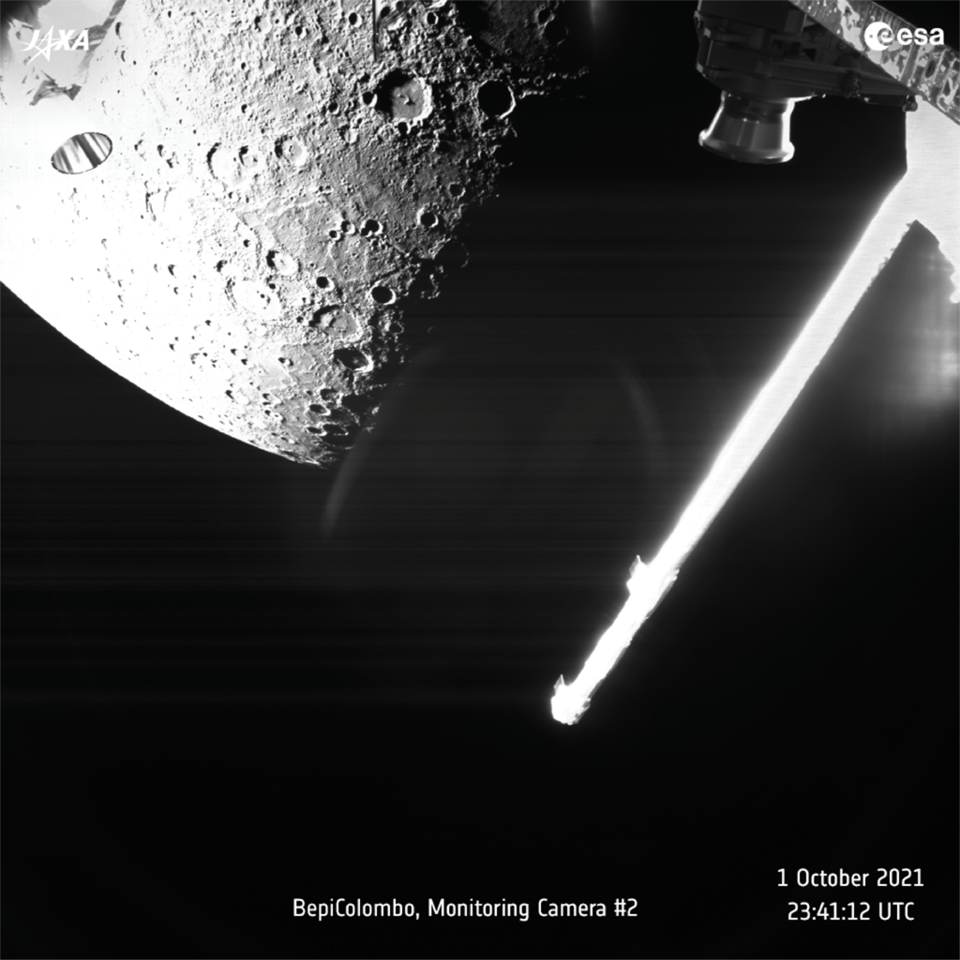

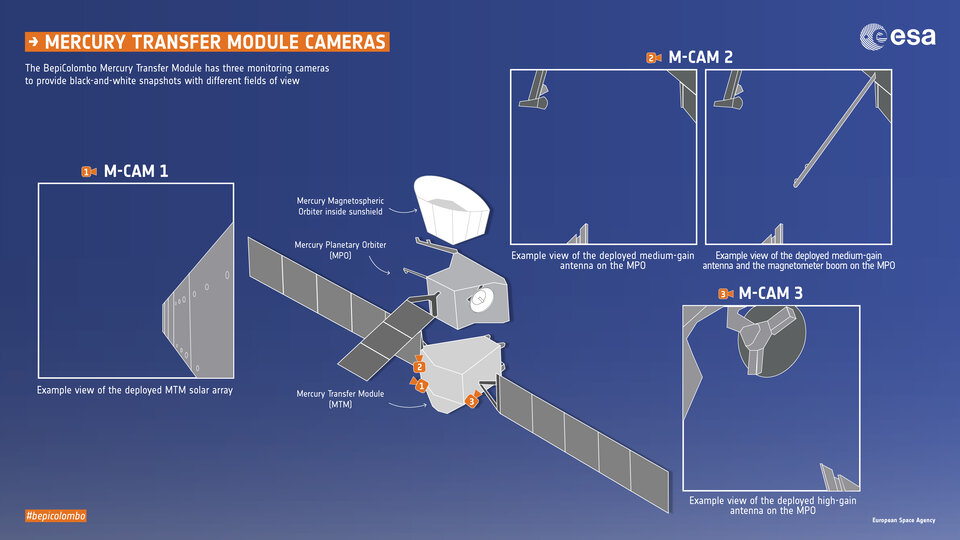

During the flybys it is not possible to take high-resolution imagery with the main science camera because it is shielded by the transfer module while the spacecraft is in cruise configuration. However, BepiColombo’s three monitoring cameras (MCAMs) will be taking photos.

