.

Mariner IV on the launch pad under its streamlined metal launch shroud at Cape Kennedy, November 1964. Mariner III would have appeared very similar. Image: NASA

.

Launch of Mariner III, the first of two identical spacecraft NASA planned to dispatch to Mars in November 1964, was only 12 days away when Norman Haynes and Harold Gordon of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, completed a brief internal memorandum titled “A Study of the Probability of Depositing Viable Organisms on Mars During the Mariner 1964 Mission.” It was among the first U.S. documents to look at the practicalities of what would later come to be called “planetary protection.”

A few weeks prior to the Haynes and Gordon memorandum, the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) of the International Council of Scientific Unions had called upon the United States and the Soviet Union to reduce the probability of accidental impact on Mars by unsterilized flyby or orbiter spacecraft to three chances in 100,000. NASA policy in 1964 allowed one chance in 10,000 of accidental impact.

Haynes and Gordon looked at the Mariner Mars 1964 mission profile, which included up to three propulsive maneuvers (injection onto an Earth-Mars transfer trajectory followed by one or two course-correction burns), then computed the probability that these maneuvers might cause Mariner III or Mariner IV to collide with Mars. They determined that the probability of impact was six chances in 100,000, and maintained that this could not be reduced in time for the twin Mariner launches.

They then computed the probability that terrestrial microbes expelled through course-correction motor firings, spacecraft outgassing, and attitude control jet operation might fall on Mars. Their memo discounted the first two sources because they would expel microbes early in the mission when Mariner III and Mariner IV were far from Mars. Because of this, solar ultraviolet radiation would kill most expelled microbes long before they could reach the planet. The course-correction motor’s hot exhaust would kill almost all microorganisms it expelled and would push any survivors away from Mars. In addition, a high surface-to-mass ratio meant that microbes would be highly susceptible to the minute pressure exerted by sunlight, so would be pushed far from the planet.

The third source, attitude-control jets, was more worrisome, Haynes and Gordon judged, because they might operate while the twin Mariners were near Mars. The nitrogen gas expelled from the jets would be filtered but not sterilized before it was put on board the spacecraft, so it might include up to one million microbes. Haynes and Gordon noted that the twin Mariner Mars 1964 spacecraft would each carry four small solar vanes to take advantage of solar radiation pressure, thus trimming nitrogen use. Even so, they placed the probability that a microbe from the jets would reach Mars as high as one chance in 1000.

Mariner III lifted off from Launch Complex 13 at Cape Kennedy, Florida, on 5 November 1964, atop an Atlas-Agena D rocket. The streamlined launch shroud covering the spacecraft failed to separate after Mariner III reached space, preventing its solar arrays from deploying. Controllers lost radio contact with the spacecraft on 6 November as its batteries ran out. An investigation revealed that the shroud’s fiberglass inner layer had probably separated from its metal outer layer and become tangled on the spacecraft. Mariner III was not on course for Mars when it failed, so it did not strike the planet.

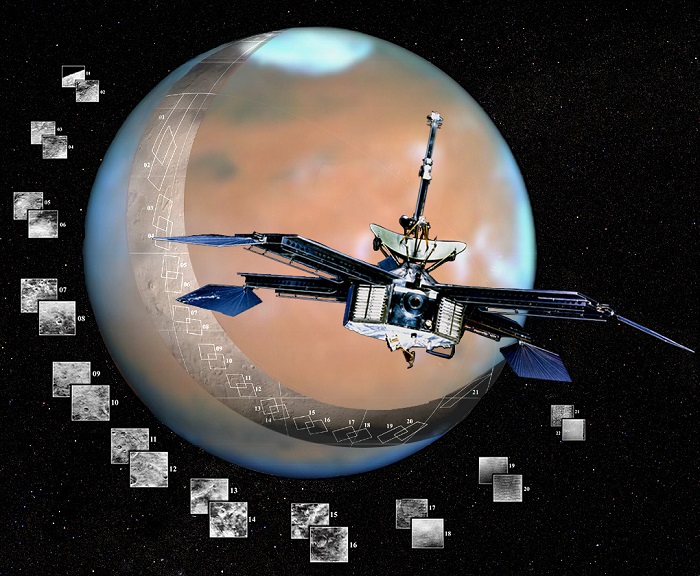

Engineers quickly replaced Mariner IV’s launch shroud with one lacking the troublesome fiberglass layer. The spacecraft lifted off from Launch Complex 12 on 28 November and performed a course-correction maneuver on 5 December, after which it was on course for its Mars flyby. After a largely uneventful flight, Mariner IV flew past Mars on 15 July 1965, at a distance of about 9850 kilometers. The spacecraft captured 21 images of the planet’s surprisingly cold, cratered surface, and its radio refraction experiment indicated an atmospheric pressure roughly 10 times less than predicted, or only about 1% as great as Earth’s.

Mariner IV, Mars as viewed from Earth, and the strip of images the spacecraft captured as it flew past the planet on 15 July 1965. The Mariner IV spacecraft was identical to its ill-starred predecessor, Mariner III. Solar sail vanes, colored blue, are visible at the ends of the four solar panels. Image: NASA

Quelle: WIRED