2.05.2022

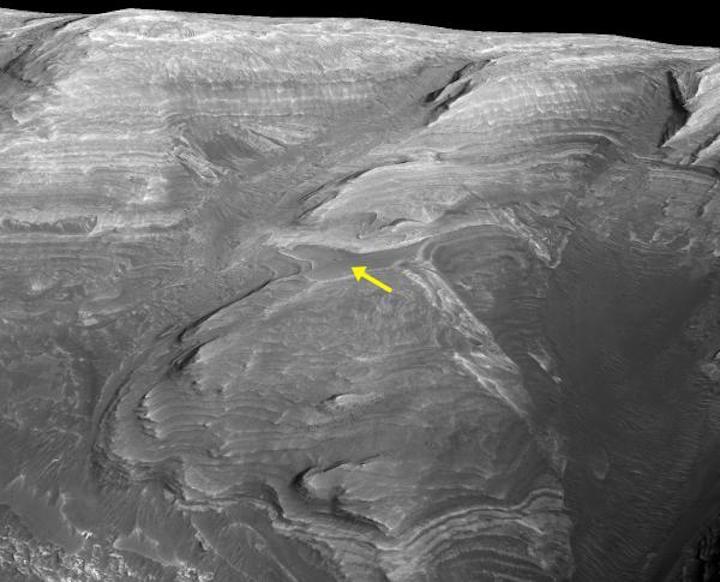

The marker horizon (yellow arrow) is darker, smoother, and harder than the sulfate-bearing rocks surrounding it. HiRISE image merged to a Digital Terrain Model (DTM) perspective view showing approximately 1 kilometer of topography across Mount Sharp. Image features three times vertical exaggeration.

Credit: NASA/University of Arizona.

Scientists have been studying the sediments within Mars’ Gale crater for many years using orbital data sets, but thanks to the Curiosity rover driving across these deposits we can also obtain up-close observations and detailed measurements of the rocks, similar to field work done by geologists on Earth.

A new paper led by Planetary Science Institute Senior Scientist Catherine Weitz takes a new look at an enigmatic feature seen in orbital data of Mount Sharp, a 5.5-kilometer-high mound in Gale crater: a darker, stronger, flatter, smooth rock layer or weathering horizon that stands out from the sulfate-bearing rocks in which it occurs. Because the darker horizon can be distinguished in orbital data from the surrounding brighter sulfate-bearing rocks, it can be traced across much of Mount Sharp and it marks a specific time period within the crater, which is why it is referred to as a “marker horizon.”

The marker horizon appears to be either one or more rock layers or a zone of weathering with a different appearance from the sulfate-bearing rocks in which it occurs. Marker horizons are found on Earth too, with volcanic ash being a common marker horizon because it can appear different from the surrounding sediments and it can be traced across variable landscapes. Geologists can use marker horizons as time-stratigraphic features, meaning that the marker horizon formed during a single event or a specific time period, so by tracing the marker horizon across large areas we can always know what rocks were deposited either before or after it in stratigraphy.

“Some event occurred within Gale crater during the deposition of sulfate-bearing sediments that resulted in a different kind of rock unit. The marker horizon is distinct in appearance from the sulfate-bearing rocks above and below it, indicating an environmental change occurred for a brief time, such as a drier period, or perhaps a regional event like an explosive eruption from a nearby volcano that deposited ash across a large area which included Gale crater,” Weitz said.