Because BepiColombo’s closest approach will be on the planet’s nightside, the first images in which Mercury will be illuminated are expected to be at around five minutes after close approach, at a distance of about 800 km.

The cameras provide black-and-white snapshots in 1024 x 1024 pixel resolution, and are positioned on the Mercury Transfer Module such that they also capture the spacecraft’s solar arrays and antennas. As the spacecraft changes its orientation during the flyby, Mercury will be seen passing behind the spacecraft structural elements.

The first images will be downlinked within a couple of hours after closest approach; the first is expected to be available for public release during the afternoon of 23 June. Subsequent images will be downlinked throughout the remainder of the day and a second image release, comprising multiple new images, is expected by Friday morning. All images are scheduled to be released to the public in the Planetary Science Archive on Monday 27 June.

For the closest images it should be possible to identify large impact craters and other prominent geological features linked to tectonic and volcanic activity such as scarps, wrinkle ridges and lava plains on the planet’s surface. Mercury’s heavily cratered surface records a 4.6 billion year history of asteroid and comet bombardment, which together with unique tectonic and volcanic curiosities will help scientists unlock the secrets of the planet’s place in Solar System evolution.

Follow the flyby

Follow @Esaoperations and @bepicolombo together with @ESA_Bepi, @ESA_MTM and @JAXA_MMO for updates.

Quelle: ESA

----

Update: 25.06.2022

.

Second helpings of Mercury

The ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission has made its second gravity assist of planet Mercury, capturing new close-up images as it steers closer towards Mercury orbit in 2025.

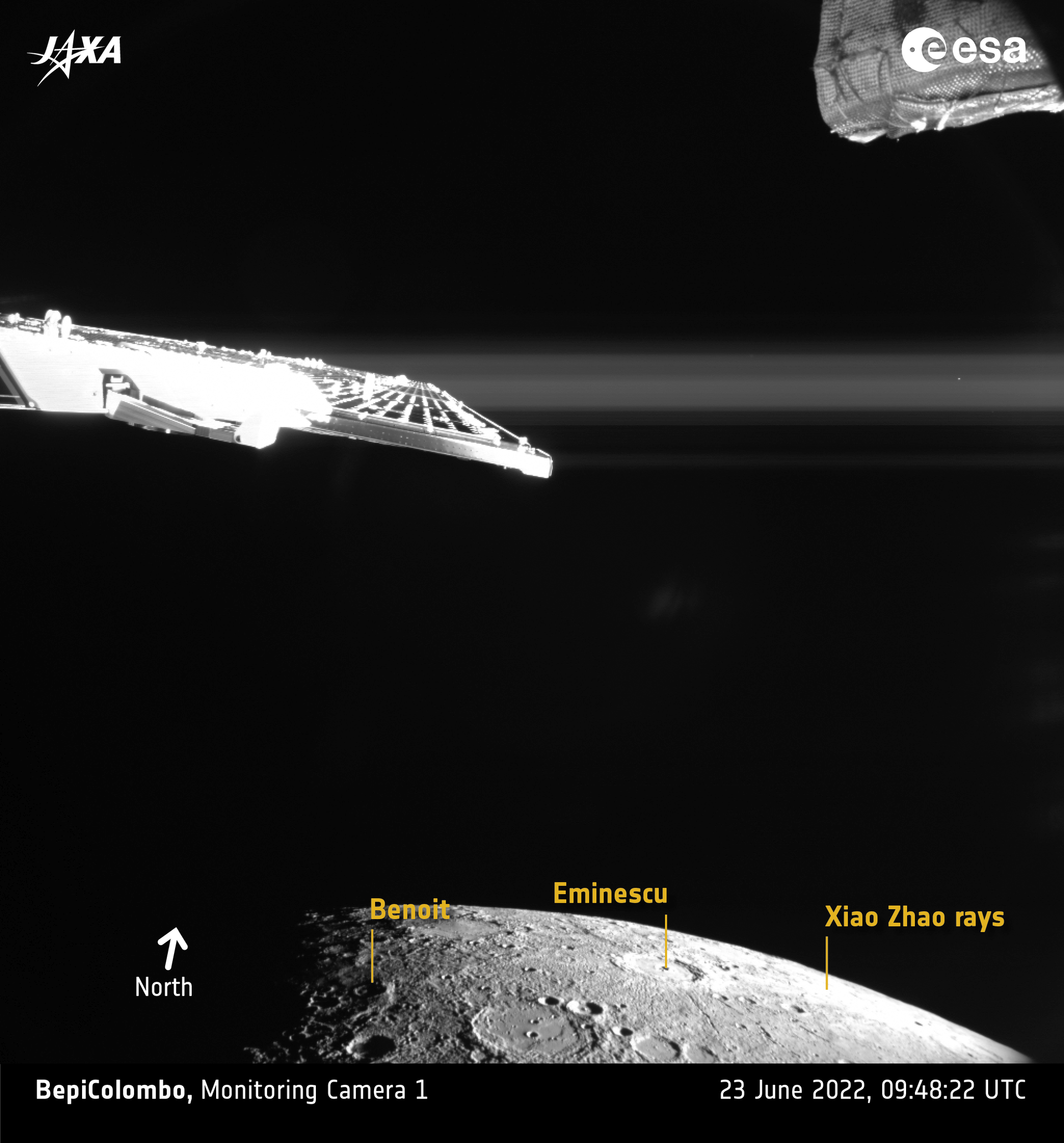

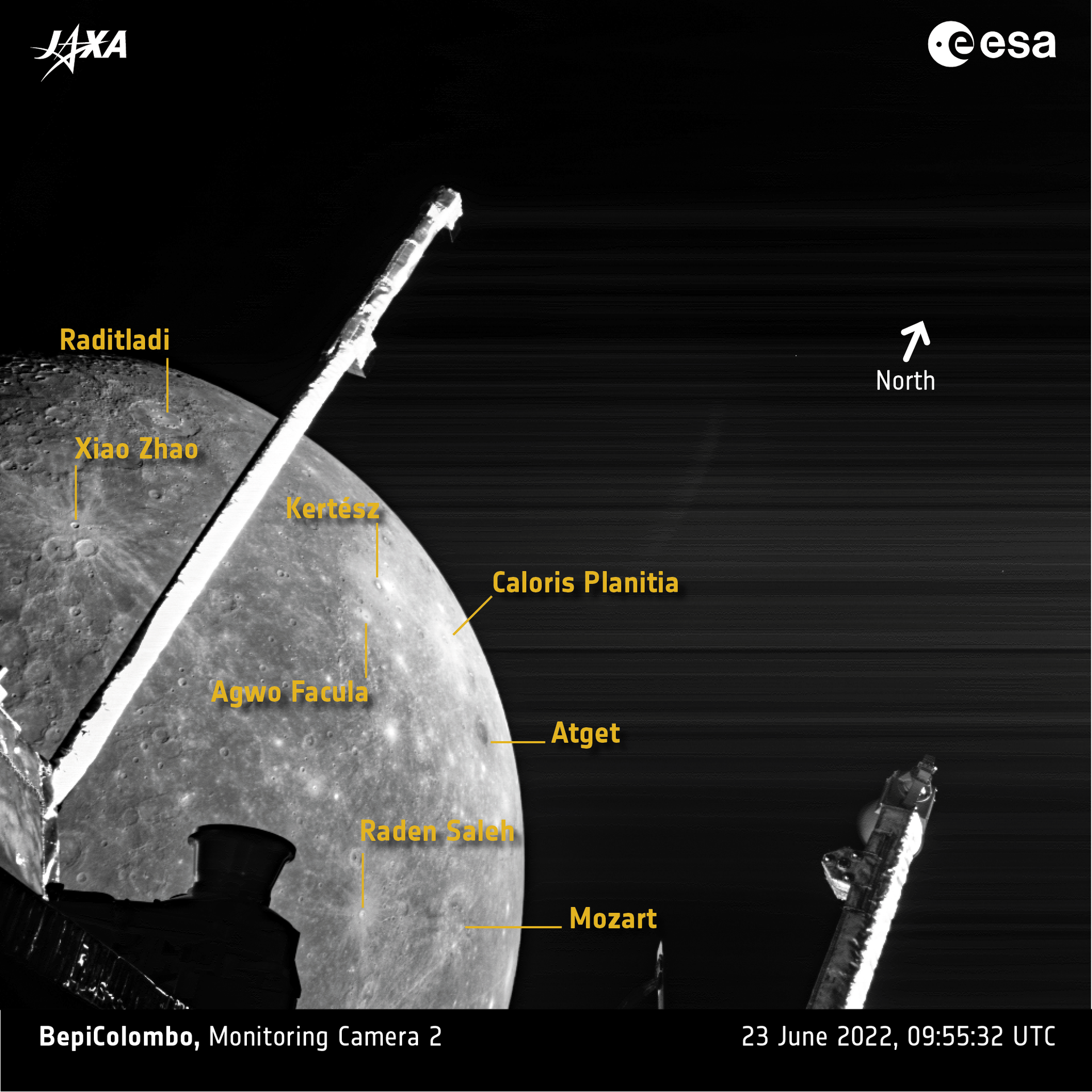

The closest approach took place at 09:44 UTC (11:44 CEST) on 23 June 2022, about 200 km above the planet’s surface. Images from the spacecraft’s three monitoring cameras (MCAM), along with scientific data from a number of instruments, were collected during the encounter. The MCAM images, which provide black-and-white snapshots in 1024 x 1024 pixel resolution, were downloaded over the course of yesterday afternoon, and a selection is presented here (click images to expand captions for more details).

“We have completed our second of six Mercury flybys and will be back this time next year for our third before arriving in Mercury orbit in 2025,” says Emanuela Bordoni, ESA’s BepiColombo Deputy Spacecraft Operations Manager.