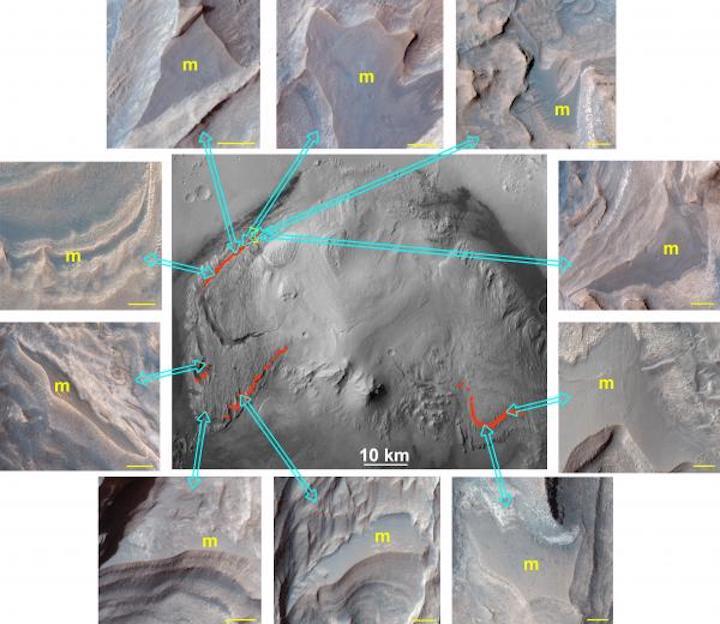

“We used orbital data collected from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), Context Camera (CTX), and Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instruments on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) to map out where this marker horizon occurs throughout Mount Sharp and study its appearance and composition. We found that the marker horizon varies in its elevation by 1.6 kilometers across Mount Sharp, that it dips between 1 and 5 degrees away from the center of Gale crater, and it has a mafic composition similar to other basaltic materials including aeolian sands,” said Weitz, lead author of “Orbital Observations of a Marker Horizon at Gale Crater” that appears in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

“We explored several different formation mechanisms for the marker horizon. It could be composed of the same materials as the sulfate-bearing rocks above and below it, but became harder and more resistant to erosion either during formation or subsequently by water carrying minerals to cement it. The marker horizon could also be a sandstone or lag deposit that formed when it was drier in Gale crater relative to when the sulfates formed. Another possibility is that the horizon contains volcanic ash that was deposited when a nearby volcano explosively erupted ash into the Martian atmosphere that later became hardened. All of these potential origins require the presence of at least some water to cause cementation that hardened the horizon,” Weitz said. “Our orbital observations currently favor an indurated sulfate or volcanic ash origin, but we will have to wait until the Curiosity rover reaches the horizon in the coming months before determining which origin is most plausible.”

Closer observations will allow scientists to better understand why the marker horizon appears so different from the nearby sulfate outcrops. “We are fortunate that the Curiosity rover is planning to reach the marker horizon in the coming months as it traverses up Mount Sharp through the sulfate-bearing rocks, providing valuable ground measurements that can be used to evaluate the different origin scenarios. Currently the Curiosity rover is approximately 700 meters away from the marker horizon, crossing from the Greenheugh pediment to the clay-sulfate transition region. Exploration of the marker horizon by Curiosity will enable detailed analyses of sedimentological properties, including grain sizes, any unconformities, internal structures, textures, and chemical composition,” said Weitz, a Co-Investigator on the HiRISE camera and a science team member on the Curiosity rover.

“These in situ observations and measurements that Curiosity can make are critical to distinguish between the multiple proposed formation scenarios. Of course, Mars can throw us a curveball and it may turn out that the origin of the marker horizon could be the result of something we did not anticipate from the orbital data sets,” Weitz said. “Only when Curiosity begins its own investigation of the marker horizon will the data be sufficient to hopefully unravel the origin of this enigmatic marker horizon and help us further understand the intriguing sedimentary history of Gale crater.”

Weitz’s work on the project was funded by a grant to PSI from NASA’s Mars Data Analysis program, grant 80NSSC19K1222.

Context Camera (CTX) mosaic of Mount Sharp (center) in Gale Crater with exposures of the marker horizon shown in red. Surrounding the CTX mosaic are HiRISE enhanced color image subsets of the marker horizon (m) taken throughout Mount Sharp, with blue arrows showing approximate locations where each subset occurs in Mount Sharp. The yellow scale bar in each subset image is 50 meters. A different stretch has been applied to each subset image so the colors are not comparable between images.

Credit: NASA/MSSS/University of Arizona.

Quelle: PSI