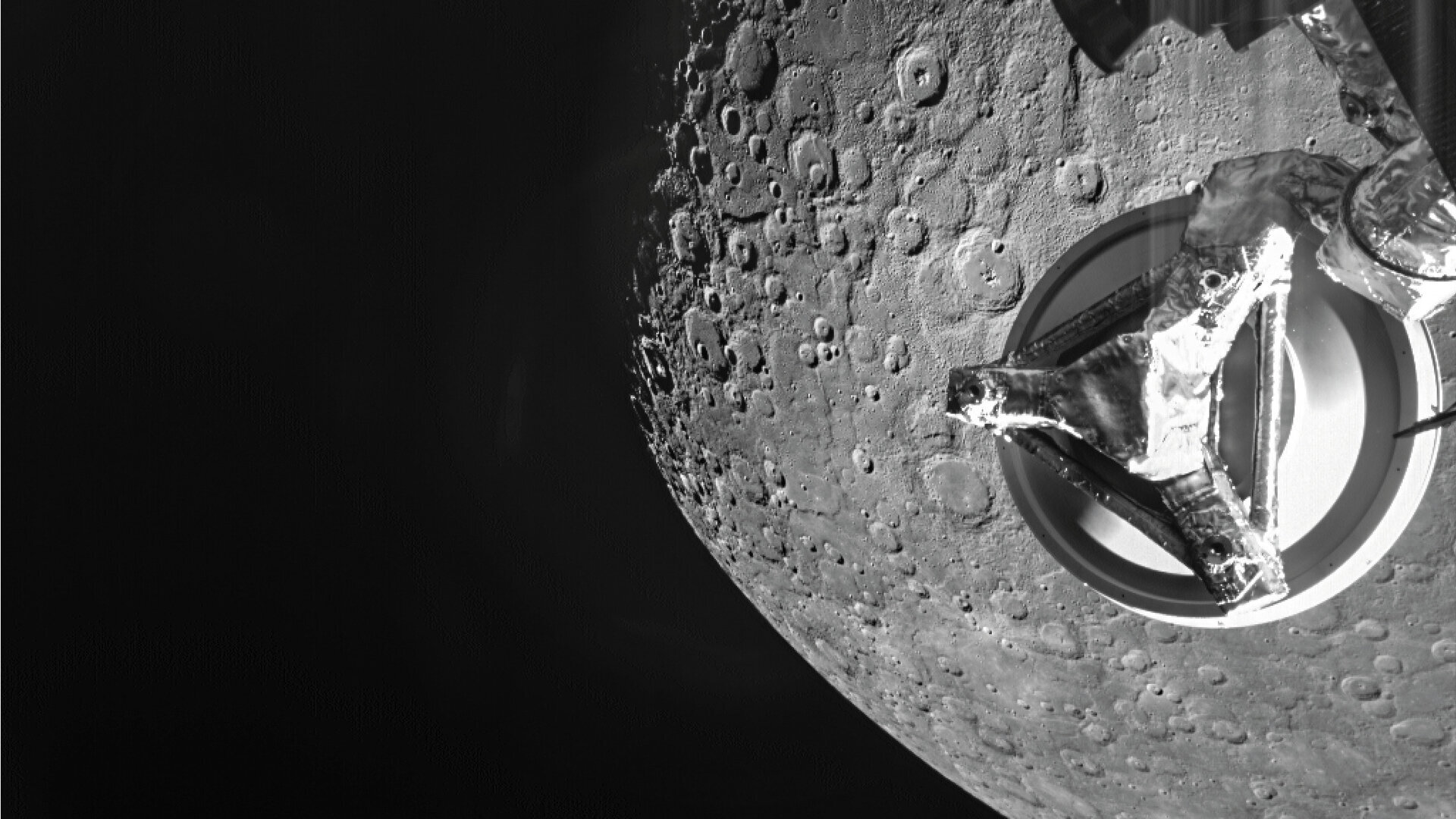

Because BepiColombo’s closest approach was on the planet’s nightside, the first images in which Mercury is illuminated were taken at around five minutes after close approach, at a distance of about 800 km. Images were taken for about 40 minutes after the close approach as the spacecraft moved away from the planet again.

As BepiColombo flew from the nightside to dayside, the Sun seemingly rose over the cratered surface of the planet, casting shadows along the terminator – the boundary between night and day – and highlighting the topography of the terrain in dramatic fashion.

Jack Wright, a member of the MCAM team, and a research fellow based at ESA’s European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC) in Madrid, helped to plan the imaging sequence for the flyby. He said: “I punched the air when the first images came down, and I only got more and more excited after that. The images show beautiful details of Mercury, including one of my favourite craters, Heaney, for which I suggested the name a few years ago.”

Heaney is a 125 km wide crater covered in smooth volcanic plains. It hosts a rare example of a candidate volcano on Mercury, which will be an important target for BepiColombo’s high resolution imaging suite once in orbit.

Just a few minutes after closest approach and with the Sun shining from above, Mercury’s largest impact feature, the 1550 km-wide Caloris basin swung into view for the first time, its highly-reflective lavas on its floor making it stand out against the darker background. The volcanic lavas in and around Caloris are thought to post-date the formation of the basin itself by a hundred million years or so, and measuring and understanding the compositional differences between these is an important goal for BepiColombo.

“Mercury flyby 1 images were good, but flyby 2 images are even better,” commented David Rothery of the Open University who leads ESA’s Mercury Surface & Composition Working Group and who is also a member of the MCAM team. “The images highlight many of the science goals that we can address when BepiColombo gets into orbit. I want to understand the volcanic and tectonic history of this amazing planet.”

BepiColombo will build on the data collected by NASA’s Messenger mission that orbited Mercury 2011-2015. BepiColombo’s two science orbiters – ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter – will operate from complementary orbits to study all aspects of mysterious Mercury from its core to surface processes, magnetic field and exosphere, to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its parent star.

Even though BepiColombo is currently in ‘stacked’ cruise configuration, meaning many instruments cannot be fully operated during the brief flybys, they can still grab insights into the magnetic, plasma and particle environment around the spacecraft, from locations not normally accessible during an orbital mission.

“Our instrument teams on both spacecraft have started receiving their science data and we’re looking forward to sharing our first insights from this flyby,” says Johannes Benkhoff, ESA’s BepiColombo project scientist. “It will be interesting to compare the data with what we collected on our first flyby, and add to this unique dataset as we build towards our main mission.”

BepiColombo’s main science mission will begin in early 2026. It is making use of nine planetary flybys in total: one at Earth, two at Venus, and six at Mercury, together with the spacecraft’s solar electric propulsion system, to help steer into Mercury orbit. Its next Mercury flyby will take place on 20 June 2023.

For more information, please contact:

ESA media relations

media@esa.int

All MCAM images will be publicly available in the Planetary Science Archive next week. Impressions from the science instruments will be reported in the coming weeks. Follow @bepicolombo on Twitter for further updates.

An image gallery with annotated and non-annotated versions of the images released yesterday and today is provided below: